Cornwall Farmsteads Character Statement Cornwall Farmsteads Character Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old Vicarage Crosstown • Morwenstow • Bude • Ex23 9Rs

THE OLD VICARAGE CROSSTOWN • MORWENSTOW • BUDE • EX23 9RS THE OLD VICARAGE CROSSTOWN • MORWENSTOW • BUDE • EX23 9RS DISTANCES Bude town centre about 8 miles. Holsworthy about 16 miles. Bodmin Parkway station about 39 miles. Cornwall Airport (Newquay) about 47 miles. M5 junction 31, about 59 miles. An elegant Victorian vicarage, built in the English Romantic style by the Reverend R.S. Hawker, a towering figure of 19th c. Cornish cultural history. Unique example of the romantic style, in a stunning setting Nestles in own valley facing the Atlantic Ocean Six bedrooms, three with en suite Four reception rooms Front and rear staircases Billiards room Large rooms, full of natural light, with numerous original features Stable converted to three bedroomed cottage Surrounded by own gardens and adjoining the grounds of Morwenstow Church Holy well in orchard SAVILLS TRURO 73 Lemon Street, Truro, Cornwall TR1 2PN 01872 243 200 [email protected] Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text LOCATION composed The Song of the Western Men, better known as Morwenstow, Cornwall’s northernmost parish, is one of Trelawny, still sung with great enthusiasm in the county. His rolling pasture, deep valleys and majestic cliffs. The Atlantic life as a compassionate, reforming vicar in the parish is well documented and worthy of further reading. Ocean beats relentlessly at the coastline. Yet, tucked into its own tree-lined valley is the Old Vicarage, sheltered and Within the hamlet comprising the church and Old Vicarage, unseen from any road until one rounds the corner from there is the popular Bush Inn, the Rectory tea rooms and Morwenstow Church and descends the private drive. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Farmsteads Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Thesaurus for indexing different types of farmsteads, related buildings, areas and layouts. Date: February 2020 AGRICULTURAL COMPLEXES AND BUILDINGS CLASS LIST AGRICULTURAL BUILDING ANIMAL HOUSING CATTLE HOUSING COW HOUSE HEMMEL LINHAY LOOSE BOX OX HOUSE SHELTER SHED PIG HOUSING LOOSE BOX PIGSTY POULTIGGERY POULTRY HOUSING GOOSE HOUSE HEN HOUSE LOOSE BOX POULTIGGERY RAMS PEN SHEEP HOUSE HOGG HOUSE LOOSE BOX STABLING STABLE BARN AISLED BARN BANK BARN COMBINATION BARN DUTCH BARN FIELD BARN HAY BARN STADDLE BARN THRESHING BARN BASTLE BASTLE (DEFENSIVE) BASTLE (NON DEFENSIVE) BOILING HOUSE CHAFF HOUSE CIDER HOUSE DAIRY DOVECOTE FARMHOUSE GRANARY HORSE ENGINE HOUSE KILN CORN DRYING KILN HOP KILN LAITHE HOUSE LONGHOUSE MALTINGS MILL MIXING HOUSE ROOT AND FODDER STORE SHED 2 AGRICULTURAL COMPLEXES AND BUILDINGS CLASS LIST CART SHED PORTAL FRAMED SHED SHELTER SHED SILAGE CLAMP SILAGE TOWER TOWER HOUSE WELL HOUSE WORKERS HOUSE AGRICULTURAL COMPLEX CROFT FARMSTEAD GRANGE MANORIAL FARM VACCARY FIELD BARN OUTFARM SHIELING SMALLHOLDING YARD CATTLE YARD COVERED YARD HORSE YARD SHEEP YARD STACK YARD 3 PLAN TYPES CLASS LIST COURTYARD PLAN LOOSE COURTYARD PLAN LOOSE COURTYARD (FOUR SIDED) LOOSE COURTYARD (ONE SIDED) LOOSE COURTYARD (THREE SIDED) LOOSE COURTYARD (TWO SIDED) REGULAR COURTYARD PLAN REGULAR COURTYARD E PLAN REGULAR COURTYARD F PLAN REGULAR COURTYARD FULL PLAN REGULAR COURTYARD H PLAN REGULAR COURTYARD L PLAN REGULAR COURTYARD MULTI YARD REGULAR COURTYARD T PLAN REGULAR COURTYARD U PLAN REGULAR COURTYARD Z PLAN DISPERSED PLAN DISPERSED CLUSTER PLAN DISPERSED DRIFTWAY PLAN DISPERSED MULTI YARD PLAN L PLAN (HOUSE ATTACHED) LINEAR PLAN PARALLEL PLAN ROW PLAN 4. -

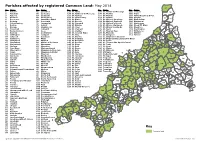

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

Copyrighted Material

176 Exchange (Penzance), Rail Ale Trail, 114 43, 49 Seven Stones pub (St Index Falmouth Art Gallery, Martin’s), 168 Index 101–102 Skinner’s Brewery A Foundry Gallery (Truro), 138 Abbey Gardens (Tresco), 167 (St Ives), 48 Barton Farm Museum Accommodations, 7, 167 Gallery Tresco (New (Lostwithiel), 149 in Bodmin, 95 Gimsby), 167 Beaches, 66–71, 159, 160, on Bryher, 168 Goldfish (Penzance), 49 164, 166, 167 in Bude, 98–99 Great Atlantic Gallery Beacon Farm, 81 in Falmouth, 102, 103 (St Just), 45 Beady Pool (St Agnes), 168 in Fowey, 106, 107 Hayle Gallery, 48 Bedruthan Steps, 15, 122 helpful websites, 25 Leach Pottery, 47, 49 Betjeman, Sir John, 77, 109, in Launceston, 110–111 Little Picture Gallery 118, 147 in Looe, 115 (Mousehole), 43 Bicycling, 74–75 in Lostwithiel, 119 Market House Gallery Camel Trail, 3, 15, 74, in Newquay, 122–123 (Marazion), 48 84–85, 93, 94, 126 in Padstow, 126 Newlyn Art Gallery, Cardinham Woods in Penzance, 130–131 43, 49 (Bodmin), 94 in St Ives, 135–136 Out of the Blue (Maraz- Clay Trails, 75 self-catering, 25 ion), 48 Coast-to-Coast Trail, in Truro, 139–140 Over the Moon Gallery 86–87, 138 Active-8 (Liskeard), 90 (St Just), 45 Cornish Way, 75 Airports, 165, 173 Pendeen Pottery & Gal- Mineral Tramways Amusement parks, 36–37 lery (Pendeen), 46 Coast-to-Coast, 74 Ancient Cornwall, 50–55 Penlee House Gallery & National Cycle Route, 75 Animal parks and Museum (Penzance), rentals, 75, 85, 87, sanctuaries 11, 43, 49, 129 165, 173 Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Round House & Capstan tours, 84–87 113 Gallery (Sennen Cove, Birding, -

Family History #3

HOP PICKING IN OUR FAMILY HISTORY HOP PICKING LIFE It is impossible for us to really understand the interlude that hop picking had in the life of Londoners. It wasn’t an easy life and as the prices for hops fell in the 1950’s, the pay was low. But, good or bad, thousands regularly left their homes in London for the Kent hop fields. A holiday? A change of scenery? A chance to earn a few extra pennies? The opportunity for the children to enjoy fresh air and green grass? The reasons are as many and varied as the people who went. HOPPER HUT Accommodation in the hopper huts was basic even for the East Enders. I have no doubt if they were asked they would have replied that, “A change is as good as a ‘oliday!” The first job for the transplanted Londoners was to fill large sacking with straw for mattresses. Toilets were outside and bathing was of the tin tub variety {this may not have been so different from what they left behind) Most huts were made out of corrugated iron which meant cold nights and hot days. Mum said that some women took a few “specials” with them to make it more like home. A little bit of wallpaper, left over curtain material provided them with the illusion of home comforts. THE HOPPER SPECIAL For the thousands of East Enders who made the annual pilgrimage the choices of how to get there was either in a special train or open backed army trucks. The necessities of life needed for the Kent hop fields were packed into old prams and boxes or stuffed into the back of trucks with a child sitting on each as a mark of ownership. -

Like a Ton of Bricks Here’S a Ton of 7-Letter Bingos About BUILDINGS, STRUCTURES, COMPONENTS Compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club

Like a Ton of Bricks Here’s a ton of 7-letter bingos about BUILDINGS, STRUCTURES, COMPONENTS compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club A 7s ABATTIS AABISTT abatis (barrier made of felled trees) [n -ES] ACADEME AACDEEM place of instruction [n -S] ACADEMY AACDEMY secondary school [n -MIES] AGOROTH AGHOORT AGORA, marketplace in ancient Greece [n] AIRPARK AAIKPRR small airport (tract of land maintained for landing and takeoff of aircraft) [n -S] AIRPORT AIOPRRT tract of land maintained for landing and takeoff of aircraft [n -S] ALAMEDA AAADELM shaded walkway [n -S] ALCAZAR AAACLRZ Spanish fortress or palace [n -S] ALCOVES ACELOSV ALCOVE, recessed section of room [n] ALMEMAR AAELMMR bema (platform in synagogue) [n -S] ALMONRY ALMNORY place where alms are distributed [n -RIES] AMBONES ABEMNOS AMBO, pulpit in early Christian church [n] AMBRIES ABEIMRS AMBRY, recess in church wall for sacred vessels [n] ANDIRON ADINNOR metal support for holding wood in fireplace [n -S] ANNEXED ADEENNX ANNEX, to add or attach [v] ANNEXES AEENNSX ANNEXE, something added or attached [n] ANTEFIX AEFINTX upright ornament at eaves of tiled roof [n -ES, -, -AE] ANTENNA AAENNNT metallic device for sending or receiving radio waves [n -S, -E] ANTHILL AHILLNT mound formed by ants in building their nest [n -S] APSIDAL AADILPS APSE, domed, semicircular projection of building [adj] APSIDES ADEIPSS APSIS, apse (domed, semicircular projection of building) [n] ARBOURS ABORRSU ARBOUR, shady garden shelter [n] ARCADED AACDDER ARCADE, to provide arcade (series of arches) -

The Post-Medieval Rural Landscape, C AD 1500–2000 by Anne Dodd and Trevor Rowley

THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000–2000 The Post-Medieval Rural Landscape AD 1500–2000 THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 The post-medieval rural landscape, c AD 1500–2000 By Anne Dodd and Trevor Rowley INTRODUCTION Compared with previous periods, the study of the post-medieval rural landscape of the Thames Valley has received relatively little attention from archaeologists. Despite the increasing level of fieldwork and excavation across the region, there has been comparatively little synthesis, and the discourse remains tied to historical sources dominated by the Victoria County History series, the Agrarian History of England and Wales volumes, and more recently by the Historic County Atlases (see below). Nonetheless, the Thames Valley has a rich and distinctive regional character that developed tremendously from 1500 onwards. This chapter delves into these past 500 years to review the evidence for settlement and farming. It focusses on how the dominant medieval pattern of villages and open-field agriculture continued initially from the medieval period, through the dramatic changes brought about by Parliamentary enclosure and the Agricultural Revolution, and into the 20th century which witnessed new pressures from expanding urban centres, infrastructure and technology. THE PERIOD 1500–1650 by Anne Dodd Farmers As we have seen above, the late medieval period was one of adjustment to a new reality. -

Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

© 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY 41–42 HENDHYSCANS KERNOW 2002–3 EDITORS GRAEME KIRKHAM AND PETER HERRING (Published 2006) CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © COPYRIGHT CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2006 No part of this volume may be reproduced without permission of the Society and the relevant author ISSN 0070 024X Typesetting, printing and binding by Arrowsmith, Bristol © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Contents Preface i HENRIETTA QUINNELL Reflections iii CHARLES THOMAS An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly 1 CHARLES JOHNS Excavation of an Early Christian cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow 80 PRU MANNING and PETER STEAD Journeys to the Rock: archaeological investigations at Tregarrick Farm, Roche 107 DICK COLE and ANDY M JONES Chariots of fire: symbols and motifs on recent Iron Age metalwork finds in Cornwall 144 ANNA TYACKE Cornwall Archaeological Society – Devon Archaeological Society joint symposium 2003: 149 archaeology and the media PETER GATHERCOLE, JANE STANLEY and NICHOLAS THOMAS A medieval cross from Lidwell, Stoke Climsland 161 SAM TURNER Recent work by the Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 165 Recent work in Cornwall by Exeter Archaeology 194 Obituary: R D Penhallurick 198 CHARLES THOMAS © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Preface This double-volume of Cornish Archaeology marks the start of its fifth decade of publication. Your Editors and General Committee considered this milestone an appropriate point to review its presentation and initiate some changes to the style which has served us so well for the last four decades. The genesis of this style, with its hallmark yellow card cover, is described on a following page by our founding Editor, Professor Charles Thomas. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

Institute of 1K Hydrology • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• Instituteof 1k Hydrology • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Natural Environment Research Council • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • DERIVATION OF THEORETICAL FLOWS FOR THE COLLIFORD RESERVOIR MODEL (A report of contract work to South West Water Services Ltd under IH project T05056V1) J.R. BLACKIE, C HUGHES and T.KM. SIMPSON Institute of Hydrology • Maclean Building Crowmarsh Gifford Wallingford Oxon OXIO 8138 UK Tel: 0491 38800 Telex: 849365 Hydro! G May 1991 Fax: 0491 32256 CONTENTS Page PROJECT AIMS 1 DATA COLLEC'TION 3 DATA MANAGEMENT 6 COMPUTER MODELLING 7 DERIVATION OF NATURALISED FLOWS 8 5.1 Methods 5.2 Summary of naturalised procedures for each site ASSESSMENT OF MODEL PREDICTIONS 13 CONCLUSIONS 17 FUTURE WORK 19 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 20 REFERENCES 21 APPENDIX 1. Notations uscd in the report APPENDIX 2. Notes on modelling and record extension of individual sites • 1. PROJECT AIMS The Colliford Model is a computer model which will represent the Colliford Reservoir System managed by South West Water Services Limited. Theoretical flows will be a major input into this computer model and the Institute of Hydrology was required to generate a record of synthetic natural daily mean flows at specified locations in the Colliford operational rcgion. Data were to be generated for up to fifty years where possible and in units of cumecs. Notes on how the data were derived were to accompany the generated data; a statistical comparison of the synthetic and historical flows is presented in this final report of the project. Synthetic -

The London Gazette, I?Th November 1961 8399

THE LONDON GAZETTE, I?TH NOVEMBER 1961 8399 DRAPKIN, Charles residing at HA, Brocklebank Road, REAY, Ronald, residing and carrying on business Fallowfield, Manchester, and carrying on business at 16, Chaucer Road, Sittingbourne, CHEMISTS' at 4A, Withy Grove, Manchester, 4, both in the SUNDRIESMAN, also carrying on business at 21, county of Lancaster, under the style of The Wind- Chaucer Road, Sittingbourne aforesaid, FURNI- mill Grill, as a RESTAURANT PRO- TURE DEALER, also carrying on business at 430, PRIETOR. Court—MANCHESTER. No. of Canterbury Street, Gillingham, all in .the county of Matter—60 of 1961. Date of Order—13th Nov., Kent, GREENGROCER. Court—ROCHESTER. 1961. Date of Filing Petition—13th Nov., 1961. No. of Matter—44 of 1961. Date of Order—15th Nov., 1961. Date of Filing Petition—15th Nov., FERMIN, Ann, of 5, Baker Street, Middlesbrough in 1961. the county of York (married woman), and carrying on business at The Espresso Pietro, 49, Borough TURiNER, Frederick Joseph Wallace (described in Road, Middlesbrough aforesaid, COFFEE BAR the Receiving Order as Frederick Turner), of 65, PROPRIETRESS. Court—MIDDLESBROUGH. The Terrace, Gravesend in the county of Kent, No. of Matter—19 of 19.61. Date of Order—13th 'LORRY DRIVER. Court—ROCHESTER. No. Nov., 1961. Date of Filing Petition—13th Nov., of Matter—40 of 1961. Date of Order—7th Nov., 1961. 1961. Date of Filing Petition—5th Oct., 1961. GRAY, Robert Ogle, residing at and lately carrying TUNNIOLIFFE, Leonard James, residing and carry- on business as a FARMER at Town Farm, East ing on business at 191, Liverpool Road, Pa trier oft, Sleekburn, Bedlington Station in the county of Eccles in the county of Lancaster, as a NEWS- Northumberland, Groundsman. -

River Water Quality 1992 Classification by Determinand

N f\A - S oo-Ha (jO$*\z'3'Z2 Environmental Protection Final Draft Report RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992 CLASSIFICATION BY DETERMINAND May 1993 Water Quality Technical Note FWS/93/005 Author: R J Broome Freshwater Scientist NRA CV.M. Davies National Rivers A h ority Environmental Protection Manager South West Region RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992 CLASSIFICATION BY DETERMINAND 1. INTRODUCTION River water quality is monitored in 34 catchments in the region. Samples are collected at a minimum frequency of once a month from 422 watercourses at 890 locations within the Regional Monitoring Network. Each sample is analysed for a range of chemical and physical determinands. These sample results are stored in the Water Quality Archive. A computerised system assigns a quality class to each monitoring location and associated upstream river reach. This report contains the results of the 1992 river water quality classifications for each determinand used in the classification process. 2. RIVER WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT The assessment of river water quality is by comparison of current water quality against River Quality Objectives (RQO's) which have been set for many river lengths in the region. Individual determinands have been classified in accordance with the requirements of the National Water Council (NWC) river classification system which identifies river water quality as being one of five classes as shown in Table 1 below: TABLE 1 NATIONAL WATER COUNCIL - CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM CLASS DESCRIPTION 1A Good quality IB Lesser good quality 2 Fair quality 3 Poor quality 4 Bad quality The classification criteria used for attributing a quality class to each criteria are shown in Appendix 1.