2004-12 Arms Flows in Eastern DR Congo.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Generale

P a g e | 1 INTRODUCTION GENERALE 0.1. Problématique Le présent mémoire porte sur les logotypes et la signification : Analyse de la dénotation et de la connotation des logotypes des banques Trust Merchant Bank (TMB) et Rawbank. En effet, Sperber1 dit qu’il n’y a rien de plus banal que la communication, car les êtres humains sont par nature des êtres communiquant par la parole, le geste, l’écrit, l’habillement et voire le silence, etc. La célèbre école de Palo Alto le dit tout haut aussi: on ne peut pas ne pas communiquer, tout est communication2. La communication, nous la pratiquons tous les jours sans y penser (mais également en y pensant) et généralement avec un succès assez impressionnant, même si parfois nous sommes confrontés à ses limites et à ses échecs. La communication demeure l’élément fondamental et complexe de la vie sociale qui rend possible l’interaction des personnes et dont la caractéristique essentielle est, selon Daniel Lagache3, la réciprocité. Elle est ce par quoi une personne influence une autre et en est influencée, car elle n’est pas indépendante des effets de son action. Morin affirme même que la communication a plusieurs fonctions : l’information, la connaissance, l’explication et la compréhension. Toutefois, pour lui, le problème central dans la communication humaine est celui de la compréhension, car on communique pour comprendre et se comprendre4. Raison pour laquelle, les chercheurs en matière de communication, surtout de notre ère, époque marquée par l’accroissement des entreprises dans la plupart des secteurs de la vie sociale, se trouvent confronté à de nouvelles problématiques qui sont autant d’enjeux pour améliorer la communication. -

Equateur Province Context

Social Science in Humanitarian Action ka# www.socialscienceinaction.org # # # Key considerations: the context of Équateur Province, DRC This brief summarises key considerations about the context of Équateur Province in relation to the outbreak of Ebola in the DRC, June 2018. Further participatory enquiry should be undertaken with the affected population, but given ongoing transmission, conveying key considerations for the response in Équateur Province has been prioritised. This brief is based on a rapid review of existing published and grey literature, professional ethnographic research in the broader equatorial region of DRC, personal communication with administrative and health officials in the country, and experience of previous Ebola outbreaks. In shaping this brief, informal discussions were held with colleagues from UNICEF, WHO, IFRC and the GOARN Social Science Group, and input was also given by expert advisers from the Institut Pasteur, CNRS-MNHN-Musée de l’Homme Paris, KU Leuven, Social Science Research Council, Paris School of Economics, Institut de Recherche pour le Développment, Réseau Anthropologie des Epidémies Emergentes, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Stellenbosch University, University of Wisconsin, Tufts University, Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica and others. The brief was developed by Lys Alcayna-Stevens and Juliet Bedford, and is the responsibility of the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform. Overview • Administrative structure – The DRC is divided into 26 provinces. In 2015, under terms of the 2006 Constitution, the former province of Équateur was divided into five provinces including the new smaller Équateur Province, which retained Mbandaka as its provincial capital.1 The province has a population of 2,543,936 and is governed by the provincial government led by a Governor, Vice Governor, and Provincial Ministers (e.g. -

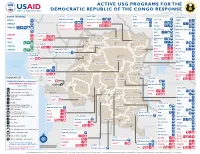

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic Main objectives Impact • UNHCR provided international protection to some In 2005, UNHCR aimed to strengthen the protection 204,300 refugees in the DRC of whom some 15,200 framework through national capacity building, registra- received humanitarian assistance. tion, and the prevention of and response to sexual and • Some of the 22,400 refugees hosted by the DRC gender-based violence; facilitate the voluntary repatria- were repatriated to their home countries (Angola, tion of Angolan, Burundian, Rwandan, Ugandan and Rwanda and Burundi). Sudanese refugees; provide basic assistance to and • Some 38,900 DRC Congolese refugees returned to locally integrate refugee groups that opt to remain in the the DRC, including 14,500 under UNHCR auspices. Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); prepare and UNHCR monitored the situation of at least 32,000 of organize the return and reintegration of DRC Congolese these returnees. refugees into their areas of origin; and support initiatives • With the help of the local authorities, UNHCR con- for demobilization, disarmament, repatriation, reintegra- ducted verification exercises in several refugee tion and resettlement (DDRRR) and the Multi-Country locations, which allowed UNHCR to revise its esti- Demobilization and Reintegration Programme (MDRP) mates of the beneficiary population. in cooperation with the UN peacekeeping mission, • UNHCR continued to assist the National Commission UNDP and the World Bank. for Refugees (CNR) in maintaining its advocacy role, urging local authorities to respect refugee rights. UNHCR Global Report 2005 123 Working environment Recurrent security threats in some regions have put another strain on this situation. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo ±

X Democratic Republic of the Congo UNHAS Routes - From 01 January 2021 20°0'0"E 30°0'0"E !ATTENTION ! Destinations may vary from the published order for optimum CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SOUTH SUDAN route utilization p DORUMA BANGUI ! p ! p ! DUNGU GBADOLITE !p ANGOp YAKOMA !( UYE !p NORD- !p LIBENGE UBANGI ENYELLE BAS-UELE HAUT- ARU UELE p X !p CAMEROON ! SUD- X ! UBANGI X MAHAGI MONGALA !p !p X ROE IMPFONDO MAKANZA !p RAMOGI p H ! !( X o BUBURU !(H !! TSHOPO BULakNe IA X X X ITURI Albert KISANGANI NOBILI !(p X BENI !p " EQUATEUR X 0 ' MBANDAKA X 0 ° X 0 p ! NORD- X X CONGO !(H INGENDE X KIVU TSHUAPA !(H PINGA UGANDA KIRUMBA BIKORO (!H !(H GABON KIWANDJA X (!H WALIKALE X !!oX GOMA XX Lake Kivu RWANDA LULINGU p !(HKIGULUBE! SHABUNDA BUKAVU KX INDU !(H !(H !(p X LODJA MIKENGE BURUNDI MAÏ-NDOMBE KOLE SUD- p H !(H UVIX RA KASAI !(H !( KIVU !( !(H SALAMABILA X MINEMBWE X H BRAZZAVILLE !(H !( HBARAKA ILEBO SANKURU !(H !p H!(KATANGA ! KWILU !!p !( !!o MANIEMA FIZI H H X KABAMBARE !( !( KINSHASA X LULIMBA X X X LOMAMI KONGOLO X KONGO !p TANZANIA CENTRAL X X NYUNZU X KANANGA o X !p !o KALEMIE ! X ! !p !p X ! ! X MBUJI-MAYI KABALO TSHIKAPA p Lake !! X KASAI- Tanganyika X ORIENTAL TANGANYKA KWANGO !p KASAI HAUT- p MOBA !MANONO ANGOLA CENTRAL LOMAMI (!H !p WALIKALE MASISI PWETO Focused view on Goma based Helicopter !o GOMA Lake Mweru ! !(p X X S Lake " 0 ' X 0 Kivu ° X 0 1 LUALABA BUKAVU LULINGU p HAUT- H ! !( KATANGA ZAMBIA X H LUBUMBASHI H KIGULUBE !( p SHABUNDA !( !( X SU±D-KIVU MIKENGE !(HUVIRA (!H !(HBIJOMBO X SALAMABILA !(H X !(H MINEMBWE !(H BARAKA H ± FIZI !( 0 25 50 !(H KATANGA Kilometers ± MANIEMA 0 125 250 KABAMBARE !(H LULIMBA!(H Kilometers Data sources: WFP-UNHAS, RGC, UNGIWG, Date Created: 12 February 2021 UNHAS - DHC8 (Kinshasa Based) UNHAS - C208B (Kalemie Based) Legend !!o UNHAS Based Aircraft Water Body CLUSTER LOGISTIC. -

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule Effective from 09th June 2021 AIRCRAFT MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:00 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:30 KINSHASA BRAZZAVILLE 08:45 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 UNO-234H 09:30 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 10:55 10:00 MBANDAKA YAKOMA 11:40 09:30 BRAZZAVILLE MBANDAKA 11:00 10:00 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 11:25 10:00 MBANDAKA LIBENGE 11:00 5Y-VVI 11:25 GBADOLITE BANGUI 12:10 12:10 YAKOMA MBANDAKA 13:50 11:30 MBANDAKA IMPFONDO 12:00 11:55 GBADOLITE MBANDAKA 13:20 11:30 LIBENGE BANGUI 11:50 DHC-8-Q400 13:00 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:20 14:20 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:50 12:30 IMPFONDO MBANDAKA 13:00 13:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:20 12:40 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE 14:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:20 13:30 MBANDAKA BRAZZAVILLE 15:00 14:30 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:00 15:30 BRAZZAVILLE KINSHASA 15:45 AD HOC CARGO FLIGHT TSA WITH UNHCR KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 08:00 KINSHASA KALEMIE 11:15 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 UNO-207H 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 11:45 KALEMIE GOMA 12:35 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 5Y-CRZ SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE EMB-145 LR 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 13:35 GOMA KINSHASA 14:50 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 -

Cycles Approved by OHRM for S

Consolidated list of duty stations approved by OHRM for rest and recuperation (R & R) (as of 1 July 2015) Duty Station Frequency R & R Destination AFGHANISTAN Entire country 6 weeks Dubai ALGERIA Tindouf 8 weeks Las Palmas BURKINA FASO Dori 12 weeks Ouagadougou BURUNDI Bujumbura, Gitega, Makamba, Ngozi 8 weeks Nairobi CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Entire country 6 weeks Yaoundé CHAD Abeche, Farchana, Goré, Gozbeida, Mao, N’Djamena, Sarh 8 weeks Addis Ababa COLOMBIA Quibdo 12 weeks Bogota COTE D’IVOIRE Entire country except Abidjan and Yamoussoukro 8 weeks Accra DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO Aru, Beni, Bukavu, Bunia, Butembo, Dungu, Goma, Kalemie, Mahagi, Uvira 6 weeks Entebbe Bili, Bandundu, Gemena, Kamina, Kananga, Kindu, Kisangani, Matadi, Mbandaka, Mbuji-Mayi 8 weeks Entebbe Lubumbashi 12 weeks Entebbe DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF KOREA Pyongyang 8 weeks Beijing ETHIOPIA Kebridehar 6 weeks Addis Ababa Jijiga 8 weeks Addis Ababa GAZA Gaza (entire) 8 weeks Amman GUINEA Entire country 6 weeks Accra HAITI Entire country 8 weeks Santo Domingo INDONESIA Jayapura 12 weeks Jakarta IRAQ Baghdad, Basrah, Kirkuk, Dohuk 4 weeks Amman Erbil, Sulaymaniah 8 weeks Amman KENYA Dadaab, Wajir, Liboi 6 weeks Nairobi Kakuma 8 weeks Nairobi KYRGYZSTAN Osh 8 weeks Istanbul LIBERIA Entire country 8 weeks Accra LIBYA Entire country 6 weeks Malta MALI Gao, Kidal, Tesalit 4 weeks Dakar Tombouctou, Mopti 6 weeks Dakar Bamako, Kayes 8 weeks Dakar MYANMAR Sittwe 8 weeks Yangon Myitkyina (Kachin State) 12 weeks Yangon NEPAL Bharatpur, Bidur, Charikot, Dhunche, -

EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE Democratic Republic of Congo

EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE Democratic Republic of Congo External Situation Report 2 Credit : B.Sensasi / WHO Uganda-2007 / WHO : B.Sensasi Credit Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment 1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE Democratic Republic of Congo External Situation Report 2 Date of information: 14 May 2018 ....................... ....................... ....................... Grade Cases Deaths CFR 1. Situation update 2 41 20 48.8% On 8 May 2018, the Ministry of Health (MoH) of the Democratic Republic of the Congo declared an outbreak of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in Bikoro Health Zone, Equateur Province. This is the ninth outbreak of Ebola virus disease over the last four decades in the country, with the most recent one occurring in May 2017. Context On 3 May 2018, the Provincial Health Division of Equateur reported 21 cases of fever with haemorrhagic signs including 17 community deaths in the Ikoko-Impenge Health Area in this region. A team from the Ministry of Health, supported by WHO and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) visited the Ikoko-Impenge Health Area on 5 May 2018 and detected five (5) active cases, two of whom were admitted to Bikoro General Hospital and three who were admitted in the health centre in Ikoko-Impenge. Samples were taken from each of the five active cases and sent for analysis at the Institute National de Recherche Biomédicale (INRB), Kinshasa on 6 May 2018. Of these, two tested positive for Ebola virus, Zaire ebolavirus species, by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on 7 May 2018 and the outbreak was officially declared on 8 May 2018. -

OCHA DRC Kinshasa Goma Kisangani Kisangani Bukavu Bunia

OCHA DRC Kinshasa Goma Kisangani Bukavu Bunia Mbandaka CONTEXT More than ever before since the onset of the war, the reporting period provided ample and eloquent arguments to perceive the humanitarian crisis in the DRC as a unique drama caused in the first place by unbridled violence, defiant impunity and ongoing violation of fundamental humanitarian principles. What comes first is the cold-blooded settlement of scores between two foreign troops in DRC’s third largest town, using heavy armament and ignoring humanitarian cease-fires in a total disregard for the fate of 600,000 civilians. Such exceptional circumstances led to the non less remarkable adoption of the UNSC Resolution 1304, marked by references to Chapter VII of the UN Charter, and by the presence of Ugandan and Rwandan Foreign ministers. Parallel to blatant violations of humanitarian principles, the level of daily mortality as a direct effect of the ongoing war in eastern DRC, as surveyed recently by International Rescue Committee, gives a horrific account of the silent disaster experienced by Congolese civilians in eastern provinces. Daily violence, mutual fears combined with shrinking access to most basic health services, are breeding an environment of vulnerability that led civilians of Kivu to portray themselves as the “wrecked of the earth”. In a poorly inhabited and remote province such as Maniema, an FAO mission estimated at 68% of the population the proportion of those who had to flee from home at one point since August 1998 (110,000 are still hiding in the forest). A third, most ordinary facet of DRC’s humanitarian crisis, is that witnessed by a humanitarian team in a village on the frontline in northern Katanga, where the absence of food and non food trade across the frontline (with the exception of discreet exchanges between troops) brings both displaced and host communities on the verge of starvation. -

Background Document DR Congo Information Sur La

Background document DR Congo Information sur la stratégie ‘pays’ avec la RD Congo Pour chaque pays partenaire du VLIR-UOS, une stratégie ‘pays’ a été élaborée. La stratégie pays représente la niche stratégique pour la coopération VLIR-UOS dans un pays, avec des domaines thématiques spécifiques et une orientation institutionnelle et / ou régionale, basée sur les besoins et priorités nationales du pays en matière d'enseignement supérieur et de développement. Le VLIR-UOS Stratégie pays pour DR Congo s’intègre à la stratégie de croissance et de réduction de la pauvreté de la RD Congo. Deux thèmes principaux de cette stratégie portent sur les ressources naturelles contribuant à la sécurité alimentaire et sur la reconstruction post-conflit. A cet effet, l’agriculture durable prend une place primordiale dans la coopération. Le programme RD Congo s’est élaboré autour de deux axes centraux : désenclavement et relève académique. Autres thèmes d’intervention sont la biodiversité, la santé et le développement social, le tout soutenu par une approche d’assurance qualité, avec une attention particulière sur les NTIC et l’anglais académique. Le VLIR-UOS collabore avec 7 institutions partenaires congolaises : Université de Kinshasa, Université de Kisangani, Université de Lubumbashi, Université Catholique du Congo, Université Catholique de Bukavu, Université Pédagogique Nationale and Institut Supérieur de Techniques Appliquées. Un promoteur souhaitant s'engager dans une coopération avec un institut partenaire hormis ces 7 partenaires listés, devra motiver dans la proposition de projet pourquoi une collaboration avec cet institut est jugée pertinente, comment la proposition est alignée à la stratégie pays et pourquoi il / elle présente une proposition avec l'institution partenaire proposée. -

2.5 Democratic Republic of Congo Waterways Assessment

2.5 Democratic Republic of Congo Waterways Assessment Company Information Travel Time Matrix Key Routes Below is a map of how waterways connect with railways in the Democratic Republic of Congo: The waterway network in the Democratic Republic of Congo has always been a key factor in the development of the country: the strategic use of its richness allows many possibilities in terms of transportation and electricity production. Below is a map of the ports and waterways network in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Page 1 The navigation network of inland waterways of the Democratic Republic of Congo totals more or less 16,000 km in length and is based on the Congo River and its major lakes. It is divided into four sections, called navigable reach, often connected by rail, including: The lower reach of the Congo River or the maritime in the west which totals 140 km from Banana (mouth) to the port of Matadi; The middle reach in the north and center of the Congo River Basin with its two axes (Kisangani-Kwamouth and Ilebo-Kwamouth) including two lakes (Maindombe and Tumba) and leading to Kinshasa; The upper reach in the east that goes from Ubundu to Province Orientale up to Lake Moero (Katanga Province) with two main axes Ubundu- Kindu and Kongolo-Bukama; The chain of lakes comprised of lakes Mweru, Tanganyika, Kivu, Edward and Albert. Until recently, management of inland navigation was carried out efficiently by the Board of Maritime Routes (RVM) on maritime reach and by the Board of Fluvial Routes (RVF) in the middle and upper reaches of Congo River. -

Province De L'equateur Profil Resume Pauvrete Et

Programme des nations unies pour le développement Unité de lutte contre la pauvreté RDC PROVINCE DE L’EQUATEUR PROFIL RESUME PAUVRETE ET CONDITIONS DE VIE DES MENAGES Mars 2009 - 1 – Province de L’Equateur Sommaire PROVINCE DE L’EQUATEUR Province Equateur Avant-propos..............................................................3 Superficie 403.292km² 1 – Présentation générale de l’Equateur....................4 Population 2005 5,8 millions 2 – La pauvreté dans l’Equateur ................................6 Densité 14 hab/km² Nb de communes 7 3 – L’éducation.........................................................10 Nb de territoires 8 4 – Le développement socio-économique des Routes d’intérêt national 2.939 km femmes.....................................................................11 Routes d’intérêt provincial 2.716 km 5 – La malnutrition et la mortalité infantile ...............12 Routes secondaires 3.158 km 6 – La santé maternelle............................................13 Réseau ferroviaire 187 km 7 – Le sida et le paludisme ......................................14 Gestion de la province Gouvernement Provincial 8 – L’habitat, l’eau et l’assainissement ....................15 Nb de ministres provinciaux 10 9 – Le développement communautaire et l’appui des Nb de députés provinciaux 108 Partenaires Techniques et Financiers (PTF) ...........16 - 2 – Province de L’Equateur Avant-propos Le présent rapport présente une analyse succincte des conditions de vie des ménages de la province de l’Equateur. L’analyse se base essentiellement sur les récentes enquêtes statistiques menées en RDC. Il fait partie d’une série de documents sur les conditions de vie de la population des 11 provinces de la RDC. Cette série de rapports constitue une analyse réalisée en toute indépendance par des experts statisticiens-économistes, afin de fournir une vision objective de la réalité de chaque province en se basant sur les principaux indicateurs de pauvreté et conditions de vie de la population, spécialement ceux se rapportant aux OMD et à la stratégie de réduction de la pauvreté.