Wildlands and Woodlands: a Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Threats to Cross-Border Wildlife Linkages in the Sky Islands Wildlands Network

Threats to Cross-Border Wildlife Linkages in the Sky Islands Wildlands Network Kim Vacariu Wildlands Project, Tucson, AZ Abstract—One of the greatest challenges facing conservationists in the Sky Islands region is finding a realistic means to maintain historic travel routes for wide-ranging species crossing the United States-Mexico border. This challenge is made difficult due to the ongoing efforts by the Federal government to install additional security infrastructure to stem the flood of undocumented immigrants now entering southern Arizona. Existing and proposed fencing, solid steel walls, all- night stadium lighting, vehicle barriers, an immense network of roads, a 24-hour flow of patrol vehicles, and low-level aircraft overflights are creating an impenetrable barrier to trans-border wildlife movement. Creative solutions are needed now. northern Mexico, and the Sky Islands of southeastern Arizona Introduction were maintained. In 2000, the Wildlands Project and regional partner groups, The SIWN CP identified numerous threats to a healthy including the Sky Island Alliance, published a conservation landscape in the Sky Islands, including fragmentation of plan covering more than 10 million acres of valuable wildlife habitat by roads, fences, and subdivisions; loss or extirpation habitat in the Sky Islands ecoregion of southeast Arizona and of numerous species; loss of natural disturbance regimes such southwest New Mexico. The document, known as the Sky as fire; loss of riparian areas, streams, and watersheds; inva- Islands Wildlands Network Conservation Plan (SIWN CP), is sion by exotic species; and loss of native forests to logging based on the basic tenets of conservation biology, and a sci- and other development. -

Sonoran Desert GEORGE GENTRY/FWSGEORGE the Sonoran Desert Has 2,000 Endemic Plant Species—More Than Anywhere Else in North America

in the shadow of the wall: borderlands conservation hotspots on the line Borderlands Conservation Hotspot 2. Sonoran Desert GEORGE GENTRY/FWSGEORGE The Sonoran Desert has 2,000 endemic plant species—more than anywhere else in North America. hink deserts are wastelands? A visit to one of the national monuments or national wildlife refuges in the Sonoran Desert could change your mind. These borderlands are teeming with plants and animals impressively adapted to extreme conditions. T During your visit you might encounter a biologist, a volunteer or a local activist in awe of the place and dedicated to protecting it. The Sonoran Desert is so important to the natural heritage of the United States and Mexico that both countries are vested in conservation lands and programs and on a joint mission to preserve it. “A border wall,” says one conservation coalition leader, “harms our mission” (Campbell 2017). The Sonoran Desert is one of the largest intact wild areas mountains, where they find nesting cavities and swoop in the country, 100,387 square miles stretching across the between cactuses and trees to hunt lizards and other prey. southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. This Rare desert bighorn sheep stick to the steep, rocky slopes of desert is renowned for columnar cactuses like saguaro, organ isolated desert mountain ranges where they keep a watchful pipe and cardón. Lesser known is the fact that the Sonoran eye for predators. One of the most endangered mammals in Desert has more endemic plant species—2,000—than North America, Sonoran pronghorn still occasionally cross anywhere else in North America (Nabhan 2017). -

The Wildlands Project Outside North America

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PDXScholar Portland State University PDXScholar Political Science Faculty Publications and Political Science Presentations 2003 The iW ldlands Project Outside North America David Johns Portland State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/polisci_fac Part of the Environmental Policy Commons, and the Political Science Commons Citation Details Johns, David. The iW ldlands Project Outside North America. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-27. 2003 This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wildlands Project Outside North America David M. Johns Abstract—The Wildlands Project seeks to create a connected greatly by the loss of connectivity. The legal boundaries of system of protected areas across North America that will ensure the protected areas were becoming actual boundaries as devel- survival of all native species, including top predators and wide- opment and conversion consumed intervening unprotected ranging species, in the context of fully functioning ecosystems. Core wildlands. These actual boundaries were biologically inad- protected areas are designated based on the biological needs of key equate to sustain species and processes over the long haul, species and the requirements of critical ecological processes. To even within the biggest islands like Yellowstone National work they must have, or will be restored to have, those attributes Park. -

Rewilding Earth Best of 2019 Rewilding Earth Best of 2019

Rewilding Earth Best of 2019 Rewilding Earth Best of 2019 Edited by John Davis & Susan Morgan Rewilding Earth Best of 2019 Edited by John Davis & Susan Morgan Essex Editions Rewilding Earth: Best of 2019 Copyright © 2020 Editors John Davis & Susan Morgan Cover Painting © Steven Kellogg Photos on Back Cover: Susan Morgan © John Miles John Davis © Kim Vacariu All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except for educational purposes or for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Published in the United States by Essex Editions. ISBN: 978-1-7335190-3-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020905445 Essex Editions Post O"ce Box 25 Essex, New York 12936 www.essexeditions.com [email protected] T#$%& '( C')*&)*+ Introduction by John Miles and Susan Morgan .................................................................................................. 1 Eagle Mountain Success by Jon Leibowitz .......................................................................................................... 3 Forever Wild by Sophi Veltrop ........................................................................................................................... 8 Adirondack Wildways Update by John Davis ..................................................................................................... 9 Wildlife Crossings -

Seeking Wildlands, Large and Small, for Carnivores Page 4 Do Wolves

$6.95 Seeking Wildlands, Large and Small, for Carnivores Page 4 Do Wolves Cause Trophic Cascades? Page 8 Wolf Population Status in Western United States: A Summary of State Reports Page 13 Shop Our 2015 Calendars Today! The Perfect Gift for Any Occasion. 16-Month Calendar $14.95 Item # 3801 12-Month Calendar $14.95 Item # 3803 Order today at shop.wolf.org or call 1-800-ELY-WOLF Your purchases help support the mission of the International Wolf Center. VOLUME 24, NO. 3 THE QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTER FALL 2014 4 Courtesy of Wildlands Network 8 National Park Service/Jim Peaco 13 Sherry Jokinen Seeking Wildlands, Large Do Wolves Cause Wolf Population Status and Small, for Carnivores Trophic Cascades? in Western United States: A Summary of State Reports On the 50th anniversary of the Ever since wolves were Wilderness Act, the attention of reintroduced into Yellowstone The wolf population in the western many is turned toward ensuring National Park, scientific studies United States is stabilizing and adequate wildlands for future have claimed that wolves were expanding its range. By 2012 generations of animals and humans. improving the ecosystem through wolves had been deemed recovered John Davis, co-founder of the “trophic cascades.” A trophic and delisted from the federal Wildlands Network, formerly the cascade is a set of reactions down endangered species list in Montana, Wildlands Project, explains why through a food pyramid starting Idaho, eastern Washington, eastern this is an important goal, what with an animal like the wolf at the Oregon, north-central Utah and is being done and what still top, elk in the middle and plants at Wyoming. -

Guiding-Principles-For-Rewilding.Pdf

Received: 27 October 2020 Revised: 19 February 2021 Accepted: 26 February 2021 DOI: 10.1111/cobi.13730 CONTRIBUTED PAPER Guiding principles for rewilding Steve Carver1 Ian Convery2 Sally Hawkins3 Rene Beyers4 Adam Eagle5 Zoltan Kun6 Erwin Van Maanen7 Yue Cao8 Mark Fisher9 Stephen R. Edwards10 Cara Nelson11 George D. Gann12,13 Steve Shurter14 Karina Aguilar15 Angela Andrade10,16 William J. Ripple17 John Davis18 Anthony Sinclair4 Marc Bekoff19 Reed Noss20 Dave Foreman18 Hanna Pettersson21 Meredith Root-Bernstein22,23,24 Jens-Christian Svenning25,26 Peter Taylor9 Sophie Wynne-Jones27 Alan Watson Featherstone28 Camilla Fløjgaard29 Mark Stanley-Price30 Laetitia M. Navarro31,32 Toby Aykroyd 33 Alison Parfitt9,† Michael Soulé34,† 1 School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK 2 National School of Forestry, University of Cumbria, UK 3 Institute of Science, Natural Resources and Outdoor Studies, University of Cumbria, UK 4 Biodiversity Research Centre, Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada 5 The Lifescape Project, London, UK 6 Wild Europe, Gyor,˝ Hungary 7 Rewilding Foundation, Diepenveen, The Netherlands 8 Institute for National Parks, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China 9 Wildland Research Institute, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK 10 Commission for Ecosystem Management, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland 11 W.A. Franke College of Forestry & Conservation, University of Montana, Missoula, USA 12 The Institute for Regional Conservation, Delray Beach, Florida, USA 13 Society for Ecological Restoration, -

Deeper Learning

ADEEPER STRATEGY PLANNINGLEARNING TOOL FORSO EVERYONE WESTERN CAN CONSERVATIONSUCCEED IN A CHANGING WORLD THE WILLIAM AND FLORA HEWLETT FOUNDATION EDUCATIONENVIRONMENT PROGRAM PROGRAM STRATEGIC PLAN MARCH 22,2011 2010 Prepared by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and Redstone Strategy Group TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................3 1. WHAT IS THE TOOL’S PURPOSE? .....................................................................5 The tool suggests philanthropic investments ........................................................... 5 The suggestions are based on expected return estimates ......................................... 6 These suggestions are one step in the planning process .......................................... 6 2. WHAT IS THE FOUNDATION’S GOAL FOR THE WEST? ..................................7 Ensuring ecological integrity from the Rockies to the Pacific .................................. 7 Ecological integrity has six main components ......................................................... 8 Targets are set for each component of ecological integrity ...................................... 9 3. WHAT CHANGES ARE NEEDED TO REACH THE GOAL? ..............................14 Integrity estimates take into account different levels of protection ....................... 14 Integrity is estimated based on intensity of human uses ....................................... 15 4. HOW CAN THE FOUNDATION IMPROVE ECOLOGICAL INTEGRITY? -

Gray Wolf Delisting Complaint

1 Jason Flanders (CA Bar No. 238007) Aqua Terra Aeris Law Group 2 4030 Martin Luther King Jr. Way Oakland, CA 94609 3 Ph: (916) 202-3018 [email protected] 4 John R. Mellgren, applicant for admission pro hac vice 5 Oregon Bar No. 114620 Western Environmental Law Center 6 120 Shelton McMurphey Blvd., Ste. 340 Eugene, OR 97401 7 Ph: 541-359-0090 [email protected] 8 Kelly E. Nokes, applicant for admission pro hac vice 9 Colorado Bar No. 51877 Western Environmental Law Center 10 P.O. Box 218 Buena Vista, Colorado 81211 11 Ph: 575-613-8051 [email protected] 12 Counsel for Plaintiffs 13 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 14 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 15 WILDEARTH GUARDIANS, a non-profit No. ______________ 16 organization; WESTERN WATERSHEDS PROJECT, a non-profit organization; 17 CASCADIA WILDLANDS, a non-profit COMPLAINT FOR organization; ENVIRONMENTAL DECLARATORY AND 18 PROTECTION INFORMATION CENTER, INJUNCTIVE RELIEF a non-profit organization; KLAMATH 19 FOREST ALLIANCE, a non-profit organization; KLAMATH-SISKIYOU 20 WILDLANDS CENTER, a non-profit organization; THE LANDS COUNCIL, a non- 21 profit organization; and WILDLANDS NETWORK, a non-profit organization, 22 Plaintiffs, 1 | COMPLAINT 25 3 1 vs. 2 DAVID BERNHARDT, as Secretary of the 3 United States Department of the Interior; the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE 4 INTERIOR, a federal department; the UNITED STATES FISH AND WILDLIFE 5 SERVICE, a federal agency; and AURELIA SKIPWORTH, as Director of the United States 6 Fish and Wildlife Service, 7 Federal Defendants. 8 INTRODUCTION 9 1. -

Science | Smithsonian 11/6/14, 9:06 AM

Can the World Really Set Aside Half of the Planet for Wildlife? | Science | Smithsonian 11/6/14, 9:06 AM ! " Search Search Smithsonian.com A bold conservation vision calls for a return to the South’s once-vast longleaf pine forests. (Carlton Ward Jr. ) Can the World Really Set Aside Half of the Planet for Wildlife? The eminent evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson has an audacious vision for saving Earth from a cataclysmic extinction event By Tony Hiss Smithsonian Magazine | Subscribe September 2014 “Battles are where the fun is,” said E.O. Wilson, the great evolutionary biologist, “and where the most rapid advances are made.” http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/can-world-really-set-aside-half-planet-wildlife-180952379/?all&no-ist Page 1 of 9 Can the World Really Set Aside Half of the Planet for Wildlife? | Science | Smithsonian 11/6/14, 9:06 AM We were sitting in oversized rocking chairs in a northwest Florida guest cottage with two deep porches and half-gallons of butter- pecan ice cream in the freezer, a Wilson favorite. He’d invited me here to look at what he considers a new approach to conservation, a new ecological Grail that, naturally, won’t happen without a fight. Wilson, 85, is the author of more than 25 books, many of which have changed scientific understanding of human nature and of how the living part of the planet is put together. Known as the father of sociobiology, he is also hailed as the pre-eminent champion of biodiversity: Wilson coined the word “biophilia” to suggest that people have an innate affinity for other species, and his now widely accepted “theory of island biogeography” explains why national parks and all confined landscapes inevitably lose species. -

Rewilding: the Realisation and Reality of a New Challenge for Nature in the Twenty-First Century

29 Rewilding: the Realisation and Reality of a New Challenge for Nature in the Twenty-first Century Erwin van Maanen and Ian Convery Introduction The domestication of Earth Much of this book has considered the history of our changing perceptions of nature. In this final chapter we would like to focus on rewilding: a bold new approach that offers the potential to dramatically change our relationship with nature in the twenty-first century. The ideas for the chapter crystallised during a hike in Cox Scrub Conservation Park, an arid native scrub reserve located on the Fleurieu Peninsula, south of Adelaide in Australia. At only 5.44 km2, the reserve is, by Australian standards, a ‘postage stamp’. It is also quite difficult to observe wildlife in the reserve; only a lone ring-tailed possum sitting atop a tree in the scorching heat provided some indication of life. The surrounding landscape has become largely pastoral, with orchards and wineries now encroaching along the border of the reserve, and filling in former sheep pastures. Wildness has been drawn largely out of the reserve by progressive dewilding; global landscapes, it would seem, are becoming increasingly homogenised. The coastline between Adelaide and Melbourne must have looked very different back in the early ninteenth century when the English natural historian John Gould was surveying and collecting specimens on the peninsula (see Fig 29.1). Whilst one can imagine the difficulties Gould faced exploring this wild, beautiful but hostile environment, it would be wrong to assume that this landscape was without human influence, though it is likely that the landscape manage- ment of Aboriginal communities, who had shaped the landscape for more than 45,000 years, was largely lost on Gould and other early explorers of the Australian continent. -

Explanatory Guide on Target 11 of the Strategic Plan For

Explanatory Guide on Target 11 Of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 1 A guide to Target 11 of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 1. Introduction 2. Why is a target needed 3. Explanation of key terms 3.1 “At least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas” -What are terrestrial and inland waters? - What is the current status of terrestrial protected areas? 3.2 “10 per cent of coastal and marine areas” - What are coastal and marine areas? - What is the current status of marine protected areas/ 3.3 “Areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services” - What are areas of particular importance of biodiversity? - Ecosystem services of protected areas 3.4 “Ecologically representative” -What is ecologically representative? 3.5 “ Effectively and equitably managed” - What is effectively managed? - What aspects of management effectiveness are usually included in an assessment? - What is equitably managed? - What is protected area governance? 3.6 “Well connected systems of protected areas and integrated into wider landscape and seascape” - Why protected areas need to be connected? - What is an ecological network? - What is protected area integration? - What are broader landscapes and seascapes and what are related sectors - What are the benefits of integrating protected areas into wider landscapes and seascapes 3.7 Other effective area-based conservation measures” - What are “other area-based conservation measures”? - What are Indigenous and Community Conservation Areas? - What is the coverage of ICCAs? - What is the significance of ICCAs? 4. How to set a national target 2 5. How to achieve the national and global targets and sub-targets 5.1 Action plan for implementing PoWPA 5.2 GEF 5 allocations 6. -

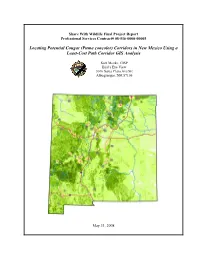

Locating Potential Cougar (Puma Concolor) Corridors in New Mexico Using a Least-Cost Path Corridor GIS Analysis

Share With Wildlife Final Project Report Professional Services Contract# 08-516-0000-00005 Locating Potential Cougar (Puma concolor) Corridors in New Mexico Using a Least-Cost Path Corridor GIS Analysis Kurt Menke, GISP Bird’s Eye View 3016 Santa Clara Ave SE Albuquerque, NM 87106 May 31, 2008 Introduction & Background ............................................................................................ 3 House Joint Memorial 3.............................................................................................. 3 New Mexico Highlands Wildlands Network Design.................................................. 3 NMDOT and NMDGF Plans...................................................................................... 4 Species Selection ........................................................................................................ 4 Habitat Fragmentation ................................................................................................ 4 Methodology................................................................................................................... 5 Habitat Suitability Model............................................................................................ 5 Identifying Potential Corridor Locations.................................................................... 7 Corridor Termini......................................................................................................... 7 Least Cost Path Analysis ...........................................................................................