Media Globalization and Its Effect Upon International Communities: Seeking a Communication Theory Perspective Jeffrey K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television, Mass Media, and Environmental Cultivation

TELEVISION, MASS MEDIA, AND ENVIRONMENTAL CULTIVATION: A STUDY OF PRIVATE FOREST LANDOWNERS IN DELAWARE by John George Petersen A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Fall 2013 © 2013 John George Petersen All Rights Reserved TELEVISION, MASS MEDIA, AND ENVIRONMENTAL CULTIVATION: A STUDY OF PRIVATE FOREST LANDOWNERS IN DELAWARE by John George Petersen Approved: __________________________________________________________ Nancy Signorielli, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: _________________________________________________________ Elizabeth M. Perse, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Communication Approved: _________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: _________________________________________________________ James G. Richards, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study would not have been possible without the financial support of the U.S. Forest Service and its Forest Stewardship Program as well as technical assistance from the Delaware Department of Agriculture and the Delaware Forest Service. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the faculty and fellow students of the University of Delaware’s Department of Communication for pointing me in the right direction and handing me the chart and compass to complete my academic journey. In particular, I would like to offer special thanks to the members of my thesis committee: Carolyn White Bartoo, Elizabeth Perse, Ph.D., and Nancy Signorielli, Ph.D., for their guidance and thoughtful feedback. In particular, Dr. Signorielli is not only an exceptional educator who has always given of her time, energy, and talents to help her students and colleagues, but also stands as a pioneer in communication theory whose research has made invaluable contributions to the advancement of cultivation analysis and media studies. -

The Cultivation Theory and Reality Television

1 The Cultivation Theory and Reality Television: An Old Theory With a Modern Twist Jeffrey Weiss CM490: Senior Seminar II Dr. Lisa Holderman and Professor Alan Powell April 16, 2020 2 The Cultivation Theory The cultivation theory is a widely regarded theory spanning across the communications realm. It analyzes the long term effects of television on people. The theory states that what people may view on television will determine their outlook on reality in the world. The theory was developed by George Gerbner and Larry Gross in 1975. Their research started off in the 1960s, where they analyzed people’s perception of what they saw on television, and compared it to everyday life. The theory has covered other types of media but television was the first motion visual type of media, igniting a new era of technology and media. Television erupted during this time period, as more and more Americans were transitioning from radio to television. This switch led to heavy amounts of visual media, which has demonstrated a huge mass of people confusing what they see on television and the real world. Gerbner was intrigued to find out that television formed a bond between people and television. TV was becoming an American staple, and as more and more people started watching it, a steady string of effects arose. People’s real world attitudes were changing. Visually speaking, people’s emotions and opinions were connected with what they saw on TV. The cultivation theory arose as a project titled the Cultural Indicators Project. It was commissioned by former president Lynden B. -

Benbella Spring 2020 Titles

Letter from the publisher HELLO THERE! DEAR READER, 1 We’ve all heard the same advice when it comes to dieting: no late-night food. It’s one of the few pieces of con- ventional wisdom that most diets have in common. But as it turns out, science doesn’t actually support that claim. In Always Eat After 7 PM, nutritionist and bestselling author Joel Marion comes bearing good news for nighttime indulgers: eating big in the evening when we’re naturally hungriest can actually help us lose weight and keep it off for good. He’s one of the most divisive figures in journalism today, hailed as “the Walter Cronkite of his era” by some and deemed “the country’s reigning mischief-maker” by others, credited with everything from Bill Clinton’s impeachment to the election of Donald Trump. But beyond the splashy headlines, little is known about Matt Drudge, the notoriously reclusive journalist behind The Drudge Report, nor has anyone really stopped to analyze the outlet’s far-reaching influence on society and mainstream journalism—until now. In The Drudge Revolution, investigative journalist Matthew Lysiak offers never-reported insights in this definitive portrait of one of the most powerful men in media. We know that worldwide, we are sick. And we’re largely sick with ailments once considered rare, including cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. What we’re just beginning to understand is that one common root cause links all of these issues: insulin resistance. Over half of all adults in the United States are insulin resistant, with other countries either worse or not far behind. -

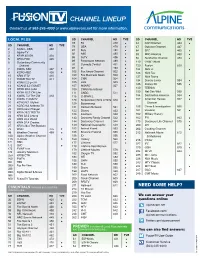

Channel Lineup

CHANNEL LINEUP Contact us at 563-245-4000 or www.alpinecom.net for more information. LOCAL PLUS SD CHANNEL HD TVE SD CHANNEL HD TVE 78 FX 478 44 Golf Channel 444 SD CHANNEL HD TVE 79 USA 479 47 Outdoor Channel 447 2 KGAN - CBS 402 81 Syfy 481 64 SEC 465 3 Alpine TV 85 A&E 485 83 BBC America 483 4 KPXR 48 ION 404 86 truTV 486 5 KFXA FOX 405 84 Sundance Channel 484 89 Paramount Network 489 6 Guttenberg Community 110 CNBC World Channel 91 Comedy Central 491 120 Fusion 520 7 KWWL NBC 407 93 E! 493 124 Nick Jr. 102 Fox News Channel 502 9 KCRG ABC 409 126 Nick Too 103 Fox Business News 503 10 KRIN IPTV 410 127 Nick Toons 104 CNN 504 11 KWKB This TV 411 134 Disney Junior 534 13 KGAN 2.2 getTV 105 HLN 505 136 Disney XD 536 14 KGAN3 2.3 COMET 107 MSNBC 507 140 TEENick 15 KPXR 48.2 qubo 109 CNN International 16 KPXR 48.3 ION Life 111 CNBC 511 150 Nat Geo Wild 550 18 KWWL 7.2 The CW 418 116 C-SPAN 2 154 Destination America 554 19 KWWL 7.3 MeTV 123 Nickelodeon/Nick At Nite 523 157 American Heroes 557 20 KCRG 9.2 MyNet 129 Boomerang Channel 21 KCRG 9.3 Antenna TV 131 Cartoon Network 531 158 Crime & Investigation 558 22 KFXA 28.2 Charge! 133 Disney 533 161 Viceland 561 23 KFXA 28.3 TBD TV 138 Freeform 538 162 Military History 24 KRIN 32.2 Learns 143 Discovery Family Channel 543 163 FYI 563 25 KRIN 32.3 World 26 KRIN 32.4 Creates 144 Discovery Channel 544 175 Discovery Life Channel 575 27 KFXA 28.4 The Stadium 149 National Geographic 549 200 DIY 75 WGN 475 153 Animal Planet 553 203 Cooking Channel 99 Weather Channel 499 155 Science Channel 555 212 Hallmark -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Cultivation Theory and Medical Dramas

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 CULTIVATING MIRACLE PERCEPTIONS: CULTIVATION THEORY AND MEDICAL DRAMAS Rachael A. Record University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Record, Rachael A., "CULTIVATING MIRACLE PERCEPTIONS: CULTIVATION THEORY AND MEDICAL DRAMAS" (2011). University of Kentucky Master's Theses. 148. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_theses/148 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF THESIS CULTIVATING MIRACLE PERCEPTIONS: CULTIVATION THEORY AND MEDICAL DRAMAS This thesis reports the results of a study designed to investigate the influence of exposure to televised medical dramas on perceptions of medical miracles. Four hundred and eighty-one college students participated in a survey in which they responded to different questions about their medical drama viewership and their different beliefs with regard to medical miracles. Results found that heavy medical drama viewers perceived belief in medical miracles to be less normal than non-viewers. Similarly, heavy viewers perceived medical miracles to occur less often than non-viewers. Interestingly, heavy viewers perceived medical dramas to be less credible than non-viewers. In addition, this study found that personal experience with medical miracles affected responses across all three measured viewership levels. The study concludes that, when compared to no exposure to medical dramas, heavy exposure has the potential for creating a more realistic view of medical miracles. -

The Cultivation Theory

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: A Arts & Humanities - Psychology Volume 15 Issue 8 Version 1.0 Year 2015 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X All you Need to Know About: The Cultivation Theory By Eman Mosharafa City University of New York, United States Introduction- In this paper, the researcher comprehensively examines the cultivation theory. Conceptualized by George Gerbner in the 1960s and 1970s, the theory has been questioned with every media technological development. In the last six decades, the mass communication field witnessed the propagation of cable, satellite, video games and most recently social media. So far, the theory seems to have survived by continuous adjustment and refinement. Since 2000, over 125 studies have endorsed the theory, which points out to its ability to adapt to a constantly changing media environment. This research discusses the theory since its inception, its growth and expansion, and the future prospects for it. In the first section of the paper, an overview is given on the premises/founding concepts of the theory. Next is a presentation of the added components to the theory and their development over the last sex decades including: The cultivation analysis, the conceptual dimensions, types and measurement of cultivation, and the occurrence of cultivation across the borders. GJHSS-A Classification : FOR Code: 130205p AllyouNeedtoKnowAboutTheCultivationTheory Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2015. Eman Mosharafa. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Chasing Success: a Cultivated Reality

Chasing Success: A Cultivated Reality BY Anastasia Bevillard ADVISOR • Stanley Baran _________________________________________________________________________________________ Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors in the Bryant University Honors Program April 2018 Table of Contents ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………………………...1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 2 LITERATURE REVIEW.......................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4 Background/History .............................................................................................................. 4 Review................................................................................................................................... 6 In Summation .................................................................................................................... ..22 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY: CULTIVATION ANALYSIS……………………..…......22 RESEARCH AND RESULTS……………………………………………………………….23 Message System Analysis ................................................................................................... 23 Actual Reality Versus Music Video Reality ....................................................................... 27 Young Adults’ Social Realities .......................................................................................... -

A Critical Historical Overview of Media Approaches

Medij. istraž. (god. 7, br. 1-2) 2001. (45-67) PREGLEDNI RAD UDK: 316.77 316.01 Primljeno: 17.10.2001. A Critical Historical Overview of Media Approaches Zala Volčič* SUMMARY The article offers an overview of the main approaches to the media and introduces the reader to the most influential media theories. It deals with the historical develop- ment of the relationship of media, culture, society, and the public. It traces the devel- opment of different notions of culture, their impacts on the media, and their relation- ships to various conceptions of “the public”. It draws on this history to explore cur- rent debates about the influences of the media and society on public life. In the first part, the paper deals with some issues of the relation between theories of communica- tion and theories of society. It grounds the study of the media and communication in the classical social theory and in the context of liberal pragmatism (Chicago School). It tries to answer the questions such as how Dewey, Lippman, Mead, et al. conceptu- alize the media and communications and what theoretical assumptions underlie liberal pragmatism. Further, it seeks to explore the differences between Mass Communication research (Media Effects Tradition) and Critical Theory (the Frankfurt School). The main question in this section is how the ideas of thinkers associated with the “critical” tradition compare with those of the “liberal” and “media effects” traditions. The arti- cle also focuses on the differences between British Cultural Studies and the American version of cultural studies. Lastly, it reviews the debate in Feminist and Audience ap- proaches to the media. -

WBU Radio Guide

FOREWORD The purpose of the Digital Radio Guide is to help engineers and managers in the radio broadcast community understand options for digital radio systems available in 2019. The guide covers systems used for transmission in different media, but not for programme production. The in-depth technical descriptions of the systems are available from the proponent organisations and their websites listed in the appendices. The choice of the appropriate system is the responsibility of the broadcaster or national regulator who should take into account the various technical, commercial and legal factors relevant to the application. We are grateful to the many organisations and consortia whose systems and services are featured in the guide for providing the updates for this latest edition. In particular, our thanks go to the following organisations: European Broadcasting Union (EBU) North American Broadcasters Association (NABA) Digital Radio Mondiale (DRM) HD Radio WorldDAB Forum Amal Punchihewa Former Vice-Chairman World Broadcasting Unions - Technical Committee April 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 5 WHAT IS DIGITAL RADIO? ....................................................................................................................... 7 WHY DIGITAL RADIO? .............................................................................................................................. 9 TERRESTRIAL -

Media Literacy and Response to Terror News

D. Bergan and H. Lee | Journal of Media Literacy Education 2018 10(3), 43 - 56 Available online at www.jmle.org The National Association for Media Literacy Education’s Journal of Media Literacy Education 10 (3), 43 - 56 Media Literacy and Response to Terror News Daniel Bergan Heysung Lee Michigan State University ABSTRACT Increased fear and threat toward terrorism in the current American society is largely due to vivid news coverages, as explained by cultivation theory and mean world syndrome. Media literacy has potential to reduce this perception of fear and threat, such as people high on media literacy will be less likely to be affected by terror news. We focus on representation and reality for investigating the relationship between influence of terror news and media literacy, one component of media literacy framework developed by Primack and Hobbs (2006), which deals with how media messages represent reality. Our study divided participants into two groups, reading terror news or another news without any threat, and measured their levels of media literacy. The results show that media literacy does not reduce the influence of terror news. More solid theory of media literacy is needed in order to resolve this impasse and explain impact of media use on perception of hazardous world. Keywords: media literacy, news, terrorism, mass communication Since the 9/11 terror attacks, Americans have felt threatened by terrorism (Norris, Kern, & Just, 2003). Polling shows that about half (48%) of Americans worry about terror attacks in the U.S. (Gallup, 2016). However, terrorist attacks have actually declined around the world, and terror attacks tend to be concentrated in the Middle East, not North America, according to U.S.