British Governments, Colonial Consumers, and Continental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Topiary to Utopia? Ending Teleology and Foregrounding Utopia in Garden History

Cercles 30 (2013) FROM TOPIARY TO UTOPIA? ENDING TELEOLOGY AND FOREGROUNDING UTOPIA IN GARDEN HISTORY LAURENT CHÂTEL Université Paris-Sorbonne (Paris IV) / CNRS-USR 3129 Introduction, or the greening of Utopia Utopia begs respect. More than an island, imagined or imaginary, more than a fiction, it is a word, a research area, almost a science. Utopia has lent itself to utopologia and utopodoxa, and there are utopologues and utopolists. To think out utopia is to think large and wide; to reflect on man’s utopian propensity (which strikes me as deeply, ontologically rooted) is to ponder over man’s extraversive or centrifugal dimension, whereby being in one universe (perhaps feeling constrained) he/she feels the need to re-authorise himself/herself as Architect, “skilful Gardener”, and to multiply universes within his own universe. Utopia points to an opening up of frontiers, a breaking down of dividing walls: it is about transferring other worlds into one world as if man needed to think constantly he had a plurality of worlds at hand. Our culture today is full of this taste for derivation, analogy, parallel, and mirror-effects. A photographer like Aberlado Morell has played with his irrepressible need to fuse the world ‘within’ and the world ‘without’ by offering “views with a room”.1 Nothing new there- a recycling of past techniques of image-merging such as capriccio fantasies. But such a propensity to invent and re-invent a multi-universe reaches out far and wide in contemporary global society. However, from the 1970s onwards, utopia has been declared a thing of the past - no longer a valid thinking tool of this day and age possibly because of 1 See the merging of inside and outside perspectives on his official website (last checked 21 April 2013), http://www.abelardomorell.net/ Laurent Châtel, « From Topiary to Utopia ? Ending Teleology and Foregrounding Utopia in Garden History », Cercles 30 (2013) : 95-107. -

A Case Study of Samuel Adams and Thomas Hutchinson

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2007 Reputation in Revolutionary America: A Case Study of Samuel Adams and Thomas Hutchinson Elizabeth Claire Anderson University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Anderson, Elizabeth Claire, "Reputation in Revolutionary America: A Case Study of Samuel Adams and Thomas Hutchinson" (2007). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1040 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elizabeth Claire Anderson Bachelor of Arts 9lepu.tation in ~ Unwtica: a ~e studq- oj Samuel a.dartt;., and g fuun.a:, !JtulcIiUu,on 9JetIi~on !lWWuj ~ g~i6, Sp~ 2007 In July 1774, having left British America after serving terms as Lieutenant- Governor and Governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson met with King George III. During the conversation they discussed the treatment Hutchinson received in America: K. In such abuse, Mf H., as you met with, I suppose there must have been personal malevolence as well as party rage? H. It has been my good fortune, Sir, to escape any charge against me in my private character. The attacks have been upon my publick conduct, and for such things as my duty to your Majesty required me to do, and which you have been pleased to approve of. -

Addendum: University of Nottingham Letters : Copy of Father Grant’S Letter to A

Nottingham Letters Addendum: University of 170 Figure 1: Copy of Father Grant’s letter to A. M. —1st September 1751. The recipient of the letter is here identified as ‘A: M: —’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 171 Figure 2: The recipient of this letter is here identified as ‘Alexander Mc Donell of Glengarry Esqr.’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 172 Figure 3: ‘Key to Scotch Names etc.’ (NeC ¼ Newcastle of Clumber Mss.). Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 173 Figure 4: In position 91 are the initials ‘A: M: —,’ which, according to the information in NeC 2,089, corresponds to the name ‘Alexander Mc Donell of Glengarry Esqr.’, are on the same line as the cant name ‘Pickle’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. Notes 1 The Historians and the Last Phase of Jacobitism: From Culloden to Quiberon Bay, 1746–1759 1. Theodor Fontane, Jenseit des Tweed (Frankfurt am Main, [1860] 1989), 283. ‘The defeat of Culloden was followed by no other risings.’ 2. Sir Geoffrey Elton, The Practice of History (London, [1967] 1987), 20. 3. Any subtle level of differentiation in the conclusions reached by participants of the debate must necessarily fall prey to the approximate nature of this classifica- tion. Daniel Szechi, The Jacobites. Britain and Europe, 1688–1788 (Manchester, 1994), 1–6. -

Philipp Robinson Roessner MA FSA Scot

SCOTTISH FOREIGN TRADE TOWARDS THE END OF THE PRE- INDUSTRIALPERIOD, 1700-1760 Philipp Robinson Roessner MA FSA Scot PhD The University of Edinburgh 2007 312 PART II: SCOTTISH-GERMAN TRADE, 1700-1770: A CASESTUDY 7.1 Embeddedness of Early Modern Scottish-GermanTrade 313 7 Scottish Trade with Germany, 1700-1770: The Macro-Picture 7.1 The Embeddedness of Early Modern Scottish-German Trade So far the structure, trends and fluctuations in the Scottish trade volume between 1700 and 1760, the last decades of Scotland's pre-industrial period, have been discussed. It could be shown that after 1730, trade levels began to expand significantly, probably matching or surpassing all growth rates realized during previous decades, if not centuries. Scotland underwent her own "commercial revolution", yet on terms decidedly different from England. Overseas trade levels tripled between 1700 and 1760. But trade levels remained small, both in comparison to England, as well as in relation to Scotland's national income. Trade was furthermore biased towards the importation and re-exportation of colonial foodstuffs, particularly tobacco. This peculiar Scottish trading pattern was conditioned by the structure of the domestic economy and the inclusion of Scottish ports and merchants into the English commercial empire (Navigation Acts). On the one hand, the Scottish manufacturing base was weak. The domestic economy neither exported particularly large amounts and shares of her production, nor was it heavily reliant upon imports from overseas.Accordingly, average imports of tobacco, sugar and rum from the Americas far outpacedyearly averagedomestic exports of linen, woollen, leather and other manufactures to that region. -

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, by PAUL E

LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Class Iftttoergibe 1. ANDREW JACKSON, by W. G. BROWN. 2. JAMES B. EADS, by Louis How. 3. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, by PAUL E. MORE. 4. PETER COOPER, by R. W. RAYMOND. 5. THOMAS JEFFERSON, by H. C. MKR- WIN. 6. WILLIAM PENN, by GEORGE HODGBS. 7. GENERAL GRANT, by WALTER ALLEN. 8. LEWIS AND CLARK, by WILLIAM R. LIGHTON. 9. JOHNMARSHALL.byjAMEsB.THAYER. 10. ALEXANDER HAMILTON, by CHAS. A. CONANT. 11. WASHINGTON IRVING, by H.W.BoYN- TON. 12. PAUL JONES, by HUTCHINS HAPGOOD. 13. STEPHEN A. DOUGLAS, by W. G. BROWN. 14. SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN, by H. D. SEDGWICK, Jr. Each about 140 pages, i6mo, with photogravure portrait, 65 cents, net ; School Edition, each, 50 cents, net. HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY BOSTON AND NEW YORK fotorafoe Biographical Series NUMBER 3 BENJAMIN FRANKLIN BY PAUL ELMER MORE UNIV. or CALIFORNIA tv ...V:?:w BENJAMIN FRANKLIN BY PAUL ELMEK MORE BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY fftiteitfibe pre0 Camferibge COPYRIGHT, igOO, BY PAUL E. MORE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CONTENTS CHAP. **< I. EARLY DAYS IN BOSTON .... 1 II. BEGINNINGS IN PHILADELPHIA AND FIRST VOYAGE TO ENGLAND .... 22 III. RELIGIOUS BELIEFS. THE JUNTO . 37 " IV. THE SCIENTIST AND PUBLIC CITIZEN IN PHIL ADELPHIA 52 V. FIRST AND SECOND MISSIONS TO ENGLAND . 85 VI. MEMBER OF CONGRESS ENVOY TO FRANCE 109 227629 BENJAMIN FRANKLIN EAKLY DAYS IN BOSTON WHEN the report of Franklin s death reached Paris, he received, among other marks of respect, this significant honor by one of the revolutionary clubs : in the cafe where the members met, his bust was crowned with oak-leaves, and on the pedestal below was engraved the single word VIR. -

The American Revolution Presentation

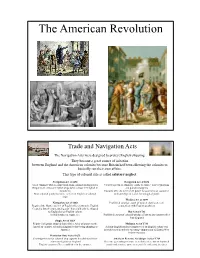

The American Revolution Trade and Navigation Acts The Navigation Acts were designed to protect English shipping. ! They became a great source of irritation between England and the American colonies because Britain had been allowing the colonies to basically run their own affairs. ! This type of colonial rule is called salutary neglect. Navigation Act of 1651 Navigation Act of 1696 Goal: eliminate Dutch competition from colonial trading routes Created system of admiralty courts to enforce trade regulations Required all crews on English ships to be at least 1/2 English in and punish smugglers nationality Customs officials were given power to issue writs of assistance Most colonial goods had to be carried on English or colonial to board ships to search for smuggled goods ships ! ! Woolens Act of 1699 Navigation Act of 1660 Prohibited colonial export of woolen cloth to prevent Required the Master and 3/4 of English ship crews to be English competition with English producers Created a list of "enumerated goods” that could only be shipped ! to England or an English colony Hat Act of 1732 included tobacco, sugar, rice Prohibited export of colonial-produced hats to any country other ! than England Staple Act of 1663 ! Required all goods shipped from Africa, Asia, or Europe to the Molasses Act of 1733 American colonies to land in England before being shipping to All non-English molasses imported to an English colony was America heavily taxed in order to encourage importation of British West ! Indian molasses Plantation Duty Act of 1673 ! Created -

The Americans

UUNNIITT AmericanAmerican BeginningsBeginnings CHAPTER 1 Three Worlds Meet toto 17831783 Beginnings to 1506 CHAPTER 2 The American Colonies Emerge 1492–1681 CHAPTER 3 The Colonies Come of Age 1650–1760 CHAPTER 4 The War for Independence 1768–1783 UNIT PROJECT Letter to the Editor As you read Unit 1, look for an issue that interests you, such as the effect of colonization on Native Americans or the rights of American colonists. Write a letter to the editor in which you explain your views. Your letter should include reasons and facts. The Landing of the Pilgrims, by Samuel Bartoll (1825) Unit 1 1 View of Boston, around 1764 1693 The College of William and 1651 English Parliament 1686 James II creates Mary is chartered passes first of the the Dominion of New in Williamsburg, Navigation Acts. England. Virginia. AMERICAS 1650 1660 1670 1680 1690 1700 WORLD 1652 Dutch settlers 1660 The English 1688 In England the Glorious establish Cape Town monarchy is restored Revolution establishes the in South Africa. when Charles II supremacy of Parliament. returns from exile. 64 CHAPTER 3 INTERACT WITH HISTORY The year is 1750. As a hard-working young colonist, you are proud of the prosperity of your new homeland. However, you are also troubled by the inequalities around you—inequalities between the colonies and Britain, between rich and poor, between men and women, and between free and enslaved. How can the colonies achieve equality and freedom? Examine the Issues • Can prosperity be achieved without exploiting or enslaving others? • What does freedom mean, beyond the right to make money without government interference? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 3 links for more information related to The Colonies Come of Age. -

Ch. 3 Section 4: Life in the English Colonies Colonial Governments the English Colonies in North America All Had Their Own Governments

Ch. 3 Section 4: Life in the English Colonies Colonial Governments The English colonies in North America all had their own governments. Each government was given power by a charter. The English monarch had ultimate authority over all of the colonies. A group of royal advisers called the Privy Council set English colonial policies. Colonial Governors and Legislatures Each colony had a governor who served as head of the government. Most governors were assisted by an advisory council. In royal colonies the English king or queen selected the governor and the council members. In proprietary colonies, the proprietors chose all of these officials. In a few colonies, such as Connecticut, the people elected the governor. In some colonies the people also elected representatives to help make laws and set policy. These officials served on assemblies. Each colonial assembly passed laws that had to be approved first by the advisory council and then by the governor. Established in 1619, Virginia's assembly was the first colonial legislature in North America. At first it met as a single body, but was later split into two houses. The first house was known as the Council of State. The governor's advisory council and the London Company selected its members. The House of Burgesses was the assembly's second house. The members were elected by colonists. It was the first democratically elected body in the English colonies. In New England the center of politics was the town meeting. In town meetings people talked about and decided on issues of local interest, such as paying for schools. -

Creating Economy: Merchants in Seventeenth-Century England

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 12-11-2017 Creating Economy: Merchants in Seventeenth-Century England Braxton Hall Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Hall, Braxton, "Creating Economy: Merchants in Seventeenth-Century England." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREATING ECONOMY: MERCHANTS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND by BRAXTON HALL Under the Direction of Jacob Selwood, PhD ABSTRACT Between 1620 and 1700, merchants in England debated the economic framework of the kingdom. The system they created is commonly referred to as ‘mercantilism’ and many historians have concluded that there was a consensus among economists that supported the balance of trade and restricted foreign markets. While that economic consensus existed, merchants also had to adopt new ways of thinking about religion, foreigners, and naturalization because of the system they created. Merchants like Josiah Child in the latter part of the seventeenth century were more acceptant of strangers and they were more tolerant of religion that their predecessors -

Governor Francis Bernard and the Origins of the American Revolution

1 Governor Francis Bernard and the Origins of the American Revolution. Paper delivered to Modern History Research Seminar Series, University of Edinburgh, Wed. January 28, 1998 Dr C Nicolson Dept. History, University of Stirling 1998 © Colin Nicolson 2 1 The future seemed bright for the English-born governor and onetime canon lawyer when, on a cold Saturday afternoon in February, 1763, Bostonians cheered as he walked out onto the small balcony of the Town House. He read aloud a brief statement, a royal proclamation, announcing that the long war with France was finally over. A “general Joy was difused thro’ all Ranks” of townspeople crammed into the streets below, reported one newspaper, before Francis Bernard politely took his leave of the crowd. Only for the most pessimistic of New Englanders were the signs ominous. Looking on was a brilliant civil and maritime lawyer who had astonished peers with his audacity to challenge in court the legality of a vital instrument of royal government. James Otis Jr. would often confound his admirers with his unpredictability and vivacious mind, but of one thing he had never been more certain: the war’s end promised to awaken dormant conflicts of interest between the king’s loyal American subjects and an imperial government in London unappreciative of the many sacrifices they had made in the struggle against the French and the Indians. Of particular concern to Otis was the role which royal officials like Bernard would play in Britain’s efforts to revitalise royal government. Bernard might invite the colonists to enjoy the benefits of empire, but his every word, his every step, seemed beguiling, and mindful of Britain’s hitherto postponed intention to reform the colonial system. -

The Muse of Fire: Liberty and War Songs As a Source of American History

3 7^ A'£?/</ THE MUSE OF FIRE: LIBERTY AND WAR SONGS AS A SOURCE OF AMERICAN HISTORY DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Kent Adam Bowman, B.A., M.A Denton, Texas August, 1984 Bowman, Kent Adam, The Muse of Fire; Liberty and War Songs as a Source of American History. Doctor of Philosophy (History), August, 1984, 337 pp., bibliography, 135 titles. The development of American liberty and war songs from a few themes during the pre-Revolutionary period to a distinct form of American popular music in the Civil War period reflects the growth of many aspects of American culture and thought. This study therefore treats as historical documents the songs published in newspapers, broadsides, and songbooks during the period from 1765 to 1865. Chapter One briefly summarizes the development of American popular music before 1765 and provides other introductory material. Chapter Two examines the origin and development of the first liberty-song themes in the period from 1765 to 1775. Chapters Three and Four cover songs written during the American Revolution. Chapter Three describes battle songs, emphasizing the use of humor, and Chapter Four examines the figures treated in the war song. Chapter Five covers the War of 1812, concentrating on the naval song, and describes the first use of dialect in the American war song. Chapter Six covers the Mexican War (1846-1848) and includes discussion of the aggressive American attitude toward the war as evidenced in song. -

A Journal of Political Thought and Statesmanship

VOLUME XVI, NUMBER 3, SUMMER 2016 A Journal of Political Thought and Statesmanship Michael Knox Richard Beran: Samuelson: Brexit and Hamilton All at on Broadway Patrick J. Garrity: David P. Henry Goldman: Kissinger Flailing Abroad Linda Bridges: e Comma Mark Queen Bauerlein: Queer eory Cheryl Miller: Jonathan Douglas Franzen Kries: Augustine’s Joseph Confessions Epstein: Isaiah Richard Berlin Talbert & Timothy W. Caspar: SPQR A Publication of the Claremont Institute PRICE: $6.95 IN CANADA: $8.95 Wealth, Poverty and Politics is a new approach to understanding age-old issues about economic disparities among nations and within nations. These disparities are examined in the light of history, economics, geography, demography and culture. Wealth, Poverty and Politics is also a challenge to much that is being said today about income distribution and wealth concentration— a challenge to the underlying assumptions and to the ambiguous words and misleading statistics in which those assumptions are embedded, often even by leading economists. This includes statistics about the much-discussed “top one percent.” This revised and enlarged edition should be especially valuable to those who teach, and who want to confront their students with more than one way of looking at issues that are too important to be settled by whatever the prevailing orthodoxy happens to be. A true gem in terms of exposing the demagoguery and sheer ignorance of politicians and intellectuals in their claims about wealth and poverty . Dr. Sowell’s new book tosses a monkey wrench into most of the things said about income by politicians, intellectuals and assorted hustlers, plus it’s a fun read.