Wisconsin Magazine of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHICAGO JEWISH HISTORY Spring Reviews & Summer Previews

Look to the rock from which you were hewn Vol. 41, No. 2, Spring 2017 1977 40 2017 chicago jewish historical societ y CHICAGO JEWISH HISTORY Spring Reviews & Summer Previews Sunday, August 6 “Chicago’s Jewish West Side” A New Bus Tour Guided by Jacob Kaplan and Patrick Steffes Co-founders of the popular website www.forgottenchicago.com Details and Reservation Form on Page 15 • CJHS Open Meeting, Sunday, April 30 — Sunday, August 13 Professor Michael Ebner presented an illustrated talk “How Jewish is Baseball?” Report on Page 6 A Lecture by Dr. Zev Eleff • CJHS Open Meeting, Sunday, May 21 — “Gridiron Gadfly? Mary Wisniewski read from her new biography Arnold Horween and of author Nelson Algren. Report on Page 7 • Chicago Metro History Fair Awards Ceremony, Jewish Brawn in Sunday, May 21 — CJHS Board Member Joan Protestant America” Pomaranc presented our Chicago Jewish History Award to Danny Rubin. Report on Page 4 Details on Page 11 2 Chicago Jewish History Spring 2017 Look to the rock from which you were hewn CO-PRESIDENT’S CO LUMN chicago jewish historical societ y The Special Meaning of Jewish Numbers: Part Two 2017 The Power of Seven Officers & Board of In honor of the Society's 40th anniversary, in the last Directors issue of Chicago Jewish History I wrote about the Jewish Dr. Rachelle Gold significance of the number 40. We found that it Jerold Levin expresses trial, renewal, growth, completion, and Co-Presidents wisdom—all relevant to the accomplishments of the Dr. Edward H. Mazur* Society. With meaningful numbers on our minds, Treasurer Janet Iltis Board member Herbert Eiseman, who recently Secretary completed his annual SAR-EL volunteer service in Dr. -

Gossip from Many Fields O

10 llltt TTMtfHi TmriiST.)AT, OCTOBMt 10, 1919 o Gossip From Many Fields o PENNSYLVANIA MAY SECURE PRESENT DAY FIGHTERS HAVE NO NEW KNOCKOUT ROBINSON, VETERAN COACH OF FOOTBALL TITLE THIS YEAR PUNCHES SUCH AS OLD TIMERS USED IN THE RING BROWN, IS FOOTBALL WIZARD Cont-l- i and Tram Has Made Provi- Folwell Has Many Stnrs Already --r -vr MM rr a Brings Out Good Teams Year After Year At Excellent on Attack Big JrrFftteS' Showing OCA LEFT-- dence Although He Very Often Starts Season Game Willi Pittsburgh. With Poor Material At Hand. New Oct. 1ft de- received honorable mention from York It may that 1(5- .- for the balance Walter in and is a Providence, Oct. Blue days for a month, and possibly velop in the course of current foot- Camp 1916, star BroTvn this week. The Harvard game of the season. He hasn't a chance oi ball the who ranks with Capt, Murray of on for and what little into the Harvard or Yale operations that snappiest Harvard. The backfleld tap Saturday getting ifl has terrific there is of the new team 13 wrecked- - games, and the best hope that he games of the will be played by Ben 190-pou- Da- year power, Derr, a The Colgate game last Saturday was may convalesce in time to Jump in Pennsylvania and Pittsburgh, on the kota boy, is fullback and a violent to broad reaches of Franklin Field in more than a defeat; it rates close a against Dartmouth. line cracker, as he has proved in disaster. -

Arda's Excellent Adventure

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 18, No. 6 (1996) ARDA'S EXCELLENT ADVENTURE Arda Bowser '23 Honored As "The Oldest Living Ex-NFL Player" At Tampa Stadium Game By Jim Campbell Arda Bowser passed away on September 7, 1996, in Winter Park, FL. at age 97. Two years earlier, in the NFL Film 75 Seasons, he was identified as the oldest living ex-NFL player. As it turned out, this wasn’t correct. Ralph Horween who played for the Chicago Cardinals in 1921-23 turned 100 in ‘96. Neither Bowser, the NFL, nor apparently any pro football historian realized Horween was still aliver. Though Bowser was not the oldest ex-player, the recognition he received was certainly deserved on many other counts. An outstanding player in his day, he remained alert and vigorous to the end. Jim Campbell wrote the following in 1994. When you are age 95, even though you were a football All-America at Bucknell and a member of your alma mater's Athletic Hall of Fame, you are very likely far removed from any sports spotlight. In the case of Arda Bowser '23, an All-East and All-America mention fullback and an accomplished kicker, the spot- light shown brightly recently (August 6) at an NFL preseason game at Tampa Stadium when the home- standing Buccaneers played the Cincinnati Bengals. Some time ago, Bowser, a retired insurance executive and resident of Florida since 1947, was brought to the attention of the NFL as its "oldest living `graduate.'" With the NFL embarking on its 75th season, suitable celebrations are in order. -

2005 USC Trojans Football Combined Team Statistics (As of Oct

2005 USC TROJANS GAME NOTES FOOTBALL SPORTS INFORMATION OFFICE • HER 103 • LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90089-0601 TELEPHONE: (213) 740-8480 FAX: (213) 740-7584 WWW.USCTROJANS.COM TIM TESSALONE, DIRECTOR FOR RELEASE: Oct. 2, 2005 2005 USC FOOTBALL SCHEDULE (4-0) TOP-RANKED, 2-TIME DEFENDING NATIONAL CHAMP USC FOOTBALL RETURNS HOME TO FACE ARIZONA DATE OPPONENT TIME/RESULT Sept. 3 at Hawaii W 63-17 Sept. 17 Arkansas W 70-17 FACTS Sept. 24 at Oregon W 45-13 USC (4-0 overall, 2-0 Pacific-10) vs. Arizona (1-3, 0-1), Saturday, Oct. 8, 12:30 p.m. PDT, Los Ange- Oct. 1 at Arizona State W 38-28 les Coliseum. Oct. 8 Arizona 12:30 p.m. (FSN) Oct. 15 at Notre Dame 2:30 p.m. (NBC) THEMES Oct. 22 at Washington TBA After a pair of tough comeback road wins, top-ranked USC makes a brief return to the friendly Oct. 29 Washington State 12:30 p.m. (ABC) Coliseum to face Arizona before hitting the road for 2 more contests. The Trojans hope to Nov. 5 Stanford TBA extend a number of winning streaks: a Pac-10 record 26 overall games, a school-record 22 Nov. 12 at California TBA home games and a league-record 15 Pac-10 home games, as well as 17 overall Pac-10 games. Nov. 19 Fresno State 7:15 p.m. (FSN) The Wildcats were the last team to beat a No. 1-ranked USC squad, pulling off a 3-point upset Dec. 3 UCLA 1:30 p.m. -

Forever Young Homicide Investigation at Temescal Canyon

Palisadian-Post Serving the Community Since 1928 20 Pages Thursday, July 26, 2018 ◆ Pacific Palisades, California $1.50 Forever Young Homicide Investigation at Temescal Canyon LAPD addresses the press. Rich Schmitt/Staff Photographer By TRILBY BERESFORD be associated with any gangs. Reporter Radtke confirmed that an au- topsy is pending with the Los An- t approximately 1:30 p.m. on geles Medical Coroner to determine Saturday, July 21, a deceased the cause of death. Amale of Guatemalan decent was LAPD are in possession of two found in heavy brush off Temes- photos of the victim from “prior po- cal Canyon Road between Pacif- lice contact.” It appears that a small ic Coast Highway and Bowdoin face tattoo is visible on the more Street. recent of the two photos. A local resident discovered the “This new tattoo could possi- body and alerted passersby, who bly be a teardrop,” Radtke said. Theatre Palisades Youth, featuring 40 local actors ages 8 to 14, presents “Peter Pan Jr.” at Pierson Playhouse. The nine-performance called the Los Angeles Police De- To conclude the conference, show runs July 27 through Aug. 5. For tickets and show times, visit theatrepalisades.com. Rich Schmitt/Staff Photographer partment. Radtke noted that Pacific Palisades Officers arrived in multiple is not a high crime area. vehicles and closed off the road in “This is the first homicide in quest for comment before going both directions pending their inves- the West Los Angeles area all year to print, has not budged on any tigation. long,” he said. PPRA Files Lawsuit Against design or infrastructure changes “The victim was found with a Authorities have yet to release to appease the many neighbors stab wound and pronounced dead the name of the deceased, and and Palisadians who oppose the at the scene,” LAPD Officer Drake Radtke emphasized that they know City of LA, Coastal Commission project based on characteristics Madison told the Palisadian-Post very little about his history in re- like view-blocking heights and during an initial phone call. -

2004 USC Trojans Football USC Trojans Combined Team Statistics (As of Sep 11, 2004) All Games

2004 USC TROJANS GAME NOTES FOOTBALL SPORTS INFORMATION OFFICE • HER 103 • LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90089-0601 TELEPHONE: (213) 740-8480 FAX: (213) 740-7584 WWW.USCTROJANS.COM TIM TESSALONE, DIRECTOR FOR RELEASE: Sept. 13, 2004 2004 USC FOOTBALL SCHEDULE (2-0) NO. 1-RANKED USC FOOTBALL MAKES FIRST-EVER VISIT TO BYU DATE OPPONENT TIME/RESULT FACTS Aug. 28 vs. Virginia Tech W 24-13 Sept. 11 Colorado State W 49-0 USC (2-0 overall) vs. BYU (1-1), Saturday, Sept. 18, 8 p.m. MST/7 p.m.PDT, LaVell Edwards Sta- Sept. 18 at BYU 8 p.m. (ESPN) dium, Provo, Ut. Sept. 25 at Stanford 4 p.m. (TBS) Oct. 9 California TBA THEMES Oct. 16 Arizona State TBA Top-ranked and defending national champion USC puts its 11-game winning streak on the line Oct. 23 Washington TBA when it makes its first-ever visit to BYU this week. It’s just the second meeting between the Oct. 30 at Washington State 4 p.m. (ABC) Trojans and Cougars, following last year’s closer-than-the-final-score USC victory. It’s been 87 Nov. 6 at Oregon State TBA years since the Trojans have played a football game in the state of Utah. It should be a difficult Nov. 13 Arizona 7:15 p.m. (FSN) environment for Troy, as 64,045-seat LaVell Edwards Stadium could be at capacity. It’ll be a Nov. 27 Notre Dame 5 p.m. (ABC) homecoming for USC offensive coordinator Norm Chow, who returns for the first time to the Dec. -

Football on P Basis Teenth

THE STJtf, SUNDAY, SEPl'EMBER 21, S 8 Football Is in forIts GreatestYear 1919 CampaignWiU Be Launched onGtidirons ThroiighoutCountry Next Saturday BEST YEAR OF ALL Upstate and Local Captain. BROOKS SELECTS VARSITY. FOOTBALL TREATS SCHEDULES OF LEADERS IN HARVARD SQUAD IS Football Conch Chooses Men for COLLEGE FOOTBALL CIRCLES FOR KIM FOOTBALL First Team. OH LOCAL FIELDS CUT BY COACHES ftpedal Dfpatch to Tns Scs. Ilariard ' , Torh at Pltlsburg: Novwnbor 1. Pittsburg WitxiAMSTOWN, Sept. 20. Coach Oc-- at South Bethlehem: 8, Pemn State at State September 27, Ratis at Cambridge: Dethlo-hem- o team, A. College; 16, Muhlonburg at South Brooks of the Williams football tober Tlndnn fvilliu. r?AtnLrldffO! 11. 22, Lafayette South Bethlehem. se- Colby at Oambrldgo; 18. Drown Cam- at after two weeks of practice, has -at of Stnrs From" Scrvico Army vs. Navy, Dartmouth vs. j bridge; 25, Cambridge- Novcm- - ' Fisher Has Jinny Star Backs, Return lected a tentative varsity, and an oppor- Virginia at . Trinity on the '.',i'"D8Uid at famDriage: o. Standard in1 Age, tunity Is offered to get a line Penn. and Syracuse vs. Rut- t I'rlncolon; 10, Tufts at Cambridge;" 22, October 4, Princeton at rrlnceton; 11, Imt Must Search Candidates Baiscs makeup of tho Purplo eleven this fall. .nm at iamDrldgo. Connecticut Aggies at Hartford; 18. Am- 26, Poly at Seven veterans are Included on the - herst at Amherst; Worcester yciglit and Experience. gers on Polo Grounds. rrlnceton Hartford: November 4, New YorkwUnl-verelt- y for Lino Material. squad which appears to be most promis- at New York: 16. Lafayette at ing. -

2005 USC FOOTBALL NOTES DATE OPPONENT TIME Sept

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS • HER 103 • LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90089-0601 TELEPHONE: (213) 740-8480 FAX: (213) 740-7584 SPORTS INFORMATION OFFICE FOR RELEASE: Aug. 2, 2005 TIM TESSALONE, DIRECTOR 2005 SCHEDULE 2005 USC FOOTBALL NOTES DATE OPPONENT TIME Sept. 3 at Hawaii 1 p.m. (ESPN2) PRE-SEASON RANKINGS… Sept. 17 Arkansas 7:15 p.m. (FSN) The two-time defending national champion 2005 Trojans are the clear favorite to win the Sept. 24 at Oregon 4 p.m. (ABC) national title again, according to various pre-season prognosticators. Here’s a look: Oct. 1 at Arizona State TBA Oct. 8 Arizona TBA National Pacific-10 Oct. 15 at Notre Dame 2:30 p.m. (NBC) Athlon 1st 1st Oct. 22 at Washington TBA The Sporting News 1st 1st Oct. 29 Washington State 12:30 p.m. (ABC) Street & Smith’s 1st 1st Nov. 5 Stanford TBA Phil Steele’s 1st 1st Nov. 12 at California TBA Lindy’s 1st 1st Nov. 19 Fresno State 7:15 p.m. (FSN) Blue Ribbon 1st 1st Dec. 3 UCLA 1:30 p.m. (ABC) Gold Sheet 1st 1st 2004 RESULTS …AND PRE-SEASON HONORS st (13-0 overall, 8-0 for 1 place in Pac-10) QB Matt Leinart (Playboy, Athlon, The Sporting News, Street & Smith’s, Phil Steele’s, Lindy’s, 24 vs. Virginia Tech 13 Blue Ribbon), TB Reggie Bush (Playboy, Athlon, The Sporting News, Street & Smith’s, Phil (at Landover, Md.) Steele’s, Lindy’s, Blue Ribbon), S Darnell Bing (The Sporting News, Street & Smith’s, Phil 49 Colorado State 0 Steele’s), P Tom Malone (Playboy, Phil Steele’s) and WR Dwayne Jarrett (Athlon) have been 42 at BYU 10 named to various pre-season All-American first teams. -

Coffin Corner Index

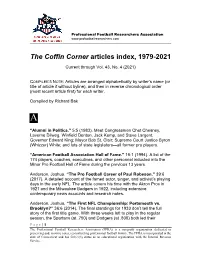

Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com The Coffin Corner articles index, 1979-2021 Current through Vol. 43, No. 4 (2021) COMPILER’S NOTE: Articles are arranged alphabetically by writer’s name (or title of article if without byline), and then in reverse chronological order (most recent article first) for each writer. Compiled by Richard Bak A “Alumni in Politics.” 5:5 (1983). Meet Congressmen Chet Chesney, Laverne Dilweg, Winfield Denton, Jack Kemp, and Steve Largent; Governor Edward King; Mayor Bob St. Clair; Supreme Court Justice Byron (Whizzer) White; and lots of state legislators—all former pro players. “American Football Association Hall of Fame.” 16:1 (1994). A list of the 174 players, coaches, executives, and other personnel inducted into the Minor Pro Football Hall of Fame during the previous 13 years. Anderson, Joshua. “The Pro Football Career of Paul Robeson.” 39:6 (2017). A detailed account of the famed actor, singer, and activist’s playing days in the early NFL. The article covers his time with the Akron Pros in 1921 and the Milwaukee Badgers in 1922, including extensive contemporary news accounts and research notes. Anderson, Joshua. “The First NFL Championship: Portsmouth vs. Brooklyn?” 36:6 (2014). The final standings for 1933 don’t tell the full story of the first title game. With three weeks left to play in the regular season, the Spartans (at .750) and Dodgers (at .800) both led their P a g e | 1 The Professional Football Researchers Association (PFRA) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving and, in some cases, reconstructing professional football history. -

2004 USC Trojans Football-- USC Trojans Combined Team Statistics (As of Dec

2004 USC TROJANS GAME NOTES FOOTBALL SPORTS INFORMATION OFFICE • HER 103 • LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90089-0601 TELEPHONE: (213) 740-8480 FAX: (213) 740-7584 WWW.USCTROJANS.COM TIM TESSALONE, DIRECTOR FOR RELEASE: Dec. 20, 2004 2004 USC FOOTBALL SCHEDULE (12-0) NO. 1 USC MEETS NO. 2 OKLAHOMA IN ORANGE BOWL BCS CHAMPIONSHIP GAME DATE OPPONENT TIME/RESULT FACTS Aug. 28 vs. Virginia Tech W 24-13 USC (12-0 overall, 8-0 Pac-10) vs. Oklahoma (12-0, 8-0 Big 12), BCS Championship Game, FedEx Sept. 11 Colorado State W 49-0 Orange Bowl, Tuesday, Jan. 4, 8:20 p.m. EST/5:20 p.m. PST, Pro Player Stadium, Miami, Fla. Sept. 18 at BYU W 42-10 Sept. 25 at Stanford W 31-28 THEMES Oct. 9 California W 23-17 What a high-powered, star-studded match-up this BCS Championship Game in the 2005 Or- Oct. 16 Arizona State W 45-7 ange Bowl will be: top-ranked and defending national champion USC versus No. 2 Oklahoma, Oct. 23 Washington W 38-0 which played in last year’s BCS contest. It’s a meeting of 2 of college football’s most historic Oct. 30 at Washington State W 42-12 programs. These teams have met just 8 times, and it’s been a dozen years since the last faceoff. Nov. 6 at Oregon State W 28-20 Each USC-OU game has featured a ranked team…and oftentimes a highly-ranked team. In Nov. 13 Arizona W 49-9 fact, it’s not the first time the No. -

BINGO! Ury Morgenthau Termed “A New Instead of Going out of Town

V::i (-■'': «■ ■ - !0 5 r»T?r.^ ^4jWXvv*" ' V -* -.7 TMtwnlty lUrehM On” !•. the A daughter was bom Friday at T to monthly meeting ot the Msa- nrflUtcMHiiMt/ W win go to this morohsat The title ott ft tftUclDfUUcinc picture< that Ift to the Hartford hospital to Mr. and chaster Mastersstar IBsrberF Association, priie winner will receive, from the ’ 1 « A r lx ehowa Saturday evAilnf at 0:1s Mia. John McKenna o t Oakland paotpoaed from last Monday, will be club, on order for the amount of TfflOTHT d fiiiD w «s j r f l m f l l m l O r O f t d n Tinker ball under the au^oee of street. held tonlgtat at 8 o'clock tn Paganl'a money taken in at the Uet game. caUoq aqnivalaBt to four years cf " " " w iv B w e w Mancheetar Lodge, Loyal Order of Shop on Pearl street. A report on MDSC FEUOVmiP high aBheol and present rerommen- “MUMS” Friday. 06t, !• Mooaa. Xnvttatlona to the abowtng Rev. Nathaniel Carison and his the laws governing barber shops. The bond Idea is also well thought dattooa from fionner musle teochen bare been aent to many in town. daiightsr. Mias /lolet Oaiiscn, ot With partloular attention as to the out. Each game vrlnner, tn addi or achoolo. The Season's Snutft Way Osmelng fff>m 8 to U. There win be no charge made for Kansas, wiU present a boneert of tn- ekMlag hours, win be explain^ at tion to the regular prlw played for, Wins Gradoats Stady Coarac To Say It With Flowers Admiaalon ase. -

Bernie Mccarty

PAGE 6 BERNIE MCCARTY The College Football Historical Society, and the sport of football itself, recently suffered a major loss with the passing of Bernie McCarty, one of the game’s most prominent historians, on June 13, 1997. Mr McCarty was born in Chicago on October 7, 1933, one of three children: and spent much of his youthful days growing up in the town of Argo, Illinois; an industrial community located just south-west of the Chicago city limits. While attending Argo High School, Bernie quickly discovered his considerable interest in art and drawing. But eclipsing even his inclinations toward art, was his fanatical interest from an early age, in the sport of college football. Bernie often said that the first college game he had ever seen on television was the famous 1949 Notre Dame vs Southern Methodist battle which always remained as one of his personal favorites of all-time. Before long the budding sports historian, while still at Argo High, was spending every possible free moment poring over the old newspaper files at the Chicago Public Library. These were still the days before the common use of microfilm and Bernie was quickly captured by the pleasures that every true historian experiences when confronted by the original newspapers of long ago. Throughout the rest of his life Bernie was a staunch contender of the point that, the newspapers of long ago are the only true source for any type of serious sports historical research. In fact, Bernie was spending so much time at the Chicago Library that he became friends with the newspaper room librarians; who eventually gave the young man access to even the oldest of newspaper files, which were usually kept secured from the general public.