Turkey Indictment Project Final Report 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reports on Human Rights Issues

About Stockholm Center for Freedom Stockholm Center for Freedom (SCF) is a non-profit advocacy organization that promotes the rule of law, democracy and human rights with a special focus on Turkey. SCF was set up by a group of journalists who have been forced to live in self-exile in Sweden against the backdrop of a massive crackdown on press freedom in Turkey. SCF is committed to serving as a reference source by providing a broader picture of rights violations in Turkey, monitoring daily developments, documenting individual cases of the infringement of fundamental rights and publishing comprehensive reports on human rights issues. SCF is a member of the Alliance Against Genocide, an international coalition dedicated to creating the international institutions and the political will to prevent genocide. 1 Contents* 1. Introduction 3 2. Crackdown on the Gülen movement 4 3. Crackdown on the Kurdish political movement 20 4. Minority and refugee rights 24 5. Press freedom 29 6. Torture and inhuman treatment 34 7. Women’s rights 39 * Subject matters are listed in alphabetical order 2 1. Introduction This report highlights the most important developments in the area of human rights in Turkey during the year 2020. Rising pressure on the Kurdish political movement, the crackdown on the Gülen movement, the arrest of journalists and deteriorating press freedom, the spread of hate speech and hate crimes targeting ethnic and religious minorities and refugees, systematic torture and ill-treatment and an increase in rights violations against women were the defining topics of the year. Turkey has been experiencing a deepening human rights crisis over the past seven years. -

NETHERLANDS HELSINKI COMMITTEE Riviervismarkt 4 2513 AM the Hague Netherlands +31 (0) 70 392 67 00 [email protected]

Currently we find ourselves in an environment in Turkey where international human rights and constitutional regulations are violated every day. This also directly affects the right of defence, one of the right to fundamental principles of the right to a fair trial. In recent years, emergency decrees, issued during the State of Emergency period (following the 2016 coup attempt), have continued to be applied or were eventually enacted into law. A consequence of this is the gradual shrinking of space for defence to the point of its near complete removal, despite it being one of the founding elements of justice. Increasingly, lawyers began to be accused and convicted for being ‘members of terrorist organisations,’ especially in connection to the defendants they defended. A DEFENSELESS DEFENSE AUTHOR Faruk Eren (Except for the Foreword and the Introduction) TRANSLATOR Sebastian Heuer DESIGN BEK HAFIZA MERKEZİ Ömer Avni Mahallesi İnönü Caddesi Akar Palas No:14 Kat:1 Beyoğlu 34427 Istanbul TR +90 212 243 32 27 [email protected] www.hafiza-merkezi.org A DEFENSELESS ASSOCIATION FOR MONITORING EQUAL RIGHTS (AMER) Gümüşsuyu, Ağa Çırağı Sk. Pamir Apt. No:7/1, DEFENSE Beyoğlu 34437 İstanbul +90 212 293 63 77 – 0501 212 72 77 [email protected] [email protected] www.esithaklar.org NETHERLANDS HELSINKI COMMITTEE Riviervismarkt 4 2513 AM The Hague Netherlands +31 (0) 70 392 67 00 [email protected] www.nhc.nl With The Contribution of: LAWYERS FOR LAWYERS Nieuwe Achtergracht 164 1018 WV Amsterdam Netherlands +31(0) 20 717 16 38 [email protected] www.lawyersforlawyers.org FOREWORD This report was prepared within the scope of a joint project by the Association for Monitoring Equal Rights (Eşit Haklar İçin İzleme Derneği – EŞHİD), Netherlands Helsinki Committee (NHC) and Truth Justice Memory Center (Hafıza Merkezi), which aims to increase support for human rights defenders (HRDs) in Turkey. -

Newsletter Focuses on Issues Relating to Historical Dialogue, Historical and Transitional Justice, and Public and Social Memory

December 3, 2018 Our newsletter focuses on issues relating to historical dialogue, historical and transitional justice, and public and social memory. More details about items in ournewsletter (and more!) can be found on our website. Both our website and newsletter provide information and resources to encourage innovative interdisciplinary, transnational and comparative research. They are housed at the Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University, New York City. The Network is devoting its blog space in this issue to condemn the arrests of 13 activists in Turkey, among them AHDA alumna Asena Gunal, and longtime friend of the AHDA program, Meltem Aslan, for their links to activist and philanthropist Osman Kavala. While they have been released, these activists' detention points to the alarming and continued attacks on civil society organizations and on voices that are critical of the Turkish government. It is, as the European Parliament's Turkey rapporteur Kati Piri writes, "another brutal assault on Turkish civil society." The below photograph and article were published on Nov.16, 2018, by Amnesty International; readers can also find coverage in the Washington Post; Reuters; Radio Free Europe; and elsewhere. Osman Kavala has now been imprisoned for approximately 13 months without being charged. Turkey: Brutal crackdown continues with new wave of activist arrests “Osman Kavala and all those detained today must be immediately and unconditionally released, and the crackdown against Turkey’s independent civil society must be brought to an end” - Andrew Gardner Turkish authorities have today detained 13 activists in connection with the investigation into jailed human rights defender Osman Kavala. -

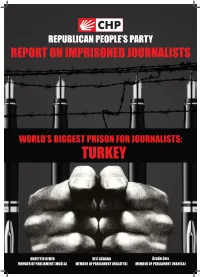

Report on Imprisoned Journalists

REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY REPORT ON IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS WORLD’S BIGGEST PRISON FOR JOURNALISTS: TURKEY NURETTİN DEMİR VELİ AĞBABA ÖZGÜR ÖZEL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MUĞLA) MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MALATYA) MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MANİSA) REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY PRISON EXAMINATION AND WATCH COMMISSION REPORT ON IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS WORLD’S BIGGEST PRISON FOR JOURNALISTS: TURKEY NURETTİN DEMİR VELİ AĞBABA ÖZGÜR ÖZEL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MUĞLA) (MALATYA) (MANİSA) CONTENTS PREFACE, Ercan İPEKÇİ, General Chairman of the Union of Journalists in Turkey ....... 3 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 11 2. JOURNALISTS IN PRISON: OBSERVATIONS AND FINDINGS .................. 17 3. JOURNALISTS IN PRISON .......................................................................... 21 3.1 Journalists Put on Trial on Charges of Committing an Off ence against the State and Currently Imprisoned ................................................................................ 21 3.1.1Information on a Number of Arrested/Sentenced Journalists and Findings on the Reasons for their Arrest ........................................................................ 21 3.2 Journalists Put on Trial in Association with KCK (Union of Kurdistan Communities) and Currently Imprisoned .................................... 32 3.2.1Information on a Number of Arrested/Sentenced Journalists and Findings on the Reasons for their Arrest ....................................................................... -

Executive Technique in the Civil Process Code and Its Limits

EXECUTIVE TECHNIQUE IN THE CIVIL PROCESS . 2020 . pr ./A CODE AND ITS LIMITS an A TÉCNICA EXECUTIVA NO CÓDIGO DE PROCESSO CIVIL E SEUS LIMITES . 342-367 • J . 342-367 p .1 • .1 MATEUS SCHWETTER SILVA TEIXEIRA1 n .15 • .15 v ABSTRACT This article deals with the execution of Brazilian civil procedural law and its evolution. With the Civil Proce- dure Code of 2015, there have been changes and innovations in numerous articles, such as article 139, item IV, which generated understanding of part of the doctrine of the atypicality of executive means in execution for certain amount, with the application of measures atypical to those debtors, such as the retention of the passport or the national driver’s license. It is around this theme that the present work will be developed. The methodology used was a qualitative research, with a review of the literature on the topic, within classic and modern doctrines, as well as legal articles and current jurisprudence. In the first stage, we observe the MERITUM MAGAZINE • general aspects of the execution process. The second stage deals with the application of executive means, from the original Civil Procedure Code of 1973, the reforms of 1994 and 2002 and the new code of 2015, with an analysis of Article 139, item IV, and their possible effects. In the third step, we intend a constitutional analysis of the effects of the application of article 139, section IV of said Code. In the end, the possibility of applying the measures will be demonstrated, according to requirements that must be observed by the judge. -

Nedim Sener Group of Cases V. Turkey (Application No

SECRETARIAT / SECRÉTARIAT SECRETARIAT OF THE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS SECRÉTARIAT DU COMITÉ DES MINISTRES Contact: John Darcy Tel: 03 88 41 31 56 Date: 27/02/2020 DH-DD(2020)187 Document distributed under the sole responsibility of its author, without prejudice to the legal or political position of the Committee of Ministers. Meeting: 1369th meeting (March 2020) (DH) Communication from an NGO (Amnesty International) (19/02/2020) and reply from the authorities (27/02/2020) in the Nedim Sener group of cases v. Turkey (Application No. 38270/11) Information made available under Rules 9.2 and 9.6 of the Rules of the Committee of Ministers for the supervision of the execution of judgments and of the terms of friendly settlements. * * * * * * * * * * * Document distribué sous la seule responsabilité de son auteur, sans préjuger de la position juridique ou politique du Comité des Ministres. Réunion : 1369e réunion (mars 2020) (DH) Communication d’une ONG (Amnesty International) (19/02/2020) et réponse des autorités (27/02/2020) relative au groupe d’affaires Nedim Sener c. Turquie (requête n° 38270/11) [anglais uniquement] Informations mises à disposition en vertu des Règles 9.2 et 9.6 des Règles du Comité des Ministres pour la surveillance de l’exécution des arrêts et des termes des règlements amiables. DH-DD(2020)187: Rule 9.2 Communication from an NGO in Nedim Sener group v. Turkey. Document distributed under the sole responsibility of its author, without prejudice to the legal or political position of the Committee of Ministers. DGI 19 FEV. 2020 SERVICE DE L’EXECUTION DES ARRETS DE LA CEDH SUBMISSION TO THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS: NEDIM SENER V. -

Reexamining the Seventh Amendment Argument Against Issue Certification

Pace Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Summer 2014 Article 2 July 2014 Reexamining the Seventh Amendment Argument Against Issue Certification Douglas McNamara George Washington University Law School Blake Boghosian George Washington University Law School Leila Aminpour Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr Part of the Civil Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Douglas McNamara, Blake Boghosian, and Leila Aminpour, Reexamining the Seventh Amendment Argument Against Issue Certification, 34 Pace L. Rev. 1041 (2014) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol34/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reexamining the Seventh Amendment Argument Against Issue Certification D. McNamara, * B. Boghosian** & L. Aminpour*** I. Introduction Issue certification is a controversial means of handling aggregate claims in Federal Courts. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure (“FRCP”) 23(c)(4) provides that “[w]hen appropriate, an action may be brought or maintained as a class action with respect to particular issues.”1 Issue certification has returned to the radar screen of academics,2 class action counsel,3 and defendants.4 The Supreme Court’s decision regarding the need for viable damage distribution models in Comcast v. Behrend5 may spur class counsel in complex cases to bifurcate liability and damages. * Douglas McNamara is Of Counsel at Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll, PLLC, in Washington, D.C. He is an adjunct faculty member of George Washington University Law School and has practiced sixteen years in the area of complex civil litigation and class actions. -

Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 414 September 2019

INSTITUT KURDDE PARIS E Information and liaison bulletin N° 414 SEPTEMBER 2019 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Ministry of Culture This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 414 September 2019 • TURKEY: DESPITE SOME ACQUITTALS, STILL MASS CONVICTIONS.... • TURKEY: MANY DEMONSTRATIONS AFTER FURTHER DISMISSALS OF HDP MAYORS • ROJAVA: TURKEY CONTINUES ITS THREATS • IRAQ: A CONSTITUTION FOR THE KURDISTAN REGION? • IRAN: HIGHLY CONTESTED, THE REGIME IS AGAIN STEPPING UP ITS REPRESSION TURKEY: DESPITE SOME ACQUITTALS, STILL MASS CONVICTIONS.... he Turkish govern- economist. The vice-president of ten points lower than the previ- ment is increasingly the CHP, Aykut Erdoğdu, ous year, with the disagreement embarrassed by the recalled that the Istanbul rate rising from 38 to 48%. On economic situation. Chamber of Commerce had esti- 16, TurkStat published unem- T The TurkStat Statistical mated annual inflation at ployment figures for June: 13%, Institute reported on 2 22.55%. The figure of the trade up 2.8%, or 4,253,000 unem- September that production in the union Türk-İş is almost identical. ployed. For young people aged previous quarter fell by 1.5% HDP MP Garo Paylan ironically 15 to 24, it is 24.8%, an increase compared to the same period in said: “Mr. -

Identity, Interest, and Politics

INTERNATIONAL MAX PLANCK RESEARCH SCHOOL on the Social and Political Constitution of the Economy Köln, Germany Azer Kiliç Identity, Interest, and Politics The Rise of Kurdish Associational Activism and the Contestation of the State in Turkey Studies on the Social and Political Constitution of the Economy Azer Kiliç Identity, Interest, and Politics The Rise of Kurdish Associational Activism and the Contestation of the State in Turkey © Azer Kiliç, 2013 Published by IMPRS-SPCE International Max Planck Research School on the Social and Political Constitution of the Economy, Cologne http://imprs.mpifg.de ISBN: 978-3-946416-03-6 DOI: 10.17617/2.1857884 Studies on the Social and Political Constitution of the Economy are published online on http://imprs.mpifg.de. Go to Dissertation Series. Studies on the Social and Political Constitution of the Economy Abstract This dissertation investigates associational behaviour in a context of eth- nic conflict and contestation of the state. With a case study of the Kurd- ish issue in Turkey, it examines the position of interest associations in the major Kurdish province of Diyarbakır in relation to political struggles be- tween different models of social integration by exploring the relative weight of economic interests and collective identity politics in influencing associational strategies. This examination draws on the theoretical litera- ture on interest associations and their impact on social order and democ- racy. In particular, the analysis adopts the framework of Streeck and Schmitter to understand the logic of associational action by looking at the environments of membership and influence. The analysis, however, modifies this framework by emphasizing the duality seen within both en- vironments, as well as the transitional context that the contestation of the state and socio-economic changes contribute to. -

Turkey: Freedom of Expression in Jeopardy Violations of the Rights of Authors, Publishers and Academics Under the State of Emergency

TURKEY: FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN JEOPARDY VIOLATIONS OF THE RIGHTS OF AUTHORS, PUBLISHERS AND ACADEMICS UNDER THE STATE OF EMERGENCY Yaman Akdeniz & Kerem Altıparmak ABOUT THE AUTHORS Prof. Dr. Yaman Akdeniz is a faculty member at Istanbul Bilgi University School of Law and has published extensively in the field of human rights and the Internet. In addition to numerous internationally acclaimed articles, he is the author of Internet Child Pornography and the Law: National and International Responses published by Ashgate in June 2008, Racism on the Internet published by the Council of Europe in 2010, Freedom of Expression on the Internet published by the OCSE in 2011 and Media Freedom on the Internet: An OSCE Guidebook commissioned by the Office of the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media and published in 2016. Assistant Professor Kerem Altıparmak is a faculty member at Ankara University Faculty of Political Sciences and has published extensively in the field of human rights and the Internet. Altıparmak is Director of the Human Rights Centre in the same faculty and is a human rights defender working in active partnership with civil society organisations. In addition to his numerous articles, Altıparmak is the author of the books The European Court of Human Rights 50 Years On: Success or Disappointment? (2009), Common Sense in Preventing Torture: An Evaluation of the Optional Protocol and Practice of Country Visits to Turkey (2008, with Hülya Üçpınar), Time and Its Limitations: Lifting the Shield for Grave Human Rights Violations (2016), and the Handbook on Combating Impunity (2016). Akdeniz and Altıparmak have co-authored the book Internet: Restricted Access, A Critical Assessment of Internet Content Regulation and Censorship in Turkey, published by İmaj Yayınları in 2008. -

Osman Kavala & Others V Turkey

TRIAL OBSERVATION REPORT Osman Kavala & others v Turkey Gezi Park, civil society and rights activists on trial February 2020 Published May 2020. Updated September 2020. Written by Kevin Dent QC Member, Bar Human Rights Committee Bar Human Rights Committee of England and Wales 289-293 High Holborn London WC1V 7HZ www.barhumanrights.org.uk Produced by BHRC Copyright 2020© BHRC Osman Kavala & others v Turkey Trial Observation Report 2 Table of Contents About the Bar Human Rights Committee .................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 Terms of Reference, Funding and Acknowledgements .................................................... 10 Previous Trial Observations in Turkey .................................................................................... 10 Context .................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Background: The Gezi Park events............................................................................................. 11 The ‘Taksim Solidarity’ trial .......................................................................................................... 12 The origin of the Gezi Park proceedings and use of pre-trial detention .................. 13 The Gezi Park indictment............................................................................................................... -

Cumhuriyet □Fuann Konuklan

Cumhuriyet □Fuann Konuklan.............................. ........................... 20-21. sayfalarda □ Fuar etkinlik programı 36-37-38. sayfalarda □ Fuara katılan yayınevleri - imza günleri 44-43. sayfalarda □Okurlarımızın fuarı ücretsiz geze bilmeleri için giriş davetiyesi............. ...................................... 43. s ay fada CUMHURİYET KİTAP SAYI 455 Yetmiş beş yılın en önemli yetmiş beş kitabı... • Federico García Lorca: 100. yaşında en yeni şiirleriyle... Yapı Kredi Yayınları V Uç Aylık Edebiyat Dergisi V ISSN 1300-0586 Sayı 34/Güz 1998 • Mîna Urgan: 75 Yıla Mührünü Vuran 75 Kitap kitap-hk'tan Büyük Anket Bir Dinozorun Anıları’na 9S0.000 TL “Küçük Mutluluklarda devam ediyor! Söyleşiler: • İlhan Berk: Hulki Aktunç "Gerçek Bir Neşâtî’ye yeniden Okurla Her Karşılaştığımda Bütün Yazdıklarımı Yeniden ses veriyor. Okuyorum" Sidney Wade - Padgett Povvell • Walter Feldman: "Türkiye Bana Esin Veriyor" Saatleri Ayarlama Federico García Lorca: 100 Enstitüsü’ne kuramsal yaşında en yeni şiirleriyle- . Mîna Urgan: Bir Dinozorun bir bakış. Arvlan 'oa "Küçük M utluluklar "la devam ediyor! İlhan Berk: Neşâtr 'ye yeniden ses • Pascal Quignard: v e riy o r. Deneme türünde Türkçeye Walter Feldman: Saatleri Ayarlama Enstitüsü" ne k u ra m sa l ilk kez konuk oluyor. b ir b a k ış . Pascal Quignard: D enem e türünde Türkçeye ilk kez konuk • Guy Davenport: o lu y o r. Guy Davenport Bronz, Ktrrraı “Bronz, Kırmızı Yapraklarda Yapraklarla Türkçede ilk kez. Türkçede ilk kez. Dosya: Sürgün SÖYLEŞİ: Hulki Aktunç - “Gerçek Bir Okurla Her Karşılaştığımda Bütün Yazdıklarımı Yeniden Okuyorum", Sidney Wade, Padgett Powetl- “Türkiye Bana Esin Veriyor”, Neşâtî - ilhan Berk - Gazeller, Süreyya Berfe - Çok Arıyorum Seni, Şavkar Altınel - Dingin Cumhuriyet, AH Cengizkan - “Hindistan’ın Kokusu”, Lale Müldür - Yaban, Nazmi Ağıl - Konuşulmayan, Samih Rifat - Federico García Lorca’nın Yeni Şiirleri, Federico Garda Lorca - Panayır,Craig Raine - Arınma, Vüs’af O.