A History of Jefferson County, Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State of Texas § City of Brownsville § County of Cameron §

THE STATE OF TEXAS § CITY OF BROWNSVILLE § COUNTY OF CAMERON § Derek Benavides, Secretary Abraham Galonsky, Commissioner Troy Whittemore, Commissioner Aaron Rendon, Commissioner Ruben O’Bell, Commissioner Vanessa Castillo, Commissioner Ronald Mills, Chairman NOTICE OF A PUBLIC MEETING OF THE PLANNING AND ZONING COMMISSION OF THE CITY OF BROWNSVILLE TELECONFERENCE OPEN MEETING Pursuant to Chapter 551, Title 5 of the Texas Government Code, the Texas Open Meetings Act, notice is hereby given that the Planning and Zoning Commission of the City of Brownsville, Texas, has scheduled a Regular Meeting on Thursday, April 1, 2021 at 5:30 P.M. via Zoom Teleconference Meeting by logging on at: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81044265311?pwd=YXZJcWhpdWNvbXNxYjZ5NzZEWUgrZz09 Meeting ID: 810 4426 5311 Passcode: 659924 This Notice and Meeting Agenda, are posted online at: http://www.cob.us/AgendaCenter The members of the public wishing to participate in the meeting hosted through WebEx Teleconference can join at the following numbers: One tap mobile: +13462487799,,81044265311#,,,,*659924# US (Houston) +16699006833,,81044265311#,,,,*659924# US (San Jose) Or Telephone: Dial by your location: +1 346 248 7799 US (Houston) +1 669 900 6833 US (San Jose) +1 253 215 8782 US (Tacoma) +1 312 626 6799 US (Chicago) +1 929 205 6099 US (New York) +1 301 715 8592 US (Washington DC) Meeting ID: 810 4426 5311 Passcode: 659924 Find your local number: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kbgc6tOoRF Members of the public who submitted a “Public Comment Form” will be permitted to offer public comments as provided by the agenda and as permitted by the presiding officer during the meeting. -

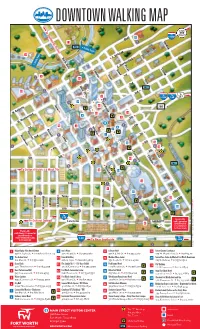

Downtown Walking Map

DOWNTOWN WALKING MAP To To121/ DFW Stockyards District To Airport 26 I-35W Bluff 17 Harding MC ★ Trinity Trails 31 Elm North Main ➤ E. Belknap ➤ Trinity Trails ★ Pecan E. Weatherford Crump Calhoun Grov Jones e 1 1st ➤ 25 Terry 2nd Main St. MC 24 ➤ 3rd To To To 11 I-35W I-30 287 ➤ ➤ 21 Commerce ➤ 4th Taylor 22 B 280 ➤ ➤ W. Belknap 23 18 9 ➤ 4 5th W. Weatherford 13 ➤ 3 Houston 8 6th 1st Burnett 7 Florence ➤ Henderson Lamar ➤ 2 7th 2nd B 20 ➤ 8th 15 3rd 16 ➤ 4th B ➤ Commerce ➤ B 9th Jones B ➤ Calhoun 5th B 5th 14 B B ➤ MC Throckmorton➤ To Cultural District & West 7th 7th 10 B 19 12 10th B 6 Throckmorton 28 14th Henderson Florence St. ➤ Cherr Jennings Macon Texas Burnett Lamar Taylor Monroe 32 15th Commerce y Houston St. ➤ 5 29 13th JANUARY 2016 ★ To I-30 From I-30, sitors Bureau To Cultural District Lancaster Vi B Lancaster exit Lancaster 30 27 (westbound) to Commerce ention & to Downtown nv Co From I-30, h exit Cherry / Lancaster rt Wo (eastbound) or rt Summit (westbound) I-30 To Fo to Downtown To Near Southside I-35W © Copyright 1 Major Ripley Allen Arnold Statue 9 Etta’s Place 17 LaGrave Field 25 Tarrant County Courthouse 398 N. Taylor St. TrinityRiverVision.org 200 W. 3rd St. 817.255.5760 301 N.E. 6th St. 817.332.2287 100 W. Weatherford St. 817.884.1111 2 The Ashton Hotel 10 Federal Building 18 Maddox-Muse Center 26 TownePlace Suites by Marriott Fort Worth Downtown 610 Main St. -

Growing up Black in East Texas: Some Twentieth-Century Experiences

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 32 Issue 1 Article 8 3-1994 Growing up Black in East Texas: Some Twentieth-Century Experiences William H. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Wilson, William H. (1994) "Growing up Black in East Texas: Some Twentieth-Century Experiences," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 32 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol32/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATIO:'J 49 GROWING UP BLACK IN EAST TEXAS: SOME TWENTIETH-CENTURY EXPERIENCES f by William H. Wilson The experiences of growing up black in East Texas could be as varied as those of Charles E. Smith and Cleophus Gee. Smith's family moved from Waskom, Harrison County, to Dallas when he was a small child to escape possible violence at the hands of whites who had beaten his grandfather. Gee r matured in comfortable circumstances on the S.H. Bradley place near Tyler. ~ a large farm owned by prosperous relatives. Yet the two men lived the larg er experience of blacks in the second or third generation removed from slav ery, those born, mostly. in the 1920s or early 1930s. Gee, too, left his rural setting for Dallas, although his migration occurred later and was voluntary. -

Tyler-Longview: at the Heart of Texas: Cities' Industry Clusters Drive Growth

Amarillo Plano Population Irving Lubbock Dallas (2017): 445,208 (metros combined) Fort Worth El Paso Longview Population growth Midland Arlington Tyler (2010–17): 4.7 percent (Texas: 12.1 percent) Round Rock Odessa The Woodlands New Braunfels Beaumont Median household Port Arthur income (2017): Tyler, $54,339; Longview, $48,259 Austin (Texas: $59,206) Houston San Antonio National MSA rank (2017): Tyler, No. 199*; Longview, No. 204* Sugar Land Edinburg Mission McAllen At a Glance • The discovery of oil in East Texas helped move the region from a reliance on agriculture to a manufacturing hub with an energy underpinning. Tyler • Health care leads the list of largest employers in Tyler and Longview, the county seats of adjacent Gilmer Smith and Gregg counties. Canton Marshall • Proximity to Interstate 20 has supported logistics and retailing in the area. Brookshire Grocery Co. Athens is based in Tyler, which is also home to a Target Longview distribution center. Dollar General is building a regional distribution facility in Longview. Henderson Rusk Nacogdoches *The Tyler and Longview metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) encompass Smith, Gregg, Rusk and Upshur counties. Tyler–Longview: Health Care Growth Builds on Manufacturing, Energy Legacy HISTORY: East Texas Oilfield Changes and by the mid-1960s, Tyler’s 125 manufacturing plants Agricultural Economies employed 8,000 workers. Th e East Texas communities of Tyler and Longview, Longview, a cotton and timber town before the though 40 miles apart, are viewed as sharing an economic oil boom, attracted newcomers from throughout the base and history. Tyler’s early economy relied on agricul- South for its industrial plants. -

San Jacinto Battleground and State Historical Park: a Historical Synthesis and Archaeological Management Plan

Volume 2002 Article 3 2002 San Jacinto Battleground and State Historical Park: A Historical Synthesis and Archaeological Management Plan I. Waynne Cox Steve A. Tomka Raba Kistner, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Cox, I. Waynne and Tomka, Steve A. (2002) "San Jacinto Battleground and State Historical Park: A Historical Synthesis and Archaeological Management Plan," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2002, Article 3. https://doi.org/10.21112/ita.2002.1.3 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2002/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. San Jacinto Battleground and State Historical Park: A Historical Synthesis and Archaeological Management Plan Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2002/iss1/3 San Jacinto Battleground State Historical Park A Historical Synthesis and Archaeological Management Plan by I. -

The Proposed Fastrill Reservoir in East Texas: a Study Using

THE PROPOSED FASTRILL RESERVOIR IN EAST TEXAS: A STUDY USING GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS Michael Ray Wilson, B.S. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2009 APPROVED: Paul Hudak, Major Professor and Chair of the Department of Geography Samuel F. Atkinson, Minor Professor Pinliang Dong, Committee Member Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Wilson, Michael Ray. The Proposed Fastrill Reservoir in East Texas: A Study Using Geographic Information Systems. Master of Science (Applied Geography), December 2009, 116 pp., 26 tables, 14 illustrations, references, 34 titles. Geographic information systems and remote sensing software were used to analyze data to determine the area and volume of the proposed Fastrill Reservoir, and to examine seven alternatives. The controversial reservoir site is in the same location as a nascent wildlife refuge. Six general land cover types impacted by the reservoir were also quantified using Landsat imagery. The study found that water consumption in Dallas is high, but if consumption rates are reduced to that of similar Texas cities, the reservoir is likely unnecessary. The reservoir and its alternatives were modeled in a GIS by selecting sites and intersecting horizontal water surfaces with terrain data to create a series of reservoir footprints and volumetric measurements. These were then compared with a classified satellite imagery to quantify land cover types. The reservoir impacted the most ecologically sensitive land cover type the most. Only one alternative site appeared slightly less environmentally damaging. Copyright 2009 by Michael Ray Wilson ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge my thesis committee members, Dr. -

By Staying Focused on the Reining Horse Horizon, the Team at out West

BY BETSY LYNCH h c n y L y s Bobbie Cook’s enthusiasm for reining horses t e B led her to invest in a full-scale breeding and y b training operation in Scottsdale, Arizona. o t o Bucking the Texas-Oklahoma migration, she h saw the need for top facilities ‘Out West.’ P When you’re at Out West, you feel like you’re out West. The adobe stallion barn and office are in keeping with the desert setting y staying focused on the reining horse horizon, the the ranch, they were of like mind. Scottsdale is a growing hub team at Out West Stallion Station has turned a piece of of Reining, cutting and cow horse activity with a strong popu- B sunny Arizona real estate into a thriving training and lation of horses. When they factored in California and the breeding oasis — a true “full service” facility. growing international market, they agreed that there was, While it may seem as though the whole reining horse world indeed, a need for a first-class breeding and training operation has packed up and moved to Texas and Oklahoma, Out West in the Grand Canyon state. Stallion Station near Scottsdale, Arizona, is leading a migration Like many enthusiasts, Cook first got into horses as a hobby, of its own. Breeders and owners in the western U.S. now have even taking classes at Scottsdale Community College so she a viable option for letting their mares and stallions roost a lit- could do things right. Her first horse was an Arabian gelding tle closer to home. -

Sabine River Basin Summary Report 2018

Sabine River Basin Summary Report 2018 Prepared in Cooperation with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality The preparation of this report was financed in part through funding from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Sabine River Authority of Texas P.O. Box 579 Orange, TX 77631 Phone (409) 746-2192 Fax (409) 746-3780 Sabine Basin 2018 Summary Report Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 3 The TCRP and SRA-TX Objectives ................................................................................................... 4 Public Involvement ................................................................................................................................ 6 Water Quality Review ........................................................................................................................... 7 Water Quality Terminology ................................................................................................................ 8 Data Review Methodology ............................................................................................................... 10 Watershed Summaries .................................................................................................................... 12 Segment 0501 - Sabine River Tidal ............................................................................................. 12 Segment 0502 - Sabine River Above Tidal -

Sabine Lake Galveston Bay East Matagorda Bay Matagorda Bay Corpus Christi Bay Aransas Bay San Antonio Bay Laguna Madre Planning

River Basins Brazos River Basin Brazos-Colorado Coastal Basin TPWD Canadian River Basin Dallam Sherman Hansford Ochiltree Wolf Creek Colorado River Basin Lipscomb Gene Howe WMA-W.A. (Pat) Murphy Colorado-Lavaca Coastal Basin R i t Strategic Planning a B r ve Gene Howe WMA l i Hartley a Hutchinson R n n Cypress Creek Basin Moore ia Roberts Hemphill c ad a an C C r e Guadalupe River Basin e k Lavaca River Basin Oldham r Potter Gray ive Regions Carson ed R the R ork of Wheeler Lavaca-Guadalupe Coastal Basin North F ! Amarillo Neches River Basin Salt Fork of the Red River Deaf Smith Armstrong 10Randall Donley Collingsworth Palo Duro Canyon Neches-Trinity Coastal Basin Playa Lakes WMA-Taylor Unit Pr airie D og To Nueces River Basin wn Fo rk of t he Red River Parmer Playa Lakes WMA-Dimmit Unit Swisher Nueces-Rio Grande Coastal Basin Castro Briscoe Hall Childress Caprock Canyons Caprock Canyons Trailway N orth P Red River Basin ease River Hardeman Lamb Rio Grande River Basin Matador WMA Pease River Bailey Copper Breaks Hale Floyd Motley Cottle Wilbarger W To Wichita hi ng ver Sabine River Basin te ue R Foard hita Ri er R ive Wic Riv i r Wic Clay ta ve er hita hi Pat Mayse WMA r a Riv Rive ic Eisenhower ichit r e W h W tl Caddo National Grassland-Bois D'arc 6a Nort Lit San Antonio River Basin Lake Arrowhead Lamar Red River Montague South Wichita River Cooke Grayson Cochran Fannin Hockley Lubbock Lubbock Dickens King Baylor Archer T ! Knox rin Bonham North Sulphur San Antonio-Nueces Coastal Basin Crosby r it River ive y R Bowie R B W iv os r es -

Distribution of Unionid Mussels in the Big Thicket

DISTRIBUTION OF UNIONID MUSSELS IN THE BIG THICKET REGION OF TEXAS by Alison A. Tarter, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science with a Major in Aquatic Resources May 2019 Committee Members: Astrid N. Schwalb, Chair Thomas B. Hardy Clinton Robertson COPYRIGHT by Alison A. Tarter 2019 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Alison A. Tarter, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my committee chair, Dr. Astrid Schwalb, for introducing me to the intricate world of the unionids. Thank you to committee member Dr. Thom Hardy for having faith in me even when I didn’t. Thank you both for being outstanding mentors and for your patient guidance and untiring support for my research and funding. Thank you both for being there through the natural and atypical disasters that seemed to follow this thesis project. Thank you to committee member Clint Robertson for the invaluable instruction with species identification and day of help in the field. Thank you to David Rodriguez and Stephen Harding for the DNA analyses. -

James Gaines Home HABS No. TEX-367 Pendleton's Ferry, Saline County, Texas ~Re*

James Gaines Home HABS No. TEX-367 Pendleton's Ferry, Saline County, Texas ~re* PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA' HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY # Birdsall P, Briscoe, District Officer 4301 Main Street, Houston, Texas. Tez-S67 U h& ?age 1 X GAINES (NOW MCGOYWN HOUSE) . 3, ' Pendleton Ferry, {Old Gaines Ferry) Sabine County, Texas 2 Owner James Polly McGowaxu ' Date of Erection 1320. Architect K o ne♦ Builder Unknown, probably the original owner* Present Qondition Good Number of Stories one story Other Existing flecqrds Unknown Materials of Construction Log Additional Data %is WRS an important piece in early history on account of location at ferry on King's Highway at Sabine River crossing. All early settlers in riorth ^ast Tex^o passed through here. Gamino Heal led from here through Nacogdoches to San Antonio and from there to Monclova, Cohuilla and thence to Mexico City. This place is so excellent in scale that it might serve as a model to pattern all houses of this type. In the photograph the fence hugged the face of the porch so tightly that it was impossible to have the'-house without the fence. The posts are trimmed logs and nicely spaced. Generally, the house consists of a breeze-way through the center with a large room on each side and at the rear .there is architecture's first off-spring, a lean too, whether the shingle roof dates from 1820 is open to question but the owner is to be congratulated that the shingles have been replaced and that he did not succumb to some ubiquitious seller of corrugated iron. -

Stormwater Management Program 2013-2018 Appendix A

Appendix A 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) As required under Sections 303(d) and 304(a) of the federal Clean Water Act, this list identifies the water bodies in or bordering Texas for which effluent limitations are not stringent enough to implement water quality standards, and for which the associated pollutants are suitable for measurement by maximum daily load. In addition, the TCEQ also develops a schedule identifying Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) that will be initiated in the next two years for priority impaired waters. Issuance of permits to discharge into 303(d)-listed water bodies is described in the TCEQ regulatory guidance document Procedures to Implement the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (January 2003, RG-194). Impairments are limited to the geographic area described by the Assessment Unit and identified with a six or seven-digit AU_ID. A TMDL for each impaired parameter will be developed to allocate pollutant loads from contributing sources that affect the parameter of concern in each Assessment Unit. The TMDL will be identified and counted using a six or seven-digit AU_ID. Water Quality permits that are issued before a TMDL is approved will not increase pollutant loading that would contribute to the impairment identified for the Assessment Unit. Explanation of Column Headings SegID and Name: The unique identifier (SegID), segment name, and location of the water body. The SegID may be one of two types of numbers. The first type is a classified segment number (4 digits, e.g., 0218), as defined in Appendix A of the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (TSWQS).