Wide Impact Assessment (SWIA) of Myanmar's Oil & Gas Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CENTRALIZED NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT for MYANMAR 2018 – 1 of 178 –

Centralized National Risk Assessment for Myanmar FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 EN FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 CENTRALIZED NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT FOR MYANMAR 2018 – 1 of 178 – Title: Centralized National Risk Assessment for Myanmar Document reference FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 EN code: Approval body: FSC International Center: Performance and Standards Unit Date of approval: 27 August 2018 Contact for comments: FSC International Center - Performance and Standards Unit - Adenauerallee 134 53113 Bonn, Germany +49-(0)228-36766-0 +49-(0)228-36766-30 [email protected] © 2018 Forest Stewardship Council, A.C. All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the publisher’s copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, recording taping, or information retrieval systems) without the written permission of the publisher. Printed copies of this document are for reference only. Please refer to the electronic copy on the FSC website (ic.fsc.org) to ensure you are referring to the latest version. The Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC) is an independent, not for profit, non- government organization established to support environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial, and economically viable management of the world’s forests. FSC’s vision is that the world’s forests meet the social, ecological, and economic rights and needs of the present generation without compromising those of future generations. FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 CENTRALIZED NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT FOR MYANMAR 2018 – 2 of 178 – Contents Risk assessments that have been finalized for Myanmar .......................................... 4 Risk designations in finalized risk assessments for Myanmar ................................... -

Xa0054978 Prevalence of Antibody to Foot-And-Mouth Disease in Cattle and Buffalo in Myanmar

XA0054978 PREVALENCE OF ANTIBODY TO FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE IN CATTLE AND BUFFALO IN MYANMAR M. MAUNG KYIN Foot-and-mouth Disease Laboratory, Livestock Breeding & Veterinary Department, Ministry of Livestock & Fisheries, Insein, Yangon, Myanmar Abstract PREVALENCE OF ANTIBODY TO FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE IN CATTLE AND BUFFALO IN MYANMAR A serological survey for the prevalence of antibody to foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) was performed in six Divisions and three States in Myanmar. A liquid phase blocking ELISA prepared and standardized by World Reference Laboratory (WRL) for FMD was used for this study. A total of 831 serum samples from cattle and buffalo were collected by a random process and assayed for antibody against FMD virus types O, A, C and Asia I. Positive reactions to FMD virus O, A, C, and Asia I sero-types were detected. Even in the free zone area, (Ngape township) and the buffer zone (Minbu township) serum samples showed positive reactions. Ten percent of the sera tested showed positive reactions to all sero-types within the free zone and buffer zone. The majority of cattle and buffaloes, except those in the FMD free and buffer zones, were not vaccinated against FMD. The percentage of positive sera in each State and Divisions varied from 16 to 90 for at least one sero-type. More epithelial specimens from FMD outbreaks should be submitted for investigation and further nation-wide serological surveys for FMD should be carried out if a national policy for FMD control and eradication is to be effective and enforceable. 1. INTRODUCTION Myanmar is primarily an agricultural country and is undertaking measures not only to produce more food for domestic consumption but also for export. -

Sector-Wide Impact Assessment Oil And

Sector Wide Impact Assessment Myanmar Oil & Gas Sector Wide Impact Assessment The Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business (MCRB) was set up in 2013 by the Institute for Human Rights and Business (IHRB) and the Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR) with funding from several donor governments. Based in Yangon, it aims to provide a trusted and impartial platform for the creation of knowledge, capacity, and dialogue amongst businesses, civil society organisations and governments to encourage responsible business conduct throughout Myanmar. Responsible business means business conduct that works for the long- term interests of Myanmar and its people, based on responsible social and environmental performance within the context of international standards. © Copyright Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business (MCRB), Institute for Human Rights and Business (IHRB), and Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR), September 2014. Published by MCRB, IHRB and DIHR. Citation: MCRB, IHRB and DIHR, "Myanmar Oil & Gas Sector-Wide Impact Assessment (SWIA)" (Sept. 2014) All rights reserved. MCRB, IHRB and DIHR permit free reproduction of extracts from this publication provided that due acknowledgment is given and a copy of the publication carrying the extract is sent to the headquarter addresses below. Requests for permission to reproduce and translate the publication should be addressed to MCRB, IHRB and DIHR. ISBN: 978-1-908405-20-3 Myanmar Centre for Institute for Human Rights Danish Institute for Responsible Business and Business (IHRB) Human Rights (DIHR) 15 Shan Yeiktha Street 34b York Way Wilders Plads 8K Sanchaung, Yangon, London, N1 9AB 1403 Copenhagen K Myanmar United Kingdom Email: Email: info@myanmar- Email: [email protected] [email protected] responsiblebusiness.org Web: www.ihrb.org Web: Web: www.myanmar- www.humanrights.dk responsiblebusiness.org or www.mcrb.org.mm Acknowledgements The partner organisations would like to thank the Governments of Denmark, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland and United Kingdom for their on-going support to MCRB. -

MHAA 2019 Annual Report.Pdf

Establishment of MHAA in Myanmar Project Implementing Township of MHAA FOREWARD Health Assistants career has been established since 1953 and it has been more than sixty years of profession. Despite the long period of establishment, it is still in need to augment the opportunities for long-term development of Health Assistants. There are three types of Health Assistants: Regular Health Assistant (RHA), Condensed Health Assistant (CHA) and BCommH (HA) based on the need of different health programs and projects carried out by successive governments. Although there are gaps in terms of generation and educational background, we have come together to shape a shared vision of becoming a resourceful public health taskforce, to expand access to career development and advanced educational opportunities leading to the health-related benefits of community. It is crucial to have a collective voice of all Health Assistants in order to achieve our common vision and missions and likewise the role of MHAA is foundational. At the moment, MHAA in township level has been specifically formed in 312 townships and co-owned by the members who are counting at 6,331 and more from across the country. We have mutual partnership with 6 international donor agencies, 11 partners and 15 implementing public health related projects in 89 townships of 11 regions and states. Currently, we have the full-time staff capacity at 605. The MHAA yearly expenditure volume increased over two-folds to 7.1 million US dollars in FY 2019 from over 3 million US dollars in FY 2018. Moreover, MHAA developed a five years strategic plan which will guide MHAA to perform integrated response to health under all projects as well as achieve more population coverage and better health outcomes fulfilling building blocks for Universal Health Coverage (UHC) in project areas. -

Total Detention, Charge Lists English (Last Updated on 29 March 2021)

Date of Current No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Section of Law Plaintiff Address Remark Arrest Condition S: 8 of the Export Superinte and Import Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and ndent and S: 25 of the Senior NLD leaders including Daw Kyi Lin Natural Disaster Aung San Suu Kyi and President U of Special General Aung State Counsellor (Chairman of Management law, Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F 1-Feb-21 Branch, House Arrest Naypyitaw San NLD) Penal Code - chief ministers and ministers in the Dekkhina 505(B), S: 67 of states and regions were also detained. District the Administr Telecommunicatio ator ns Law S: 25 of the Superinte Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Natural Disaster ndent Senior NLD leaders including Daw Management law, Myint Aung San Suu Kyi and President U President (Vice Chairman-1 of Penal Code - Naing, Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw NLD) 505(B), S: 67 of Dekkhina chief ministers and ministers in the the District states and regions were also detained. Telecommunicatio Administr ns Law ator Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Speaker of the Union Assembly, Aung San Suu Kyi and President U the Joint House and Pyithu Win Myint were detained. -

Myanmar Oil & Gas Sector Wide Impact Assessment

Sector Wide Impact Assessment Myanmar Oil & Gas Sector Wide Impact Assessment The Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business (MCRB) was set up in 2013 by the Institute for Human Rights and Business (IHRB) and the Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR) with funding from several donor governments. Based in Yangon, it aims to provide a trusted and impartial platform for the creation of knowledge, capacity, and dialogue amongst businesses, civil society organisations and governments to encourage responsible business conduct throughout Myanmar. Responsible business means business conduct that works for the long- term interests of Myanmar and its people, based on responsible social and environmental performance within the context of international standards. © Copyright Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business (MCRB), Institute for Human Rights and Business (IHRB), and Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR), September 2014. Published by MCRB, IHRB and DIHR. Citation: MCRB, IHRB and DIHR, "Myanmar Oil & Gas Sector-Wide Impact Assessment (SWIA)" (Sept. 2014) All rights reserved. MCRB, IHRB and DIHR permit free reproduction of extracts from this publication provided that due acknowledgment is given and a copy of the publication carrying the extract is sent to the headquarter addresses below. Requests for permission to reproduce and translate the publication should be addressed to MCRB, IHRB and DIHR. ISBN: 978-1-908405-20-3 Myanmar Centre for Institute for Human Rights Danish Institute for Responsible Business and Business (IHRB) Human Rights (DIHR) 15 Shan Yeiktha Street 34b York Way Wilders Plads 8K Sanchaung, Yangon, London, N1 9AB 1403 Copenhagen K Myanmar United Kingdom Email: Email: info@myanmar- Email: [email protected] [email protected] responsiblebusiness.org Web: www.ihrb.org Web: Web: www.myanmar- www.humanrights.dk responsiblebusiness.org or www.mcrb.org.mm Acknowledgements The partner organisations would like to thank the Governments of Denmark, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland and United Kingdom for their on-going support to MCRB. -

Project Administration Manual

Accelerated Rural Electrification Project (RRP MYA 53223) Project Administration Manual Project Number: 53223-001 Loan Number: XXXX November 2020 Republic of the Union of Myanmar: Accelerated Rural Electrification Development Project ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank APFS – audited project financial statements CBA – community based assessment ECD – Environmental Conservation Department EMP – environmental management plan EIA – environmental impact assessment ESE – Electricity Supply Enterprise FMA – financial management assessment IEE – initial environmental examination MOEE – Ministry of Electricity and Energy OAG – Office of the Auditor General OCB – open competitive bidding PAM – project administration manual PIC – project implementation consultant PIU – project implementation unit PMU – project management unit REGDP – resettlement and ethnic group development plan SEMP – site environmental management plan SCS – Stakeholder Communication Strategy SPS – ADB’s Safeguard Policy Statement 2009 Weights and Measures km – kilometer kV – kilovolt MVA – megavolt-ampere CONTENTS I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1 II. IMPLEMENTATION PLANS 2 A. Project Readiness Activities 2 B. Overall Project Implementation Plan 3 III. PROJECT MANAGEMENT ARRANGEMENTS 4 A. Project Implementation Organizations: Roles and Responsibilities 4 B. Key Persons Involved in Implementation 5 C. Project Organization Structure 6 IV. COSTS AND FINANCING 7 A. Cost Estimates Preparation and Revisions 7 B. Key Assumptions 8 C. Detailed Cost Estimates by Expenditure Category 9 D. Allocation and Withdrawal of Loan Proceeds 10 E. Detailed Cost Estimates by Financier 11 F. Detailed Cost Estimates by Outputs and/or Components 12 G. Detailed Cost Estimates by Year 13 H. Contract and Disbursement S-Curve 14 I. Fund Flow Diagram 15 V. FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT 16 A. Financial Management Assessment 16 B. Disbursement 17 C. Accounting 18 D. -

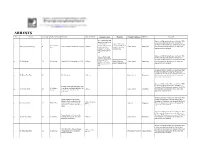

Recent Arrests List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 8 of the Export and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Import Law and S: 25 Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and of the Natural Disaster Lin of Special Branch regions were also detained. Management law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 25 of the Natural President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and Naing law regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and parliament regions were also detained. -

The Conservation Status of Hoolock Gibbons in Myanmar

The Conservation Status of Hoolock Gibbons in Myanmar Thomas Geissmann Mark E. Grindley Ngwe Lwin Saw Soe Aung Thet Naing Aung Saw Blaw Htoo Frank Momberg People Resources and Conservation Foundation Fauna & Flora International Myanmar Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association Gibbon Conservation Alliance Karen Environmental and Social Action Network The Conservation Status of Hoolock Gibbons in Myanmar by Thomas Geissmann, Mark E. Grindley, Ngwe Lwin, Saw Soe Aung, Thet Naing Aung, Saw Blaw Htoo, and Frank Momberg 2013 ii The Conservation Status of Hoolock Gibbons in Myanmar Authors: Thomas Geissmann, Gibbon Conservation Alliance, and Anthropological Institute, University Zürich-Irchel, Winterthurerstr. 190, CH–8057 Zürich, Switzerland Mark E Grindley, Chief Technical Officer, Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand Programs, People Resources and Conservation Foundation, Chiang Mai, Thailand Ngwe Lwin, Field Project Coordinator, Myanmar Primate Conservation Program, Yangon, Myanmar Saw Soe Aung, Senior Biologist, Myanmar Primate Conservation Program, Yangon, Myanmar Thet Naing Aung, Junior Biologist, Myanmar Primate Conservation Program, Yangon, Myanmar Saw Blaw Htoo, Community Conservation Manager, Karen Environmental and Social Action Network, Chiang Mai, Thailand Frank Momberg, Asia Director for Program Development, Fauna and Flora International, Jakarta, Indonesia Published by: Gibbon Conservation Alliance Anthropological Institute University Zürich-Irchel Winterthurerstrasse 190 CH–8057 Zürich, Switzerland Email: [email protected] Web: www.gibbonconservation.org Copyright: © 2013 Fauna & Flora International, People Resources and Conservation Foundation, Myanmar Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association, and Gibbon Conservation Alliance. The copyright of the photographs used in this publication lies with the individual photographers. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial uses is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder(s) provided the source is fully acknowledged. -

Recent Arrest List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s General Aung Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and San law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent Myint President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Naing, Dekkhina House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the District Administrator regions were also detained. Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

Annex A: Annex Additional Information on SWIA Methodology

A Annex A: Annex Additional Information on SWIA Methodology A. SWIA Phases The SWIA process follows well-established impact assessment steps. For each step of the process specific tools or approaches have been developed, which are described below.481 III. Idenification & IV. Mitigation and V. Consultation & I. Screening! II. Scoping! Assessment of Impact Impacts! Management! Finalisation! Box 26: SWIA Phases I. Screening Objective: Select economic sectors for a SWIA based on several Key Outputs / criteria: Tools n the importance of the sector to the Myanmar economy n Selection of 4 n the complexity and scale of human rights risks involved in the sectors for sector SWIA: Oil & n the diversity of potential impacts looking across the sectors Gas, Tourism, n human development potential ICT and n geographical area Agriculture Tasks: n Informal consultations were held inside and outside Myanmar to develop and verify the selection of sectors. II. Scoping the O&G sector in Myanmar Objective: Develop foundational knowledge base to target field Key Outputs / research for validation and deepening of data collection. Tools n Scoping papers Tasks: n SWIA work plan n Commission expert background papers on: the O&G sector; the legal framework; land and labour issues n Stakeholder mapping III. Identification and Assessment of Impacts Objective: Validate foundational knowledge base with primary Key Outputs / 481 This table has been gratefully adapted from the presentation used in Kuoni’s HRIA of the tourism sector in Kenya. 216 ANNEX A: ADDITIONAL INFORMATION -

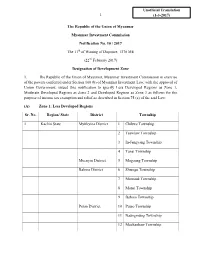

Zone Notification

Unofficial Translation 1 (1-3-2017) The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Myanmar Investment Commission Notification No. 10 / 2017 The 11th of Waning of Dapotwe, 1378 ME (22nd February 2017) Designation of Development Zone 1. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Myanmar Investment Commission in exercise of the powers conferred under Section 100 (b) of Myanmar Investment Law, with the approval of Union Government, issued this notification to specify Less Developed Regions as Zone 1, Moderate Developed Regions as Zone 2 and Developed Regions as Zone 3 as follows for the purpose of income tax exemption and relief as described in Section 75 (a) of the said Law: (A) Zone 1: Less Developed Regions Sr. No. Region/ State District Township 1 Kachin State Myitkyina District 1 Chibwe Township 2 Tsawlaw Township 3 In-Jangyang Township 4 Tanai Township Moenyin District 5 Mogaung Township Bahmo District 6 Shwegu Township 7 Momauk Township 8 Mansi Township 9 Bahmo Township Putao District 10 Putao Township 11 Naungmung Township 12 Machanbaw Township 2 13 Sumprabum Township 14 Kaunglanhpu Township 2 Kayah State Bawlakhe District 1 BawlakheTownship 2 Hpasaung Township 3 Mese Township Loikaw District 4 Loikaw Township 5 Demawso Township 6 Hpruso Township 7 Shataw Township 3 Kayin State Hpa-an District 1 Hpa-an Township 2 Hlaignbwe Township 3 Papun Township 4 Thandaunggyi Township Kawkareik District 5 Kawkareik Township 6 Kyain Seikkyi Township Myawady District 7 Myawady Township 4 Chin State Falam District 1 Falam Township 2 Tiddim Township 3 Hton Zan Township