Pluto and the Kuiper Belt the Solar System Beyond Neptune

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy

Barucci et al.: Surface Characteristics of TNOs and Centaurs 647 Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy M. A. Barucci and A. Doressoundiram Observatoire de Paris D. P. Cruikshank NASA Ames Research Center The external region of the solar system contains a vast population of small icy bodies, be- lieved to be remnants from the accretion of the planets. The transneptunian objects (TNOs) and Centaurs (located between Jupiter and Neptune) are probably made of the most primitive and thermally unprocessed materials of the known solar system. Although the study of these objects has rapidly evolved in the past few years, especially from dynamical and theoretical points of view, studies of the physical and chemical properties of the TNO population are still limited by the faintness of these objects. The basic properties of these objects, including infor- mation on their dimensions and rotation periods, are presented, with emphasis on their diver- sity and the possible characteristics of their surfaces. 1. INTRODUCTION cally with even the largest telescopes. The physical char- acteristics of Centaurs and TNOs are still in a rather early Transneptunian objects (TNOs), also known as Kuiper stage of investigation. Advances in instrumentation on tele- belt objects (KBOs) and Edgeworth-Kuiper belt objects scopes of 6- to 10-m aperture have enabled spectroscopic (EKBOs), are presumed to be remnants of the solar nebula studies of an increasing number of these objects, and signifi- that have survived over the age of the solar system. The cant progress is slowly being made. connection of the short-period comets (P < 200 yr) of low We describe here photometric and spectroscopic studies orbital inclination and the transneptunian population of pri- of TNOs and the emerging results. -

The Dynamics of Plutinos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server The dynamics of Plutinos Qingjuan Yu and Scott Tremaine Princeton University Observatory, Peyton Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1001, USA ABSTRACT Plutinos are Kuiper-belt objects that share the 3:2 Neptune resonance with Pluto. The long-term stability of Plutino orbits depends on their eccentric- ity. Plutinos with eccentricities close to Pluto (fractional eccentricity difference < ∆e=ep = e ep =ep 0:1) can be stable because the longitude difference librates, | − | ∼ in a manner similar to the tadpole and horseshoe libration in coorbital satellites. > Plutinos with ∆e=ep 0:3 can also be stable; the longitude difference circulates ∼ and close encounters are possible, but the effects of Pluto are weak because the encounter velocity is high. Orbits with intermediate eccentricity differences are likely to be unstable over the age of the solar system, in the sense that encoun- ters with Pluto drive them out of the 3:2 Neptune resonance and thus into close encounters with Neptune. This mechanism may be a source of Jupiter-family comets. Subject headings: planets and satellites: Pluto — Kuiper Belt, Oort cloud — celestial mechanics, stellar dynamics 1. Introduction The orbit of Pluto has a number of unusual features. It has the highest eccentricity (ep =0:253) and inclination (ip =17:1◦) of any planet in the solar system. It crosses Neptune’s orbit and hence is susceptible to strong perturbations during close encounters with that planet. However, close encounters do not occur because Pluto is locked into a 3:2 orbital resonance with Neptune, which ensures that conjunctions occur near Pluto’s aphelion (Cohen & Hubbard 1965). -

Astro2020 Science White Paper Modeling Debris Disk Evolution

Astro2020 Science White Paper Modeling Debris Disk Evolution Thematic Areas Planetary Systems Formation and Evolution of Compact Objects Star and Planet Formation Cosmology and Fundamental Physics Galaxy Evolution Resolved Stellar Populations and their Environments Stars and Stellar Evolution Multi-Messenger Astronomy and Astrophysics Principal Author András Gáspár Steward Observatory, The University of Arizona [email protected] 1-(520)-621-1797 Co-Authors Dániel Apai, Jean-Charles Augereau, Nicholas P. Ballering, Charles A. Beichman, Anthony Boc- caletti, Mark Booth, Brendan P. Bowler, Geoffrey Bryden, Christine H. Chen, Thayne Currie, William C. Danchi, John Debes, Denis Defrère, Steve Ertel, Alan P. Jackson, Paul G. Kalas, Grant M. Kennedy, Matthew A. Kenworthy, Jinyoung Serena Kim, Florian Kirchschlager, Quentin Kral, Sebastiaan Krijt, Alexander V. Krivov, Marc J. Kuchner, Jarron M. Leisenring, Torsten Löhne, Wladimir Lyra, Meredith A. MacGregor, Luca Matrà, Dimitri Mawet, Bertrand Mennes- son, Tiffany Meshkat, Amaya Moro-Martín, Erika R. Nesvold, George H. Rieke, Aki Roberge, Glenn Schneider, Andrew Shannon, Christopher C. Stark, Kate Y. L. Su, Philippe Thébault, David J. Wilner, Mark C. Wyatt, Marie Ygouf, Andrew N. Youdin Co-Signers Virginie Faramaz, Kevin Flaherty, Hannah Jang-Condell, Jérémy Lebreton, Sebastián Marino, Jonathan P. Marshall, Rafael Millan-Gabet, Peter Plavchan, Luisa M. Rebull, Jacob White Abstract Understanding the formation, evolution, diversity, and architectures of planetary systems requires detailed knowledge of all of their components. The past decade has shown a remarkable increase in the number of known exoplanets and debris disks, i.e., populations of circumstellar planetes- imals and dust roughly analogous to our solar system’s Kuiper belt, asteroid belt, and zodiacal dust. -

New Horizons Pluto/KBO Mission Impact Hazard

New Horizons Pluto/KBO Mission Impact Hazard Hal Weaver NH Project Scientist The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Outline • Background on New Horizons mission • Description of Impact Hazard problem • Impact Hazard mitigation – Hubble Space Telescope plays a key role New Horizons: To Pluto and Beyond The Initial Reconnaissance of The Solar System’s “Third Zone” KBOs Pluto-Charon Jupiter System 2016-2020 July 2015 Feb-March 2007 Launch Jan 2006 PI: Alan Stern (SwRI) PM: JHU Applied Physics Lab New Horizons is NASA’s first New Frontiers Mission Frontier of Planetary Science Explore a whole new region of the Solar System we didn’t even know existed until the 1990s Pluto is no longer an outlier! Pluto System is prototype of KBOs New Horizons gives the first close-up view of these newly discovered worlds New Horizons Now (overhead view) NH Spacecraft & Instruments 2.1 meters Science Team: PI: Alan Stern Fran Bagenal Rick Binzel Bonnie Buratti Andy Cheng Dale Cruikshank Randy Gladstone Will Grundy Dave Hinson Mihaly Horanyi Don Jennings Ivan Linscott Jeff Moore Dave McComas Bill McKinnon Ralph McNutt Scott Murchie Cathy Olkin Carolyn Porco Harold Reitsema Dennis Reuter Dave Slater John Spencer Darrell Strobel Mike Summers Len Tyler Hal Weaver Leslie Young Pluto System Science Goals Specified by NASA or Added by New Horizons New Horizons Resolution on Pluto (Simulations of MVIC context imaging vs LORRI high-resolution "noodles”) 0.1 km/pix The Best We Can Do Now 0.6 km/pix HST/ACS-PC: 540 km/pix New Horizons Science Status • -

A Deep Search for Additional Satellites Around the Dwarf Planet

Search for Additional Satellites around Haumea A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 01/23/15 A DEEP SEARCH FOR ADDITIONAL SATELLITES AROUND THE DWARF PLANET HAUMEA Luke D. Burkhart1,2, Darin Ragozzine1,3,4, Michael E. Brown5 Search for Additional Satellites around Haumea ABSTRACT Haumea is a dwarf planet with two known satellites, an unusually high spin rate, and a large collisional family, making it one of the most interesting objects in the outer solar system. A fully self-consistent formation scenario responsible for the satellite and family formation is still elusive, but some processes predict the initial formation of many small moons, similar to the small moons recently discovered around Pluto. Deep searches for regular satellites around KBOs are difficult due to observational limitations, but Haumea is one of the few for which sufficient data exist. We analyze Hubble Space Telescope (HST) observations, focusing on a ten-consecutive-orbit sequence obtained in July 2010, to search for new very small satellites. To maximize the search depth, we implement and validate a non-linear shift-and-stack method. No additional satellites of Haumea are found, but by implanting and recovering artificial sources, we characterize our sensitivity. At distances between 10,000 km and 350,000 km from Haumea, satellites with radii as small as 10 km are ruled out, assuming∼ an albedo∼ (p 0.7) similar to Haumea. We also rule out satellites larger∼ than &40 km in most of the Hill sphere using≃ other HST data. This search method rules out objects similar in size to the small moons of Pluto. -

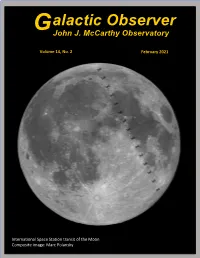

Alactic Observer

alactic Observer G John J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 14, No. 2 February 2021 International Space Station transit of the Moon Composite image: Marc Polansky February Astronomy Calendar and Space Exploration Almanac Bel'kovich (Long 90° E) Hercules (L) and Atlas (R) Posidonius Taurus-Littrow Six-Day-Old Moon mosaic Apollo 17 captured with an antique telescope built by John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer is credited with being the first to photograph the Moon in Tranquility Base England in February 1852 Apollo 11 Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites are visible in the images, as well as Mare Nectaris, one of the older impact basins on Mare Nectaris the Moon Altai Scarp Photos: Bill Cloutier 1 John J. McCarthy Observatory In This Issue Page Out the Window on Your Left ........................................................................3 Valentine Dome ..............................................................................................4 Rocket Trivia ..................................................................................................5 Mars Time (Landing of Perseverance) ...........................................................7 Destination: Jezero Crater ...............................................................................9 Revisiting an Exoplanet Discovery ...............................................................11 Moon Rock in the White House....................................................................13 Solar Beaming Project ..................................................................................14 -

CHORUS: Let's Go Meet the Dwarf Planets There Are Five in Our Solar

Meet the Dwarf Planet Lyrics: CHORUS: Let’s go meet the dwarf planets There are five in our solar system Let’s go meet the dwarf planets Now I’ll go ahead and list them I’ll name them again in case you missed one There’s Pluto, Ceres, Eris, Makemake and Haumea They haven’t broken free from all the space debris There’s Pluto, Ceres, Eris, Makemake and Haumea They’re smaller than Earth’s moon and they like to roam free I’m the famous Pluto – as many of you know My orbit’s on a different path in the shape of an oval I used to be planet number 9, But I break the rules; I’m one of a kind I take my time orbiting the sun It’s a long, long trip, but I’m having fun! Five moons keep me company On our epic journey Charon’s the biggest, and then there’s Nix Kerberos, Hydra and the last one’s Styx 248 years we travel out Beyond the other planet’s regular rout We hang out in the Kuiper Belt Where the ice debris will never melt CHORUS My name is Ceres, and I’m closest to the sun They found me in the Asteroid Belt in 1801 I’m the only known dwarf planet between Jupiter and Mars They thought I was an asteroid, but I’m too round and large! I’m Eris the biggest dwarf planet, and the slowest one… It takes me 557 years to travel around the sun I have one moon, Dysnomia, to orbit along with me We go way out past the Kuiper Belt, there’s so much more to see! CHORUS My name is Makemake, and everyone thought I was alone But my tiny moon, MK2, has been with me all along It takes 310 years for us to orbit ‘round the sun But out here in the Kuiper Belt… our adventures just begun Hello my name’s Haumea, I’m not round shaped like my friends I rotate fast, every 4 hours, which stretched out both my ends! Namaka and Hi’iaka are my moons, I have just 2 And we live way out past Neptune in the Kuiper Belt it’s true! CHORUS Now you’ve met the dwarf planets, there are 5 of them it’s true But the Solar System is a great big place, with more exploring left to do Keep watching the skies above us with a telescope you look through Because the next person to discover one… could be me or you… . -

Dwarf Planet Ceres

Dwarf Planet Ceres drishtiias.com/printpdf/dwarf-planet-ceres Why in News As per the data collected by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft, dwarf planet Ceres reportedly has salty water underground. Dawn (2007-18) was a mission to the two most massive bodies in the main asteroid belt - Vesta and Ceres. Key Points 1/3 Latest Findings: The scientists have given Ceres the status of an “ocean world” as it has a big reservoir of salty water underneath its frigid surface. This has led to an increased interest of scientists that the dwarf planet was maybe habitable or has the potential to be. Ocean Worlds is a term for ‘Water in the Solar System and Beyond’. The salty water originated in a brine reservoir spread hundreds of miles and about 40 km beneath the surface of the Ceres. Further, there is an evidence that Ceres remains geologically active with cryovolcanism - volcanoes oozing icy material. Instead of molten rock, cryovolcanoes or salty-mud volcanoes release frigid, salty water sometimes mixed with mud. Subsurface Oceans on other Celestial Bodies: Jupiter’s moon Europa, Saturn’s moon Enceladus, Neptune’s moon Triton, and the dwarf planet Pluto. This provides scientists a means to understand the history of the solar system. Ceres: It is the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It was the first member of the asteroid belt to be discovered when Giuseppe Piazzi spotted it in 1801. It is the only dwarf planet located in the inner solar system (includes planets Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars). Scientists classified it as a dwarf planet in 2006. -

Mass of the Kuiper Belt · 9Th Planet PACS 95.10.Ce · 96.12.De · 96.12.Fe · 96.20.-N · 96.30.-T

Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Mass of the Kuiper Belt E. V. Pitjeva · N. P. Pitjev Received: 13 December 2017 / Accepted: 24 August 2018 The final publication ia available at Springer via http://doi.org/10.1007/s10569-018-9853-5 Abstract The Kuiper belt includes tens of thousands of large bodies and millions of smaller objects. The main part of the belt objects is located in the annular zone between 39.4 au and 47.8 au from the Sun, the boundaries correspond to the average distances for orbital resonances 3:2 and 2:1 with the motion of Neptune. One-dimensional, two-dimensional, and discrete rings to model the total gravitational attraction of numerous belt objects are consid- ered. The discrete rotating model most correctly reflects the real interaction of bodies in the Solar system. The masses of the model rings were determined within EPM2017—the new version of ephemerides of planets and the Moon at IAA RAS—by fitting spacecraft ranging observations. The total mass of the Kuiper belt was calculated as the sum of the masses of the 31 largest trans-neptunian objects directly included in the simultaneous integration and the estimated mass of the model of the discrete ring of TNO. The total mass −2 is (1.97 ± 0.30) · 10 m⊕. The gravitational influence of the Kuiper belt on Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune exceeds at times the attraction of the hypothetical 9th planet with a mass of ∼ 10 m⊕ at the distances assumed for it. -

Should Earth Get Demoted from Planet Status Just Like Pluto?

IOSR Journal of Applied Physics (IOSR-JAP) e-ISSN: 2278-4861.Volume 10, Issue 3 Ver. I (May. – June. 2018), PP 15-19 www.iosrjournals.org Should Earth Get Demoted From Planet Status Just Like Pluto? Dipak Nath Assistant Professor, HOD, Department of Physics, Sao Chang Govt College, Tuensang;Nagaland, India. Corresponding Author: Dipak Nath Abstract: Clyde.W. Tombough discovered Pluto on march13, 1930. From its discovery in 1930 until 2006, Pluto was classified as Planet. In the late 20th and early 21st century, many objects similar to Pluto were discovered in the outer solar system, notably the scattered disc object Eris in 2005, which is 27% more massive than Pluto. On august-24, 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) defined what it means to be a Planet within the solar system. This definition excluded Pluto as a Planet added it as a member of the new category “Dwarf Planet” along with Eris and Ceres. There were many reasons why Pluto got demoted to dwarf planet status, one of which was that it couldn't clear its orbit of asteroids and other debris. But Earth's orbit is also crowded...too crowded for Earth to be a planet? Earth is indeed in a very crowded orbit, surrounded by tens of thousands of asteroids and other objects. The presence of so many asteroids seems like a serious problem for Earth's claim that it has cleared its neighborhood. And Earth isn't alone in this problem - Jupiter is surrounded by some 100,000 Trojan asteroids, and there's similar clutter around Mars and Neptune. -

What Is the Color of Pluto? - Universe Today

What is the Color of Pluto? - Universe Today space and astronomy news Universe Today Home Members Guide to Space Carnival Photos Videos Forum Contact Privacy Login NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft captured this high-resolution enhanced color view of http://www.universetoday.com/13866/color-of-pluto/[29-Mar-17 13:18:37] What is the Color of Pluto? - Universe Today Pluto on July 14, 2015. Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI WHAT IS THE COLOR OF PLUTO? Article Updated: 28 Mar , 2017 by Matt Williams When Pluto was first discovered by Clybe Tombaugh in 1930, astronomers believed that they had found the ninth and outermost planet of the Solar System. In the decades that followed, what little we were able to learn about this distant world was the product of surveys conducted using Earth-based telescopes. Throughout this period, astronomers believed that Pluto was a dirty brown color. In recent years, thanks to improved observations and the New Horizons mission, we have finally managed to obtain a clear picture of what Pluto looks like. In addition to information about its surface features, composition and tenuous atmosphere, much has been learned about Pluto’s appearance. Because of this, we now know that the one-time “ninth planet” of the Solar System is rich and varied in color. Composition: With a mean density of 1.87 g/cm3, Pluto’s composition is differentiated between an icy mantle and a rocky core. The surface is composed of more than 98% nitrogen ice, with traces of methane and carbon monoxide. Scientists also suspect that Pluto’s internal structure is differentiated, with the rocky material having settled into a dense core surrounded by a mantle of water ice. -

The Solar System Cause Impact Craters

ASTRONOMY 161 Introduction to Solar System Astronomy Class 12 Solar System Survey Monday, February 5 Key Concepts (1) The terrestrial planets are made primarily of rock and metal. (2) The Jovian planets are made primarily of hydrogen and helium. (3) Moons (a.k.a. satellites) orbit the planets; some moons are large. (4) Asteroids, meteoroids, comets, and Kuiper Belt objects orbit the Sun. (5) Collision between objects in the Solar System cause impact craters. Family portrait of the Solar System: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, (Eris, Ceres, Pluto): My Very Excellent Mother Just Served Us Nine (Extra Cheese Pizzas). The Solar System: List of Ingredients Ingredient Percent of total mass Sun 99.8% Jupiter 0.1% other planets 0.05% everything else 0.05% The Sun dominates the Solar System Jupiter dominates the planets Object Mass Object Mass 1) Sun 330,000 2) Jupiter 320 10) Ganymede 0.025 3) Saturn 95 11) Titan 0.023 4) Neptune 17 12) Callisto 0.018 5) Uranus 15 13) Io 0.015 6) Earth 1.0 14) Moon 0.012 7) Venus 0.82 15) Europa 0.008 8) Mars 0.11 16) Triton 0.004 9) Mercury 0.055 17) Pluto 0.002 A few words about the Sun. The Sun is a large sphere of gas (mostly H, He – hydrogen and helium). The Sun shines because it is hot (T = 5,800 K). The Sun remains hot because it is powered by fusion of hydrogen to helium (H-bomb). (1) The terrestrial planets are made primarily of rock and metal.