Voice Classification and Fach: Recent, Historical and Conflicting Systems of Voice Categorization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

The Singing Telegram

THE SINGING TELEGRAM Happy almost New Year! Well, New Year from the perspective of LOON’s season, at any rate! As we close out this season with the fun and shimmer of our Summer Sparkler, we reflect back on the year while we also look forward to the season to come. Thanks to all who made Don Giovanni such a success! Host families, yard sign posters, volunteer painters, stitchers, poster-hangers, ushers, and donors are a part of the success of any production, right along with the singers, designers, orchestra, and tech crew. Thanks to ALL for bringing this imaginative and engaging produc- tion to the stage! photos by: Michelle Sangster IT’S THE ROOKIE HUDDLE! offered to a singer who can’t/shouldn’t sing a certain role. What The Fach?! Let’s break that down a little more! Character What if we told you that SOPRANO, ALTO, TENOR, BASS Opera is all about telling stories. Sets, costumes, and lights is just the beginning of the types of voices wandering this give us information about time and place. The narrative planet. There are SO MANY VOICES! In this installation of and emotional details of the story are found in the music the Rookie Huddle we’ll talk about how opera singers – and as interpreted by the orchestra and singers. The singers are the people who hire them – rely on a system of transformed with wigs, makeup, and costumes, but their classification called Fach, which breaks those categories into characters are really found in the voice. many more specific parts. -

Voice Types in Opera

Voice Types in Opera In many of Central City Opera’s educational programs, we spend some time explaining the different voice types – and therefore character types – in opera. Usually in opera, a voice type (soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor, baritone, or bass) has as much to do with the SOUND as with the CHARACTER that the singer portrays. Composers will assign different voice types to characters so that there is a wide variety of vocal colors onstage to give the audience more information about the characters in the story. SOPRANO: “Sopranos get to be the heroine or the princess or the opera star.” – Eureka Street* “Sopranos always get to play the smart, sophisticated, sweet and supreme characters!” – The Great Opera Mix-up* A soprano is a woman’s voice type. There are many different kinds of sopranos within the general category: coloratura, lyric, and spinto are a few. Coloratura soprano: Diana Damrau as The Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute (Mozart): https://youtu.be/dpVV9jShEzU Lyric soprano: Mirella Freni as Mimi in La bohème (Puccini): https://youtu.be/yTagFD_pkNo Spinto soprano: Leontyne Price as Aida in Aida (Verdi): https://youtu.be/IaV6sqFUTQ4?t=1m10s MEZZO SOPRANO: “There are also mezzos with a lower, more exciting woman’s voice…We get to be magical or mythical characters and sometimes… we get to be boys.” – Eureka Street “Mezzos play magnificent, magical, mysterious, and miffed characters.” – The Great Opera Mix-up A mezzo soprano is a woman’s voice type. Just like with sopranos, there are different kinds of mezzo sopranos: coloratura, lyric, and dramatic. -

A Comparison of the Alto Voice in Early and Modern Opera

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk • w #*>* brought to you by CORE provided.'V by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship... J HUTCHINS A Comparison of the Alio Voice in Early mii Modern Opera j A ' Tw V ill, .^ i%V** i i • i ! 1 i i 4 Music j • 19 15 i • * THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/comparisonofaltoOOhutc COMPARISON OF THE ALTO VOICE IN EARLY AND MODERN OPERA BY MARJORIE HUTCHINS THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1915 , ftfy UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June I 19235. SUPERVISION BY THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY MARJORIS HUTCHIUS, - MODERN ENTITLED A COMPARISON OF THE ALTO VOICE IN EARLY JJffl OPERA, - - FOR THE IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS DEGREE QF BACHELOR OF MUSIC. , Instructor in Charge 1 IG HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF .S • u»uc H^T A COMPARISON OP THE ALTO VOICE IN EARLY AND MODERN OPERA. The alto voice is, in culture and use, as an important solo instrument, comparatively modern. It must be well understood that the alto voice, due to its harmonic relation to the soprano, has always been the secondary voice. The early opera writers, such as Monteverde, Cavalli, Lully, and Scarlatti, although they wrote for this voice when it was sung only by the male artificial con- tralli or counter-tenor, have done much toward putting it where it is today. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

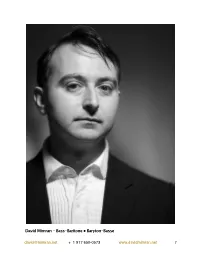

Bass-Baritone • Baryton-Basse [email protected] + 1 917 650-0573 1 100 Words Bio

David Mimran - Bass-Baritone • Baryton-Basse [email protected] + 1 917 650-0573 www.davidmimran.net 1 100 words bio Bass-Baritone David Mimran set aside a career as a lawyer in Paris to sing opera in New York. Great vocal flexibility in a wide tessitura, natural acting skills and a knowledge of nine languages including Italian, French, German, English, Spanish and Finnish allow for a large variety of repertoire. Roles on stage include Alcindoro/Benoît in Bohème, Conte Ceprano in Rigoletto, Niejus & Cascada in Merry Widow, Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte, Figaro & Antonio in Le nozze di Figaro, Morales & Zuniga in Carmen, Fiorello in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Frank in Fledermaus, Lorenzo in I Capuletti e i Montecchi, Achille in Giulio Cesare and Melisso in Alcina. Languages French: Mother tongue English: Bilingual German, Italian, Spanish: Proficient Finnish, Portuguese, Hebrew: Working knowledge Russian, Hungarian: Basic phonetic reading knowledge I would consider studying a new language to sing a role. Stage Experience Full roles performed • Benoît/Alcindoro in Bohème - Opera Company of Brooklyn • Sciarrone/Jailer in Tosca - Regina Opera • Yakuside in Madama Butterfly - Bleecker Street Opera • Niejus and Cascada in The Merry Widow - Amore Opera • Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte - NY Lyric Opera Theater • Fiorello in Il Barbiere di Siviglia - Bleecker Street Opera • Lorenzo in I Capuletti e i Montecchi - Manhattan Chamber Opera • Spinelloccio/Nicolao in Gianni Schicchi - Regina Opera • Achilla in Giulio Cesare - Manhattan Chamber Opera • Docteur -

A Guide to Vibrato & Straight Tone

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The Versatile Singer: A Guide to Vibrato & Straight Tone Danya Katok The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1394 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE VERSATILE SINGER: A GUIDE TO VIBRATO & STRAIGHT TONE by DANYA KATOK A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2016 ©2016 Danya Katok All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Date L. Poundie Burstein Chair of the Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Philip Ewell, advisor Loralee Songer, first reader Stephanie Jensen-Moulton L. Poundie Burstein Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract THE VERSATILE SINGER: A GUIDE TO VIBRATO & STRAIGHT TONE by Danya Katok Advisor: Philip Ewell Straight tone is a valuable tool that can be used by singers of any style to both improve technical ideals, such as resonance and focus, and provide a starting point for transforming the voice to meet the stylistic demands of any genre. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Bel Canto: the Teaching of the Classical Italian Song-Schools, Its Decline and Restoration

Performance Practice Review Volume 3 Article 9 Number 1 Spring "Bel canto: The eT aching of the Classical Italian Song-Schools, Its Decline and Restoration" By Lucie Manén Philip Lieson Miller Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Miller, Philip Lieson (1990) ""Bel canto: The eT aching of the Classical Italian Song-Schools, Its Decline and Restoration" By Lucie Manén," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 3: No. 1, Article 9. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199003.01.9 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol3/iss1/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reviews 97 Lucie Manen. Bel canto; The Teaching of the Classical Italian Song- Schools, Its Decline and Restoration. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. bibliography, 75p. Bel canto, it is generally agreed, is a lost art. But what, precisely, was bel canto? The word is used to describe the singing of the great castrati, and the repertory of classic Italian airs is known as bel canto music; the term conies up again to cover the operas of Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini and the school of singers trained to sing them. But Philip A. Duey, in his study of the subject, states: "The term Bel Canto does not appear as such during the period with which it is most often associated, i.e., the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; this may be said with finality." Lucie Manen as a singer was a casualty of World War II. -

The Voice and Singing Sample Pages.Pdf

2 THE VOICE AND SINGING FRANCIS KEEPING AND ROBERTA PRADA Originally LA VOIX ET LE CHANT TRAITÉ PRACTIQUE J. FAURE PARIS 1886 this book, translated and expanded contains Faure’s original exercises with all the transpositions as indicated by the author. 3 Copyright © 2005 Francis Keeping and Roberta Prada. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. Published in 2005 by Vox Mentor LLC. For sales please contact: Vox Mentor LLC. 343 East 30th street, 12M. New York, NY. 10016 phone: 212-684-5485 Email: [email protected] Website: www.voxmentor.biz Printed in USA. Awaiting Library of congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data ISBN 10: 0-9777823-0-1 Originally La Voix et le Chant, J. Faure, Paris, 1886, AU Menestrel, 2 bis, Rue Vivienne, Henri Heugel. The present volume is set in Times New Roman 12 point, on 28 lb. bright white acid free paper and wire bound for easy opening on the music stand. Page turns have been avoided wherever possible in the exercises, meaning that there are intentional blank spaces throughout. The cover photo of J. Faure as a younger man is from the collection of Bill Ecker of Harmonie Autographs, New York City. The present authors have faithfully translated the words of Faure, taking care to preserve the original intent of the author making changes only where necessary to assist modern readers. The music was written using Sibelius 3 and 4™ software. -

The Baroque. 3.3: Vocal Music: the Da Capo Aria and Other Types of Arias

UNIT 3: THE BAROQUE. 3.3: VOCAL MUSIC: THE DA CAPO ARIA AND OTHER TYPES OF ARIAS EXPLANATION 3.3: THE DA CAPO ARIA AND OTHER TYPES OF ARIAS. THE ARIA The aria in the operas is the part sung by the soloist. It is opposed to the recitative, which uses the recitative style. In the arias the composer shows and exploits the dramatic and emotional situations, it becomes the equivalent of a soliloquy (one person speach) in the spoken plays. In the arias, the interpreters showed their technique, they showed off, even in excess, which provoked a lot of criticism from poets and musicians. They were often sung by castrati: soprano men undergoing a surgical operation so as not to change their voice when they grew up. One of them, the most famous, Farinelli, acquired international fame for his great technique and vocal expression. He lived twenty-five years in Spain. THE DA CAPO ARIA The Da Capo aria is a vocal work in three parts or sections (tripartite form). It began to be used in the Baroque in operas, oratorios and cantatas. The form is A - B - A, the last part being a repetition of the first. 1. The first section is a complete musical entity, that is to say, it could be sung alone and musically it would have complete meaning since it ends in the tonic. The tonic is the first grade or note of a scale. 2. The second section contrasts with the first section in tonality, texture, mood and sometimes in tempo (speed). 3. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and