Citizen-Led Participation in Ontario Policy-Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mhtml:File://J:\Mediaclips\Mediaclips 2008\Mediaclips\The Cape Breton Post Editorial

The Cape Breton Post: Editorial | Apology policy goes sour Page 1 of 2 EDITORIAL Post a comment | View comments (1) | Last updated at 11:52 PM on 10/08/08 Apology policy goes sour The Cape Breton Post The bloom has faded from the rose of apology for Canada’s prime minister. The highlight came on June 11 when Stephen Harper, with a catch in his voice, delivered in the House of Commons the Statement of Apology on behalf of Canada to aboriginal victims of residential schools. That set a new benchmark for official contrition, never to be surpassed. What’s more, the statement came as part of a process that also established an Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission as part of $2 billion settlement reached among government, churches and representatives of some 90,000 former students. As a gesture of redress, all this would be a hard act to follow, and that’s a big problem with it in the view of anti-apologists. Critics such as The Globe and Mail’s Jeffrey Simpson, who refers derisively to “the apology industry,” don’t deny that aboriginal people have suffered grievously through government policy and that terrible wrongs were committed in the residential school system. But they hold to the view of a former prime minister, Pierre Trudeau, who believed we can be just only in our own time and official apologies for historic wrongs open the door to endless demands to acknowledge group grievances of the past. By this view, the problem with apologies is well illustrated in Harper’s experience the weekend before last when he delivered an apology to an Indo-Canadian audience in Surrey, B.C., on behalf of Parliament for Canada’s behaviour in the Komagata Maru incident of 1914. -

A Film by Chris Hegedus and D a Pennebaker

a film by Chris Hegedus and D A Pennebaker 84 minutes, 2010 National Media Contact Julia Pacetti JMP Verdant Communications [email protected] (917) 584-7846 FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building, 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] PRAISE FOR KINGS OF PASTRY “The film builds in interest and intrigue as it goes along…You’ll be surprised by how devastating the collapse of a chocolate tower can be.” –Mike Hale, The New York Times Critic’s Pick! “Alluring, irresistible…Everything these men make…looks so mouth-watering that no one should dare watch this film on even a half-empty stomach.” – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times “As the helmers observe the mental, physical and emotional toll the competition exacts on the contestants and their families, the film becomes gripping, even for non-foodies…As their calm camera glides over the chefs' almost-too-beautiful-to-eat creations, viewers share their awe.” – Alissa Simon, Variety “How sweet it is!...Call it the ultimate sugar high.” – VA Musetto, The New York Post “Gripping” – Jay Weston, The Huffington Post “Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker turn to the highest levels of professional cooking in Kings of Pastry,” a short work whose drama plays like a higher-stakes version of popular cuisine-oriented reality TV shows.” – John DeFore, The Hollywood Reporter “A delectable new documentary…spellbinding demonstrations of pastry-making brilliance, high drama and even light moments of humor.” – Monica Eng, The Chicago Tribune “More substantial than any TV food show…the antidote to Gordon Ramsay.” – Andrea Gronvall, Chicago Reader “This doc is a demonstration that the basics, when done by masters, can be very tasty.” - Hank Sartin, Time Out Chicago “Chris Hegedus and D.A. -

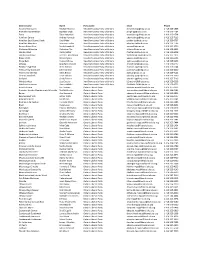

District Name

District name Name Party name Email Phone Algoma-Manitoulin Michael Mantha New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1938 Bramalea-Gore-Malton Jagmeet Singh New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1784 Essex Taras Natyshak New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0714 Hamilton Centre Andrea Horwath New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-7116 Hamilton East-Stoney Creek Paul Miller New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0707 Hamilton Mountain Monique Taylor New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1796 Kenora-Rainy River Sarah Campbell New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2750 Kitchener-Waterloo Catherine Fife New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6913 London West Peggy Sattler New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6908 London-Fanshawe Teresa J. Armstrong New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1872 Niagara Falls Wayne Gates New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 212-6102 Nickel Belt France GŽlinas New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-9203 Oshawa Jennifer K. French New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0117 Parkdale-High Park Cheri DiNovo New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0244 Timiskaming-Cochrane John Vanthof New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2000 Timmins-James Bay Gilles Bisson -

The Origins and Impact of Environmental Conflict Ideas

STRATEGIC SCARCITY: THE ORIGINS AND IMPACT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONFLICT IDEAS Elizabeth Hartmann Development Studies Institute London School of Economics and Political Science Submitted for the degree of PhD 2002 1 UMI Number: U615457 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615457 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 rM£ S£S F 20 ABSTRACT Strategic Scarcity: The Origins and Impact of Environmental Conflict Ideas Elizabeth Hartmann This thesis examines the origins and impact of environmental conflict ideas. It focuses on the work of Canadian political scientist Thomas Homer-Dixon, whose model of environmental conflict achieved considerable prominence in U.S. foreign policy circles in the 1990s. The thesis argues that this success was due in part to widely shared neo-Malthusian assumptions about the Third World, and to the support of private foundations and policymakers with a strategic interest in promoting these views. It analyzes how population control became an important feature of American foreign policy and environmentalism in the post-World War Two period. It then describes the role of the "degradation narrative" — the belief that population pressures and poverty precipitate environmental degradation, migration, and violent conflict — in the development of the environment and security field. -

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY Ajax Joe Dickson Liberal Stephen

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY Ajax Joe Dickson Liberal Stephen Leahy Green Rod Phillips PC Monique Hughes NDP Algoma—Manitoulin Charles Fox Liberal Justin Tilson Green Jib Turner PC Michael Mantha NDP Aurora - Oak Ridges - Richmond Hill Naheed Yaqubian Liberal Stephanie Nicole Duncan Green Michael Parsa PC Katrina Sale NDP Barrie-Innisfil Bonnie North Green Pekka Reinio NDP Andrea Khanjin PC Ann Hoggarth Liberal Barrie-Springwater-Oro-Medonte Keenan Aylwin Green Jeff Kerk Liberal Doug Downey PC Dan Janssen NDP Bay of Quinte Robert Quaiff Liberal Mark Daye Green Todd Smith PC Joanne Belanger NDP Beaches—East York Rima Berns-McGown NDP Arthur Potts Liberal Debra Scott Green Sarah Mallo PC Brampton Centre Safdar Hussain Liberal Laila Zarrabi Yan Green Harjit Jaswal PC Sara Singh NDP Brampton East Dr. Parminder Singh Liberal Raquel Fronte Green Sudeep Verma PC Gurratan Singh NDP Brampton North Harinder Malhi Liberal Pauline Thornham Green Ripudaman Dhillon PC Kevin Yarde NDP Brampton South Sukhwant Thethi Liberal Lindsay Falt Green Prabmeet Sarkaria PC Paramjit Gill NDP Brampton West Vic Dhillon Liberal Julie Guillemet-Ackerman Green Amarjot Sandhu PC Jagroop Singh NDP Brantford - Brant Ruby Toor Liberal Ken Burns Green Will Bouma PC Alex Felsky NDP Bruce—Grey—Owen Sound Elizabeth Marshall Trillium Francesca Dobbyn Liberal Don Marshall Green Karen Gventer NDP Bill Walker PC Burlington Jane McKenna PC Eleanor McMahon Liberal Andrew Drummond NDP Vince Fiorito Green Cambridge Kathryn McGarry Liberal Michele Braniff Green Belinda Karahalios PC Marjorie -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Government of Ontario Key Contact Ss

GOVERNMENT OF ONTARIO 595 Bay Street Suite 1202 Toronto ON M5G 2C2 KEY CONTACTS 416 586 1474 enterprisecanada.com PARLIAMENTARY MINISTRY MINISTER DEPUTY MINISTER PC CRITICS NDP CRITICS ASSISTANTS Steve Orsini Patrick Brown (Cabinet Secretary) Steve Clark Kathleen Wynne Andrea Horwath Steven Davidson (Deputy Leader + Ethics REMIER S FFICE Deb Matthews Ted McMeekin Jagmeet Singh P ’ O (Policy & Delivery) and Accountability (Deputy Premier) (Deputy Leader) Lynn Betzner Sylvia Jones (Communications) (Deputy Leader) Lorne Coe (Post‐Secondary ADVANCED EDUCATION AND Han Dong Peggy Sattler Education) Deb Matthews Sheldon Levy Yvan Baker Taras Natyshak SKILLS DEVELOPMENT Sam Oosterhoff (Digital Government) (Digital Government) +DIGITAL GOVERNMENT (Digital Government) AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS Jeff Leal Deb Stark Grant Crack Toby Barrett John Vanthof +SMALL BUSINESS ATTORNEY GENERAL Yasir Naqvi Patrick Monahan Lorenzo Berardinetti Randy Hillier Jagmeet Singh Monique Taylor Gila Martow (Children, Jagmeet Singh HILDREN AND OUTH ERVICES Youth and Families) C Y S Michael Coteau Alex Bezzina Sophie Kiwala (Anti‐Racism) Lisa MacLeod +ANTI‐RACISM Jennifer French (Anti‐Racism) (Youth Engagement) Jennifer French CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION Laura Albanese Shirley Phillips (Acting) Shafiq Qaadri Raymond Cho Cheri DiNovo (LGBTQ Issues) Lisa Gretzky OMMUNITY AND OCIAL ERVICES Helena Jaczek Janet Menard Ann Hoggarth Randy Pettapiece C S S (+ Homelessness) Matt Torigian Laurie Scott (Community Safety) (Community Safety) COMMUNITY SAFETY AND Margaret -

This Paper Seeks to Expand the Scope of These Two Seemingly Separate

Provincial-International Relations: Exploring the International Involvement of the Ontario Legislature Natalie Tutunzis, Ontario Legislature Internship Programme This paper seeks to explore the international involvement, or the international relations, of the Ontario Legislature. It will be shown that local parliamentarians, as exemplified by the involvement of the Ontario Legislature, have important roles to play internationally. Not only do provincial-international relations exist at the legislative level, but they occur quite frequently and in a diverse manner of ways. The paper will outline and describe such relations as they occur between the Ontario Legislature and foreign legislatures or other bodies, as exemplified through the Legislature’s involvement in interparliamentary organizations and delegations, as well as through the pursuit of international initiatives advanced by members, Officers, and affiliates of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. In addition to describing the actions that have and are currently taking place, the paper will begin a discussion about the general purposes of such international relations at the provincial parliamentary level, as well as discuss their perceived effectiveness. It will be argued that these relations have distinct purposes, which have, in many cases, achieved positive results. While literature on provincial-international legislative relations does exist, it is still remains quite sparse. However, the limited background that does exists on the matter nonetheless points to how frequently such relations occur, their significance, and even more so, how worthy they are of further exploration. Overall, this paper attempts to expand on the existing literature by providing an up-to-date account of the international involvement of provincial parliaments, using the Ontario Legislature as its case study. -

The Historian-Filmmaker's Dilemma: Historical Documentaries in Sweden in the Era of Häger and Villius

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Historica Upsaliensia 210 Utgivna av Historiska institutionen vid Uppsala universitet genom Torkel Jansson, Jan Lindegren och Maria Ågren 1 2 David Ludvigsson The Historian-Filmmaker’s Dilemma Historical Documentaries in Sweden in the Era of Häger and Villius 3 Dissertation in History for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy presented at Uppsala University in 2003 ABSTRACT Ludvigsson, David, 2003: The Historian-Filmmaker’s Dilemma. Historical Documentaries in Sweden in the Era of Häger and Villius. Written in English. Acta Universitatis Upsalien- sis. Studia Historica Upsaliensia 210. (411 pages). Uppsala 2003. ISSN 0081-6531. ISBN 91-554-5782-7. This dissertation investigates how history is used in historical documentary films, and ar- gues that the maker of such films constantly negotiates between cognitive, moral, and aes- thetic demands. In support of this contention a number of historical documentaries by Swedish historian-filmmakers Olle Häger and Hans Villius are discussed. Other historical documentaries supply additional examples. The analyses take into account both the produc- tion process and the representations themselves. The history culture and the social field of history production together form the conceptual framework for the study, and one of the aims is to analyse the role of professional historians in public life. The analyses show that different considerations compete and work together in the case of all documentaries, and figure at all stages of pre-production, production, and post-produc- tion. But different considerations have particular inuence at different stages in the produc- tion process and thus they are more or less important depending on where in the process the producer puts his emphasis on them. -

Privacy Included: Rethinking the Smart Home

Internet Health Report *Privacy Included: Rethinking the Smart Home Special Edition November 2019 1 Internet Health Report Special Edition Internet Health Report *Privacy Included: Rethinking the Smart Home Special Edition November 2019 2 Internet Health Report Special Edition Credits Editorial team: Solana Larsen, Sam Burton, Kasia Odrozek, Stefan Back, Jairus Khan Illustrations: Xenia Latii Print design: Agency of None Thank you to all the topic experts and allies from a wide variety of disciplines who generously contributed ideas to this publication through interviews and in writing. Stefan Baack, Owen Bennett, Cathleen Berger, Peter Bihr, Ashley Boyd, Lyall Bruce, Georgia Bullen, Sam Burton, Jen Caltrider, Bofu Chen, Irvin Chen, Kelly Davis, Selena Deckelmann, Ame Elliott, Felipe Fonseca, Ben Francis, Kathy Giori, Tony Gjerulfsen, Davide Gomba, Max von Grafenstein, Lisa Gutermuth, Jofish Kaye, Jairus Khan, Solana Larsen, Xenia Latii, Ben Moskowitz, Kasia Odrozek, Steve Penrod, Abigail Phillips, Bobby Richter, Becca Ricks, Chris Riley, Jon Rogers, Christiane Ruetten, Nicole Shadowen, Genia Shipova, Kevin Su, Peyton Sun, Mark Surman, James Teh, Michelle Thorne, Sofia Yan, Tammy Yang, Sarah Zatko Copyright Rights and Permissions: This work is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), excluding the six product images displayed on pages 9, 13, and 13, which are owned by third parties. Under this license, you are free to copy, redistribute, and adapt the material, even commercially, under the following terms: Attribution — Please cite this work as follows: Mozilla, Internet Health Report *Privacy Included: Rethinking the smart home. CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) Adaptations — If you remix, transform, or build upon this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: “This is an adaptation of an original work by Mozilla. -

Deanna Okun-Nachoff (’02)

It is not all nuts and bolts and statutes and court appearances, translate into reality for people? I’m able to get a glimpse of however. whether justice is working. I try to do my part to try to ensure that there’s some access to justice for the women I’m working with,” “Sometimes the most important thing is that the woman is being says Prince. “Unfortunately, my experience here is that there are heard. Being listened to and also believed. To feel supported is differing levels of justice. I don’t think the women I work with sometimes the most important thing, and that’s been a big lesson have the same access to justice as those who are less marginalized. for me,” Prince says. Within an organization like Atira, the lines It’s a great challenge and I try to bridge that gap.” between responsibilities are often blurred. “I find it difficult to compartmentalize aspects of a woman’s life. It’s her life,” she Originally from Prince George, BC , and a member of the Sucker explains. “It’s not, ‘this part is legal, this is counseling, this is housing.’ Creek First Nation in Enilda, Alberta, Prince began her education We build relationships with particular women, and they trust with a degree in criminology. Convinced she was not cut out to us for certain reasons, and then we help them with everything.” be a police officer, she moved on to law school at the University of British Columbia. Together with her master’s degree, her Working on the frontlines in the fight for access to justice, Prince education has given her the skills and expertise needed to help sees first-hand how justice is applied to marginalized members of clients navigate the legal system. -

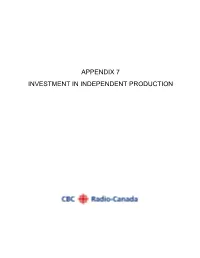

Appendix 7 Investment in Independent Production

APPENDIX 7 INVESTMENT IN INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION ABRIDGED Appendix 7 - Expenditures on Programming and Development on Independent Productions in Quebec (Condition of licence 23) CBC English Television 2019-2020 SUMMARY Programming Expenditure* All Independents* Quebec independents Percentage 131,425,935 5,895,791 4.5% Development Expenditures All Independents Quebec independents Percentage #### #### 8.5% Note: * Expenses as shown in Corporation's Annual Reports to the Commission, line 5 (Programs acquired from independent producers), Direct Operation Expenses section. Appendix 7-Summary Page 1 ABRIDGED APPENDIX 7 - CANADIAN INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION EXPENDITURES - DETAILED REPORT CBC English Television 2019-2020 Program Title Expenditures* Producer / Address Producer's Province A Cure For What Hails You - 2013 #### PYRAMID PRODUCTIONS 1 INC 2875 107th Avenue S.E. Calgary Alberta Alberta Digging in the Dirt #### Back Road Productions #102 – 9955 114th Street Edmonton Alberta Alberta Fortunate Son #### 1968 Productions Inc. 2505 17TH AVE SW STE 223 CALGARY Alberta Alberta HEARTLAND S 1-7 #### Rescued Horse Season Inc. 223, 2505 - 17th Avenue SW Calgary Alberta Alberta HEARTLAND S13 #### Rescued Horse Season Inc. 223, 2505 - 17th Avenue SW Calgary Alberta Alberta HEARTLAND X #### Rescued Horse Season Inc. 223, 2505 - 17th Avenue SW Calgary Alberta Alberta HEARTLAND XII #### Rescued Horse Season Inc. 223, 2505 - 17th Avenue SW Calgary Alberta Alberta Lonely #### BRANDY Y PRODUCTIONS INC 10221 Princess Elizabeth Avenue Edmonton, Alberta Alberta Narii - Love and Fatherhood #### Hidden Story Productions Ltd. 347 Sierra Nevada Place SW Calgary Alberta T3H3M9 Alberta The Nature Of Things - A Bee's Diary #### Bee Diary Productions Inc. #27, 2816 - 34 Ave Edmonton Alberta Alberta A Shine of Rainbows #### Smudge Ventures Inc.