Alberta Archaeological Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberta the Co-Founders of Ribstone Creek Brewery Have Brought a Value-Added Business Back to the Village Where They Grew Up

Fighting Fires Jerusalem OUT HERE, when the artichoke has HOMECOMING HAS A water is Frozen Feed and bioFuel DIFFERENT potential MEANING. » PAGE 13 » PAGE 23 Livestock checklist now available in-store and at UFA.com. Publications Mail Agreement # 40069240 110201353_BTH_Earlug_AFE_v1.indd 1 2013-09-16 4:46 PM Client: UFA . Desiree File Name: BTH_Earlug_AFE_v1 Project Name: BTH Campaign CMYK PMS ART DIR CREATIVE CLIENT MAC ARTIST V1 Docket Number: 110201353 . 09/16/13 STUDIO Trim size: 3.08” x 1.83” PMS PMS COPYWRITER ACCT MGR SPELLCHECK PROD MGR PROOF # Volume 10, number 23 n o V e m b e r 1 1 , 2 0 1 3 Farmer brews up big business in rural Alberta The co-founders of Ribstone Creek Brewery have brought a value-added business back to the village where they grew up the recently completed ribstone Creek brewery still has plenty of room to expand brewing capacity. Photo: Jennifer Blair Vice-president Chris fraser had “they basically said to him, ‘You to expand once to meet growing By Jennifer Blair seen some craft breweries along really don’t know what you’re demand for its lager. af staff / edgerton his travels, and as soon as he sug- doing, do you?’ and we had to “It was a nice problem to have, “Nothing quite gets gested it, the four co-founders — admit that we didn’t,” Paré said. when your demand outweighs on Paré’s plan to build Paré, fraser, Ceo Cal Hawkes, and the supplier put the group your production,” said Paré. “But people’s attention like a brewery in the heart of Cfo alvin gordon — knew they in touch with brewmaster and unfortunately, it does hurt you, when you say the word D rural alberta came about had hit upon the right idea. -

Corporate Registry Registrar's Periodical

Service Alberta ____________________ Corporate Registry ____________________ Registrar’s Periodical SERVICE ALBERTA Corporate Registrations, Incorporations, and Continuations (Business Corporations Act, Cemetery Companies Act, Companies Act, Cooperatives Act, Credit Union Act, Loan and Trust Corporations Act, Religious Societies’ Land Act, Rural Utilities Act, Societies Act, Partnership Act) 0767527 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1209706 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 01 Registered Address: 300- Registered 2019 NOV 07 Registered Address: SUITE 10711 102 ST NW , EDMONTON ALBERTA, 230, 2323 32 AVE NE, CALGARY ALBERTA, T5H2T8. No: 2122266683. T2E6Z3. No: 2122278068. 0995087 B.C. INC. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1221996 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 14 Registered Address: 10012 - Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 101 STREET, PO BOX 6210, PEACE RIVER - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. ALBERTA, T8S1S2. No: 2122287010. No: 2122268044. 10191787 CANADA INC. Federal Corporation 1221998 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 13 Registered Address: 4300 Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 BANKERS HALL WEST, 888 - 3RD STREET S.W., - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P 5C5. No: 2122287101. No: 2122268176. 102089241 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other 1221999 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 Registered Address: 101 - 1ST ST. EAST P.O. BOX - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. 210, DEWBERRY ALBERTA, T0B 1G0. No: No: 2122268259. 2122270461. 1222024 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 10632449 CANADA LTD. Federal Corporation Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 3400, 350 Registered 2019 NOV 04 Registered Address: 855 - 2 - 7TH AVENUE SW, CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3N9. -

Hotspot You Would Like to Visit Within Beaver County Daysland Property

Cooking Lake-Blackfoot Provincial Recreation Area Parkland Natural Area For Tips and Etiquette Francis Viewpoint of Nature Viewing Click “i” Above Tofield Nature Center Beaverhill Bird Observatory Ministik Lake Game Bird Sanctuary Earth Academy Park Viking Bluebird Trails Black Nugget Lake Park Click on the symbol of the Camp Lake Park nature hotspot you would like to visit within Beaver County Daysland Property Viking Ribstones Prepared by Dr. Glynnis Hood, Dr. Glen Hvenegaard, Dr. Anne McIntosh, Wyatt Beach, Emily Grose, and Jordan Nakonechny in partnership with the University of Alberta All photos property of Jordan Nakonechny unless otherwise stated Augustana Campus and the County of Beaver Return to map Beaverhill Bird Observatory The Beaverhill Bird Observatory was established in 1984 and is the second oldest observatory for migration monitoring in Canada. The observatory possesses long-term datasets for the purpose of analyzing population trends, migration routes, breeding success, and survivorship of avian species. The observatory is located on the edge of Beaverhill Lake, which was designated as a RASMAR in 1987. Beaverhill Lake has been recognized as an Important Bird Area with the site boasting over 270 species, 145 which breed locally. Just a short walk from the laboratory one can commonly see or hear white-tailed deer, tree swallows, yellow warblers, house wrens, yellow-headed blackbirds, red- winged blackbirds, sora rails, and plains garter snakes. For more information and directions visit: http://beaverhillbirds.com/ Return to map Black Nugget Lake Park Black Nugget Lake Park contains a campground of well-treed sites surrounding a human-made lake created from an old coal mine. -

AMENDMENT 002 Attn: Sìne Macadam GETS Reference No

Title – Sujet RETURN BIDS TO: Cemetery Maintenance for Alberta RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date Veterans Affairs Canada 3000726188 2021-06-17 Procurement & Contracting – AMENDMENT 002 Attn: Sìne MacAdam GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG [email protected] - File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME Time Zone AMENDMENT - REQUEST FOR Fuseau horaire Solicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Atlantic Daylight PROPOSAL at – à 2:00 PM Time on – le 2021-06-29 ADT MODIFICATION - DEMANDE DE F.O.B. - F.A.B. PROPOSITION Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions Buyer Id – Id de l’acheteur à: Sìne MacAdam Proposal To: Veterans Affairs Canada Telephone No. – N° de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX (902) 626-5288 N/A We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: right of Canada, in accordance with the terms and Destination – des biens, services et construction : conditions set out herein, referred to herein or See Herein attached hereto, the goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. Proposition aux: Anciens Combattants Canada Nous offrons par la présente de vendre à Sa Majesté la Reine du chef du Canada, aux conditions énoncées ou incluses par référence dans la présente et aux annexes ci-jointes, les biens, services et construction énumérés ici sur toute feuille ci-annexées, au(x) prix indiqué(s) Instructions: See Herein Instructions : Voir aux présentes Delivery required - Delivered Offered – Livraison proposée Comments - Commentaires Livraison exigée See Herein Vendor/firm Name and address This requirement contains a security requirement Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l’entrepreneur Vendor/Firm Name and address Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l’entrepreneur Facsimile No. -

St2 St9 St1 St3 St2

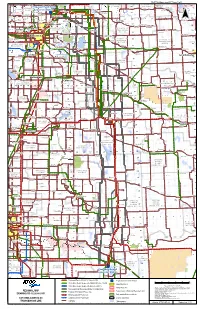

! SUPP2-Attachment 07 Page 1 of 8 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! .! ! ! ! ! ! SM O K Y L A K E C O U N T Y O F ! Redwater ! Busby Legal 9L960/9L961 57 ! 57! LAMONT 57 Elk Point 57 ! COUNTY ST . P A U L Proposed! Heathfield ! ! Lindbergh ! Lafond .! 56 STURGEON! ! COUNTY N O . 1 9 .! ! .! Alcomdale ! ! Andrew ! Riverview ! Converter Station ! . ! COUNTY ! .! . ! Whitford Mearns 942L/943L ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 56 ! 56 Bon Accord ! Sandy .! Willingdon ! 29 ! ! ! ! .! Wostok ST Beach ! 56 ! ! ! ! .!Star St. Michael ! ! Morinville ! ! ! Gibbons ! ! ! ! ! Brosseau ! ! ! Bruderheim ! . Sunrise ! ! .! .! ! ! Heinsburg ! ! Duvernay ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! 18 3 Beach .! Riviere Qui .! ! ! 4 2 Cardiff ! 7 6 5 55 L ! .! 55 9 8 ! ! 11 Barre 7 ! 12 55 .! 27 25 2423 22 ! 15 14 13 9 ! 21 55 19 17 16 ! Tulliby¯ Lake ! ! ! .! .! 9 ! ! ! Hairy Hill ! Carbondale !! Pine Sands / !! ! 44 ! ! L ! ! ! 2 Lamont Krakow ! Two Hills ST ! ! Namao 4 ! .Fort! ! ! .! 9 ! ! .! 37 ! ! . ! Josephburg ! Calahoo ST ! Musidora ! ! .! 54 ! ! ! 2 ! ST Saskatchewan! Chipman Morecambe Myrnam ! 54 54 Villeneuve ! 54 .! .! ! .! 45 ! .! ! ! ! ! ! ST ! ! I.D. Beauvallon Derwent ! ! ! ! ! ! ! STRATHCONA ! ! !! .! C O U N T Y O F ! 15 Hilliard ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! N O . 1 3 St. Albert! ! ST !! Spruce ! ! ! ! ! !! !! COUNTY ! TW O HI L L S 53 ! 45 Dewberry ! ! Mundare ST ! (ELK ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! . ! ! Clandonald ! ! N O . 2 1 53 ! Grove !53! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ISLAND) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ardrossan -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

Rockhounding North America

ROCKHOUNDING NORTH AMERICA Compiled by Shelley Gibbins Photos by Stefan and Shelley Gibbins California Sapphires — Montana *Please note that the Calgary Rock and Lapidary Quartz — Montana Club is not advertising / sponsoring these venues, but sharing places for all rock lovers. *Also, remember that rules can change; please check that these venues are still viable and permissible options before you go. *There is some risk in rockhounding, and preventative measures should be taken to avoid injury. The Calgary Rock and Lapidary Club takes no responsibility for any injuries should they occur. *I have also included some locations of interest, which are not for collecting Shells — Utah General Rules for Rockhounding (keep in mind that these may vary from place to place) ! • Rockhounding is allowed on government owned land (Crown Land in Canada and Bureau of Land Management in USA) ! • You can collect on private property only with the permission of the landowner ! • Collecting is not allowed in provincial or national parks ! • The banks along the rivers up to the high water mark may be rock hounded ! • Gold panning may or may not need a permit – in Alberta you can hand pan, but need a permit for sluice boxes ! • Alberta fossils are provincial property and can generally not be sold – you can surface collect but not dig. You are considered to be the temporary custodian and they need to stay within the province Fossilized Oysters — BC Canada ! Geology of Provinces ! Government of Canada. Natural resources Canada. (2012). Retrieved February 6/14 from http://atlas.gc.ca/site/ english/maps/geology.html#rocks. -

APS Bulletin June 1994

A L B E R T A • P A L A E O N T O L O G I C A L • S O C I E T Y VOLUME 9 NUMBER 2 JUNE 1994 1 ALBERTA PALAEONTOLOGICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS President Les Adler 289-9972 Program Coordinator Holger Hartmaier 938-5941 Vice-President Peter Meyer 289-4135 Curator Harvey Negrich 249-4497 Treasurer Roger Arthurs 279-5966 Librarian Gerry Morgan 241-0963 Secretary Don Sabo 249-4497 Field Trip Coordinator Les Fazekas 248-7245 Past-President Percy Strong 242-4735 Directors at Large Dr. David Mundy 281-3668 DIRECTORS Wayne Braunberger 278-5154 Editor Howard Allen 274-1858 APAC† Representative Don Sabo 249-4497 Membership Vaclav Marsovsky 547-0182 The Society was incorporated in 1986, as a non-profit organization formed to: a. Promote the science of palaeontology through study and education. b. Make contributions to the science by: 1) discovery 4) education of the general public 2) collection 5) preservation of material for study and the future 3) description c. Provide information and expertise to other collectors. d. Work with professionals at museums and universities to add to the palaeontological collections of the province (preserve Alberta’s heritage) MEMBERSHIP: Any person with a sincere interest in palaeontology is eligible to present their application for membership in the Society. Single membership $10.00 annually Family or Institution $15.00 annually THE BULLETIN WILL BE PUBLISHED QUARTERLY: March, June, September and December. Deadline for submitting material for publication is the 15th of the month prior to publication. Society Mailing Address: Material for Bulletin: Alberta Palaeontological Society Howard Allen, Editor, APS P.O. -

Updated Population of Places on the Alberta Road Map with Less Than 50 People

Updated Population of Places on the Alberta Road Map with less than 50 People Place Population Place Population Abee 25 Huallen 28 Altario 26 Hylo 22 Ardenode 0 Iddesleigh 14 Armena 35 Imperial Mills 19 Atikameg 22 Indian Cabins 11 Atmore 37 Kapasiwin 14 Beauvallon 7 Kathryn 29 Beaver Crossing 18 Kavanagh 41 Beaverdam 15 Kelsey 10 Bindloss 14 Keoma 40 Birch Cove 19 Kirkcaldy 24 Bloomsbury 18 Kirriemuir 28 Bodo 26 La Corey 40 Brant 46 Lafond 36 Breynat 22 Lake Isle 26 Brownfield 27 Larkspur 21 Buford 47 Leavitt 48 Burmis 32 Lindale 26 Byemoor 40 Lindbrook 18 Carcajou 17 Little Smoky 28 Carvel 37 Lyalta 21 Caslan 23 MacKay 15 Cessford 31 Madden 36 Chinook 38 Manola 29 Chisholm 20 Mariana Lake 8 Compeer 21 Marten Beach 38 Conrich 19 McLaughlin 41 Cynthia 37 Meeting Creek 42 Dalemead 32 Michichi 42 Dapp 27 Millarville 43 De Winton 44 Mission Beach 37 Deadwood 22 Mossleigh 47 Del Bonita 20 Musidora 13 Dorothy 14 Nestow 10 Duvernay 26 Nevis 30 Ellscott 10 New Bridgden 24 Endiang 35 New Dayton 47 Ensign 17 Nisku 40 Falun 25 Nojack 19 Fitzgerald 4 North Star 49 Flatbush 30 Notekiwin 17 Fleet 28 Onefour 31 Gadsby 40 Opal 13 Gem 24 Orion 11 Genesee 18 Peace Point 21 Glenevis 25 Peoria 12 Goodfare 11 Perryvale 20 Hairy Hill 46 Pincher 35 Heath 14 Pocahontas 10 Hilliard 35 Poe 15 Hoadley 9 Purple Springs 26 Hobbema 35 Queenstown 15 Page 1 of 2 Updated Population of Places on the Alberta Road Map with less than 50 People Rainier1 29 Star 32 Raven 12 Steen River 12 Red Willow 40 Streamstown 15 Reno 20 Sundance Beach 37 Ribstone 48 Sunnynook 13 Rich Valley 32 Tangent 39 Richdale 14 Tawatinaw 10 Rivercourse 14 Telfordville 28 Rowley 11 Tulliby Lake 18 St. -

Milk and Lower Marias River Watersheds: Assessing and Maintaining the Health of Wetland Communities

Milk and Lower Marias River Watersheds: Assessing and Maintaining the Health of Wetland Communities Prepared for: The Bureau of Reclamation By: W. Marc Jones Montana Natural Heritage Program Natural Resource Information System Montana State Library June 2003 Milk and Lower Marias River Watersheds: Assessing and Maintaining the Health of Wetland Communities Prepared for: The Bureau of Reclamation Agreement Number: 01 FG 601 522 By: W. Marc Jones 2003 Montana Natural Heritage Program P.O. Box 201800 • 1515 East Sixth Avenue • Helena, MT 59620-1800 • 406-444-3009 This prefered citation for this document is: Jones, W. M. 2003. Milk and Lower Marias River Watersheds: Assessing and Maintaining the Health of Wetland Communities. Report to the Bureau of Reclamation. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena. 17 pp. plus appendices. Table of Contents Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 Study Area ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Physical Setting ........................................................................................................................... 1 Vegetation and Ecological Processes .......................................................................................... 3 Methods.......................................................................................................................................... -

Tourism Drumheller 2016

DRUMHELLER days and days of discovery 3 May not be exactly to scale. Please refer to the official Alberta road map for precise and detailed information. CoNTENTS FEATURES Travel Drumheller ## ONLY IN DRUMHELLER Box 1357 Tucked into one of Alberta's most distinctive and Drumheller, AB T0J 0y0 P: 1-866-823-8100 intriguing areas, this town offers a number of unique [email protected] 6 experiences. www.traveldrumheller.com PROJECT CO#ORDINATORS EXPLORING DRUMHELLER ON FOOT Shelley Rymal The top-heavy hoodoos and furrowed slopes of the Julia Fielding Drumheller Valley amaze from afar, but nothing Debbie Schinnour 8 compares to the badlands from ground level. COVER PHOTO Darryl Reid, Natural Light Photography DESTINATION: DINOSAUR COUNTRY Uncover ancient mysteries at the Royal Tyrrell Museum PHOTOS of Palaeontology. Anne Allen 10 Bob Cromwell Julia Fielding, Atlas Coal Mine April Friesen Debra Jungling, Jungling Works DRUMHELLER, A HISTORY Chris mclellan, Canadian Badlands Darryl Reid, When coal was king, Drumheller boomed and a Natural Light Photography young man’s character was forged in the mines. Debbie Schinnour, 12 World’s Largest Dinosaur The Royal Tyrrell museum The Town of Drumheller Athena Winchester, Broken Curfew MINING THE PAST Journey into history at the Atlas Coal Mine. PUBLISHER 14 TNC Publishing Group SPOTLIGHTS: REGIONAL SALES MANAGER The Hamlet of WAyNE The BADlANDS Erwin Jack 18 22 20 The RoSEBuD CENTRE PASSIoN PlAy MARKETING DIRECTOR 24 The Village of DoRoTHy Brian Steel oF THE ARTS Natalie Skaley DEPARTMENTS MARKETING COORDINATOR Eva Stefansson 36 DRumHEllER’S DINING SCENE ACCOUNTING & Drumheller has a wealth of impressive dining options — ADMINISTRATION here's where to find them. -

POPULATION of BOW ISLAND 2025 People

The community of Bow Island received its first families in 1900. In February 1910, the village of Bow Island was formed and on February 1st of 1912 the village was declared the Town of Bow Island. The town of Bow Island was one of the first towns in the province of Alberta to have natural gas wells and operated them until the franchise was sold to a private company. The community of Bow Island suffered through the depression years, as did all the communities in Western Canada. In the early 1950’s irrigation was extended to the Bow Island area. The Town of Bow Island doubled in population when irrigation water finally flowed through the ditches. 110,000 acres of highly productive lands surround the Town of Bow Island. Some of the most modern irrigation systems in the world are located in the area. The first pivot sprinkler system in Canada was erected on a farm in close proximity to Bow Island in 1961. The first linear sprinkler systems in Canada were put in- to operation in the Bow Island area. A completely automated distribution system was installed in 1982 by the St. Mary’s River Irrigation District (SMRID) This system is known as the lateral 12 system and has been toured by groups from around the world. Bow Island has become a vibrant agricultural community with many agri-processing industries located here, such as: Bow Island Dry Edible Bean Plant and Alberta Sunflower Seeds Ltd. (SPITZ) TOWN OF BOW ISLAND The story has it that Bow Island was named for an island in a bend of “bow” in the South Saskatchewan River directly north of town, where river boats used to unload coal in the early years.