Alternative Chicks Fairplay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ski Magazine

THE SHOW MUST WITH FACE OF WINTER, WARREN MILLER ENTERTAINMENT KEEPS GO A BELOVED TRADITION ALIVE AND CONTINUES TO SPREAD WARREN’S ON GOSPEL OF SKIING. THIS FALL Warren Miller Entertainment debuts its 69th annual ski film, continuing a tradition that the late godfather of action-sports films started decades ago. Face of Winter promises to deliver all that WME ski flicks have become known for: jaw-dropping scenery, adrenaline-pumping ski action, and above all, an intimate look at the people and places that make skiing so rad. In the following pages, this year’s WME athletes and crew pay tribute to Warren, the original face of winter, and the entertainment legacy he Cinematographer Jeff Wright films Marcus Caston leaves behind. Since Warren would be the first to admit that he may have (left) and Johan Jonsson during the Engelberg, borrowed one (or many) of his famous, quirky one-liners, we thought it only Switzerland segment of Face of Winter. right to borrow Warren’s words in turn. After all, imitation is the sincerest PHOTO CREDIT PHOTO CREDIT ENANDER PHOTO OSKAR form of flattery. SKI MAGAZINE / 90 / NOVEMBER 2018 SKI MAGAZINE / 91 / NOVEMBER 2018 THE SHOW MUST GO ON IN THIS YEAR’S FILM... Mike Wiegele no longer appears in front of the WME camera but plays gracious host to the film crew and athletes while they shoot with Wiegele guides like Bob Sayer, featured in this year’s film. JONNY MOSELEY at Lake Louise, then made trips into the For the past decade, Jonny Moseley has one-piece ski suit while throwing a bunch of Cosacks and Iron-Cross mountains to explore. -

Rules for the Fis Freestyle Ski Continental Cup

RULES FOR THE FIS FREESTYLE SKI CONTINENTAL CUP EUROPEAN CUP NOR-AM CUP SOUTH AMERICAN CUP AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND CUP EDITION 2018/2019 - 1 - INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE SKI INTERNATIONALER SKI VERBAND Blochstrasse 2, CH- 3653 Oberhofen / Thunersee, Switzerland Telephone: +41 (33) 244 61 61 Fax: +41 (33) 244 61 71 Website: www.fis-ski.com Oberhofen, June 2018 - 2 - Section A Rules Applicable to all FIS Freestyle Ski Continental Cups Section A defines the FIS Continental Cup Rules that are interchangeable between all FIS Continental Cups worldwide. 1. General All events in the FIS Continental Cup Series will be conducted under the rules and regulations of the International Ski Federation (ICR and COC: Section A) and the respective National Ski Associations (Cup Rules: Section B). 1.1 Organisation 1.1.1 Jury (see ICR 3032) 1.1.1.1 At least one member of the Jury shall be from other than the host country. The FIS Coordinator for the Continental Cup series concerned (where present) shall take the role of the FIS Race Director as advisor to the Jury. 1.1.2 Technical Delegate The FIS Technical Delegate is required to arrive no less than the day prior to the start of Official Training. The FIS Technical Delegate is required to participate in the course inspection(s) with the Jury at least 1 day prior to the first day of competition. 2. Qualification Qualification standards The qualification standards and quotas will be established with the approval of the FIS Freestyle Skiing Committee. They cannot be modified during the season. -

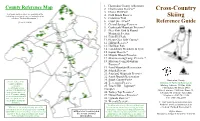

Cross-Country Skiing

1. Hunterdon County Arboretum County Reference Map 2. Charlestown Reserve* Cross-Country 3. Clover Hill Park Trail maps and brochures are available at the 4. Cold Brook Reserve Arboretum or online at www.co.hunterdon.nj.us Skiing (click on “Parks & Recreation”). 5. Columbia Trail (Revised 2/2020) 6. Court Street Park* Reference Guide 7. Crystal Springs Preserve 8. Cushetunk Mountain Preserve* 9. Deer Path Park & Round Mountain Section 10. Echo Hill Park 11. Heron Glen Golf Course* 12. Hilltop Reserve* 13. Hoffman Park 14. Landsdown Meadows & Trail 15. Laport Reserve* 16. Miquin Woods Preserve 17. Musconetcong Gorge Preserve* 18. Musconetcong Mountain Preserve* 19. Point Mountain Reservation 20. Schick Reserve 21. Sourland Mountain Preserve 22. South Branch Reservation 23. South County Park* Hunterdon County It is the policy of the County to provide 24. Teetertown Preserve Division of Parks & Recreation reasonable 25. Tower Hill—Jugtown* Mailing Address: PO Box 2900, accommodations to Flemington, NJ 08822-2900 persons with disabilities Complex Office Location: 1020 State Route 31, upon advance notice of 26. Turkey Top Preserve* Lebanon, NJ (Clinton Township) need. Persons requiring accommodations should 27. Union Furnace Preserve* Telephone: (908) 782-1158 make a request at least 2 28. Uplands Reserve* Fax: (908) 806-4057 weeks prior to program attendance. 29. Wescott Preserve E-mail: [email protected] The Hunterdon County Division of Parks and Website: www.co.hunterdon.nj.us With the exception of park properties with Recreation is dedicated to preserving open space (click on “Parks & Recreation”) reservable facilities, all properties are “carry in / and natural resources, providing safe parks and carry out” and trash/recycling receptacles are not *Skiing is not recommended. -

Perspectives of the Sport-Oriented Public in Slovenia on Extreme Sports

Rauter, S. and Doupona Topič, M.: PERSPECTIVES OF THE SPORT-ORIENTED ... Kinesiology 43(2011) 1:82-90 PERSPECTIVES OF THE SPORT-ORIENTED PUBLIC IN SLOVENIA ON EXTREME SPORTS Samo Rauter and Mojca Doupona Topič University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Sport, Ljubljana, Slovenia Original scientific paper UDC 796.61(035) (497.4) Abstract: The purpose of the research was to determine the perspectives of the sport-oriented people regarding the participation of a continuously increasing number of athletes in extreme sports. At the forefront, there is the recognition of the reasons why people actively participate in extreme sports. We were also interested in the popularity of individual sports and in people‘s attitudes regarding the dangers and demands of these types of sports. The research was based on a statistical sample of 1,478 sport-oriented people in Slovenia, who completed an online questionnaire. The results showed that people were very familiar with individual extreme sports, especially the ultra-endurance types of sports. The people who participated in the survey stated that the most dangerous types of sports were: extreme skiing, downhill mountain biking and mountaineering, whilst the most demanding were: Ironman, ultracycling, and ultrarunning. The results have shown a wider popularity of extreme sports amongst men and (particularly among the people participating in the survey) those who themselves prefer to do these types of sports the most. Regarding the younger people involved in the survey, they typically preferred the more dangerous sports as well, whilst the older ones liked the demanding sports more. People consider that the key reasons for the extreme athletes to participate in extreme sports were entertainment, relaxation and the attractiveness of these types of sports. -

Physical Testing Characteristics and Technical Event Performance of Junior Alpine Ski Racers David Heikkinen

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2003 Physical Testing Characteristics and Technical Event Performance of Junior Alpine Ski Racers David Heikkinen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Kinesiology Commons Recommended Citation Heikkinen, David, "Physical Testing Characteristics and Technical Event Performance of Junior Alpine Ski Racers" (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 473. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/473 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. PHYSICAL TESTING CHARACTERISTICS AND TECHNICAL EVENT PERFORMANCE OF JUNIOR ALPINE SKI RACERS By David Heikkinen B.S. University of Maine at Farmington, 1998 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (in Kinesiology and Physical Education) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2003 Advisory Committee: Robert Lehnhard, Associate Professor of Education, Advisor Phil Pratt, Cooperative Associate Education Stephen Butterfield, Professor of Education and Special Education PHYSICAL TESllNG CHARACTERlSllCS AND TECHNICAL EVENT PERFORNlANCE OF JUNIOR ALPlNE SKI RACERS By David Heikkinen Thesis Advisor: Dr. Robert Lehnhard An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (in Kinesiology and Physical Education) May, 2003 The purpose of this study was to determine if a battery of physical tests can be used to distinguish between the ability levels of junior alpine ski racers. Many sports, such as football, have established laboratory and field tests to assess their athlete's preparation for competition. -

2017/18 Steamboat Press Kit

2017/18 Steamboat Press Kit TABLE OF CONTENTS What’s new this winter at Steamboat ............................................................... Pages 2-3 New ownership, additional nonstop flights, mountain coaster, gondola upgrades Expanded winter air program ........................................................................... Pages 4-5 Fly nonstop into Steamboat from 14 major U.S. airports. New this year: Austin, Kansas City Winter Olympic tradition ................................................................................ Pages 6-10 Steamboat has produced 89 winter Olympians, more than any other town in North America. Champagne Powder® snow ............................................................................ Pages 11-14 Family programs ............................................................................................. Pages 15-17 Mountain facts and statistics ......................................................................... Pages 18-21 History of Steamboat ...................................................................................... Pages 22-30 Events calendar .............................................................................................. Pages 31-34 Cowboy Downhill ............................................................................................ Pages 35-38 Night skiing and snowboarding ..................................................................... Pages 39-40 On-mountain dining and Steamboat’s top restaurants ............................... Pages 41-48 -

December 2010 - February 2011 Ably Increased

Skiing | Running | Hiking | Biking Paddling | Triathlon | Fitness | Travel FREE! DECEMBER 20,000 CIRCULATION CAPITAL REGION • SARATOGA • GLENS FALLS • ADIRONDACKS 2010 bra ele ti C n g ASF HAVING FUN DURING THE CAMP SARATOGA 8K SNOWSHOE RACE AT THE WILTON WILDLIFE PRESERVE AND PARK IN 2009. PHOTO BY BRIAN TEAGUE Visit Us on the Web! AdkSports.com 2011 SNOWSHOE RACING SEASON by Laura Clark CONTENTS Back to the Future n the Stephen Spielberg trilogy, Back to the Future, a played with all the neighborhood children, albeit in boots, Iteenager travels through time and must correct the and I can’t help but wonder if she had seen it snowshoed ARTICLES & FEATURES results of his interference, lest his present become mere when she was a girl. 1 Running & Walking speculation. While for now this remains mere conjecture, Closer to the spirit of the Northeast’s 2011 Dion it is interesting to note how fluid past, present, and future Snowshoe Series at dionsnowshoes.com for runners and 2011 Snowshoe Racing Preview are even in a pre-time travel era. walkers, however, were New England’s early snowshoe 3 Cross-Country Skiing We all know that prehistoric migrants crossed the clubs. Participants would meet once or twice a week with & Snowshoeing Bering Sea on snowshoes, that early French explorers a different member responsible for selecting the route. At raquetted their way to North American fur trade empires, the halfway mark they would stop at a farmhouse or inn Nordic Ski Centers Ready for Season and that Rogers’ Rangers, the original Special Forces unit, for supper and then hike back by a different path, pref- 9 Alpine Skiing & Snowboarding achieved enviable winter snowshoe maneuverability in erably one which included a fun downhill slide. -

Cross Country Skiing, Curling, Freesking and Snowboarding Taking Place at Venues Across the Otago Region of New Zealand’S South Island

CROSS 20 - 31 August 2015 COUNTRY SKIING INVITATION AUGUST 2015 Dear Cross Country Ski Racing Nations, We are delighted to invite all nations to the FIS Cross Country Ski Racing Australia New Zealand Continental Cup Races, which will take place at Snow Farm NZ. These events are part of the Audi quattro Winter Games New Zealand, an international biennial winter sports event based in Otago, NZ. The 2015 edition of the Audi quattro Winter Games NZ will take place over an 10 day period from the 21st - 30th August and will feature elite winter sports competitions in Alpine Skiing, Cross Country Skiing, Curling, Freesking and Snowboarding taking place at venues across the Otago region of New Zealand’s South Island. The FIS Cross Country Ski Racing Australia New Zealand Continental Cup Races will be hosted at Snow Farm NZ. The nearest township is Wanaka (34km, 35 minute drive). The nearest major airport, Queenstown, is 50km (50 minute drive). Entries for the FIS Cross Country Ski Racing Australia New Zealand Continental Cup Races are open now via the our online FIS form. Please find the athlete and team information below. For further information please contact Nikki Holmes, Cross Country Skiing Manager on [email protected] We look forward to welcoming you to Queenstown and the Audi quattro Winter Games NZ. Kind regards Arthur Klap Chief Executive, Winter Games NZ Invitation contents The 4th edition of the Dates and Venues 4 Entry fees 7 Race Notice 5 Eligibility 7 Audi quattro Winter Race Organising Committee 5 Opening Ceremony 7 Games -

Freestyle/Freeskiing Competition Guide

Insurance isn’t one size fits all. At Liberty Mutual, we customize our policies to you, so you only pay for what you need. Home, auto and more, we’ll design the right policy, so you’re not left out in the cold. For more information, visit libertymutual.com. PROUD PARTNER Coverage provided and underwritten by Liberty Mutual Insurance and its affiliates, 175 Berkeley Street, Boston, MA 02116 USA. ©2018 Liberty Mutual Insurance. 2019 FREESTYLE / FREESKIING COMPETITION GUIDE On The Cover U.S. Ski Team members Madison Olsen and Aaron Blunck Editors Katie Fieguth, Sport Development Manager Abbi Nyberg, Sport Development Manager Managing Editor & Layout Jeff Weinman Cover Design Jonathan McFarland - U.S. Ski & Snowboard Creative Services Published by U.S. Ski & Snowboard Box 100 1 Victory Lane Park City, UT 84060 usskiandsnowboard.org Copyright 2018 by U.S. Ski & Snowboard. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the USA by RR Donnelley. Additional copies of this guide are available for $10.00, call 435.647.2666. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Key Contact Directory 4 Divisional Contacts 6 Chapter 1: Getting Started 9 Athletic Advancement 10 Where to Find More Information 11 Membership Categories 11 Code of Conduct 12 Athlete Safety 14 Parents 15 Insurance Coverage 16 Chapter 2: Points and Rankings 19 Event Scoring 20 Freestyle and Freeskiing Points List Calculations 23 Chapter 3: Competition 27 Age Class Competition 28 Junior Nationals 28 FIS Junior World Championships 30 U.S. -

THE DETERMINANTS of SKI RESORT SUCCESS the Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business

THE DETERMINANTS OF SKI RESORT SUCCESS A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Ezekiel Anouna May/2010 THE DETERMINANTS OF SKI RESORT SUCCESS Ezekiel Anouna May, 2010 Economics Abstract As the economy is in a decline, fewer people are willing to pay for luxuries such as vacations. Thus, the ski resort industry is suffering. This thesis reveals an opportunity m the growth of free skiing and a demand for more difficult terrain. In this paper, data is collected from nearly all Colorado ski resorts to form a regression model explaining resort success. Regression analysis is conducted to discover what aspects of a ski resort contribute to success. Primarily, skier visits from the 2008-2009 ski season are_useclas the dependant variable in the regression model to measure resort success. Additionally, hedonic pricing theory is applied to test lift ticket price as a dependant variable. The paper finds that resort size, and possibly terrain park features are related to resort success. The hedonic pricing regression finds that bowl skiing, and lack of crowds, increase consumer willingness to pay for expensive lift tickets. KEYWORDS: (ski resort, terrain park, hedonic pricing) ON MY HONOR, I HAVE NEITHER GIVEN NOR RECEIVED UNAUTHORIZED AID ON THIS THESIS Signature I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Esther Redmount, for her support and consistent efforts to make sure I was on track. I would like to thank my family for supporting me in so many ways throughout my college career. -

Oregon Tourism Commission

Oregon Tourism Commission Staff Report | April 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Optimize Statewide Economic Impact............................................................................... 2 Drive business from key global markets through integrated sales/marketing plans leveraged with global partners and domestic travel trade ..................................................... 2 Facilitate the development of world-class tourism product in partnership with community leaders, tourism businesses and key agencies .................................................... 7 Guide tourism in a way that achieves the optimal balance of visitation, economic impact, natural resources conservation and livability ....................................................................... 10 Inspire overnight leisure travel through industry-leading branding, marketing and communications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Support and Empower Oregon’s Tourism Industry ...................................................... 39 Provide development and training opportunities to meet the evolving tourism industry needs ......................................................................................................................................... 39 Implement industry leading visitor information network ................................................... 46 Fully realize statewide, strategic integration of OTIS (Oregon Tourism Information System) ................................................................................................................................... -

Winter Press Kit 2019-2020

WINTER PRESS KIT 2019-2020 PRESS CONTACT TAYLOR PRATHER [email protected] 970-968-2318 EXT. 38849 OVERVIEW Located 75 miles west of Denver, Colo. in the heart of the Rocky Mountains, Copper Mountain Resort is the preferred mountain destination with an adventurous vibe that represents the best of Colorado. MORE THAN JUST A SKI RESORT, COPPER MOUNTAIN Three pedestrian village areas provide a vibrant atmosphere with lodging, retail, restaurants, bars and TAKES CENTER STAGE AS family activities. On the mountain, Copper’s naturally- THE ULTIMATE VENUE FOR divided terrain offers world-class skiing and riding for ELITE LEVEL TRAINING AND all, including elite level training and competition. COMPETITION IN COLORADO - GIVING GUESTS THE Copper Mountain Resort boasts curated events year- OPPORTUNITY TO SKI AND round and is home to Woodward Copper – a lifestyle RIDE ALONGSIDE WORLD- and action sports hub which includes high-grade on- CLASS ATHLETES. snow training venues and a 19,400 sq. ft. indoor facility. Copper Mountain is part of the POWDR Adventure Lifestyle Co. portfolio. BY THE C o p p e r M o u n t a i n i s c o n v e n i e n t l y l o c a t e d o f f o f I - 7 0 a t E x i t 1 9 5 . t h e r e s o r t i s NUMBERS a p p r o x i m a t e l y 1 0 0 m i l e s ( 2 h o u r s ) f r o m D e n v e r I n t e r n a t i o n a l A i r p o r t a n d 5 5 m i l e s ( 1 h o u r ) f r o m E a g l e C o u n t y R e g i o n a l A i r p o r t .