The Lack of Public Concern for the Increasing Sensationalism In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

The New Woman Criminal in British Culture at the Fin De Siècle

FRAMED DIGITALCULTUREBOOKS is a collaborative imprint of the University of Michigan Press and the University of Michigan Library. FRAMED The New Woman Criminal in British Culture at the Fin de Siècle ELIZABETH CAROLYN MILLER The University of Michigan Press AND The University of Michigan Library ANN ARBOR Copyright © 2008 by Elizabeth Carolyn Miller All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press and the University of Michigan Library Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2011 2010 2009 2008 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Miller, Elizabeth Carolyn, 1974– Framed : the new woman criminal in British culture at the fin de siècle / Elizabeth Carolyn Miller. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-472-07044-2 (acid-free paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-07044-4 (acid-free paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-472-05044-4 (pbk. : acid-free paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-05044-3 (pbk. : acid-free paper) 1. Detective and mystery stories, English—History and criticism. 2. English fiction—19th century—History and criticism. 3. Female offenders in literature. 4. Terrorism in literature. 5. Consumption (Economics) in literature. 6. Feminism and literature— Great Britain—History—19th century. 7. Literature and society— Great Britain—History—19th century. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Invisible Woman

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2009 Invisible Woman Kristin Deanne Howe The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Howe, Kristin Deanne, "Invisible Woman" (2009). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 599. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/599 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVISIBLE WOMAN By KRISTIN DEANNE HOWE Bachelor of Arts, Southwest Minnesota State University, Marshall, Minnesota, 2005 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Philosophy The University of Montana Missoula, MT December 2009 Approved by: Perry Brown, Associate Provost for Graduate Education Graduate School Deborah Slicer, Chairperson Philosophy Christopher Preston Philosophy Elizabeth Hubble Women and Gender Studies ii Howe, Kristin, M.A. December 2009 Philosophy Invisible Women Chairperson: Deborah Slicer Abstract: The aim of this paper is to illuminate the ways in which working class women are invisible within the feminist and ecofeminist movements. Using the faces and forces of oppression as presented by Iris Marion Young and Hilde Lindemann, I show how the working class experiences oppression. I also show how oppression based on class differs from that based on gender and how these differences contribute to the invisibility of working class women within feminism. -

Handbook of Iron Meteorites, Volume 2 (Canyon Diablo, Part 2)

Canyon Diablo 395 The primary structure is as before. However, the kamacite has been briefly reheated above 600° C and has recrystallized throughout the sample. The new grains are unequilibrated, serrated and have hardnesses of 145-210. The previous Neumann bands are still plainly visible , and so are the old subboundaries because the original precipitates delineate their locations. The schreibersite and cohenite crystals are still monocrystalline, and there are no reaction rims around them. The troilite is micromelted , usually to a somewhat larger extent than is present in I-III. Severe shear zones, 100-200 J1 wide , cross the entire specimens. They are wavy, fan out, coalesce again , and may displace taenite, plessite and minerals several millimeters. The present exterior surfaces of the slugs and wedge-shaped masses have no doubt been produced in a similar fashion by shear-rupture and have later become corroded. Figure 469. Canyon Diablo (Copenhagen no. 18463). Shock The taenite rims and lamellae are dirty-brownish, with annealed stage VI . Typical matte structure, with some co henite crystals to the right. Etched. Scale bar 2 mm. low hardnesses, 160-200, due to annealing. In crossed Nicols the taenite displays an unusual sheen from many small crystals, each 5-10 J1 across. This kind of material is believed to represent shock annealed fragments of the impacting main body. Since the fragments have not had a very long flight through the atmosphere, well developed fusion crusts and heat-affected rim zones are not expected to be present. The energy responsible for bulk reheating of the small masses to about 600° C is believed to have come from the conversion of kinetic to heat energy during the impact and fragmentation. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Graphic No Vels & Comics

GRAPHIC NOVELS & COMICS SPRING 2020 TITLE Description FRONT COVER X-Men, Vol. 1 The X-Men find themselves in a whole new world of possibility…and things have never been better! Mastermind Jonathan Hickman and superstar artist Leinil Francis Yu reveal the saga of Cyclops and his hand-picked squad of mutant powerhouses. Collects #1-6. 9781302919818 | $17.99 PB Marvel Fallen Angels, Vol. 1 Psylocke finds herself in the new world of Mutantkind, unsure of her place in it. But when a face from her past returns only to be killed, she seeks vengeance. Collects Fallen Angels (2019) #1-6. 9781302919900 | $17.99 PB Marvel Wolverine: The Daughter of Wolverine Wolverine stars in a story that stretches across the decades beginning in the 1940s. Who is the young woman he’s fated to meet over and over again? Collects material from Marvel Comics Presents (2019) #1-9. 9781302918361 | $15.99 PB Marvel 4 Graphic Novels & Comics X-Force, Vol. 1 X-Force is the CIA of the mutant world—half intelligence branch, half special ops. In a perfect world, there would be no need for an X-Force. We’re not there…yet. Collects #1-6. 9781302919887 | $17.99 PB Marvel New Mutants, Vol. 1 The classic New Mutants (Sunspot, Wolfsbane, Mirage, Karma, Magik, and Cypher) join a few new friends (Chamber, Mondo) to seek out their missing member and go on a mission alongside the Starjammers! Collects #1-6. 9781302919924 | $17.99 PB Marvel Excalibur, Vol. 1 It’s a new era for mutantkind as a new Captain Britain holds the amulet, fighting for her Kingdom of Avalon with her Excalibur at her side—Rogue, Gambit, Rictor, Jubilee…and Apocalypse. -

LOCAS: the MAGGIE and HOPEY STORIES by Jaime Hernandez Study Guide Written by Art Baxter

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators STUDY GUIDE: LOCAS: THE MAGGIE AND HOPEY STORIES by Jaime Hernandez Study guide written by Art Baxter Introduction Comic books were in the midst of change by the early 1980s. The Marvel, DC and Archie lines were going through the same tired motions being produced by second and third generation artists and writers who grew up reading the same books they were now creating. Comic book specialty shops were growing in number and a new "non- returnable" distribution system had been created to supply them. This opened the door for publishers who had small print runs, with color covers and black and white interiors, to emerge with an alternative to corporate mainstream comics. These new comics were often a cross between the familiar genres of the mainstream and the personal artistic freedom of underground comics, but sometimes something altogether different would appear. In 1976, Harvey Pekar began self-publishing his annual autobiographical comics collection, American Splendor, with art by R. Crumb and others, from his home in Cleveland, Ohio. Other cartoonists self-published their mainstream- rejected comics, like Cerebus (Dave Sim, 1977) and Elfquest (Wendy & Richard Pini, 1978) to financial and critical success. With proto-graphic novel publisher, Eclipse, mainstream rebels produced explicit versions of their earlier work, such as Sabre (Don McGreggor & Paul Gulacy, 1978) and Stewart the Rat (Steve Gerber & Gene Colan, 1980). Underground comics evolved away from sex and drugs toward maturity in two anthologies, RAW (Art Spiegleman & Francoise Mouly, eds., 1980) and Weirdo (R. Crumb, ed., 1981). Under the Fantagraphics Books imprint, Gary Groth and Kim Thompson began to publish comics which aspired to an artistic quality that lived up to the high standard set forth in the pages of their critical magazine, The Comics Journal. -

SFU Thesis Template Files

Pulp Fictional Folk Devils? The Fulton Bill and the Campaign to Censor “Crime and Horror Comics” in Cold War Canada, 1945-1955 by Joseph Tilley B.A. (Hons., History), Simon Fraser University, 2008 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Joseph Tilley 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2015 Approval Name: Joseph Tilley Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title: Pulp Fictional Folk Devils? The Fulton Bill and the Campaign to Censor “Crime and Horror Comics” in Cold War Canada, 1945-1955 Examining Committee: Chair: Roxanne Panchasi Associate Professor Allen Seager Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Lara Campbell Supervisor Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies John Herd Thompson External Examiner Professor Emeritus Department of History Duke University Date Defended/Approved: December 15, 2015 ii Abstract This thesis examines the history of and the social, political, intellectual, and cross-border influences behind the “Fulton Bill” and the campaign to censor “crime and horror comics” in Canada from roughly 1945 to 1955. Many – though by no means all – Canadians had grown to believe reading comic books was directly linked with a perceived increase in rates of juvenile criminal behaviour. Led primarily by PTA activists and other civic organizations, the campaign was motivated by a desire to protect the nation’s young people from potential corrupting influences that might lead them to delinquency and deviancy and resulted in amendments to the Criminal Code passed by Parliament in 1949. These amendments criminalized so-called “crime comics” and were thanks to a bill introduced and championed by E. -

2015 Annual Report | the GRANITE YMCA BUILD with US a LETTER from OUR PRESIDENT & CEO Dear Members of the Granite YMCA

GROW. THRIVE. TRANSFORM. 2015 Annual Report | THE GRANITE YMCA BUILD WITH US A LETTER FROM OUR PRESIDENT & CEO Dear Members of The Granite YMCA, Two years ago, The Granite YMCA trustees and staff approved a new strategic plan with a vision to build a stronger, healthier and more harmonious community through new programs to be offered at all of our branches. Our belief was that by focusing on developing healthy children of strong character, strengthening families and building leadership around social responsibility, that the YMCA could be a major force in changing the fabric of our community. These were lofty goals but I’m pleased to report that we have done just that and it is exciting to see. As of this report, we are on our third launch of our character development programs for youth having rolled out this initiative in all of our camps, child care programs and aquatics. This has involved over 3,000 youth who are taught, mentored and recognized for displaying outstanding character. They receive awards as “character rock stars” and it is really fantastic to see our children embrace becoming role models of outstanding character. Our staff has been trained in a new program called “Courage to Care,” an anti-bullying curriculum for teens which asks them to step up when bullying occurs and be an advocate of caring, empathy and respect of others. This is part of a major initiative to provide safe and enriching opportunities for teens. We are building two new Centers for Youth and Teen Leadership this year in Manchester and Goffstown as a part of our current $3.1 million dollar capital campaign. -

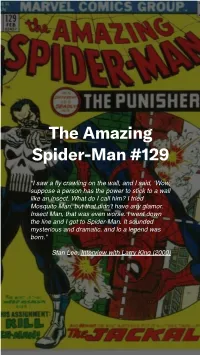

ASM 129 Investment Memo V4

The Amazing Spider-Man #129 “I saw a fly crawling on the wall, and I said, ‘Wow, suppose a person has the power to stick to a wall like an insect. What do I call him? I tried Mosquito Man, but that didn’t have any glamor. Insect Man, that was even worse. I went down the line and I got to Spider-Man. It sounded mysterious and dramatic, and lo a legend was born.” Stan Lee, Interview with Larry King (2000) Background Otis recently acquired a 9.8 CGC Grade “Amazing Spider-Man #129” comic book. This document aims to share the story of this asset. Table Of Contents OTIS OVERVIEW 4 HIGHLIGHTS 5 THE COMIC BOOK INDUSTRY 7 COMIC BOOK AGES 11 THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #129 14 GRADE & CONDITION 17 SUMMARY OF HISTORICAL SALES 18 INVESTMENT RISKS 22 2 What Is Otis Everyone has their thing. Maybe yours is sneakers, or maybe it's contemporary art. Whatever it is, you get it — the value assigned to a certain item, its cultural significance, why it matters. But more often than not, ownership of grails is out of the picture, whether because fewer than 100 were made, or because that six-figure price tag just doesn't work with your budget. At Otis, we turn aficionados into shareholders. We believe in transparency, liquidity, and trusting your own gut. We're democratizing an otherwise closed market and making these alternative assets accessible. Own shares in the things that you value, and whose value you understand and build a portfolio better suited to a museum than a stock ticker. -

Spawn Origins: Volume 20 Free

FREE SPAWN ORIGINS: VOLUME 20 PDF Danny Miki,Angel Medina,Brian Holguin,Todd McFarlane | 160 pages | 04 Mar 2014 | Image Comics | 9781607068624 | English | Fullerton, United States Spawn (comics) - Wikipedia This Spawn series collects the original comics from the beginning in new trade paperback volumes. Launched inthis line of newly redesigned and reformatted trade paperbacks replaces the Spawn Collection line. These new trades feature new cover art by Greg Capullo, recreating classic Spawn covers. In addition to the 6-issue trade paperbacks, thi… More. Book 1. Featuring the stories and artwork by Todd McFarla… More. Want to Read. Shelving menu. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 1. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Rate it:. Book 2. Featuring the stories and artwork by Spawn creator… More. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 2. Book 3. Spawn Origins: Volume 20 Spawn Origins, Volume 3. Book 4. Todd McFarlane's Spawn smashed all existing record… More. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume Spawn Origins: Volume 20. Book 5. Featuring the stories and artwork by Todd Mcfarla… More. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 5. Book 6. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 6. Book 7. Spawn survives torture at the hands of his enemies… More. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 7. Book 8. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 8. Book 9. Journey with Spawn as he visits the Fifth Level of… More. Shelve Spawn Origins, Volume 9. Book Cy-Gor's arduous hunt for Spawn reaches its pinnac… More. Shelve Spawn Spawn Origins: Volume 20, Volume Spawn partners with Terry Fitzgerald as his plans … More. The Freak returns with an agenda of his own and Sa… More.