Chapter 10 Chemical Bonding II: Molecular Shapes, Valence Bond Theory, and Molecular Orbital Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemistry 2000 Slide Set 1: Introduction to the Molecular Orbital Theory

Chemistry 2000 Slide Set 1: Introduction to the molecular orbital theory Marc R. Roussel January 2, 2020 Marc R. Roussel Introduction to molecular orbitals January 2, 2020 1 / 24 Review: quantum mechanics of atoms Review: quantum mechanics of atoms Hydrogenic atoms The hydrogenic atom (one nucleus, one electron) is exactly solvable. The solutions of this problem are called atomic orbitals. The square of the orbital wavefunction gives a probability density for the electron, i.e. the probability per unit volume of finding the electron near a particular point in space. Marc R. Roussel Introduction to molecular orbitals January 2, 2020 2 / 24 Review: quantum mechanics of atoms Review: quantum mechanics of atoms Hydrogenic atoms (continued) Orbital shapes: 1s 2p 3dx2−y 2 3dz2 Marc R. Roussel Introduction to molecular orbitals January 2, 2020 3 / 24 Review: quantum mechanics of atoms Review: quantum mechanics of atoms Multielectron atoms Consider He, the simplest multielectron atom: Electron-electron repulsion makes it impossible to solve for the electronic wavefunctions exactly. A fourth quantum number, ms , which is associated with a new type of angular momentum called spin, enters into the theory. 1 1 For electrons, ms = 2 or − 2 . Pauli exclusion principle: No two electrons can have identical sets of quantum numbers. Consequence: Only two electrons can occupy an orbital. Marc R. Roussel Introduction to molecular orbitals January 2, 2020 4 / 24 The hydrogen molecular ion The quantum mechanics of molecules + H2 is the simplest possible molecule: two nuclei one electron Three-body problem: no exact solutions However, the nuclei are more than 1800 time heavier than the electron, so the electron moves much faster than the nuclei. -

Theoretical Methods That Help Understanding the Structure and Reactivity of Gas Phase Ions

International Journal of Mass Spectrometry 240 (2005) 37–99 Review Theoretical methods that help understanding the structure and reactivity of gas phase ions J.M. Merceroa, J.M. Matxaina, X. Lopeza, D.M. Yorkb, A. Largoc, L.A. Erikssond,e, J.M. Ugaldea,∗ a Kimika Fakultatea, Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, P.K. 1072, 20080 Donostia, Euskadi, Spain b Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota, 207 Pleasant St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455-0431, USA c Departamento de Qu´ımica-F´ısica, Universidad de Valladolid, Prado de la Magdalena, 47005 Valladolid, Spain d Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Box 596, Uppsala University, 751 24 Uppsala, Sweden e Department of Natural Sciences, Orebro¨ University, 701 82 Orebro,¨ Sweden Received 27 May 2004; accepted 14 September 2004 Available online 25 November 2004 Abstract The methods of the quantum electronic structure theory are reviewed and their implementation for the gas phase chemistry emphasized. Ab initio molecular orbital theory, density functional theory, quantum Monte Carlo theory and the methods to calculate the rate of complex chemical reactions in the gas phase are considered. Relativistic effects, other than the spin–orbit coupling effects, have not been considered. Rather than write down the main equations without further comments on how they were obtained, we provide the reader with essentials of the background on which the theory has been developed and the equations derived. We committed ourselves to place equations in their own proper perspective, so that the reader can appreciate more profoundly the subtleties of the theory underlying the equations themselves. Finally, a number of examples that illustrate the application of the theory are presented and discussed. -

Valence Bond Theory

UMass Boston, Chem 103, Spring 2006 CHEM 103 Molecular Geometry and Valence Bond Theory Lecture Notes May 2, 2006 Prof. Sevian Announcements z The final exam is scheduled for Monday, May 15, 8:00- 11:00am It will NOT be in our regularly scheduled lecture hall (S- 1-006). The final exam location has been changed to Snowden Auditorium (W-1-088). © 2006 H. Sevian 1 UMass Boston, Chem 103, Spring 2006 More announcements Information you need for registering for the second semester of general chemistry z If you will take it in the summer: z Look for chem 104 in the summer schedule (includes lecture and lab) z If you will take it in the fall: z Look for chem 116 (lecture) and chem 118 (lab). These courses are co-requisites. z If you plan to re-take chem 103, in the summer it will be listed as chem 103 (lecture + lab). In the fall it will be listed as chem 115 (lecture) + chem 117 (lab), which are co-requisites. z Note: you are only eligible for a lab exemption if you previously passed the course. Agenda z Results of Exam 3 z Molecular geometries observed z How Lewis structure theory predicts them z Valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory z Valence bond theory z Bonds are formed by overlap of atomic orbitals z Before atoms bond, their atomic orbitals can hybridize to prepare for bonding z Molecular geometry arises from hybridization of atomic orbitals z σ and π bonding orbitals © 2006 H. Sevian 2 UMass Boston, Chem 103, Spring 2006 Molecular Geometries Observed Tetrahedral See-saw Square planar Square pyramid Lewis Structure Theory -

Lewis Structure Handout

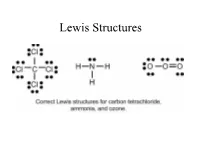

Lewis Structure Handout for Chemistry Students An electron dot diagram, also known as a Lewis Structure, is a representation of valence electrons in a single atom, and can be further utilized to depict the bonds that form based on the available electrons for covalent bonding between multiple atoms. -Each atom has a characteristic dot diagram based on its position in the periodic table and this reflects its potential for fulfillment of the octet rule. As a general rule, the noble gases have a filled octet (column VIII with eight valence electrons) and each preceding column has successively one fewer. • For example, Carbon is in column IV and has four valence electrons. It can therefore be represented as: • Each of these "lone" electrons can form a bond by sharing the orbital with another unbonded electron. Hydrogen, being in column I, has a single valence electron, and will therefore satisfy carbon's octet thusly: • When a compound has bonded electrons (as with CH4) it is most accurate to diagram it with lines representing each of the single bonds. • Using carbon again for a slightly more complicated example, it can also form double bonds. This is the case when carbon bonds to two oxygen atoms, resulting in CO2. The oxygen atoms (with six valence electrons in column VI) are each represented as: • Because carbon is the least electronegative of the atoms involved, it is placed centrally, and its valence electrons will migrate toward the more electronegative oxygens to form two double bonds and a linear structure. This can be written as: where oxygen's remaining lone pairs are still shown. -

Introduction to Molecular Orbital Theory

Chapter 2: Molecular Structure and Bonding Bonding Theories 1. VSEPR Theory 2. Valence Bond theory (with hybridization) 3. Molecular Orbital Theory ( with molecualr orbitals) To date, we have looked at three different theories of molecular boning. They are the VSEPR Theory (with Lewis Dot Structures), the Valence Bond theory (with hybridization) and Molecular Orbital Theory. A good theory should predict physical and chemical properties of the molecule such as shape, bond energy, bond length, and bond angles.Because arguments based on atomic orbitals focus on the bonds formed between valence electrons on an atom, they are often said to involve a valence-bond theory. The valence-bond model can't adequately explain the fact that some molecules contains two equivalent bonds with a bond order between that of a single bond and a double bond. The best it can do is suggest that these molecules are mixtures, or hybrids, of the two Lewis structures that can be written for these molecules. This problem, and many others, can be overcome by using a more sophisticated model of bonding based on molecular orbitals. Molecular orbital theory is more powerful than valence-bond theory because the orbitals reflect the geometry of the molecule to which they are applied. But this power carries a significant cost in terms of the ease with which the model can be visualized. One model does not describe all the properties of molecular bonds. Each model desribes a set of properties better than the others. The final test for any theory is experimental data. Introduction to Molecular Orbital Theory The Molecular Orbital Theory does a good job of predicting elctronic spectra and paramagnetism, when VSEPR and the V-B Theories don't. -

8.3 Bonding Theories >

8.3 Bonding Theories > Chapter 8 Covalent Bonding 8.1 Molecular Compounds 8.2 The Nature of Covalent Bonding 8.3 Bonding Theories 8.4 Polar Bonds and Molecules 1 Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved. 8.3 Bonding Theories > Molecular Orbitals Molecular Orbitals How are atomic and molecular orbitals related? 2 Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved. 8.3 Bonding Theories > Molecular Orbitals • The model you have been using for covalent bonding assumes the orbitals are those of the individual atoms. • There is a quantum mechanical model of bonding, however, that describes the electrons in molecules using orbitals that exist only for groupings of atoms. 3 Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved. 8.3 Bonding Theories > Molecular Orbitals • When two atoms combine, this model assumes that their atomic orbitals overlap to produce molecular orbitals, or orbitals that apply to the entire molecule. 4 Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved. 8.3 Bonding Theories > Molecular Orbitals Just as an atomic orbital belongs to a particular atom, a molecular orbital belongs to a molecule as a whole. • A molecular orbital that can be occupied by two electrons of a covalent bond is called a bonding orbital. 5 Copyright © Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliates. All Rights Reserved. 8.3 Bonding Theories > Molecular Orbitals Sigma Bonds When two atomic orbitals combine to form a molecular orbital that is symmetrical around the axis connecting two atomic nuclei, a sigma bond is formed. • Its symbol is the Greek letter sigma (σ). -

Lewis Structures

Lewis Structures Valence electrons for Elements Recall that the valence electrons for the elements can be determined based on the elements position on the periodic table. Lewis Dot Symbol Valence electrons and number of bonds Number of bonds elements prefers depending on the number of valence electrons. In general - F a m i l y → # C o v a l e n t B o n d s* H a l o g e n s X F , B r , C l , I → 1 bond often C a l c o g e n s O 2 bond often O , S → N i t r o g e n N 3 bond often N , P → C a r b o n C → 4 bond always C , S i The above chart is a guide on the number of bonds formed by these atoms. Lewis Structure, Octet Rule Guidelines When compounds are formed they tend to follow the Octet Rule. Octet Rule: Atoms will share electrons (e-) until it is surrounded by eight valence electrons. 4 unpaired 3unpaired 2unpaired 1unpaired up = unpaired e- 4 bonds 3 bonds 2 bonds 1 bond O=C=O N≡ N O = O F - F Atomic Connectivity The atomic arrangement for a molecule is usually given. CH2ClF HNO3 CH3COOH H2SO4 Cl N H O O O O H C F O H C C H O S O H H H H O H O In general when there is a single central atom in the 3- molecule, CH2ClF, SeCl2, O3 (CO2, NH3, PO4 ), the central atom is the first atom in the chemical formula. -

Draw Three Resonance Structures for the Chlorate Ion, Clo3

University Chemistry Quiz 3 2014/11/6 + 1. (10%) Explain why the bond order of N2 is greater than that of N2 , but the bond + order of O2 is less than that of O2 . Sol. + In forming the N2 from N2, an electron is removed from the sigma bonding molecular orbital. Consequently, the bond order decreases to 2.5 from 3.0. In + forming the O2 ion from O2, an electron is removed from the pi antibonding molecular orbital. Consequently, the bond order increases to 2.5 from 2.0. - 2. (10%) Draw three resonance structures for the chlorate ion, ClO3 . Show formal charges. Sol. Strategy: We follow the procedure for drawing Lewis structures outlined in Section 3.4 of the text. After we complete the Lewis structure, we draw the resonance structures. Solution: Following the procedure in Section 3.4 of the text, we come up with − the following Lewis structure for ClO3 . O − + − O Cl O We can draw two more equivalent Lewis structures with the double bond between Cl and a different oxygen atom. The resonance structures with formal charges are as follows: − − O O O + − − + − − + O Cl O O Cl O O Cl O 3. (5%) Use the molecular orbital energy-level diagram for O2 to show that the following Lewis structure corresponds to an excited state: Sol. The Lewis structure shows 4 pairs of electrons on the two oxygen atoms. From Table 3.4 of the text, we see that these 8 valence electrons are placed in the σ p p p p 2p , 2p , 2p , 2p , and 2p orbitals. -

Molecular Orbital Theory

Molecular Orbital Theory The Lewis Structure approach provides an extremely simple method for determining the electronic structure of many molecules. It is a bit simplistic, however, and does have trouble predicting structures for a few molecules. Nevertheless, it gives a reasonable structure for many molecules and its simplicity to use makes it a very useful tool for chemists. A more general, but slightly more complicated approach is the Molecular Orbital Theory. This theory builds on the electron wave functions of Quantum Mechanics to describe chemical bonding. To understand MO Theory let's first review constructive and destructive interference of standing waves starting with the full constructive and destructive interference that occurs when standing waves overlap completely. When standing waves only partially overlap we get partial constructive and destructive interference. To see how we use these concepts in Molecular Orbital Theory, let's start with H2, the simplest of all molecules. The 1s orbitals of the H-atom are standing waves of the electron wavefunction. In Molecular Orbital Theory we view the bonding of the two H-atoms as partial constructive interference between standing wavefunctions of the 1s orbitals. The energy of the H2 molecule with the two electrons in the bonding orbital is lower by 435 kJ/mole than the combined energy of the two separate H-atoms. On the other hand, the energy of the H2 molecule with two electrons in the antibonding orbital is higher than two separate H-atoms. To show the relative energies we use diagrams like this: In the H2 molecule, the bonding and anti-bonding orbitals are called sigma orbitals (σ). -

Covalent Bonding and Molecular Orbitals

Covalent Bonding and Molecular Orbitals Chemistry 35 Fall 2000 From Atoms to Molecules: The Covalent Bond n So, what happens to e- in atomic orbitals when two atoms approach and form a covalent bond? Mathematically: -let’s look at the formation of a hydrogen molecule: -we start with: 1 e-/each in 1s atomic orbitals -we’ll end up with: 2 e- in molecular obital(s) HOW? Make linear combinations of the 1s orbital wavefunctions: ymol = y1s(A) ± y1s(B) Then, solve via the SWE! 2 1 Hydrogen Wavefunctions wavefunctions probability densities 3 Hydrogen Molecular Orbitals anti-bonding bonding 4 2 Hydrogen MO Formation: Internuclear Separation n SWE solved with nuclei at a specific separation distance . How does the energy of the new MO vary with internuclear separation? movie 5 MO Theory: Homonuclear Diatomic Molecules n Let’s look at the s-bonding properties of some homonuclear diatomic molecules: Bond order = ½(bonding e- - anti-bonding e-) For H2: B.O. = 1 - 0 = 1 (single bond) For He2: B.O. = 1 - 1 = 0 (no bond) 6 3 Configurations and Bond Orders: 1st Period Diatomics Species Config. B.O. Energy Length + 1 H2 (s1s) ½ 255 kJ/mol 1.06 Å 2 H2 (s1s) 1 431 kJ/mol 0.74 Å + 2 * 1 He2 (s1s) (s 1s) ½ 251 kJ/mol 1.08 Å 2 * 2 He2 (s1s) (s 1s) 0 ~0 LARGE 7 Combining p-orbitals: s and p MO’s antibonding end-on overlap bonding antibonding side-on overlap bonding antibonding bonding8 4 2nd Period MO Energies s2p has lowest energy due to better overlap (end-on) of 2pz orbitals p2p orbitals are degenerate and at higher energy than the s2p 9 2nd Period MO Energies: Shift! For Z <8: 2s and 2p orbitals can interact enough to change energies of the resulting s2s and s2p MOs. -

3-MO Theory(U).Pptx

Molecular Orbital Theory Valence Bond Theory: Electrons are located in discrete pairs between specific atoms Molecular Orbital Theory: Electrons are located in the molecule, not held in discrete regions between two bonded atoms Thus the main difference between these theories is where the electrons are located, in valence bond theory we predict the electrons are always held between two bonded atoms and in molecular orbital theory the electrons are merely held “somewhere” in molecule Mathematically can represent molecule by a linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) ΨMOL = c1 φ1 + c2 φ2 + c3 φ3 + cn φn Where Ψ2 = spatial distribution of electrons If the ΨMOL can be determined, then where the electrons are located can also be determined 66 Building Molecular Orbitals from Atomic Orbitals Similar to a wave function that can describe the regions of space where electrons reside on time average for an atom, when two (or more) atoms react to form new bonds, the region where the electrons reside in the new molecule are described by a new wave function This new wave function describes molecular orbitals instead of atomic orbitals Mathematically, these new molecular orbitals are simply a combination of the atomic wave functions (e.g LCAO) Hydrogen 1s H-H bonding atomic orbital molecular orbital 67 Building Molecular Orbitals from Atomic Orbitals An important consideration, however, is that the number of wave functions (molecular orbitals) resulting from the mixing process must equal the number of wave functions (atomic orbitals) used in the mixing -

Simple Molecular Orbital Theory Chapter 5

Simple Molecular Orbital Theory Chapter 5 Wednesday, October 7, 2015 Using Symmetry: Molecular Orbitals One approach to understanding the electronic structure of molecules is called Molecular Orbital Theory. • MO theory assumes that the valence electrons of the atoms within a molecule become the valence electrons of the entire molecule. • Molecular orbitals are constructed by taking linear combinations of the valence orbitals of atoms within the molecule. For example, consider H2: 1s + 1s + • Symmetry will allow us to treat more complex molecules by helping us to determine which AOs combine to make MOs LCAO MO Theory MO Math for Diatomic Molecules 1 2 A ------ B Each MO may be written as an LCAO: cc11 2 2 Since the probability density is given by the square of the wavefunction: probability of finding the ditto atom B overlap term, important electron close to atom A between the atoms MO Math for Diatomic Molecules 1 1 S The individual AOs are normalized: 100% probability of finding electron somewhere for each free atom MO Math for Homonuclear Diatomic Molecules For two identical AOs on identical atoms, the electrons are equally shared, so: 22 cc11 2 2 cc12 In other words: cc12 So we have two MOs from the two AOs: c ,1() 1 2 c ,1() 1 2 2 2 After normalization (setting d 1 and _ d 1 ): 1 1 () () [2(1 S )]1/2 12 [2(1 S )]1/2 12 where S is the overlap integral: 01 S LCAO MO Energy Diagram for H2 H2 molecule: two 1s atomic orbitals combine to make one bonding and one antibonding molecular orbital.