Mondayvol3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

In the Break: the Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition

In the Break This page intentionally left blank In the Break The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition Fred Moten University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis • London Copyright 2003 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota Portions of chapter 1 were originally published as “Voices/Forces: Migration, Surplus, and the Black Avant-Garde,” in Writing Aloud: The Sonics of Language, edited by Brandon LaBelle and Christof Migone (Los Angeles: Errant Bodies Press, 2001); reprinted by permission of Errant Bodies Press. Portions of chapter 1 also appeared as “Sound in Florescence: Cecil Taylor Floating Garden,” in Sound States: Innovative Poetics and Acoustical Technologies, edited by Adalaide Morris (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998); copyright 1998 by the University of North Carolina Press; reprinted by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. An earlier version of chapter 2 appeared as “From Ensemble to Improvisation,” in Hambone 16 (Fall 2002); reprinted by permission of Hambone. An earlier version of chapter 3 appeared as “Black Mo’nin’ in the Sound of the Photograph,” in Loss, edited by David Kazanjian and David Eng (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002); copyright 2002 by the Regents of the University of California; reprinted by permission of the University of California Press. Translated poetry by Antonin Artaud in chapter 1 originally appeared in WatchWends and Rack Screams: Works from the Final Period, edited and translated by Clayton Eshleman and Bernard Bador (Boston: Exact Change, 1995); reprinted courtesy of Exact Change. Lush Life, by Billy Strayhorn, copyright 1949 (renewed) by Music Sales Corporation (ASCAP) and Tempo Music Corporation (BMI); all rights administered by Music Sales Corporation (ASCAP); international copyright secured; all rights reserved; reprinted by permission. -

Occasions of Cecil Taylor's Poetry

American Music Review The H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York Volume XLIX, Issue 1 Fall 2019 “The Scented Parabola”: Occasions of Cecil Taylor’s Poetry David Grubbs It was, in retrospect, an especially inapt introduction. On the occasion in the spring of 2012 of Brooklyn College awarding Cecil Taylor, longtime resident of the borough of Brooklyn, an honorary doctorate of Fine Arts, Taylor’s contributions—introduced with the caveat “Some contend . .”— were described exclusively in terms of the development of jazz, and with various incongruities, including John Coltrane inexplicably referred to in the introduction as “Johnny.” As Taylor approached the microphone, one might have anticipated his remarks to center on a lifetime in music. And, in a way, they did. After a brief greeting, Taylor began: it leans within the scented parabola of a grey slated rising palm of dampened mud impossible to discern the trigonal or endomorphism set and the architectural grid [ . ]1 Seated among the faculty close to the dais, and thus with my back to the thousands of attendees on the quad at Brooklyn College on a late May morning so perfect that I still recall the sunburn on the top of my head, I turned around and saw several thousand mouths to varying degrees agape at the spectacle of this unexpected performance. It seems impossible to overstate how unprepared the crowd was to receive Cecil Taylor’s delivery of his poetry, and I imagine that I will never again see an audience of that size so mystified—but also concerned. -

Jazz Poetry Bibliography.Pdf

A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF JAZZ POETRY CRITICISM by Brent Hayes Edwards and John F. Szwed This bibliography has been updated and expanded from its original publication in Callaloo: A Journal of African Diaspora Arts and Letters Callaloo 25.1 (Winter 2002): 338-346. Books, Dissertations and Anthologies Algarin, Miguel and Bob Holman, eds. Aloud: Voices From the Nuyorican Poets Cafe. New York: Henry Holt, 1994. Anderson, T.J. III. Notes to Make the Sound Come Right: Four Innovators of Jazz Poetry. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2004. Baraka, Amiri and Amina Baraka. The Music: Reflections on Jazz and Blues. New York: Morrow, 1987. Benston, Kimberly W. Performing Blackness: Enactments of African-American Modernism. London: Routledge, 2000. Bonner, Patricia Elaine. “Sassy Jazz and Slo’ Draggin’ Blues as Sung by Langston Hughes.” Diss. University of South Florida, 1990. Borshuk, Michael Thomas. “Swinging the Vernacular: Jazz and African American Modernist Literature.” Ph.D Dissertation, University of Alberta, 2002. Brown, Fahamisha. Performing the Word: African-American Poetry as Vernacular Culture. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1999. Brown, Patrick James. “Jazz Poetry: Definition, Analysis, and Performance.” Diss. University of Southern California, 1978. Buchwald, Emilie and Ruth Roston, eds. Mixed Voices: Contemporary Poems about Music. Minneapolis: Milkweed, 1991. Cerulli, Dom, Burt Korall, and Mort L. Nasatir, eds. The Jazz Word. New York: Ballantine, 1960. Charters, Samuel. The Poetry of the Blues. New York: Oak Publications, 1963. Chinitz, David. “Jazz and Jazz Discourse in Modernist Poetry: T. S. Eliot and Langston Hughes.” Diss. Columbia University, 1993. Feinstein, Sascha. Jazz Poetry: From the 1920s to the Present. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1997. -

Print/Download Entire Issue (PDF)

American Music Review The H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York Volume XLIX, Issue 1 Fall 2019 “The Scented Parabola”: Occasions of Cecil Taylor’s Poetry David Grubbs It was, in retrospect, an especially inapt introduction. On the occasion in the spring of 2012 of Brooklyn College awarding Cecil Taylor, longtime resident of the borough of Brooklyn, an honorary doctorate of Fine Arts, Taylor’s contributions—introduced with the caveat “Some contend . .”—were described exclusively in terms of the development of jazz, and with various incongruities, including John Coltrane inexplicably referred to in the introduction as “Johnny.” As Taylor approached the microphone, one might have anticipated his remarks to center on a lifetime in music. And, in a way, they did. After a brief greeting, Taylor began: it leans within the scented parabola of a grey slated rising palm of dampened mud impossible to discern the trigonal or endomorphism set and the architectural grid [ . ]1 Seated among the faculty close to the dais, and thus with my back to the thousands of attendees on the quad at Brooklyn College on a late May morning so perfect that I still recall the sunburn on the top of my head, I turned around and saw several thousand mouths to varying degrees agape at the spectacle of this unexpected performance. It seems impossible to overstate how unprepared the Inside This Issue crowd was to receive Cecil Taylor’s Institute News by Stephanie Jensen-Moulton...........................................................5 delivery of his poetry, and I imagine that I will never again see an Sonic Arts for All! by Max Alper..........................................................................7 audience of that size so mystified— Helena Brown on the Met’s Porgy and Bess..............................................................11 but also concerned. -

Teemu Mäki. List of Albums in My CD Collection, 28.8.2021

Sivu 1 / 261 Musiikki 65078 kappaletta, 257,5 päivää, 2,14 Tt Artisti Albumi Kappalemäärä Kesto A-Trak Vs. DJ Q-Bert Buck Tooth Wizards (1997, A-Trak Vs. DJ Q-Bert) 1 1:02:17 Aapo Häkkinen William Byrd: Music For The Virginals (rec.1999, Aapo Häkkinen) 15 1:10:51 Aaron Parks Invisible Cinema (20.–22.1.2008, Aaron Parks & Mike Moreno, Matt Penma… 10 55:01 Abbey Lincoln Abbey Lincoln Sings Billie Holiday, Vol. 1 (6.–7.11.1987) 10 57:07 Abbey Lincoln Abbey Lincoln Sings Billie Holiday, Vol. 2 (6.–7.11.1987) 7 40:19 Abbey Lincoln Abbey Sings Abbey (Lincoln, 25.–27.9 & 17.11.2006) 12 59:43 Abbey Lincoln Devil's Got Your Tongue (24.–25.2.1992, Abbey Lincoln) 11 1:10:00 Abbey Lincoln It's Magic (8/1958, Abbey Lincoln) 10 37:09 Abbey Lincoln It's Me (2002—2003, Abbey Lincoln) 11 52:49 Abbey Lincoln Over The Years (18.–21.2.2000, Abbey Lincoln) 10 51:03 Abbey Lincoln Painted Lady (30.5.1987, Abbey Lincoln feat. Archie Shepp) 6 44:49 Abbey Lincoln Talking To The Sun (25.–26.11.1983, Abbey Lincoln & S.Coleman/J.Weidm… 5 30:14 Abbey Lincoln A Turtle's Dream (May-Nov.1994, Abbey Lincoln) 11 1:09:10 Abbey Lincoln Who Used To Dance (5.–7.4. & 19.5.1996, Abbey Lincoln) 9 1:01:29 Abbey Lincoln Wholly Earth (3.–5.6.1998, Abbey Lincoln) 10 1:07:32 Abbey Lincoln The World Is Falling Down (21.–27.2.1990, Abbey Lincoln & C.Terry/J.McLe… 8 49:23 Abbey Lincoln You Gotta Pay the Band (2/1991, Abbey Lincoln & S.Getz/H.Jones/C.Hade… 10 58:31 Abbey Lincoln & Hank Jones When There Is Love (4.–6.10.1992, Abbey Lincoln & Hank Jones) 14 1:03:58 Abdullah Ibrahim Abdullah -

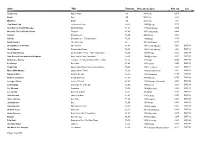

Artis Title Format Released Label Ref. No. Loc. Page 1 Of

Artis Title Format Released Label Ref. no. Loc. Seaworthy Map in Hand CD 2007 12k 6273 Pjusk Sart CD 2007 12k 6272 Moskitoo Drape CD 2007 12k 6271 Cop Shoot Cop Consumer Revolt FLAC 1992 Big Cat 6270 Shankar Lal & Sunil Banerjee Morning Raga FLAC 1996 Bandaloop 6269 Riccardo Tesi & Banda Italiana Thapsos FLAC 2000 Il Manifesto 6268 Various Ethiopiques 3 FLAC 2000 Buda 6267 Various Ethiopiques 5 - Tigrigna Music FLAC 1999 Buda 6266 Noah Howard The Black Ark LP 2007 Bo'Weavil 6265 Shelly Manne & His Men The Gambit FLAC 1958 Contemporary 6264 DVD164 Shelly Manne Steps to the Desert FLAC 1962 Contemporary 6263 DVD164 Serge Gainsbourg La Javanaise ( Vol.2 - 1961-1962-1963) FLAC 1989 Philips 6262 DVD164 Sam Rivers & the Andrew Hill Quartet Rare Tracks From "Involution" FLAC 1966 Blue Note 6261 DVD163 Robert Lee Mccoy Complete Recorded Works (1937 - 1940) FLAC 1998 Wolf 6260 DVD163 PJ Harvey Rid of Me FLAC 1993 Island 6259 DVD163 Oskar Sala Oskar Sala: Elektronische Impressionen FLAC 1978 Telefunken 6258 DVD163 Nurse With Wound Ladies Home Tickler FLAC 1980 United Dairies 6257 DVD163 Mulgrew Miller Keys to the City FLAC 1985 Landmark 6256 DVD163 Médéric Collignon Porgy And Bess FLAC 2006 Minium 6255 DVD163 Lounge Lizards Voice of Chunk FLAC 1989 Strange & Beautiful 6254 DVD163 Li Xiangting China the Art of the Qin FLAC 1990 Ocora 6253 DVD163 Lee Morgan Caramba FLAC 1968 Blue Note 6252 DVD163 Lee Konitz Some New Stuff FLAC 2000 DIW 6251 DVD163 Julie London Twin Best Now FLAC 1992 Liberty 6250 DVD163 John Coltrane Sun Ship FLAC 1965 Impulse! 6249 DVD163 Jan Garbarek Dis FLAC 1977 ECM 6248 DVD163 Jan Garbarek The Esoteric Circle FLAC 1969 Freedom 6247 DVD163 Ibrahim Ferrer Mi Sueño FLAC 2007 World Circuit 6246 DVD162 Gene Ammons Boss Tenor (RVG Remaster) FLAC 1960 Blue Note 6245 DVD162 Flanger Nuclear Jazz FLAC 2007 Nonplace 6244 DVD162 Fela Kuti Expensive Shit + He Miss Road FLAC 1975 Universal 6243 DVD162 Ali Akbar Khan Journey FLAC 1990 Triloka 6242 DVD162 Xiu Xiu vs. -

Artis Title Format Released Label Ref. No. Loc. Page 1 Of

Artis Title Format Released Label Ref. no. Loc. !!! Me and Giuliani Down by the Schoolyard (a True Story) CD-R 2003 Touch & Go 3690 !!! Louden Up Now FLAC 2004 Touch & Go 5637 DVD123 !!! Take Ecstasy With Me - Get Up FLAC 2005 Touch & Go 5161 DVD090 :zoviet-france: Just an Illusion FLAC 1990 Staalplaat 5073 DVD078 µ-Ziq Tango N' Vectif CD-R 1993 Rephlex 1151 µ-Ziq Mu-Ziq Vs The Auteurs CD-R 1994 Hut 2713 µ-Ziq Bluff Limbo 2CD-R 1994 Rephlex 3410 µ-Ziq In Pine Effect FLAC 31/10/1995 Astralwerks 4334 DVD028 µ-Ziq Lunatic Harness CD 1997 Astralwerks 4308 µ-Ziq Lunatic Harness CD-R 1997 Astralwerks 1251 µ-Ziq Urmur Bile Trax CD-R 1997 Astralwerks 1935 µ-Ziq Royal Astronomy CD-R 1999 Hut 1620 The 13th Floor Elevators The Psychedelic Sounds Of... CD-R 1978 Radarscope 1694 The 13th Floor Elevators Easter Everywhere CD-R 1996 Charly 1922 The 13th Floor Elevators The Psychedelic World Of The 13th Floor Elevators 3CD-R 2002 Charly 3317 13th Tribe Ping-Pong Anthropology CD-R 1992 Review 0938 16 Horsepower Secret South CD-R 2000 Razor & Tie 3653 16 Horsepower Folklore CD-R 2002 Jetset 1049 16B Sounds From Another Room CD-R 1998 Eye Q 2175 La 1919 Giorni Felici CD-R Materiali Sonori 1707 1-Speed Bike Droopy Butt Begone! CD-R 2000 Constellation 2693 24 Grana Loop CD-R 1997 La Canzonetta 2240 3/4HadBeenEliminated 3QuartersHadBeenEliminated CD 2003 Bowindo 4950 3/4HadBeenEliminated A Year of the Aural Gauge Operation FLAC 2006 Häpna 4993 DVD072 3/4HadBeenEliminated DimethylAtonalCalcine 7" 2006 Shifting Position 4954 33.3 33.3 CD-R 1999 Aesthetics 1723 33.3 Plays Music CD-R 2000 Aesthetics 1723 4E Introducing DJ Snax 4e4me4you CD Mille Plateaux 3905 4Hero Two Pages CD-R 1998 Reinforced 1297 4Hero Creating Patterns CD-R 2001 Talkin' Loud 0740 69 (Carl Craig) The Sound Of Music CD-R R&S 2316 808 State Newbuild CD-R Rephlex 3264 90 Day Men (It (Is) It) Critical Band CD Southern 0269 Page 1 of 203 Artis Title Format Released Label Ref.