Story, History and Intercultural Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Money Laundering Cases Involving Russian Individuals and Their Effect on the Eu”

29-01-2019 1 SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL CRIMES, TAX EVASION AND TAX AVOIDANCE (TAX3) TUESDAY 29 JANUARY 2019 * * * PUBLIC HEARING “MONEY LAUNDERING CASES INVOLVING RUSSIAN INDIVIDUALS AND THEIR EFFECT ON THE EU” * * * Panel I: Effects in the EU of the money laundering cases involving Russian linkages Anders Åslund, Senior Fellow, Atlantic Council; Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University Joshua Kirschenbaum, Senior fellow at German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for Securing Democracy Richard Brooks, Financial investigative journalist for The Guardian and Private Eye magazine Panel II: The Magnitsky case Bill Browder, CEO and co-founder of Hermitage Capital Management Günter Schirmer, Head of the Secretariat of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe 2 29-01-2019 1-002-0000 IN THE CHAIR: PETR JEŽEK Chair of the Special Committee on Financial Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance (The meeting opened at 14.38) Panel I: Effects in the EU of money laundering cases involving Russian linkages 1-004-0000 Chair. – Good afternoon dear colleagues, dear guests, Ladies and Gentlemen. Let us start the public hearing of the Special Committee on Financial Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance (TAX3) on money-laundering cases involving Russian individuals and their effects on the EU. We will deal with the issue in two panels. On the first panel we are going to discuss the effects on the EU of money-laundering cases involving Russian linkages. Let me now introduce the speakers for the first panel. We welcome Mr Anders Åslund, who is a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council and Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University. -

Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 25 Putin’s Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket by John W. Parker Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier, August, 2012 (Russian Ministry of Defense) Putin's Syrian Gambit Putin's Syrian Gambit: Sharper Elbows, Bigger Footprint, Stickier Wicket By John W. Parker Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 25 Series Editor: Denise Natali National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. July 2017 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. -

March 2019 Newsnet

NewsNet News of the Association for Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies March 2019 v. 59, n. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Magnitsky Act - Behind the 3 Scenes: An interview with the film director, Andrei Nekrasov Losing Pravda, An Interview with 8 Natalia Roudakova Recent Preservation Projects 12 from the Slavic and East European Materials Project The Prozhito Web Archive of 14 Diaries: A Resource for Digital Humanists 17 Affiliate Group News 18 Publications ASEEES Prizes Call for 23 Submissions 28 In Memoriam 29 Personages 30 Institutional Member News Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) 203C Bellefield Hall, 315 S. Bellefield Ave Pittsburgh, PA 15260-6424 tel.: 412-648-9911 • fax: 412-648-9815 www.aseees.org ASEEES Staff Executive Director: Lynda Park 412-648-9788, [email protected] Communications Coordinator: Mary Arnstein 412-648-9809, [email protected] NewsNet Editor & Program Coordinator: Trevor Erlacher 412-648-7403, [email protected] Membership Coordinator: Sean Caulfield 412-648-9911, [email protected] Financial Support: Roxana Palomino 412-648-4049, [email protected] Convention Manager: Margaret Manges 412-648-4049, [email protected] 2019 ASEEES SUMMER CONVENTION 14-16 June 2019 Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb Zagreb, Croatia The 2019 ASEEES Summer Convention theme is “Culture Wars” with a focus on the ways in which individuals or collectives create or construct diametrically opposed ways of understanding their societies and their place in the world. As culture wars intensify across the globe, we invite participants to scrutinize present or past narratives of difference or conflict, and/or negotiating practices within divided societies or across national boundaries. -

Fusion GPS Interim

Gauhar, Tashina (ODAG) From: Gauhar, Tashina (ODAG) Sent: Monday, April 23, 2018 2:24 PM To: JCC (JMD) Subject: Scan into TS system Att achments: Pages from Binder1_KMF.PDF Howard - thanks for taking just now. As discussed, I need these emailsscanned onto the TS system and emailed to me. Can you let me know when completed and I will go into the SCI F. Thanks for your help, Tash Document ID: 0.7.17531.18512 20190701-0008383 OIUUN G. HATI:H. UTAH OW.NC f l'\,STll"• CAI ·001," u r,DSEY o. GRAHAM sovn, CAROU-'1A P.A I RICIC J t.11Y Vl'RM0'-1 JOH!, COl!'IYN. "'EXAS Ror•RO J DURerr, rwe,;oes ''ICIIAE, S. lff:. I.IT AH SH[d>ON v.~ TUIOUSE, AltOOE IS~ND TED CR\iZ. ll:XAS All!Y KI.OSXHAR.11!,Nt..'UOTA BE'I 5.ISSE. ll.£8AAS<A C~R.ISTOPHCR A C~'S. Dfl,t,W~ tinttrd iSmtc.s ~cnatc J(ff fl.AK(. AR1lONA RIC!iARO l!l.u,,r,.rhAI CQ",f;("'lC\/T " <E CRJl1'<l, aOA>tU Ml'l • , >lf<O"'O• HAW• I COMMITTEE ON THE J UDICIARY lttOM lu.tS.hOAT>ICAROI.IP.A COIIY A. IOOKC,. f..[~•1 JCR£L "'f JOHN KfN~EDV LO\,, S!ANA KA'JALI' I>. HAIIRIS, CAl,lfo;lt, A WASHINGTON. DC ,0610-6276 Kov.tJLOA\,tt..Cbw/Cows./~ dSl~H°'1ad<N .;1ro ...,,n ouc."' ~0t,..tf'",qm1.,;•f'tdSr•lfOr.-.ctJ:r February9,2018 VIA ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION PaulE.Hauser,Esq. Partner BryanCave 88WoodStreet London, EC2V7AJUK DearMr.Hauser: TheUnitedStatesSenateCommitteeon theJudiciaryhasbeeninvestigatingissues relatingtotheRussiangovernment’sdisinformation effortstargetingthe2016Presidential election,aswellas thenatureoftheFBI’srelationship withChristopherSteele. -

Un Asesino Silencioso…

UN ASESINO SILENCIOSO… El ex espía ruso Litvinenko muere envenenado 24.11.2006 - 07:22h LONDRES - El ex espía ruso Alexander Litvinenko murió el jueves en un hospital de Londres tres semanas después de ser envenenado en lo que sus amigos califican como un complot orquestado por el Kremlin. Rusia ha negado la acusación asegurando que es una tontería sugerir que Moscú quería asesinar Ilustración 1 - Alexander Litvinenko a Litvinenko, abiertamente crítico del presidente ruso, Vladimir Putin. La muerte se produjo la víspera de una cumbre entre la Unión Europea y Rusia en Helsinki, en la que Putin se enfrentará previsiblemente a preguntas de la prensa sobre el ex espía que podrían eclipsar la agenda principal sobre cómo pueden mejorar las relaciones entre ambas partes. Si se descubre que Rusia tuvo algo que ver en el envenenamiento, podría haber importantes consecuencias diplomáticas. Sería el primer incidente de este tipo en conocerse en Occidente desde la Guerra Fría. Scotland Yard informó el viernes de que ha hallado restos de una sustancia radiactiva en la casa del fallecido ex espía ruso Alexander Litvinenko, así como en un restaurante japonés y un hotel de Londres donde estuvo antes de enfermar. En concreto, la Policía ha encontrado rastros de polonio 210 (210Po), un isótopo del metal radiactivo polonio, también descubierto en la orina del antiguo agente secreto y considerado como la aparente causa de su supuesto envenenamiento. Se encontraron 14 sitios alrededor de Londres, un restaurante japonés, el hotel que visitó el día que cayó enfermo, 4 hoteles y 3 hospitales, aerolínea British Airways, Embajada británica en Moscú y un apartamento en Hamburgo (Alemania), con rastros de residuos radiactivos. -

Confidential May 31, 2016 Relations Between the United

Confidential May 31, 2016 Relations between the United States and the Russian Federation today are tense with disagreements, the origin of which lie in the international satisfaction granted by US lawmakers to a fugitive criminal accused of tax fraud in Russia, a former US citizen - William Browder who in 1998 renounced US citizenship for tax reasons. In December 2012, after a massive three-year lobbying campaign, the United States passed Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012 setting forth the never-existent story of a "lawyer" Sergey Magnitsky, who allegedly exposed corruption crimes and embezzlement from the Russian treasury, for which he was arrested, tortured and beaten to death in November 2009. This Act was in fact the beginning of a new round of the Cold War between the United States and Russia, putting on the scales the interests of a group of scammers and interstate relations. At the root of the Act is the story of Sergey Magnitsky, monstrous in its depth, which no one ever even took the trouble of verifying. According to open sources, the lob hying of the decision against Russia began in 2006, immediately after Browder was banned entry into Russia, several senators and public figures were involved in the process. In 2008, Browder officially announced a lobbying company on the issues between Hermitage Capital and Russia, and after the death of Magnitsky (synchronized with the need to focus attention on the problems of Hermitage Capital) - the lobbying campaign became known as the Magnitsky Act. In the course of the internal investigation into the reasons for providing political support to Browder in the United States, it was found that from the very beginning of the Hermitage Capital activities in Russia, spearheaded by its chief consultant Browder, the company's largest investor was Ziff Brothers Investments (a group of companies headed by three brothers - Dick, Robert, Daniel, billionaires from New York with serious ties in Washington. -

The Magnitsky Affair | by Amy Knight | the New York Review of Books 2/10/18, 3�39 PM

The Magnitsky Affair | by Amy Knight | The New York Review of Books 2/10/18, 339 PM The Magnitsky Affair Amy Knight FEBRUARY 22, 2018 ISSUE Last May, a money-laundering suit brought by the United States against Prevezon Holdings Ltd., a Cyprus-based real estate corporation, was unexpectedly settled three days before it was set to go to trial. The case had been at the center of a major international political controversy. Prevezon, which is owned by a Kremlin-connected Russian businessman named Denis Katsyv, was accused by the US government of using laundered money from a 2007 Russian tax fraud to buy millions of dollars’ worth of Manhattan real estate. The fraud, which was discovered by a Russian accountant named Sergei Magnitsky, involved companies owned by Hermitage Capital Management, a Moscow-based hedge fund run by the American-born British financier William Browder. In 2009, Magnitsky died in police custody, where he had Spencer Platt/Getty Images been held in abject conditions for nearly a year; three years President-elect Donald Trump with Ivanka Trump, Donald Trump Jr., and Vice President– elect Mike Pence at a news conference at Trump Tower, New York City, January 2017 later, President Obama signed legislation named after Magnitsky that placed heavy sanctions on numerous Russians involved in this affair. Several Russian lobbyists with close ties to the Kremlin have urged Donald Trump and members of Congress to reconsider those sanctions. “In view of recent revelations regarding Russia’s outsized influence,” William H. Pauley III, the presiding judge in the Prevezon trial, observed in November, “there may have been more to this money laundering case than a few luxury condominiums.” The Magnitsky affair begins with Browder. -

226 V a N I T Y F a I R a P R I L 2 0

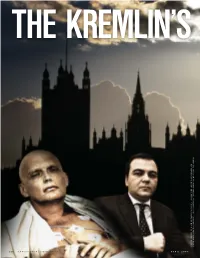

APRs IN not in yet.2/15please place. Text Revise ___________ Art Director ___________ Color Revise __________ THE KREMLIN’S ) O K N E , N ) I A V L T I L L E ( M Z A S R T I A E C S W ( A A J T S R A O T P A A N L , E ) R N I O T T U A P V ( L A V S O , K ) A N Y O N I D S N S O I L ( N E X D U , O ) V N E G Y I A G K N A A Z ( L A D I Y M B R S A I H P D A C R A G M O R T E O T H E P P 2 2 6 V A N I T Y F A I R www.vanityfair.com A P R I L 2 0 0 7 0044 SSPYPY PPOISONINGOISONING ll-o.vf.indd-o.vf.indd 1 22/26/07/26/07 55:41:30:41:30 PPMM 0407VF WE-54 APRs IN not in yet.2/15please place. Text Revise ___________ Art Director ___________ Color Revise __________ LONG SHADOW The sensational death of Russian dissident Alexander Litvinenko, poisoned by polonium 210 in London last November, is still being investigated by Scotland Yard. Many suspect the Kremlin. But interviewing the victim’s widow, fellow émigrés, and toxicologists, among others, BRYAN BURROUGH explores Litvinenko’s history with two powerful antagonists– one his bête noire, President Vladimir Putin, and the other his benefactor, exiled billionaire Boris Berezovsky–in a world where friends may be as dangerous as enemies FROM RUSSIA WITHOUT LOVE From left: Alexander Litvinenko at London’s University College Hospital on November 20, 2006, three days before his death; Italian security consultant Mario Scaramella; Chechen activist Akhmed Zakayev; Russian president Vladimir Putin. -

Combatting Cold War Tendencies and Rebuilding U.S.-Russian Relations

Combatting Cold War Tendencies and Rebuilding U.S.-Russian Relations By Rachel Bauman1 Published October 2016 1 Rachel Bauman is currently a Resident Junior Fellow at the Center for the National Interest. The author would like to thank those who helpfully contributed their insight, guidance, and time, particularly Samuel Charap, Matthew Rojansky, Eugene Rumer, and Paul Saunders. Introduction It is borne in upon me by several recent events… that try as I may, try as many others may, you will never succeed in establishing in American opinion a balanced & sensible view of Russia.2 George F. Kennan, writing at the end of 1986, predicted that negative perceptions of Russia would last long past the point of their relevance. Now, thirty years later, we see the unfortunate consequence of policymakers unthinkingly recapitulating Cold War tropes: a relationship with Russia which is strained to the point of snapping. True, the antagonism between Russia and the United States has deep historical roots, but its persistence belies deeper issues of political psychology and changing definitions of national interest and foreign policy priorities. This becomes evident through an examination of cooperative and hostile periods in the U.S.-Russian relationship. The demonization of Russia as, at worst, evil, or at best, a pitiable, backward nation, began in earnest during the fierce ideological competition of the Cold War, though differences between the two nations had been building in the decades prior. In addition to being institutionalized in policy, Russophobia has seeped into popular culture and has remained there, virtually unquestioned, ever since. To be sure, the Russian government is propagating a steady stream of anti-American propaganda as well, and though neither side bears complete responsibility for the deterioration in relations, the United States would be wise to rethink its approach to Russia and analyze the extent to which our own behavior has driven Russia’s decision-making. -

March 31, 2017 VIA ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION the Honorable

March 31, 2017 VIA ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION The Honorable Dana Boente Acting Deputy Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20530 Dear Mr. Boente: Over the past few years, the Committee has repeatedly contacted the Department of Justice to raise concerns about the Department’s lack of enforcement of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (“FARA”). I write regarding the Department’s response to the alleged failure of pro-Russia lobbyists to register under FARA. In July of 2016, Mr. William Browder filed a formal FARA complaint with the Justice Department regarding Fusion GPS, Rinat Akhmetshin, and their associates.1 His complaint alleged that lobbyists working for Russian interests in a campaign to oppose the pending Global Magnitsky Act failed to register under FARA and the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995. The Committee needs to understand what actions the Justice Department has taken in response to the information in Mr. Browder’s complaint. The issue is of particular concern to the Committee given that when Fusion GPS reportedly was acting as an unregistered agent of Russian interests, it appears to have been simultaneously overseeing the creation of the unsubstantiated dossier of allegations of a conspiracy between the Trump campaign and the Russians. Mr. Browder is the CEO of Hermitage Capital Management (“Hermitage”), an investment firm that at one time was the largest foreign portfolio investor in Russia. According to the Justice Department, in 2007, Russian government officials and members of organized crime engaged in corporate identity theft, stealing the corporate identities of three Hermitage companies and using them to fraudulently obtain $230 million.2 The $230 million was then extensively laundered into accounts outside of Russia. -

Российские Кинопрограммы Russian Film Programs

МОСКОВСКИЙ МЕЖДУНАРОДНЫЙ КИНОФЕСТИВАЛЬ 43 MOSCOW INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL РОССИЙСКИЕ КИНОПРОГРАММЫ RUSSIAN FILM PROGRAMS НОВОЕ РОССИЙСКОЕ КИНО NEW RUSSIAN CINEMA ДЕБЮТЫ DEBUTS НОВОЕ ДОКУМЕНТАЛЬНОЕ КИНО NEW RUSSIAN DOCUMENTARY НОВАЯ РОССИЙСКАЯ АНИМАЦИЯ NEW RUSSIAN ANIMATION ПАНОРАМА КОРОТКОГО МЕТРА THE PANORAMA OF SHORTS СПЕЦИАЛЬНОЕ СОБЫТИЕ «ГРИГОРИЙ ЧУХАЙ. 100 ЛЕТ» SPECIAL EVENT GRIGORIY CHUKHRAY. 100 YEARS © МЕДИАФЕСТ, при поддержке Министерства культуры Российской Федерации, ООО «Союза кинематографистов России» © MEDIAFEST with assistance of Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation, Filmmakers’ Union of the Russian Federation CОДЕРЖАНИЕ НОВОЕ РОССИЙСКОЕ КИНО КОНЬ ЮЛИЙ И БОЛЬШИЕ СКАЧКИ . .ШМИДТ ДАРИНА, # ТОЛЬКО СЕРЬЕЗНЫЕ ОТНОШЕНИЯ . .РОСС СЛАВА . .6 . .ФЕОКТИСТОВ КОНСТАНТИН . .90 АРХИПЕЛАГ . .ТЕЛЬНОВ АЛЕКСЕЙ, ЛАЙК . .ЖУРАВЛЕВА АНАСТАСИЯ . .91 . .МАЛАХОВ (МЛ.) МИХАИЛ . .8 МЕДВЕДЬ . .УШАКОВ СВЯТОСЛАВ . .92 ВМЕШАТЕЛЬСТВО . .ЗУЕВА КСЕНИЯ . .10 МОКРЫЕ НОСОЧКИ БЕРТЫ РАЙЗ . .ШАДРИНА АЛЕКСАНДРА . .93 ДУША ПИРАТА . .ЮМАГУЛОВ АЙСЫУАК . .12 О, НЕЕТ! . .МАКСИМОВ ИВАН . .94 КОНЕЦ ФИЛЬМА . .КОТТ ВЛАДИМИР . .14 ОГОНЕКJОГНИВО . .ЩЁКИН КОНСТАНТИН . .95 КОНФЕРЕНЦИЯ . .ТВЕРДОВСКИЙ ИВАН И. .16 ПАНДЕМИЯ . .КАМПИОНИ ПОЛИНА . .96 КТОJНИБУДЬ ВИДЕЛ МОЮ ДЕВЧОНКУ? . .НИКОНОВА АНГЕЛИНА . .18 ПОД ОБЛАКАМИ . .ТИКУНОВА ВАСИЛИСА . .97 ПАЛЬМА . .ДОМОГАРОВ МЛ. АЛЕКСАНДР . .20 ПОЖАРНИК . .АРОНОВА ЮЛИЯ . .98 РОДНЫЕ . .АКСЕНОВ ИЛЬЯ . .22 ПРИВЕТ, БАБУЛЬНИК! . .МИРЗОЯН НАТАША . .99 СЕВЕРНЫЙ ВЕТЕР . .ЛИТВИНОВА РЕНАТА . .24 ПРИНЦЕССА И БАНДИТ . .СОСНИНА МАРИЯ, СКАЖИ ЕЙ . .МОЛОЧНИКОВ АЛЕКСАНДР . .26 . .АЛДАШИН МИХАИЛ . .100 ЭСАВ . .ЛУНГИН ПАВЕЛ . .28 САХАРНОЕ ШОУ . .МАКАРЯН ЛИАНА . .101 ТАТЬ . .УЛЬЯНОВА ЕКАТЕРИНА . .102 ДЕБЮТЫ ТЕПЛАЯ ЗВЕЗДА . .КУЗИНА АННА . .103 АНИМАЦИЯ . .СЕРЁГИН СЕРГЕЙ . .32 УТОЧКА И КЕНГУРУ . .СКВОРЦОВА ЛИЗА . .104 ИВАНОВО СЧАСТЬЕ . .СОСНИН ИВАН . .34 ЯБЛОНЕВЫЙ ЧЕЛОВЕК . .ВАРТАНЯН АЛЛА . .105 МАЛЕНЬКИЙ ВОИН . .ЕРМОЛОВ ИЛЬЯ . .36 НЕ НАЗЫВАЙ МЕНЯ ВАСЯ . .ШАКИРЗЯНОВА АЛЬФИЯ . .38 ПАНОРАМА КОРОТКОГО МЕТРА ПЕЧЕНЬ ИЛИ ИСТОРИЯ ОДНОГО СТАРТАПА . -

Directors in Competition Directors in Competition

XXXXXXXDIRECTORS IN COMPETITION DIRECTORS IN COMPETITION JOEL AUTIO Karolina BrobÄCK MARIA ERIKSSON KIRA RICHARDS HANSEN FILMMAKER FILMMAKER FIMMAKER FILMMAKER Joel graduated from Turku Arts Brobäck is a Swedish visual artist. She Maria Eriksson has hit the ground Kira studied directing in England at Academy Film School in 2014. studied Animation & Experimental running as a filmmaker. She The Arts Institute of Bournemouth Film and began working with Atmo graduated from Stockholm Academy and has a MA in film studies from in 2008 with Tarik Saleh’s Metropia. of Dramatic Arts with her successful the University of Copenhagen. She She has also been assistant director to short film Annalyn, which has been directed the short film Damn Girl, Tarik Saleh and Stefan Constantinescu. screened at many festivals all over winner of 8 Awards including Best Seat 26D is her directing debut. the world and won numerous prizes. Short Film at BUFF 2013. EVEN G. Benestad Maria brings grit, honesty and flavour to her films with She is currently in post-production with a new short FILMMAKER JENS DAHL spellbinding performances and moving stories dealing film called Recognition. Her film Wayward premiered at Even studied cinematography at the FILMMAKER with sexuality, love, family and friendship. CPH:PIX 2014. Oslo Film and Television Academy. For more than 15 years, Jens He made his first feature-length Dahl has been one of the key YRSA ROCA Fannberg AUGUST B. HANSSEN documentary All About My Father in screenwriters in Denmark. He FILMMAKER FILMMAKER 2002. The film was screened at more co-wrote the screenplay for Nicolas Yrsa has a degree in Fine Arts from August has co-directed three than 100 film festivals and received Winding Refn’s Pusher, which was London’s Chelsea College of Art and films with long time collaborator national and international acclaim.