And Food-Resource-Dependent Courtship Behaviour in Poecilobothrus Nobilitatus 123

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetics of the Spiroplasma Ixodetis

Phylogenetics of the Spiroplasma ixodetis endosymbiont reveals past transfers between ticks and other arthropods Florian Binetruy, Xavier Bailly, Christine Chevillon, Oliver Martin, Marco Bernasconi, Olivier Duron To cite this version: Florian Binetruy, Xavier Bailly, Christine Chevillon, Oliver Martin, Marco Bernasconi, et al.. Phylogenetics of the Spiroplasma ixodetis endosymbiont reveals past transfers between ticks and other arthropods. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases, Elsevier, 2019, 10 (3), pp.575-584. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.02.001. hal-02151790 HAL Id: hal-02151790 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02151790 Submitted on 23 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Title: Phylogenetics of the Spiroplasma ixodetis endosymbiont reveals past transfers between ticks and other arthropods Authors: Florian Binetruy, Xavier Bailly, Christine Chevillon, Oliver Y. Martin, Marco V. Bernasconi, Olivier Duron PII: S1877-959X(18)30403-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.02.001 Reference: TTBDIS 1167 To appear in: Received date: 25 September 2018 Revised date: 10 December 2018 Accepted date: 1 February 2019 Please cite this article as: Binetruy F, Bailly X, Chevillon C, Martin OY, Bernasconi MV, Duron O, Phylogenetics of the Spiroplasma ixodetis endosymbiont reveals past transfers between ticks and other arthropods, Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases (2019), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.02.001 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. -

Sensory Ecology and Neural Coding in Arthropods*

Sensory Ecology and Neural Coding in Arthropods* Martin Egelhaaf, Roland Kern and Anne-Kathrin Warzecha Lehrstuhl für Neurobiologie, Fakultät für Biologie, Universität Bielefeld, Postfach 10 01 31, D-33501 Bielefeld, Germany Z. Naturforsch. 53c, 582-592 (1998); received April 9, 1998 Sensory Ecology, Behaviour, Neural Coding, Vision, Arthropods Arthropods live in almost any conceivable habitat. Accordingly, structural and functional specialisations have been described in many species which allow them to behave in an adap tive way with the limited computational resources of their small brains. These adaptations range from the special design of the eyes, the spectral sensitivities of their photoreceptors to the specific properties of neural circuits. Introduction an adaptation, if it is necessary for solving a partic Organisms can be found in almost any habitat, ular task which can otherwise not be solved. This however harsh it may appear to humans. Since or is hardly ever the case, as there might be usually ganisms are the outcome of a long evolutionary other solutions to the task. We may only under process, they are generally conceived to be stand the significance of functional specialisations, adapted by natural selection to their respective en if we realise that no animal species can live every vironments. These adaptations manifest them where. Rather any environment is likely to be selves in all sorts of structural and functional spe structured in a characteristic way, thus constrain cialisations. Of course, also the behaviour of ing the sensory input an animal can expect to re animals as well as the underlying neuronal ma ceive during its lifetime. -

Diptera: Dolichopodidae) and the Significance of Morphological Characters Inferred from Molecular Data

Eur. J. Entomol. 104: 601–617, 2007 http://www.eje.cz/scripts/viewabstract.php?abstract=1264 ISSN 1210-5759 Phylogeny of European Dolichopus and Gymnopternus (Diptera: Dolichopodidae) and the significance of morphological characters inferred from molecular data MARCO VALERIO BERNASCONI1*, MARC POLLET2,3, MANUELA VARINI-OOIJEN1 and PAUL IRVINE WARD1 1Zoologisches Museum, Universität Zürich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, CH-8057 Zürich, Switzerland; e-mail: [email protected] 2Research Group Terrestrial Ecology, Department of Biology, Ghent University (UGent), K.L.Ledeganckstraat 35, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium 3Department of Entomology, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (KBIN), Vautierstraat 29, B-1000 Brussels, Belgium Key words. Diptera, Dolichopodidae, Dolichopus, Ethiromyia, Gymnopternus, Europe, mitochondrial DNA, cytochrome oxidase I, cytochrome b, morphology, ecology, distribution Abstract. Dolichopodidae (over 6000 described species in more than 200 genera) is one of the most speciose families of Diptera. Males of many dolichopodid species, including Dolichopus, feature conspicuous ornaments (Male Secondary Sexual Characters) that are used during courtship. Next to these MSSCs, every identification key to Dolichopus primarily uses colour characters (postocular bristles; femora) of unknown phylogenetic relevance. The phylogeny of Dolichopodidae has rarely been investigated, especially at the species level, and molecular data were hardly ever involved. We inferred phylogenetic relationships among 45 species (57 sam- ples) of the subfamily Dolichopodinae on the basis of 32 morphological and 1415 nucleotide characters (810 for COI, 605 for Cyt-b). The monophyly of Dolichopus and Gymnopternus as well as the separate systematic position of Ethiromyia chalybea were supported in all analyses, confirming recent findings by other authors based purely on morphology. -

Diptera) in a Wetland Habitat and Their Potential Role As Bioindicators

Cent. Eur. J. Biol. • 6(1) • 2011 • 118–129 DOI: 10.2478/s11535-010-0098-x Central European Journal of Biology Ecology of Dolichopodidae (Diptera) in a wetland habitat and their potential role as bioindicators Research Article Ivan Gelbič*, Jiří Olejníček Biological Centre of Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Entomology, CZ 370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic Received 28 April 2010; Accepted 06 September 2010 Abstract: Ecologicalinvestigationsoflong-leggedflies(Dolichopodidae)werecarriedoutinwetmeadowwetlandsnearČeskéBudějovice, Czech Republic. Sampling was performed during the adult flies’ seasonal activity (March-October) in 2002, 2003 and 2004 using yellow pan traps, Malaise traps, emergence traps, and by sweeping. Altogether 5,697 specimens of 78 species of Dolichopodidae were collected, identified and analysed. The study examined community structure, species abundance, and diversity(Shannon-Weaver’sindex-H’;Sheldon’sequitabilityindex-E).Chrysotus cilipes,C. gramineus and Dolichopus ungulatus were the most abundant species in all three years. Species richness and diversity seem strongly affected by soil moisture. Keywords: Long-legged Flies • Ecology • Conservation • Bioindication ©VersitaSp.zo.o. usually do not fly too far from their breeding places, 1. Introduction which is convenient for their use as bioindicators. The Dolichopodid flies represent a good model for the study aims of this paper are (i) to extend our knowledge on of bioindication because they meet all necessary criteria the community structure of dolichopodid fauna and for this role [1]. Pollet has indicated four such criteria: (ii) to explore possibilities for the use of these insects as 1) easy determination of species, 2) a taxonomic bio-indicators. group comprised of a sufficient number of species, 3) satisfactory knowledge about ecology/biology of the species, and 4) species should reveal specific ecological 2. -

Manual of the Families and Genera of North American Diptera

iviobcow,, Idaho. tvl • Compliments of S. W. WilliSTON. State University, Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A. Please acknowledge receipt. \e^ ^ MANUAL FAMILIES AND GENERA ]^roRTH American Diptera/ SFXOND EDITION REWRITTEN AND ENLARGED SAMUEL W^' WILLISTON, M.D., Ph.D. (Yale) PROFESSOR OF PALEONTOLOGY AND ANATOMY UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS AUG 2 1961 NEW HAVEN JAMES T. HATHAWAY 297 CROWN ST. NEAR YALE COLLEGE 18 96 Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1896, Bv JAMES T. HATHAWAY, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. PREFACE Eight years ago the author of the present work published a small volume in which he attempted to tabulate the families and more important genera of the diptera of the United States. From the use that has been made of that work by etitomological students, he has been encouraged to believe that the labor of its preparation was not in vain. The extra- ordinary activity in the investigation of our dipterological fauna within the past few years has, however, largely destroy- ed its usefulness, and it is hoped that this new edition, or rather this new work, will prove as serviceable as has been the former one. In the present work there has been an at- tempt to include all the genera now known from north of South America. While the Central and West Indian faunas are preeminently of the South American type, there are doubt- less many forms occurring in tlie southern states that are at present known only from more southern regions. In the preparation of the work the author has been aided by the examination, so far as he was able, of extensive col- lections from the West Indies and Central America submitted to him for study by Dr. -

MJBS 17(1).Indd

© 2019 Journal compilation ISSN 1684-3908 (print edition) http://mjbs.num.edu.mn Mongolian Journal of Biological http://biotaxa.org./mjbs Sciences MJBS Volume 17(1), 2019 ISSN 2225-4994 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.22353/mjbs.2019.17.04 Original Ar cle Wing Shape in the Taxonomic Identifi cation of Genera and Species of the Subfamily Dolichopodinae (Dolichopodidae, Diptera) Mariya A. Chursina Voronezh State University, Universitetskaya sq., 1, 394006 Voronezh, Russia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Key words: Diptera, Characters of the wing morphology have signifi cant importance in the systematics Dolichopodidae, wing and taxonomy of the family Dolichopodidae, but there are only a few studies shape, geometric concerning the variation in wing shape of dolichopodid fl ies. The detailed analysis morphometric analysis, of interspecifi c and generic wing shape variation can provide data for the taxonomic interspecifi c variation, studies, and understanding of the selective forces shaping wing morphometric taxonomy. characters is important for studying of their pattern of evolutionary change. A geometric morphometric analysis was carried out on 72 species belonging to 5 genera Article information: of the subfamily Dolichopodinae in order to determine whether wing shape can be Received: 01 May 2019 successfully used as a character for taxonomic discrimination of morphologically Accepted: 06 June 2019 similar genera and species. Canonical variate analysis based on wing shape data Published online: showed signifi cant diff erences among the studied genera and species. Discriminant 02 July 2019 analysis allowed for the correct genera identifi cation from 74.50% to 91.58% specimens. The overall success for the reassignment of specimens to their a priori species group was on average 84.04%. -

June, 1997 ORNAMENTS in the DIPTERA

142 Florida Entomologist 80(2) June, 1997 ORNAMENTS IN THE DIPTERA JOHN SIVINSKI USDA, ARS, Center for Medical, Agricultural and Veterinary Entomology Gainesville, FL 32604 ABSTRACT Occasionally, flies bear sexually dimorphic structures (ornaments) that are used, or are presumed to be used, in courtships or in aggressive interactions with sexual ri- vals. These are reviewed, beginning with projections from the head, continuing through elaborations of the legs and finishing with gigantism of the genitalia. Several functions for ornaments are considered, including advertisement of genetic proper- ties, subversion of female mate choice and “runaway” sexual selection. Neither the type of ornament nor the degree of elaboration necessarily indicates which of the above processes is responsible for a particular ornament. Resource distribution and the resulting possibilities for resource defense and mate choice explain the occurrence of ornaments in some species. The phyletic distribution of ornaments may reflect for- aging behaviors and the type of substrates upon which courtships occur. Key Words: sexual selection, territoriality, female mate choice, arms races RESUMEN Ocasionalmente, las moscas presentan estructuras sexuales dimórficas (ornamen- tos) que son utilizados o se cree sean utilizadas en el cortejo sexual o en interacciones agresivas con sus rivales sexuales. Dichas estructuras han sido evaluadas, comen- zando con proyecciones de la cabeza, continuando con las estructuras elaboradas de las extremidades y terminando con el gigantismo de los genitales. Se han considerado distintas funciones para dichos ornamentos, incluyendo la promoción de sus propie- dades genéticas, subversión de la elección de la hembra por aparearse, y el rehusare a la selección sexual. Tanto el tipo de ornamento como el grado de elaboración no ne- cesariamente indicaron cual de los procesos mencionados es el responsable de un or- namento en particular. -

Dipterists Forum Events

BULLETIN OF THE Dipterists Forum Bulletin No. 73 Spring 2012 Affiliated to the British Entomological and Natural History Society Bulletin No. 73 Spring 2012 ISSN 1358-5029 Editorial panel Bulletin Editor Darwyn Sumner Assistant Editor Judy Webb Dipterists Forum Officers Chairman Martin Drake Vice Chairman Stuart Ball Secretary John Kramer Meetings Treasurer Howard Bentley Please use the Booking Form included in this Bulletin or downloaded from our Membership Sec. John Showers website Field Meetings Sec. Roger Morris Field Meetings Indoor Meetings Sec. Malcolm Smart Roger Morris 7 Vine Street, Stamford, Lincolnshire PE9 1QE Publicity Officer Judy Webb [email protected] Conservation Officer Rob Wolton Workshops & Indoor Meetings Organiser Malcolm Smart Ordinary Members “Southcliffe”, Pattingham Road, Perton, Wolverhampton, WV6 7HD [email protected] Chris Spilling, Duncan Sivell, Barbara Ismay Erica McAlister, John Ismay, Mick Parker Bulletin contributions Unelected Members Please refer to later in this Bulletin for details of how to contribute and send your material to both of the following: Dipterists Digest Editor Peter Chandler Dipterists Bulletin Editor Darwyn Sumner Secretary 122, Link Road, Anstey, Charnwood, Leicestershire LE7 7BX. John Kramer Tel. 0116 212 5075 31 Ash Tree Road, Oadby, Leicester, Leicestershire, LE2 5TE. [email protected] [email protected] Assistant Editor Treasurer Judy Webb Howard Bentley 2 Dorchester Court, Blenheim Road, Kidlington, Oxon. OX5 2JT. 37, Biddenden Close, Bearsted, Maidstone, Kent. ME15 8JP Tel. 01865 377487 Tel. 01622 739452 [email protected] [email protected] Conservation Dipterists Digest contributions Robert Wolton Locks Park Farm, Hatherleigh, Oakhampton, Devon EX20 3LZ Dipterists Digest Editor Tel. -

Nomenclatural Studies Toward a World List of Diptera Genus-Group Names

Nomenclatural studies toward a world list of Diptera genus-group names. Part II Camillo Rondani O'Hara, James E.; Cerretti, Pierfilippo; Pape, Thomas; Evenhuis, Neal L. Publication date: 2011 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY Citation for published version (APA): O'Hara, J. E., Cerretti, P., Pape, T., & Evenhuis, N. L. (2011). Nomenclatural studies toward a world list of Diptera genus-group names. Part II: Camillo Rondani. Magnolia Press. Zootaxa Vol. 3141 http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/2011/f/zt03141p268.pdf Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Zootaxa 3141: 1–268 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) ZOOTAXA 3141 Nomenclatural Studies Toward a World List of Diptera Genus-Group Names. Part II: Camillo Rondani JAMES E. O’HARA1, PIERFILIPPO CERRETTI2, THOMAS PAPE3 & NEAL L. EVENHUIS4 1. Canadian National Collection of Insects, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 960 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0C6, Canada; email: [email protected] 2. Centro Nazionale Biodiversità Forestale “Bosco Fontana”, Corpo Forestale dello Stato, Via C. Ederle 16/A, 37100 Verona, Italy; email: [email protected] 3. Natural History Museum of Denmark, Universitetsparken 15, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark; email: [email protected] 4. J. Linsley Gressitt Center for Entomological Research, Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawaii 96817-2704, USA; email: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by D. Bickel: 09 Nov. 2011; published: 23 Dec. 2011 Nomenclatural Studies Toward a World List of Diptera Genus-Group Names. -

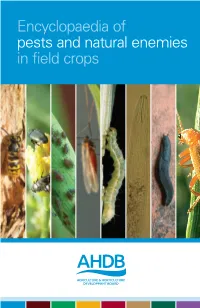

Encyclopaedia of Pests and Natural Enemies in Field Crops Contents Introduction

Encyclopaedia of pests and natural enemies in field crops Contents Introduction Contents Page Integrated pest management Managing pests while encouraging and supporting beneficial insects is an Introduction 2 essential part of an integrated pest management strategy and is a key component of sustainable crop production. Index 3 The number of available insecticides is declining, so it is increasingly important to use them only when absolutely necessary to safeguard their longevity and Identification of larvae 11 minimise the risk of the development of resistance. The Sustainable Use Directive (2009/128/EC) lists a number of provisions aimed at achieving the Pest thresholds: quick reference 12 sustainable use of pesticides, including the promotion of low input regimes, such as integrated pest management. Pests: Effective pest control: Beetles 16 Minimise Maximise the Only use Assess the Bugs and aphids 42 risk by effects of pesticides if risk of cultural natural economically infestation Flies, thrips and sawflies 80 means enemies justified Moths and butterflies 126 This publication Nematodes 150 Building on the success of the Encyclopaedia of arable weeds and the Encyclopaedia of cereal diseases, the three crop divisions (Cereals & Oilseeds, Other pests 162 Potatoes and Horticulture) of the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board have worked together on this new encyclopaedia providing information Natural enemies: on the identification and management of pests and natural enemies. The latest information has been provided by experts from ADAS, Game and Wildlife Introduction 172 Conservation Trust, Warwick Crop Centre, PGRO and BBRO. Beetles 175 Bugs 181 Centipedes 184 Flies 185 Lacewings 191 Sawflies, wasps, ants and bees 192 Spiders and mites 197 1 Encyclopaedia of pests and natural enemies in field crops Encyclopaedia of pests and natural enemies in field crops 2 Index Index A Acrolepiopsis assectella (leek moth) 139 Black bean aphid (Aphis fabae) 45 Acyrthosiphon pisum (pea aphid) 61 Boettgerilla spp. -

Hypotheses from Mitochondrial DNA: Congruence and Conflict Between DNA Sequences and Morphology in Dolichopodinae Systematics (Diptera : Dolichopodidae)

Pollet, M; Germann, C; Tanner, S; Bernasconi, M V (2010). Hypotheses from mitochondrial DNA: congruence and conflict between DNA sequences and morphology in Dolichopodinae systematics (Diptera : Dolichopodidae). Invertebrate Systematic, 24(1):32-50. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Invertebrate Systematic 2010, 24(1):32-50. Winterthurerstr. 190 CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2010 Hypotheses from mitochondrial DNA: congruence and conflict between DNA sequences and morphology in Dolichopodinae systematics (Diptera : Dolichopodidae) Pollet, M; Germann, C; Tanner, S; Bernasconi, M V Pollet, M; Germann, C; Tanner, S; Bernasconi, M V (2010). Hypotheses from mitochondrial DNA: congruence and conflict between DNA sequences and morphology in Dolichopodinae systematics (Diptera : Dolichopodidae). Invertebrate Systematic, 24(1):32-50. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Invertebrate Systematic 2010, 24(1):32-50. Hypotheses from mitochondrial DNA: congruence and conflict between DNA sequences and morphology in Dolichopodinae systematics (Diptera: Dolichopodidae) Marc Pollet1,2,3, Christoph Germann4, Samuel Tanner4#, & Marco Valerio Bernasconi*4 1Department of Entomology, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS), Vautierstraat 29, B-1000 Brussels (Belgium) 2Research Group Terrestrial Ecology (TEREC), Department of Biology, Ghent University (UGent), K.L.Ledeganckstraat 35, B-9000 Ghent (Belgium) 3Information and Data Center, Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO), Kliniekstraat 25, B-1070 Brussels (Belgium) 4Zoological Museum, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, CH-8057 Zurich, Switzerland #Present Address: Space Biology Group / BIOTESC, ETH Zurich / Technopark, Technoparkstr. -

An Introduction to the Immature Stages of British Flies

Royal Entomological Society HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS To purchase current handbooks and to download out-of-print parts visit: http://www.royensoc.co.uk/publications/index.htm This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Copyright © Royal Entomological Society 2013 Handbooks for the Identification of British Insects Vol. 10, Part 14 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE IMMATURE STAGES OF BRITISH FLIES DIPTERA LARVAE, WITH NOTES ON EGGS, PUP ARIA AND PUPAE K. G. V. Smith ROYAL ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON Handbooks for the Vol. 10, Part 14 Identification of British Insects Editors: W. R. Dolling & R. R. Askew AN INTRODUCTION TO THE IMMATURE STAGES OF BRITISH FLIES DIPTERA LARVAE, WITH NOTES ON EGGS, PUPARIA AND PUPAE By K. G. V. SMITH Department of Entomology British Museum (Natural History) London SW7 5BD 1989 ROYAL ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON The aim of the Handbooks is to provide illustrated identification keys to the insects of Britain, together with concise morphological, biological and distributional information. Each handbook should serve both as an introduction to a particular group of insects and as an identification manual. Details of handbooks currently available can be obtained from Publications Sales, British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD. Cover illustration: egg of Muscidae; larva (lateral) of Lonchaea (Lonchaeidae); floating puparium of Elgiva rufa (Panzer) (Sciomyzidae). To Vera, my wife, with thanks for sharing my interest in insects World List abbreviation: Handbk /dent. Br./nsects. © Royal Entomological Society of London, 1989 First published 1989 by the British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD.