Pirates and Emperors (Claremont, 1986)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi Writes About Henry David Thoreau Source 2

Handout Source 1: Gandhi writes about Henry David Thoreau Many years ago, there lived in America a great man named Henry David Thoreau. His writings are read and pondered over by millions of people… Much importance is attached to his writings because Thoreau himself was a man who practised what he preached. Impelled by a sense of duty, he wrote much against his own country, America. He considered it a great sin that the Americans held many persons in the bond of slavery. He did not rest content with saying this, but took all other necessary steps to put a stop to this trade. One of the steps consisted in not paying any taxes to the State in which the slave trade was being carried on. He was imprisoned when he stopped paying the taxes due from him. The thoughts which occurred to him during his imprisonment were boldly original. [From Gandhi. Indian Opinion. Quoted in M.V. Kamath. The United States and India 1776-1976. Washington, D.C.: Embassy of India, 1976. 65.] Source 2: Gandhi’s Influence on Dr. Martin Luther King When King arrived one cold day in New Delhi, as a guest of the Government of India, his first words were a tribute to Gandhi. “To other countries,” King said, “I may go as a tourist, but to India I come as a pilgrim. This is because India means to me Mahatma Gandhi, a truly great man of the age.” King heard of Gandhi from Dr. Mordecai Johnson, President of Howard University, who had returned from a visit to India and was speaking at Philadelphia. -

Civil Disobedience

Civil Disobedience Henry David Toreau Civil Disobedience Henry David Toreau Foreword by Connor Boyack Libertas Institute Salt Lake City, Utah Civil Disobedience Thoreau’s essay is out of copyright and in the public domain; this version is lightly edited for modernization. Supplemental essays are copyrighted by their respective authors and included with permission. The foreword is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. LIBERTAS PRESS 770 E. MAIN STREET, SUITE 255 LEHI, UT 84043 Civil Disobedience / Henry David Toreau — 1st ed. First printing, June 2014 Cover Design by Ben Jenkins Manufactured in the United States of America For bulk orders, send inquiries to: [email protected] ISBN-13: 978-0-9892912-3-1 dedicated to Edward Snowden for doing what was right “Te most foolish notion of all is the belief that everything is just which is found in the customs or laws of nations. Would that be true, even if these laws had been enacted by tyrants?” “What of the many deadly, the many pestilential statutes which nations put in force? Tese no more deserve to be called laws than the rules a band of robbers might pass in their assembly. For if ignorant and unskillful men have prescribed deadly poisons instead of healing drugs, these cannot possibly be called physicians’ prescriptions; neither in a nation can a statute of any sort be called a law, even though the nation, in spite of being a ruinous regulation, has accepted it.” —Cicero Foreword by Connor Boyack Americans know Henry David Thoreau as the author of Walden, a narrative published in 1854 detailing the author’s life at Walden Pond, on property owned by his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson near Concord, Massachusetts. -

A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 6-11-2009 A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau Jack Turner University of Washington Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Turner, Jack, "A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau" (2009). Literature in English, North America. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/70 A Political Companion to Henr y David Thoreau POLITIcaL COMpaNIONS TO GREat AMERIcaN AUthORS Series Editor: Patrick J. Deneen, Georgetown University The Political Companions to Great American Authors series illuminates the complex political thought of the nation’s most celebrated writers from the founding era to the present. The goals of the series are to demonstrate how American political thought is understood and represented by great Ameri- can writers and to describe how our polity’s understanding of fundamental principles such as democracy, equality, freedom, toleration, and fraternity has been influenced by these canonical authors. The series features a broad spectrum of political theorists, philoso- phers, and literary critics and scholars whose work examines classic authors and seeks to explain their continuing influence on American political, social, intellectual, and cultural life. This series reappraises esteemed American authors and evaluates their writings as lasting works of art that continue to inform and guide the American democratic experiment. -

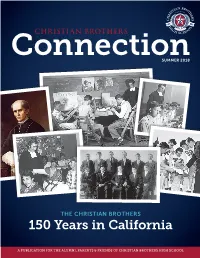

Connection – Summer 2018

ConnectionCHRISTIAN BROTHERS SUMMER 2018 THE CHRISTIAN BROTHERS 150 Years in California A PUBLICATION FOR THE ALUMNI, PARENTS & FRIENDS OF CHRISTIAN BROTHERS HIGH SCHOOL CB Leadership Team Lorcan P. Barnes President Chris Orr Principal June McBride Board of Trustees Director of Finance David Desmond ’94 The Board of Trustees at Christian Brothers High School is comprised of 11 volunteers Assistant Principal dedicated to safeguarding and advancing the school’s Lasallian Catholic college preparatory mission. Before joining the Board of Trustees, candidates undergo Michelle Williams training on Lasallian charism (history, spirituality and philosophy of education) and Assistant Principal Policy Governance, a model used by Lasallian schools throughout the District of Myra Makelim San Francisco New Orleans. In the 2017–18 school year, the board welcomed two new Human Resources Director members, Marianne Evashenk and Heidi Harrison. David Walrath serves in the role of chair and Mr. Stephen Mahaney ’69 is the vice chair. Kristen McCarthy Director of Admissions & The Policy Governance model comprises an inclusive, written set of goals for the school, Communications called Ends Policies, which guide the board in monitoring the performance of the school through the President/CEO. Ends Policies help ensure that Christian Brothers High Nancy Smith-Fagan School adheres to the vision of the Brothers of the Christian Schools and the District Director of Advancement of San Francisco New Orleans. “The Board thanks the families who have entrusted their children to our school,” says Chair David Walrath. “We are constantly amazed by our unbelievable students. They are creative, hardworking and committed to the Lasallian Core Principles. Assisting Connection is a publication of these students are the school’s faculty, staff and administration. -

Full Press Release

Press Contacts Michelle Perlin 212.590.0311, [email protected] aRndf Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] THE LIFE OF HENRY DAVID THOREAU THROUGH THE LENS OF HIS REMARKABLE JOURNAL IS THE SUBJECT OF A NEW MORGAN EXHIBITION This Ever New Self: Thoreau and His Journal June 2 through September 10, 2017 New York, NY, April 17, 2017 — Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) occupies a lofty place in American cultural history. He spent two years in a cabin by Walden Pond and a single night in jail, and out of those experiences grew two of this country’s most influential works: his book Walden and the essay known as “Civil Disobedience.” But his lifelong journal—more voluminous by far than his published writings—reveals a fuller, more intimate picture of a man of wide-ranging interests and a profound commitment to living responsibly and passionately. Now, in a major new exhibition entitled This Ever New Self: Thoreau and His Journal opening June 2 at the Morgan Library & Museum, nearly one hundred items Benjamin D. Maxham (1821–1889), Henry D. Thoreau, have been brought together in the most comprehensive Daguerreotype, Worcester, Massachusetts, June 18, 1856. Berg Collection, New York Public Library. exhibition ever devoted to the author. Marking the 200th anniversary of his birth and organized in partnership with the Concord Museum in Thoreau’s hometown of Concord, Massachusetts, the show centers on the journal he kept throughout his life and its importance in understanding the essential Thoreau. More than twenty of Thoreau’s journal notebooks are shown along with letters and manuscripts, books from his library, pressed plants from his herbarium, and important personal artifacts. -

Library of Congress Collections Policy Statements: Psychology

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS COLLECTIONS POLICY STATEMENTS ±² Collections Policy Statement Index Psychology (Classes BF and Z7201-Z7204, with some Z8000s) Contents I. Scope II. Research strengths III. Collecting Policy IV. Acquisition Sources: Current and Future V. Collecting levels I. Scope The materials on psychology covered by this statement comprise physical collections in Class BF, with corresponding subject bibliographies in Z7201-7204, and also electronic, microform, manuscript or other formats of material whose subject areas would fall into these class designations. Bibliographies on individual psychologists, in the Z8000s, are also within the scope of this statement. Materials covering psychiatry are regarded as subsets of medicine, in various subclasses of R, since psychiatrists must first acquire M.D. degrees before specializing (see the Medicine Collections Policy Statement). Various topics outside the BF areas have psychological components and are classed within their own overall subject areas, e.g.: Religious Psychology (BL53 within Religion, BL); Educational Psychology (LB1051-1091 within Theory and Practice of Education, LB); Psychohistory (D16.16 within History [General], D); Psycholinguistics (P37 within Philology and Linguistics [General], P), Industrial Psychology (HF5548 within Business Administration, HF5001-6182). Works pertaining to the psychology of individual persons, ethnic groups, or classes of persons are cataloged within those overall subjects in the LC Classification scheme, but are given the topical subdivision “–Psychology” within the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) scheme; for example: “Abusive men—Psychology” (often HV6626 within Social Pathology, HV; or RC569.5.F3 within Neurology and psychiatry, RC321-571); “Actors—Psychology” (often PN2058 within Dramatic Representation: The Theater, PN2000-3307); “African Americans—Psychology” (E185.625 within History: American: African American, E184.5-185.98); or “Women—Psychology” (often HQ1206 within Women: Feminism, HQ1101-2030.7). -

1908 Journal

1 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 12, 1908. The court met pursuant to law. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham, Mr. Justice McKenna, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Day and Mr. Justice Moody. James A. Fowler of Knoxville, Tenn., Ethel M. Colford of Wash- ington, D. C., Florence A. Colford of Washington, D. C, Charles R. Hemenway of Honolulu, Hawaii, William S. Montgomery of Xew York City, Amos Van Etten of Kingston, N. Y., Robert H. Thompson of Jackson, Miss., William J. Danford of Los Angeles, Cal., Webster Ballinger of Washington, D. C., Oscar A. Trippet of Los Angeles, Cal., John A. Van Arsdale of Buffalo, N. Y., James J. Barbour of Chicago, 111., John Maxey Zane of Chicago, 111., Theodore F. Horstman of Cincinnati, Ohio, Thomas B. Jones of New York City, John W. Brady of Austin, Tex., W. A. Kincaid of Manila, P. I., George H. Whipple of San Francisco, Cal., Charles W. Stapleton of Mew York City, Horace N. Hawkins of Denver, Colo., and William L. Houston of Washington, D. C, were admitted to practice. The Chief Justice announced that all motions noticed for to-day would be heard to-morrow, and that the court would then commence the call of the docket, pursuant to the twenty-sixth rule. Adjourned until to-morrow at 12 o'clock. The day call for Tuesday, October 13, will be as follows: Nos. 92, 209 (and 210), 198, 206, 248 (and 249 and 250), 270 (and 271, 272, 273, 274 and 275), 182, 238 (and 239 and 240), 286 (and 287, 288, 289, 290, 291 and 292) and 167. -

About Half Way Through Proust

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2007). “The Best Form of Government…”: Cage’s Laissez-Faire Anarchism and Capitalism. The Open Space Magazine(8/9), pp. 91-115. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/5420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] “THE BEST FORM OF GOVERNMENT….”: CAGE’S LAISSEZ-FAIRE ANARCHISM AND CAPITALISM For Paul Obermayer, comrade and friend This article is an expanded version of a paper I gave at the conference ‘Hung up on the Number 64’ at the University of Huddersfield on 4th February 2006. My thanks to Gordon Downie, Richard Emsley, Harry Gilonis, Wieland Hoban, Martin Iddon, Paul Obermayer, Mic Spencer, Arnold Whittall and the editors of this journal for reading through the paper and subsequent article and giving many helpful comments. -

Claremen & Women in the Great War 1914-1918

Claremen & Women in The Great War 1914-1918 The following gives some of the Armies, Regiments and Corps that Claremen fought with in WW1, the battles and events they died in, those who became POW’s, those who had shell shock, some brothers who died, those shot at dawn, Clare politicians in WW1, Claremen courtmartialled, and the awards and medals won by Claremen and women. The people named below are those who partook in WW1 from Clare. They include those who died and those who survived. The names were mainly taken from the following records, books, websites and people: Peadar McNamara (PMcN), Keir McNamara, Tom Burnell’s Book ‘The Clare War Dead’ (TB), The In Flanders website, ‘The Men from North Clare’ Guss O’Halloran, findagrave website, ancestry.com, fold3.com, North Clare Soldiers in WW1 Website NCS, Joe O’Muircheartaigh, Brian Honan, Kilrush Men engaged in WW1 Website (KM), Dolores Murrihy, Eric Shaw, Claremen/Women who served in the Australian Imperial Forces during World War 1(AI), Claremen who served in the Canadian Forces in World War 1 (CI), British Army WWI Pension Records for Claremen in service. (Clare Library), Sharon Carberry, ‘Clare and the Great War’ by Joe Power, The Story of the RMF 1914-1918 by Martin Staunton, Booklet on Kilnasoolagh Church Newmarket on Fergus, Eddie Lough, Commonwealth War Grave Commission Burials in County Clare Graveyards (Clare Library), Mapping our Anzacs Website (MA), Kilkee Civic Trust KCT, Paddy Waldron, Daniel McCarthy’s Book ‘Ireland’s Banner County’ (DMC), The Clare Journal (CJ), The Saturday Record (SR), The Clare Champion, The Clare People, Charles E Glynn’s List of Kilrush Men in the Great War (C E Glynn), The nd 2 Munsters in France HS Jervis, The ‘History of the Royal Munster Fusiliers 1861 to 1922’ by Captain S. -

Filósofos O Viajeros: El Pensamiento Como Extravío

Astrolabio. Revista internacional de filosofía Año 2009. Núm. 8. ISSN 1699-7549. 16-32 pp. Towards a Reconciliation of Public and Private Autonomy in Thoreau’s ‘Hybrid’ Politics Antonio Casado da Rocha1 Resumen: Tras una revisión bibliográfica, el artículo proporciona una presentación de la filosofía política de Henry D. Thoreau, enfatizando en su obra un concepto de autodeterminación cívica que Habermas descompone en una autonomía pública y otra privada. Sostengo que Thoreau no era un anarquista antisocial, ni tampoco un mero liberal individualista, sino que su liberalismo presenta elementos propios de la teoría democrática e incluso del comunitarismo político. Finalmente, identifico y describo una tensión entre esos temas liberales y democráticos, tanto en la obra de Thoreau como en la vida política de las sociedades occidentales, mostrando así la relevancia de este autor. Palabras clave: Filosofía política, democracia, liberalismo, literatura norteamericana del siglo XIX Abstract: After a literature review, this paper provides an overview of Henry D. Thoreau’s political philosophy, with emphasis on the concept of civil self-determination, which Habermas sees as comprised of both private and public autonomy, and which is present in Thoreau’s own work. I argue that he was not an anti-social anarchist, or even a pure liberal individualist, but that along with the main liberal themes of his thought there is also a democratic, even communitarian strand. Finally, I identify and describe a tension between democratic and liberal themes in both his work and contemporary Western politics, thus highlighting Thoreau’s relevance. Key-words: Political philosophy, democracy, liberalism, 19th century North American literature According to Stanley Cavell (2005, pp. -

The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau's Political Thought

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Arcadian Exile: The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau’s Political Thought A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Politics School of Arts and Sciences of the Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Joshua James Bowman Washington, D.C. 2016 Arcadian Exile: The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau’s Political Thought Joshua James Bowman, Ph.D. Director: Claes G. Ryn, Ph.D. Henry David Thoreau‘s writings have achieved a unique status in the history of American literature. His ideas influenced the likes of Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., and play a significant role in American environmentalism. Despite this influence his larger political vision is often used for purposes he knew nothing about or could not have anticipated. The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze Thoreau’s work and legacy by elucidating a key tension within Thoreau's imagination. Instead of placing Thoreau in a pre-conceived category or worldview, the focus on imagination allows a more incisive reflection on moral and spiritual questions and makes possible a deeper investigation of Thoreau’s sense of reality. Drawing primarily on the work of Claes Ryn, imagination is here conceived as a form of consciousness that is creative and constitutive of our most basic sense of reality. The imagination both shapes and is shaped by will/desire and is capable of a broad and qualitatively diverse range of intuition which varies depending on one’s orientation of will. -

SPRING 2016 BANNER RECIPIENTS (Listed in Alphabetical Order by Last Name)

SPRING 2016 BANNER RECIPIENTS (Listed in Alphabetical Order by Last Name) Click on name to view biography. Render Crayton Page 2 John Downey Page 3 John Galvin Page 4 Jonathan S. Gibson Page 5 Irving T. Gumb Page 6 Thomas B. Hayward Page 7 R. G. Head Page 8 Landon Jones Page 9 Charles Keating, IV Page 10 Fred J. Lukomski Page 11 John McCants Page 12 Paul F. McCarthy Page 13 Andy Mills Page 14 J. Moorhouse Page 15 Harold “Nate” Murphy Page 16 Pete Oswald Page 17 John “Jimmy” Thach Page 18 Render Crayton_ ______________ Render Crayton Written by Kevin Vienna In early 1966, while flying a combat mission over North Vietnam, Captain Render Crayton’s A4E Skyhawk was struck by anti-aircraft fire. The plane suffered crippling damage, with a resulting fire and explosion. Unable to maintain flight, Captain Crayton ejected over enemy territory. What happened next, though, demonstrates his character and heroism. While enemy troops quickly closed on his position, a search and rescue helicopter with armed escort arrived to attempt a pick up. Despite repeated efforts to clear the area of hostile fire, they were unsuccessful, and fuel ran low. Aware of this, and despite the grave personal danger, Captain Crayton selflessly directed them to depart, leading to his inevitable capture by the enemy. So began seven years of captivity as a prisoner of war. During this period, Captain Crayton provided superb leadership and guidance to fellow prisoners at several POW locations. Under the most adverse conditions, he resisted his captor’s efforts to break him, and he helped others maintain their resistance.