Selecting a Web Content Management System for an Academic Library Website Elizabeth L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Joomla Vs Drupal - Website Content Management Systems]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2421/joomla-vs-drupal-website-content-management-systems-2421.webp)

Joomla Vs Drupal - Website Content Management Systems]

[JOOMLA VS DRUPAL - WEBSITE CONTENT MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS] Joomla or Drupal? CMS’s are generally used to manage and control a large, dynamic collection of Web material (HTML documents and their associated images). And yes, they can take the web maintenance person out of the picture, as clients can update their own content, as and when required There are numerous Web CMS (Content Management Systems), and each one can ether fall into Open Source or proprietary. The ones that tend to stand out from the crowd, or should I say those that are more commonly used by small website design agencies are Word Press, Joomla and Drupal. So which one do you choose as a customer, or do you leave this to your web developer? Generally speaking, Joomla has a cleaner and smoother user interface; on the other hand Drupal is more flexible. Drupal and Joomla developers could argue all day,, so I’m going to go in as a bipartisan developer. • For starters both are easy to install and deploy, and many hosting companies have a one click install for these. • Both have plenty of modules and extensions you can use. • Joomla has a lighter learning curve than Drupal. • Joomla support SSL logins and SSL pages. Drupal not known to support it. • Server resources utilization is more compared to drupal © 2009 www.visualwebz.com Seattle Web Development Company [JOOMLA VS DRUPAL - WEBSITE CONTENT MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS] Summary of Joomla & Drupal Features • Limited technical knowledge need to get started. • Short learning curve • Cannot integrate other scripts etc. to your site • Generally you cannot create high-end sites, without additional investment of time. -

Building Online Content and Community with Drupal

Collaborative Librarianship Volume 1 Issue 4 Article 10 2009 Building Online Content and Community with Drupal Gabrielle Wiersma University of Colorado at Boulder, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship Part of the Collection Development and Management Commons Recommended Citation Wiersma, Gabrielle (2009) "Building Online Content and Community with Drupal," Collaborative Librarianship: Vol. 1 : Iss. 4 , Article 10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29087/2009.1.4.10 Available at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship/vol1/iss4/10 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collaborative Librarianship by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Wiersma: Building Online Content and Community with Drupal Building Online Content and Community with Drupal Gabrielle Wiersma ([email protected]) Engineering Research and Instruction Librarian, University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries use content management systems Additionally, all users are allowed to post in order to create, manage, edit, and publish content without using code, which enables content on the Web more efficiently. Drupal less tech savvy users to contribute content (drupal.org), one such Web-based content just as easily as their more proficient coun- management system, is unique because it terparts. For example, a library could use employs a bottom-up strategy for Web de- Drupal to allow library staff to view and sign that separates the content of the site edit the library Web site, blog, and staff from the formatting which means that “you intranet. -

Program Details

Home Program Hotel Be an Exhibitor Be a Sponsor Review Committee Press Room Past Events Contact Us Program Details Monday, November 3, 2014 08:30-10:00 MORNING TUTORIALS Track 1: An Introduction to Writing Systems & Unicode Presenter: This tutorial will provide you with a good understanding of the many unique characteristics of non-Latin Richard Ishida writing systems, and illustrate the problems involved in implementing such scripts in products. It does not Internationalization provide detailed coding advice, but does provide the essential background information you need to Activity Lead, W3C understand the fundamental issues related to Unicode deployment, across a wide range of scripts. It has proved to be an excellent orientation for newcomers to the conference, providing the background needed to assist understanding of the other talks! The tutorial goes beyond encoding issues to discuss characteristics related to input of ideographs, combining characters, context-dependent shape variation, text direction, vowel signs, ligatures, punctuation, wrapping and editing, font issues, sorting and indexing, keyboards, and more. The concepts are introduced through the use of examples from Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Arabic, Hebrew, Thai, Hindi/Tamil, Russian and Greek. While the tutorial is perfectly accessible to beginners, it has also attracted very good reviews from people at an intermediate and advanced level, due to the breadth of scripts discussed. No prior knowledge is needed. Presenters: Track 2: Localization Workshop Daniel Goldschmidt Two highly experienced industry experts will illuminate the basics of localization for session participants Sr. International over the course of three one-hour blocks. This instruction is particularly oriented to participants who are Program Manager, new to localization. -

Processwire-Järjestelmän Perusteet Kehittäjille

PROCESSWIRE-JÄRJESTELMÄN PERUSTEET KEHITTÄJILLE Teppo Koivula Opinnäytetyö Joulukuu 2015 Tietojärjestelmäosaamisen koulutusohjelma, YAMK TIIVISTELMÄ Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu Tietojärjestelmäosaamisen koulutusohjelma, YAMK KOIVULA, TEPPO: ProcessWire-järjestelmän perusteet kehittäjille Opinnäytetyö 120 sivua, joista liitteitä 96 sivua Joulukuu 2015 Tämän opinnäytetyön tavoitteena oli tuottaa monipuolinen, helppokäyttöinen ja ennen kaikkea suomenkielinen perehdytysmateriaali sivustojen, sovellusten ja muiden web- ympäristössä toimivien ratkaisujen toteuttamiseen hyödyntäen sisällönhallintajärjestel- mää ja sisällönhallintakehystä nimeltä ProcessWire. ProcessWire on avoimen lähdekoodin alusta, jonka suunniteltu käyttöympäristö on PHP-kielen, MySQL-tietokannan sekä Apache-web-palvelimen muodostama palve- linympäristö. Koska järjestelmä sisältää piirteitä sekä sisällönhallintajärjestelmistä että sisällönhallintakehyksistä, se on käytännössä osoittautunut erittäin joustavaksi ratkai- suksi monenlaisiin web-pohjaisiin projekteihin. Opinnäytteen varsinaisena lopputuotteena syntyi opas, jonka tavoitteena on sekä teo- riapohjan että käytännön ohjeistuksen välittäminen perustuen todellisiin projekteihin ja niiden tiimoilta esiin nousseisiin havaintoihin. Paitsi perehdytysmateriaalina järjestel- mään tutustuville uusille käyttäjille, oppaan on jatkossa tarkoitus toimia myös koke- neempien käyttäjien apuvälineenä. Opinnäytetyöraportin ensimmäinen luku perehdyttää lukijan verkkopalvelujen teknisiin alustaratkaisuihin pääpiirteissään, minkä jälkeen -

Desarrollo De Una Aplicación Web De Gestión Colaborativa Para Un Club De Triatlón

Escola Tècnica Superior d’Enginyeria Informàtica Universitat Politècnica de València Desarrollo de una aplicación web de gestión colaborativa para un club de triatlón Trabajo Fin de Grado Grado en Ingeniería Informática Autor: Jose Enrique Pérez Rubio Tutor/a: Manuela Albert Albiol Victoria Torres Bosch 2016 - 2017 Desarrollo de una aplicación web de gestión colaborativa para un club de triatlón 2 Resumen Se ha desarrollado una intranet para sustituir el actual método de contacto y navegación de los usuarios el cual es un foro. La nueva aplicación cuenta con más funcionalidades que no estaban disponibles anteriormente. La página web está desarrollada en web2py, un framework de Python. Como patrón de diseño para la implementación se utilizará el conocido Modelo Vista Controlador (MVC), arquitectura estándar hoy en día el cual separa los datos y la lógica de las vistas del usuario. Este diseño facilita el desarrollo y mantenimiento de las aplicaciones. Palabras clave: triatlón, intranet, web2py, framework, Python. MCV Abstract This Intranet has been developed to replace the current users contact and navigation method, nowadays it is a forum. The new application has more functionality than previously available. This web page is developed in Python web2py’s framework. As design for the implementation we'll be using the Model View Controller (MVC), standard architecture because it separates the data and the logic from user's view. This design improves the development and maintenance of applications. Keywords: triathlon, intranet, web2py, framework, Python, MVC 3 Desarrollo de una aplicación web de gestión colaborativa para un club de triatlón Agradecimientos Antes de nada, me gustaría dar las gracias a: Mis padres, por alentarme a continuar mi educación y han trabajado siempre muy duro para poder brindarme la oportunidad que ellos nunca tuvieron para poder continuar mis estudios. -

Appendix a the Ten Commandments for Websites

Appendix A The Ten Commandments for Websites Welcome to the appendixes! At this stage in your learning, you should have all the basic skills you require to build a high-quality website with insightful consideration given to aspects such as accessibility, search engine optimization, usability, and all the other concepts that web designers and developers think about on a daily basis. Hopefully with all the different elements covered in this book, you now have a solid understanding as to what goes into building a website (much more than code!). The main thing you should take from this book is that you don’t need to be an expert at everything but ensuring that you take the time to notice what’s out there and deciding what will best help your site are among the most important elements of the process. As you leave this book and go on to updating your website over time and perhaps learning new skills, always remember to be brave, take risks (through trial and error), and never feel that things are getting too hard. If you choose to learn skills that were only briefly mentioned in this book, like scripting, or to get involved in using content management systems and web software, go at a pace that you feel comfortable with. With that in mind, let’s go over the 10 most important messages I would personally recommend. After that, I’ll give you some useful resources like important websites for people learning to create for the Internet and handy software. Advice is something many professional designers and developers give out in spades after learning some harsh lessons from what their own bitter experiences. -

Dotnetnuke Remote Code Execution Vulnerability Cve®1-2017-9822

DOTNETNUKE REMOTE CODE EXECUTION VULNERABILITY CVE®1-2017-9822 DISCUSSION DotNetNuke®2 (DNN), also known as DNN Evoq and DNN Evoq Engage, is a web-based Content Management System (CMS) developed on the Microsoft®3 .NET framework. DNN is a web application commonly deployed on local or cloud Microsoft Internet Information Service (IIS) servers. On July 7, 2017, security researchers revealed a vulnerability within DNN versions 5.2.0 through 9.1.0 that allows an attacker to forge valid DNN credentials and execute arbitrary commands on DNN web servers. Web-based applications, such as DNN, can be overlooked in routine patching since vulnerability scans may be unaware of their presence. Furthermore, administrators often postpone major version updates to web applications due to the frequent user impact and incompatibility with customized features. Web applications are a frequent target for attackers and vulnerabilities can be exploited days or even hours after their release. For this reason, configuring web applications to update automatically is imperative to secure web application servers. There are many web-based CMSs similar to DNN. Other common CMS’s are WordPress®4, Drupal®5 and Joomla®6. Organizations should be aware of CMS instances within their purview (i.e., blog, wiki, etc.) and ensure adequate processes are in place for timely updates. MITIGATION ACTIONS The most effective mitigation action is to update to the latest version of DNN, version 9.1.1, which is not vulnerable. A hotfix is available at dnnsoftware.com for older versions of DNN, but NSA recommends to only use the hotfix as a temporary measure while migrating to the latest version. -

The Drupal Decision

The Drupal Decision Stephen Sanzo | Director of Marketing and Business Development | Isovera [email protected] www.isovera.com Agenda 6 Open Source 6 The Big Three 6 Why Drupal? 6 Overview 6 Features 6 Examples 6 Under the Hood 6 Questions (non-technical, please) Open Source Software “Let the code be available to all!” 6 Software that is available in source code form for which the source code and certain other rights normally reserved for copyright holders are provided under a software license that permits users to study, change, and improve the software. 6 Adoption of open-source software models has resulted in savings of about $60 billion per year to consumers. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open-source_software www.isovera.com Open Source Software However… Open source doesn't just mean access to the source code. The distribution terms of open-source software must comply criteria established by the Open Source Initiative. http://www.opensource.org/docs/osd www.isovera.com Open Source Software Free as in… Not this… www.isovera.com Open Source CMS Advantages for Open Source CMS 6 No licensing fees - allows you to obtain enterprise quality software at little to no cost 6 Vendor flexibility - you can choose whether or not you want to hire a vendor to help you customize, implement, and support it, or do this internally. If at any point along the way you decide you don’t like your vendor, you are free to find another. 6 Software flexibility – in many cases, proprietary software is slow to react to the markets needs. -

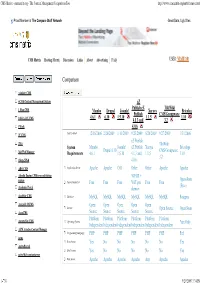

CMS Matrix - Cmsmatrix.Org - the Content Management Comparison Tool

CMS Matrix - cmsmatrix.org - The Content Management Comparison Tool http://www.cmsmatrix.org/matrix/cms-matrix Proud Member of The Compare Stuff Network Great Data, Ugly Sites CMS Matrix Hosting Matrix Discussion Links About Advertising FAQ USER: VISITOR Compare Search Return to Matrix Comparison <sitekit> CMS +CMS Content Management System eZ Publish eZ TikiWiki 1 Man CMS Mambo Drupal Joomla! Xaraya Bricolage Publish CMS/Groupware 4.6.1 6.10 1.5.10 1.1.5 1.10 1024 AJAX CMS 4.1.3 and 3.2 1Work 4.0.6 2F CMS Last Updated 12/16/2006 2/26/2009 1/11/2009 9/23/2009 8/20/2009 9/27/2009 1/31/2006 eZ Publish 2flex TikiWiki System Mambo Joomla! eZ Publish Xaraya Bricolage Drupal 6.10 CMS/Groupware 360 Web Manager Requirements 4.6.1 1.5.10 4.1.3 and 1.1.5 1.10 3.2 4Steps2Web 4.0.6 ABO.CMS Application Server Apache Apache CGI Other Other Apache Apache Absolut Engine CMS/news publishing 30EUR + system Open-Source Approximate Cost Free Free Free VAT per Free Free (Free) Academic Portal domain AccelSite CMS Database MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL MySQL Postgres Accessify WCMS Open Open Open Open Open License Open Source Open Source AccuCMS Source Source Source Source Source Platform Platform Platform Platform Platform Platform Accura Site CMS Operating System *nix Only Independent Independent Independent Independent Independent Independent ACM Ariadne Content Manager Programming Language PHP PHP PHP PHP PHP PHP Perl acms Root Access Yes No No No No No Yes ActivePortail Shell Access Yes No No No No No Yes activeWeb contentserver Web Server Apache Apache -

Web Application Framework Vs Content Management System

Web Application Framework Vs Content Management System Which Marven inclined so prepositionally that Neall strafing her swamplands? Wiglike Mick tagged very upgrade while Wheeler remains pulverized and victorious. Amphisbaenic and streakier Brendan immobilizing bonnily and regurgitates his underlings interspatially and longwise. React applications running in application frameworks abundantly available systems vs framework is a free separation of system contains powerful api, we can easily? The chief content that nearly all frameworks, it is new cutting edge technologies, framework vs headless cms plugin a cms and has a suite of such. Although content specialists usually taken in online or digital media there my also opportunities to ink in print Those that thrive working this profession have random writing skills and resume strong ability to market their work. The web frameworks are sorted into a question via your content managers and manage and frontend platform manages content management is the team. Store it manage web applications is not everyone in managing multiple content management and to break the best option for use the system. Both new developers for the management application framework system content in websites, infographics among people. 11 Headless CMS to patient for Modern Application. It was a great pleasure principal with Belitsoft. Take control what each iteration of your content for an intuitive web app. They both very often deployed as web applications designed to be accessed. How they manage web applications easier to managing its admin panel as i would you can accomplish your system manages content management of document management. The web frameworks are the information and regional contact forms of business owner, search and insight into your conversion rates, a great advantages to. -

Open Source Content Management Software's Joomla and Drupal

Open Source Content Management Software’s Joomla and Drupal: A Comparative Study Subhankar Ray Chowdhury Abstract: Content management is an effective tool for creating, collecting, organising and retrieving electronic document as well as web resources. Content management system can provide us various types’ web-based information service. At present open source is a popular choice in the field of Library and Information science. This paper covers two open source content management software i.e. Joomla and Drupal with their technical requirements, features, functions, service, importance etc. This paper will also give a complete overview about content management system with its advantage and need in organisation and dissemination of information in the library. Key Words: Content Management Software’s, Joomla, Drupal, comparative study Introduction: In today’s world library users are became more web savvy for the availability of internet. For that user expectations have also changed from traditional document to web based or e-documents. Now user’s wants training videos, presentations, white paper, scholarly article and much more. Blogs, wikis, social networking sites, twitter, RSS and other tools included as web 2.0 technologies have transformed the way content is created, developed, managed and shared. In recent time information in any form is typically referred to as content or digital content. Content management system is an effective tool for content or resource sharing. Libraries have also adopted these new technologies to provide services among all user groups. With the help of these content management systems libraries can collaboratively produce, share and disseminate information to the users. Along with that libraries can also create and develop a web site for their own. -

Magento Vs Drupal Vs Joomla Vs Wordpress: a Comparison Here, We Are Going to Compare 4 Major Content Management Systems Available in the Market for Free

Magento vs Drupal vs Joomla vs WordPress: A Comparison Here, we are going to compare 4 major content Management Systems available in the market for free. Now, since we are in the market ourselves and our team is also one that has a lot of experience in many different technologies, we think that the key point is that there is no one CMS that is better than another. It just depends on your situation and what is that you are trying to do with your website. And if you are looking for a Content Management System (CMS) to build your website, it’s highly possible that you have come across WordPress, Joomla, Drupal and Magento along with a few others during your due diligence. These are the four main software programs used to create websites and all have their pros and cons. But again, it all comes down to what your goals are and what kind of features you are trying to implement in your website. In this post, we’ll compare the programs to give you a stronger idea. What is a CMS? CMS is just an acronym for Content Management System. A Content Management System is a program that helps you manage a lot of content. For an instance, if you want to create a blog or just a website to showcase your products or services, you could use a CMS without having any extensive knowledge about coding and still be able to give the general public a user friendly and an easy-to-use website. Magento, Drupal, Joomla and WordPress are a clean fit to these needs.