Up in the Air: My Chuck Overby Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everything You Wanted to Know About Transgender Studies but Were Afraid to Ask Clara Reeve

humanities Article “More and More Fond of Reading”: Everything You Wanted to Know about Transgender Studies but Were Afraid to Ask Clara Reeve Desmond Huthwaite Faculty of English, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 1TN, UK; [email protected] Abstract: Clara Reeve’s (1729–1807) Gothic novel The Old English Baron is a node for contemplating two discursive exclusions. The novel, due to its own ambiguous status as a gendered “body”, has proven a difficult text for discourse on the Female Gothic to recognise. Subjected to a temperamental dialectic of reclamation and disavowal, The Old English Baron can be made to speak to the (often) subordinate position of Transgender Studies within the field of Queer Studies, another relationship predicated on the partial exclusion of undesirable elements. I treat the unlikely transness of Reeve’s body of text as an invitation to attempt a trans reading of the bodies within the text. Parallel to this, I de- velop an attachment genealogy of Queer and Transgender Studies that reconsiders essentialism—the kind both practiced by Female Gothic studies and also central to the logic of Reeve’s plot—as a fantasy that helps us distinguish where a trans reading can depart from a queer one, suggesting that the latter is methodologically limited by its own bad feelings towards the former. Keywords: Clara Reeve; Female Gothic; trans; queer; gender; embodiment The “literary offspring of the Castle of Otranto” had, and continues to have, something Citation: Huthwaite, Desmond. 2021. of a difficult birth.1 In its first year of life, the text was christened twice (titled The Champion “More and More Fond of Reading”: of Virtue in 1777, then Old English Baron in a revised 1778 edition); described alternately Everything You Wanted to Know as a transcription, a translation, a history, a romance, and (most enduringly) a “Gothic about Transgender Studies but Were story”; attributed to “the editor of the PHOENIX” and then to Clara Reeve; and subjected Afraid to Ask Clara Reeve. -

June 2009 Through Oct 2019 Approved Kentucky Production Industry Incentive Applicants/Incentives Awarded

June 2009 through Oct 2019 Approved Kentucky Production Industry Incentive Applicants/Incentives Awarded Maximum Project Overview Date of Maximum Tax Tax Credit Total Approved Tax Credit Date Credit Approved Company Approved Approval Credit Approved Status Expenditures Awarded Awarded Expenditures Feature film based upon the life of the Fast Track Films, Inc. 8/29/2009 $4,000,000 $800,000 4 thoroughbred Secretariat. Feature film based upon the life of the Fast Track Films, Inc. (Amended App) 10/13/2009 $7,000,000 $1,400,000 1 $6,137,990 $1,227,598 2/11/2011 thoroughbred Secretariat. Feature film based upon a fictional story taking place in south central Kentucky. Green Nation Entertainment, LLC 10/13/2009 $1,100,000 $220,000 2 Written, produced and directed by a Kentucky native now residing in California. Multi-state television commercial campaign Darling Advertising Agency, Inc. 4/7/2010 $208,016 $41,603 3 for Insight Communications. Episode of Extreme Makeover: Home Lock & Key Productions, LLC 10/14/2010 $857,593 $171,519 1 $695,473 $140,647 1/21/2011 Edition filmed in Fairdale. Feature length film indicating locations to Boo Partners, LLC 5/19/2011 $1,057,000 $211,400 4 be primarily in the Stanford area. Feature length film indicating locations to be primarily in the northern Kentucky area ADH Productions, Inc. 11/22/2011 $4,091,069 $1,047,767 4 between Covington and Louisville. Documentary on the history of Woodford Marvo Entertainment Group, LLC 2/28/2012 $90,000 $18,000 County and historically significant Woodford County natives. -

Twins in Contemporary Literature and Culture Also by Juliana De Nooy DERRIDA, KRISTEVA, and the DIVIDING LINE Twins in Contemporary Literature and Culture Look Twice

Twins in Contemporary Literature and Culture Also by Juliana de Nooy DERRIDA, KRISTEVA, AND THE DIVIDING LINE Twins in Contemporary Literature and Culture Look Twice Juliana de Nooy University of Queensland © Juliana de Nooy 2005 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2005 978-1-4039-4745-1 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-52433-4 ISBN 978-0-230-28686-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230286863 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Program Book Design Didi Tuttle " Conor Walsh Anita Szostak 2 3 SATUR DAY 3

join the con committee! game bids now being accepted! register now! www.interactiveliterature.org/E/ CONCOM NOTE FROM THE CONCHAIR Con Chair Outreach Team ThanksforcomingtoInterconD!HaveyouhadthismuchfunLARPingbefore?Ifso,we’vedoneourjob.Thisyear,Dstands Tim “Teem” Lasko Alex Bradley for Déjà Vu . Our previous conventions have had so many great LARPs that so many people wanted to play that by far the Anna Bradley biggestcommentwegetis“WhenwillXrunLARPYagain?”I’veaskedthatquestionmyselfmorethanonce.So,thisyear, New England Interactive weaskedGMswho’verunfantasticLARPsatpastconventionstoconsiderbringingthembackagainforanencoreatInterconD. Literature Board Hotel Liaison ButtherearealsoplentyofnewLARPsdebutinghereatInterconD!Andwe’resurethattheywillbereceivedwiththesame Chad Bergeron David Clarkson David Clarkson " enthusiasm. Intercon is not only about playing LARPs but also meeting other LARPers. This convention draws players and Jeff Diewald Cheryl Knoepler " LARPs from around the country and even Europe. There are representatives and information from several different LARP Tim “Teem” Lasko Vendor Liaison Chris Amherst groups,ongoingLARPcampaignsandotherconventionsthatyou’llwanttocheckout.We’rehavingbothaFridaynightand Treasurer SaturdaynightsocialeventthisyeartogiveyouthechancetocatchupwithyourfellowLARPersormeetthemforthefirst Michael McAfee T-Shirt & Artwork Design time.IfthisisyourfirstIntercon,orevenyourfirsttimeLARPing,Ihopeyouhavesomuchfunthatyou’llwanttotellyour Susan Giusto friends and bring them next year. Game Bid Chair & Schedule -

How Twin Peaks Changed the Face of Contemporary Television

“That Show You Like Might Be Coming Back in Style” 44 DOI: 10.1515/abcsj-2015-0003 “That Show You Like Might Be Coming Back in Style”: How Twin Peaks Changed the Face of Contemporary Television RALUCA MOLDOVAN Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca Abstract The present study revisits one of American television’s most famous and influential shows, Twin Peaks, which ran on ABC between 1990 and 1991. Its unique visual style, its haunting music, the idiosyncratic characters and the mix of mythical and supernatural elements made it the most talked-about TV series of the 1990s and generated numerous parodies and imitations. Twin Peaks was the brainchild of America’s probably least mainstream director, David Lynch, and Mark Frost, who was known to television audiences as one of the scriptwriters of the highly popular detective series Hill Street Blues. When Twin Peaks ended in 1991, the show’s severely diminished audience were left with one of most puzzling cliffhangers ever seen on television, but the announcement made by Lynch and Frost in October 2014, that the show would return with nine fresh episodes premiering on Showtime in 2016, quickly went viral and revived interest in Twin Peaks’ distinctive world. In what follows, I intend to discuss the reasons why Twin Peaks was considered a highly original work, well ahead of its time, and how much the show was indebted to the legacy of classic American film noir; finally, I advance a few speculations about the possible plotlines the series might explore upon its return to the small screen. Keywords: Twin Peaks, television series, film noir, David Lynch Introduction: the Lynchian universe In October 2014, director David Lynch and scriptwriter Mark Frost announced that Twin Peaks, the cult TV series they had created in 1990, would be returning to primetime television for a limited nine episode run 45 “That Show You Like Might Be Coming Back in Style” broadcast by the cable channel Showtime in 2016. -

Political Mythologies of the Mexican

DRUGLORDS, COWBOYS, DESPERADOES: POLITICAL MYTHOLOGIES OF THE MEXICAN-AMERICAN FRONTIER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Rafael Acosta Morales May, 2014 © 2014 Rafael Acosta Morales DRUGLORDS, COWBOYS, DESPERADOES: POLITICAL MYTHOLOGIES OF THE MEXICAN-AMERICAN FRONTIER Rafael Acosta Morales, Ph. D. Cornell University 2014 Cowboys, drug lords and desperadoes, with their unholstered guns, riding horses or trucks, roaming through the wide desert, represent key parts of the political mythology of the Mexican and American frontiers. This is a territory that, even as it has always been considered peripheral, has had a central role in shaping the central identities of both countries, as well as in the development of their attitudes towards violence and conflict, legality and illegality. My research focuses on these three figures and the territory in which they roam, eliciting from narratives that center around them theories of political exceptionality, legitimation, and substantiality. On the frontier regions of the liberal, representative state, its shortcomings become more obvious, and betray the blind spots of our political schema. I argue in my dissertation that the manifestations of violence that surround this territory do not arise in spite of the state and its notions of legality, but because of the law and the processes through which it comes into existence. To illustrate this point, I construct a narrative divided in three chapters, which develops the imaginary of each figure, focusing on the work of Cormac McCarthy, Clint Eastwood, Luis G. Inclán, Yuri Herrera, Américo Paredes and Rolando Hinojosa. -

“Isn't It Swell... Nowadays?”: the Reception History of Chicago On

“Isn’t It Swell . Nowadays?”: The Reception History of Chicago on Stage and Screen A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Michael M. Kennedy BM, Butler University, 2004 MM, University of Hartford, 2008 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, PhD Abstract The musical Chicago represents an anomaly in Broadway history: its 1996 revival far surpassed the modest success of the original 1975 production. Despite the original production’s box-office accomplishments, it received disparaging reviews regarding the cynicism of the work’s content. The musical celebrates the crimes and acquittals of two murderesses, and is based on Maurine Dallas Watkins’s coverage as a Chicago Tribune reporter of two 1924 murder cases, from which she generated a 1926 Broadway play. The 1975 Broadway production of Chicago: A Musical Vaudeville utilized this historical source material to comment on contemporary American society, highlighting parallels between the U.S. justice system and the entertainment industry, which critics and audiences of the post-Watergate era deemed as too cynical. Although Chicago initially achieved a mixed reception, the revival’s producers made few changes to John Kander’s music, Fred Ebb’s lyrics, and Ebb and Bob Fosse’s book, aside from simplifying the title to Chicago: The Musical. This suggests that the musical’s newfound success can be attributed to a societal shift in the perception of its subject matter. With further success from Chicago’s 2002 film adaptation, the originally dark and sardonic material became a smash hit and found itself as mainstream entertainment at the turn of the millennium. -

Female and Evil: the Role Gender Plays for Villains In

2013 University of Utrecht Faculty of the Humanities Author: Terry Guijt Student number: 3622045 Supervisor: Dr. R.H. Leurs Second reader: Dr. J.I.L. Veugen Date: 9-8-2013 [FEMALE AND EVIL: THE ROLE GENDER PLAYS FOR VILLAINS IN ADVENTURE GAMES] Keywords: Philosophy of Evil, Digital Games, Gender, Stereotypes, Feminism __________________________________________________________________________ This research paper examines how female evil is represented in adventure games from 1982 till 2013 and how this representation of female evil can be understood in a cultural philosophical perspective. First, the philosophical growth of the term evil is summarized and the paper describes how media forms, such as art, literature and movies, have represented evil in the past. While these art forms focus on representation through images, sound and text, video games introduce interactivity as a new tool to represent, understand and occasionally even be evil. Observed is that female villains are represented through text, images, sound and extra diegetic material. By examining the female gender role of end bosses in digital games, the portrayal of evil is studied and it is shown that humanlike female end bosses become demonized oral villains as their representation is stereotyped with the use of symbols for evil. Only when the villain is a genderless being the female aspects of the end boss can be said to be of cultural importance. Dear reader, While the King needs to be put checkmate, it is the defeat of the Queen that causes the most relief --- Playing a game of Chess This thesis is written to conclude the master’s degree Media and Performance Studies at the University of Utrecht. -

Sex, Power, and Sedition in Margaret Atwood's Writing

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-8-2020 Iron Manicures: Sex, Power, and Sedition in Margaret Atwood's Writing Anna Zarra Aldrich [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Zarra Aldrich, Anna, "Iron Manicures: Sex, Power, and Sedition in Margaret Atwood's Writing" (2020). Honors Scholar Theses. 729. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/729 Iron Manicures: Sex, Power, and Sedition in Margaret Atwood's Writing Anna Zarra Aldrich Thesis Advisor: Regina Barreca, Ph.D. Honors Advisor: Mary Burke, Ph.D. 1 Abstract Margaret Atwood has often been criticized as a bad feminist writer for featuring villainous, cruel women. Atwood has combatted this criticism by pointing out that evil women exist in life, so they should in literature as well. Every story requires a villain and a victim, for Atwood these roles are both usually played by women. This thesis will explore the idea of the woman as spectacle in both behavior and body. Women are controlled by the idea that they must care. When they stop caring, they become a threat. At the heart of Atwood’s writing are the relationships between women both bitter and powerful. This thesis examines the relationships through which women control other women, as well as the destabilizing power of female alliances. -

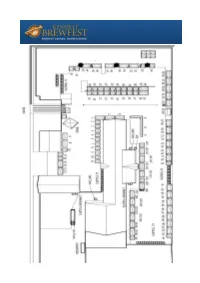

Brewfest-Map.Pdf

Brewery Location Magic Hat 111 Allagash 32 Manayunk 19 Anchor 118 McKenzie's Brewhouse 7 Arcadia 61 McKenzie's Cider/ Omission/ Redbridge/ Stella Cidre 107 Argilla brewing Co. 75 MOA 103 Ballast Point 62 Mission 47 Barren Hill 3 Naked Brewing Co 45 Bells Brewery 82 Neshaminy Creek Brewing Co 63 Blue Moon(Tenth and Blake) 33 Old Dominion 116 Boulder 16 Old Forge Brewing Co 48 Boxcar 117 Ommegang 12 Brewer's Alley 80 Otter Creek 98 Brewer's Art 17 Penn Brewing 87 Brooklyn Brewing 92 Philadelphia Brewing 40 Bullfrog 57 Pilsner Urquell?Peroni 96 Clown Shoes 59 Pizza Boy brewing 6 Coronado 70 Prism beer Co. 109 Darkhorse 69 Redhook/Widmer/Kona 105 Deschutes 84 Rogue 101 Dock Street 38 Round Guys Brewing 9 Dogfish Head 20 Sam Adams 21 DuClaw 60 Saranac 37 Evil Genius Brewing 8 Saucony Creek Brewing Co 83 Evil Twin 54 Shawnee Craft Brewing 90 Evolution Craft Brewing 115 Shiner 31 Fegley Brew Works 81 Shocktop 108 Finch's 114 Sierra Nevada 23 Firestone Walker 28 Sixpoint 30 Fishtale 43 Sly Fox 14 Flying Fish 89 Spire Mountain Cider/Leavenworth 41 Forest and Main Brewing 11 Sprecher 64 Four (4) Hands 58 St Boniface 76 Free Will Brewing 77 St Killian Imports 100 Full Sail 113 Starr Hill 119 Fullers/ Bass/ Boddingtons 112 Stillwater 51 Goose Island 110 Stone Brewing 13 Great Divide 88 Stoudt's 4 Great Lakes 24 Susquehanna Brewing 104 Guinness/Smithwicks 35 Swashbuckler Brewing 78 Half Acre/ Cigar City 71 Thomas Creek Brewery 42 Harpoon 26 Three Heads Brewing 44 Hofbrau/ Warsteiner 85 Troegs 5 House of Shandy/ Angry Orchard( Curious traveler) 21 Twin Lakes 18 In Bev Stella, Hoegaarden. -

Chapter 1 Chapter 2

Notes Chapter 1 1. I have analysed part of this series (texts by Ovid, Freud and Lacan) in an earlier article (de Nooy, 1991b). 2. I take ‘topos’ to refer not simply to a topic (such as twins) but to its embedding in a particular thematic arrangement or ‘place’ – conjoined twins, twins as sexual rivals, good and evil twins, the author and his twin/double, the incestu- ous twin couple, twins in enemy camps, twins separated at birth – which will tend to coincide with its occurrence in a particular genre. 3. The notion of retelling is not intended to imply that at some point of origin there exists a master-story, which is then reproduced in the form of versions of the original. Rather than assuming a hierarchy between renditions, I follow Barbara Herrnstein-Smith in understanding all stories as particular retellings, ‘constructed by someone in particular, on some occasion, for some purpose’ (1981: 167). Thus telling always involves some retelling, some gesture towards existing stories, and retelling entails both repetition and difference. 4. Rank’s ‘Der Doppelgänger’ was first published in 1914 and substantially revised in 1925. English (1971) and French (1973) translations exist. I shall refer to both on occasion, as the work translated in the French volume includes additional chapters, one of which is devoted to twinship (cf. the publication history detailed in Rank, 1971: vii–ix). 5. The relative coherence of the Romantic literature of the double – or at least of the established canon of works representing it – makes it possible to conceive of The Theme of The Double during this period: a singular theme of a paradoxically singular double. -

Stern Illinois University the Keep

Eastern Illinois University The Keep February 1986 2-14-1986 Daily Eastern News: February 14, 1986 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1986_feb Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: February 14, 1986" (1986). February. 9. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1986_feb/9 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1986 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Daily / •..w ill be cloudy with a 60 percent chance of snow, high in the ·20's. Northest winds are 1 O to 20 mph. Friday night, decreasmg cloudiness. stern with a low in the 20's. Saturday, partly ews sunny and warmer. CAA debates proposal on missing class By BILL DENNIS Staff writer Students who miss 25 percent of their class meetings by midterm could be involuntarily dropped from those courses if a policy proposed Thursday to the Council on Academic Affairs is passed. Sam Taber, dean of student academic services, proposed a change in Eastern's attendance policy which would give instructors the ability to drop a student from a course if that student has missed 25 percent of all classes held by midterm. Kandy Baumgardner, acting CAA chairman, said the policy could be voted on within the next two weeks. However, she predicted that, due to a full agenda, it might not be discussed until the Feb. 27 CAA meetirig. If passed, the new policy will go into effect in the fall -semester of 1986.