Notes on Shippo: a Sequel to Japanese Enamels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIFT GUIDE 2020 Hand-Crafted Treasures by Local Artists Holidaygift GUIDE 2020

HolidayGIFT GUIDE 2020 Hand-crafted treasures by local artists HolidayGIFT GUIDE 2020 Hand-crafted treasures by local artists Welcome to the first TAS Holiday Gift Guide 2020-curated by Talmadge Art Show producers, Sharon Gorevitz and Alan Greenberg. Shop with Talmadge Art Show artists virtually—anytime, anywhere! CONTACT THE ARTISTS DIRECTLY FOR ORDERS BY CLICKING ON A PRODUCT PHOTO, THEIR WEBSITE OR EMAIL LINKS. Be on the lookout for special emails about the TAS Holiday Questions? 619-559-9082 or [email protected] Gift Guide 2020 with information on specials, artists and crafts. Please enjoy this unique TAS Holiday Gift Guide 2020, however, it’s only live until December 31st. Happy Holidays… Sharon & Alan Holiday Gift Guide Table OF Contents JEWELRY 4-20 CERAMICS 21-27 MIXED MEDIA/FINE ART 28-30 WEARABLES 31-35 MATERIALS - WOOD, TILES, GLASS, METAL, FIBER, PAPER 36-41 PHOTOGRAPHY 42-43 Hand-crafted treasures by local artists Questions? 619-559-9082 or [email protected] TAS HOLIDAY GIFT GUIDE 2020 JEWELRY | 4 ARTIST BIO Organic Jewelry by Allie have been in business since 2010and our mission is to create jewels with a good karma. Our jewelry is nature sourced and nature inspired and sometimes denounces with art and/or enviromental issues. Our processes are Alessandra Thornton characteristic of slow fashion, and leave minimal carbon foot print in the environment. LOCATION CONTACT INFO TEMECULA, CA Organic Jewelry by Allie /OrganicJewelrybyAllie MEDIUM organicjewelrybyallie.com | 858.449.6801 /alessandrathornton/ Tagua nut, rainforest seeds, leather and other organic mediums [email protected] /OrganicjewelrybyAlli Paw Necklace Set Marine Life Jewelry Set Tiger Necklaces This is a 3 piece set and Our beautiful ocean animals Beautiful Animal, tiger print includes paw bracelet for featured in our hand carved handpainted tagua nuts pet mom, dog tag for the tagua nuts bracelets and necklaces are part of my pet and paw necklace for earrings deserve clean new “Cougar” or “Tigresa” the pet father. -

DIY Statement Necklace Making Ideas You'll Love

PRESENTS How to Make Necklaces: DIY Statement Necklace Making Ideas You’ll Love HOW TO MAKE NECKLACES: DIY STATEMENT NECKLACE MAKING IDEAS YOU’LL LOVE 7 DISCO DARLING Making the most of disc beads BY KEIRSTEN GILES 3 10 CHINESE WRITING MOKUME GANE STONE PENDANT HEART PENDANT Set an irregular stone Combine alternative metals with with pickets conventional materials BY LEXI ERICKSON BY ROGER HALAS NECKLACES COME IN ALL SHAPES AND SIZES, which is advantage of metal’s malleability to create a 3D heart one of the great things about them if you like developing pendant with mokumé gané, a layered metal whose your own jewelry designs. You can make other types of patterns stretch and compress as you form the heart jewelry in different styles from ancient to Edwardian to (create your own mokumé as shown with sterling, bronze, punk, too – you just have more ground to work with if and traditional alloys or buy sheet as metal stock), and you’re creating jewelry that’s worn around the neck. add a wink of sparkle with a small faceted gem. Or you can create your own pattern as you put together an Pendants are perfect for showing off interesting patterns impressive necklace using turquoise and wood button because you have enough room to show the whole pattern, beads linked together with copper wire and jump rings for a but pendants work just as well for something small, simple, and contemporary look on a traditional form. uniform. Like pendant necklaces, necklaces without a focal or with a focal area made of multiple elements can be as big or Start your next necklace making venture with these varied little as you or your customers like. -

Annual Report 2009

Bi-Annual 2009 - 2011 REPORT R MUSEUM OF ART UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA CELEBRATING 20 YEARS Director’s Message With the celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Harn Museum of Art in 2010 we had many occasions to reflect on the remarkable growth of the institution in this relatively short period 1 Director’s Message 16 Financials of time. The building expanded in 2005 with the addition of the 18,000 square foot Mary Ann Harn Cofrin Pavilion and has grown once again with the March 2012 opening of the David A. 2 2009 - 2010 Highlighted Acquisitions 18 Support Cofrin Asian Art Wing. The staff has grown from 25 in 1990 to more than 50, of whom 35 are full time. In 2010, the total number of visitors to the museum reached more than one million. 4 2010 - 2011 Highlighted Acquisitions 30 2009 - 2010 Acquisitions Programs for university audiences and the wider community have expanded dramatically, including an internship program, which is a national model and the ever-popular Museum 6 Exhibitions and Corresponding Programs 48 2010 - 2011 Acquisitions Nights program that brings thousands of students and other visitors to the museum each year. Contents 12 Additional Programs 75 People at the Harn Of particular note, the size of the collections doubled from around 3,000 when the museum opened in 1990 to over 7,300 objects by 2010. The years covered by this report saw a burst 14 UF Partnerships of activity in donations and purchases of works of art in all of the museum’s core collecting areas—African, Asian, modern and contemporary art and photography. -

Ancient Skills, New Worlds Twenty Treasures of Japanese Metalwork from a Private Collection New York I September 12, 2018

Ancient Skills, New Worlds Twenty Treasures of Japanese Metalwork from a Private Collection New York I September 12, 2018 Ancient Skills, New Worlds Twenty Treasures of Japanese Metalwork from a Private Collection Wednesday September 12, 2018 at 10am New York BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Japanese Art Department Monday – Friday 9am-5pm New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Jeffrey Olson, Director +1 (212) 644 9001 bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6516 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax [email protected] PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit ILLUSTRATIONS www.bonhams.com/25151 Takako O’Grady, Thursday September 6 Front cover: Lot 10 Administrator 10am to 5pm Back Cover: Lot 2 Friday September 7 Please note that bids should be +1 (212) 461 6523 summited no later than 24hrs [email protected] 10am to 5pm REGISTRATION prior to the sale. New bidders Saturday September 8 IMPORTANT NOTICE 10am to 5pm must also provide proof of Joe Earle Please note that all customers, Sunday September 9 identity when submitting bids. Senior Consultant irrespective of any previous activity 10am to 5pm Failure to do this may result in +44 7880 313351 with Bonhams, are required to Monday September 10 your bid not being processed. [email protected] complete the Bidder Registration 10am to 5pm Form in advance of the sale. The form Tuesday September 11 LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS can be found at the back of every 10am to 3pm AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE catalogue and on our website at Please email bids.us@bonhams. -

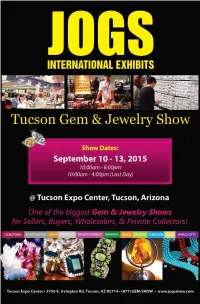

JOGS Show Guide F2015

2 | JOGS SHOW JOGS SHOW | 3 4 | JOGS SHOW TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION: PAGE: Show Floorplan ...................................................................................... 5 Show Terms & Policies ......................................................................... 6 List of Exhibitors ................................................................................... 12 JOGS SHOW | 5 6 | JOGS SHOW JOGS SHOW | 7 LET’S PROMOTE AMBER TOGETHER SHARE WITH US YOUR STORY! SO MANY EXHIBITIONS! SO MANY STANDS! HOW CAN A BUYER SEE YOU? BE VISIBLE! BE WITH THE BALTIC JEWELLERY NEWS! “Baltic Jewellery News” / Paplaujos str. 5–7, LT-11342 Vilnius, Lithuania / Tel./Fax +370 5 212 08 23 / E-mail: [email protected] 8 | JOGS SHOW www.balticjewellerynews.com JOGS SHOW | 9 10 | JOGS SHOW TUCSON JOGS SHOW SPECIAL %50 OFF IN TRADITIONAL SS RINGS JOGS SHOW | 11 List of Exhibitors 1645 JEWELRY 1645 W Ohio St Booth#: W422 Chicago, IL 60622 Custom Turkish jewelry, semiprecious USA stones with brass. Tel: 872-212-9950 ABSOLUTE JEWELRY MFG 4400 N Scottsdale Rd, #9205 Booth#: W615, W617, W516, W518 Scottsdale, AZ 85257 Sterling silver, handmade inlay jewelry. USA Tel: (480) 437-0411 AF DESIGN INC 1212 Broadway Booth#: W715, W717 NY, NY 10001 Manufacturer and Designer of Silver, USA Stainless Steel, Fashion, Marcasite Tel: 212 683 2559 Jewelry with Gemstones http://afdesigninc.com/ AFRICA GEMS USA 10 Muirfield Blvd. Booth#: W605, W607 Monroe TWP, NJ 8831 Semi-precious stone beads, rough USA stones. Tel: 732 572 6670 AMBERMAN 650 S Hill St, Ste 513 Booth#: W408, W410 Los Angeles, CA 90014 Amber jewelry set in sterling silver, USA beads, cameos. Tel: (213) 629-2112 www.amberman.com ANNA KING JEWELRY 112 Kimball Rd Booth#: W407 Ridge, NH 3461 Semi-precious stones and carvings from USA around the world as well as unusual Tel: 603-852-3375 items such as Russian hand painting www.annakingjewelry.com porcelain, glass, crystal and other catalyst items. -

Name, a Novel

NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubu editions 2004 Name, A Novel Toadex Hobogrammathon Cover Ilustration: “Psycles”, Excerpts from The Bikeriders, Danny Lyon' book about the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club. Printed in Aspen 4: The McLuhan Issue. Thefull text can be accessed in UbuWeb’s Aspen archive: ubu.com/aspen. /ubueditions ubu.com Series Editor: Brian Kim Stefans ©2004 /ubueditions NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubueditions 2004 name, a novel toadex hobogrammathon ade Foreskin stepped off the plank. The smell of turbid waters struck him, as though fro afar, and he thought of Spain, medallions, and cork. How long had it been, sussing reader, since J he had been in Spain with all those corkoid Spanish medallions, granted him by Generalissimo Hieronimo Susstro? Thirty, thirty-three years? Or maybe eighty-seven? Anyhow, as he slipped a whip clap down, he thought he might greet REVERSE BLOOD NUT 1, if only he could clear a wasp. And the plank was homely. After greeting a flock of fried antlers at the shevroad tuesday plied canticle massacre with a flash of blessed venom, he had been inter- viewed, but briefly, by the skinny wench of a woman. But now he was in Rio, fresh of a plank and trying to catch some asscheeks before heading on to Remorse. I first came in the twilight of the Soviet. Swigging some muck, and lampreys, like a bad dram in a Soviet plezhvadya dish, licking an anagram off my hands so the ——— woundn’t foust a stiff trinket up me. So that the Soviets would find out. -

There Is a Silver Lining. Kaki D

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2003 There is a Silver Lining. Kaki D. Crowell-Hilde East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Crowell-Hilde, Kaki D., "There is a Silver Lining." (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 784. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/784 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. There Is A Silver Lining A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Art and Design East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts by Kaki D. Crowell-Hilde August 2003 David G. Logan, Committee Chair Carol LeBaron, Committee Member Don R. Davis, Committee Member Keywords: Metalsmithing, Casting, Alloys, Etching, Electroforming, Raising, Crunch-raising, Patinas, Solvent Dyes ABSTRACT There Is A Silver Lining by Kaki D. Crowell-Hide I investigated two unique processes developed throughout this body of work. The first technique is the cracking and lifting of an electroformed layer from a core vessel form. The second process, that I named “crunch-raising”, is used to form vessels. General data were gathered through research of traditional metalsmithing processes. Using an individualized approach, new data were gathered through extensive experimentation to develop a knowledge base because specific reference information does not currently exist. -

Reliable Irogane Alloys and Niiro Patination—Further Study Of

Reliable irogane alloys and niiro patination—further study of production and application to jewelry JONES, Alan Hywel and O'DUBHGHAILL, Coilin Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/4331/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version JONES, Alan Hywel and O'DUBHGHAILL, Coilin (2010). Reliable irogane alloys and niiro patination—further study of production and application to jewelry. In: Santa Fe Symposium on Jewelry Manufacturing Technology 2010: proceedings of the twenty- fourth Santa Fe Symposium in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Albuquerque, N.M., Met- Chem Research, 253-286. Repository use policy Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in SHURA to facilitate their private study or for non- commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Jones Reliable Irogane Alloys and Niiro Patination—Further Study of Production and Application to Jewelry Jones Dr. A. H. Jones Principal Researcher, Materials and Engineering Research Institute Dr. Cóilín Ó Dubhghaill Jones Senior Research Fellow, Art and Design Research Centre Sheffield Hallam University Sheffield, UK Jones Abstract Japanese metalworkers use a wide range of irogane alloys (shakudo, shibuichi), which are colored with a single patination solution (niiro eki). -

Precious Metal Products Catalogue

CHAFNER@ Precious Metal • Technology Precious Metal Products General catalogue c-hafner.de/en Table of contents C.HAFNER page 04 High-quality precious metal products page 06 Certified security page 07 Semi-finished parts - Stock range page 08 Stock range (Semi-finished parts and solders, brazing pastes) page 10 Efficient soldering page 14 Equipment page 15 Creative semi-finished parts and semi-finished products page 16 Fibre mats page 18 Fibre sheets page 19 Layer sheets page 20 Layer tubes page 20 Strip gold page 21 Mokume gane page 22 Mokume gane blocks page 23 Mokume gane sheets page 24 Silver clay page 25 Ring blanks page 26 Loops page 28 Loops - bracelets and huggies page 29 Services in the field of precious metals page 30 Precious Metal Recycling page 32 Precious Metal Trading page 34 environmental C.HAFNER High-quality precious metal products As a leading manufacturer of precious metal products, C.HAFNER offers a full range of high-quality materials and semi-finished products. This includes casting materials, sheets, wires, tubes, solders and brazing pastes, as well as our unique range of creative semi-finishedproducts. Wealways have a broad range of products available fromstock forunique and small series manufacturers. Customised solutions. For industry and craftsmen. Platin Gold In addition to the distribution of standard products, The innovative platinum alloy PlatinGold by C.HAFNER C.HAFNER sees itself as a provider of customised so has rewritten the history of platinum: Platingold sets new lutions for processing precious metals. These include, standards with its unprecedented and fascinating com for example, modern CNC/EM technologies. -

Fine Japanese Art J J AUCTION Fine Japanese Art

Fine Japanese Art J J AUCTION Fine Japanese Art Saturday, June 2nd 2018 at 4pm CET CATALOG JAP0618 VIEWING www.zacke.at IN OUR GALLERY May 21st - June 1st Monday - Friday 10am - 6pm June 2nd 10am - 2pm and by appointment GALERIE ZACKE MARIAHILFERSTRASSE 112 1070 VIENNA AUSTRIA Tel +43 1 532 04 52 Fax +20 E-mail offi[email protected] 1 IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABSENTEE BIDDING FORM (According to the general terms and conditions of business Gallery Zacke Vienna) FOR THE AUCTION FINE JAPANESE ART JAP0618 ON DATE Saturday, June 2ND, 2018 at 4 pm CET NO. TITLE BID IN EURO PLEASE RAISE MY PURCHASE BID BY ONE PLEASE CALL ME IF THERE IS ALREADY A HIGHER WRITTEN BID BID STEP (APPROX. 10%) IF NECESSARY TEL Notice: All bids are to be understood plus buyer`s premium (incl. VAT). If you like to bid by telephone please write in the column purchase limit „ TEL” . A bid by telephone shall automatically represent a bid at the starting price for this item. If Galerie Zacke cannot reach the Client during the auction, Galerie Zacke will bid up to the starting price for him. If no one else bids on the corresponding good, then the Client shall automatically receive the winning bid at the starting price. TERMS OF PAYMENT, SHIPPING AND COLLECTION: NAME EMAIL With the signature on this form the client declares his consent to aforementioned commissioning of Galerie Zacke. Bids by telephone shall be governed by the AGB (terms and conditions) of Galerie Zacke. The AGB of Galerie Zacke are part of the commissioning of Galerie Zacke by the client. -

Saint Louis Art Fair 2019 Juror Scorecard

ZAPP - Custom Report 4/1/19, 1'53 PM JUROR EVENT JURYING LOGGED IN AS LERICKC Logout Main Jury Menu 1. Jury 2. > Scorecard Saint Louis Art Fair 2019 Juror Scorecard Application: 1 of 551 ID#: 1761005 Statement: Contemporary, unique jewelry primarily comprised of gold vermeil and sterling silver. Each piece of jewelry explores a varied range of shapes, sizes and textures. Sheets of metal are manipulated using various techniques such as sanding, forging and hammering to create satin and pummeled finishes. Discipline: Three - Dimensional Work Score: Yes No Maybe Comments: Pod Pendant Lola Earrings Sterling silver ribbon Grace Cuff 2019 Booth 1" x 2" x .5" .5" x 1.5" x 3mm earrings 1" x 3.5" x 3mm 1" x 1.25" x .5" Save Score Application: 2 of 551 ID#: 1761009 Statement: Fabricated from re purposed silver plate trays from thrift stores. The material is always a new challenge because the base metal may be brass, copper, or a mystery. The metal is treated with a heat patina from a torch with sometimes surprising results. Deconstructed, wabi- sabi, never predictable. Discipline: Three - Dimensional Work Score: Yes No Maybe Comments: Brooch Two Bangles Two Pendants Chain Necklace booth 3" x 3" 4" x 4" x .25" 1.50" x 3" x .25" 18" x 2" https://admin.zapplication.org/admin/dir_jury/app_view.php?nonce=5…c0a773f865d&limit=9999&limitvalue=0&discipline=104551&limit=100000 Page 1 of 221 ZAPP - Custom Report 4/1/19, 1'53 PM Save Score Application: 3 of 551 ID#: 1761023 Statement: I lift textures from seeds, pods and buds. -

Van Cleef & Arpels

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto April 29 – August 6, 2017 Organized by The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto Nikkei Inc. The Kyoto Shimbun Supported by the Embassy of France / Institut français du Japon With special cooperation from Van Cleef & Arpels • The numbers correspond to the catalogue, though the objects may not necessarily be displayed in the same order. • Some objects may be rotated during the exhibition period (First term April 29 - June 18; Second term June 20 - August 6). Display may change as circumstances require. • The temperature, humidity and brightness of the exhibition rooms are strictly controlled under international standards for preservation reasons. We apologize for any inconvenience this may cause. Jewelry * Unless otherwise noted, works of jewelry are from the Van Cleef & Arpels Collection. Section 1: History of Van Cleef & Arpels No. title date material and technique ownership Italy, circa 1 Marie-Madeleine brooch, Gold, glass, micromosaic 1860–1870 2 Model of the Varuna yacht, circa 1907 Gold, silver, jasper, wood, enamel 3 Watch pendant necklace 1912 Platinum, enamel, pearls, diamonds 4 Nice meeting of aviation cigarette case 1922 Gold, sapphires 5 Envelope powder case circa 1922 Gold, enamel 6 Earrings 1923 Platinum, sapphires, diamonds 7 Pampilles earrings 1923 Platinum, emeralds, diamonds 8 Chinese inspired lapel watch 1924 Platinum, gold, enamel, pearl, diamonds 9 Sarpech brooch 1924 Platinum, emeralds, sapphires, rubies, diamonds 10 Art Deco bracelet 1925 Platinum, diamonds 11 Flowers basket