Unfortunately, a Number of Leases Are Missing, but of Those Extant the First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Practice Newsletter Edition 9 – Summer 2019

Practice Newsletter Edition 9 – Summer 2019 Inside this Edition Page 2. Team News Page 3. Access to Appointments Page 4. E-Consult – the introduction of on-line consultations Page 5. Primary Care Networks. Public Meeting – Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital Page 6. Practice News and Events. There are 2 important changes at the practice which are both happening on 1st July We will be switching on E-Consult on July 1st which will provide our patients with the facility to consult with our GPs via an on-line consultation. This is a truly significant development in the way we interact with our patients and you can find out more about it on page 4 of this newsletter. On the same day we will be changing our booking process for same-day appointments so that these will only be available via the phone from 8:30 am. This means that you will not be able to book an appointment by queuing up at the reception desk when we open. The practice has issued an information sheet for patients which explains why we have had to make this change. It is on our website and can be viewed via the QR code. Copies are also available at the Reception Desk. We hope you enjoy our newsletter and find it informative. We look forward to hearing your feedback. Visit our new website at www.ainsdalemedicalcentre.nhs.uk And follow us on social media as @ainsdaledocs Ainsdale Medical Centre Newsletter – Summer 2019 Page 1 | 6 Team News Dr Richard Wood will be retiring from the Partnership at the end of July. -

Of Its Integrated Coastal Zone Management The

Sustainable Development and Planning II, Vol. 1 475 The ‘Sefton Coast Partnership’: an overview of its integrated coastal zone management A. T. Worsley1, G. Lymbery2, C. A. Booth3, P. Wisse2 & V. J. C. Holden1 1Natural, Geographical and Applied Sciences, Edge Hill University, Ormskirk, Lancashire, U.K. 2Coastal Defence Unit, Ainsdale Discovery Centre Complex, Southport, Merseyside, U.K. 3Environmental and Analytical Sciences Division, Research Institute in Advanced Technologies (RIATec), The University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, West Midlands, U.K. Abstract The Sefton Coast Partnership (SCP), based in Sefton, Merseyside, UK, is set within the context of and reported as an example of Integrated Coastal Zone Management. It has developed out of a well-established and successful Management Scheme and, since its inception, attempted with varying success to develop a ‘working partnership’ which has sustainable management at its heart and which is responsible for conservation and the needs of the local community. The history, function and structure of the SCP are described together with the problems that emerged as the partnership developed. Keywords: ICZM, partnership, sustainable management, Sefton. 1 Introduction The coastal zone is hugely significant in terms of sustainable management since this is where human activities affect and are inseparable from marine and terrestrial processes and environments both in developed countries and the Third World. Integrated management therefore requires a holistic, geographic approach and, in order to be successful, action at the local and regional level which is supported by the national government. This paper introduces the Sefton Coast Partnership as an example of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) in WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, Vol 84, © 2005 WIT Press www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3541 (on-line) 476 Sustainable Development and Planning II, Vol. -

Operator Address Seaforth Radio Cars Incorporating One Call 105

Operator Address Seaforth Radio Cars Incorporating One Call 105 Bridge Road Liverpool Merseyside L21 2PB L & N Travel 233 Meols Cop Road Southport Merseyside PR8 6JU Delta Merseyside Ltd 200 Strand Road Bootle Merseyside L20 3HL Cyllenius Airport Travel Services 100 Derby Road Unit 1501 Bootle L20 1BP Glenn Travel AIRPORTTRANSFERS247.COM LTD Suite 12 39A Sefton Lane Industrial Estate Maghull L31 8BX Prince Executive Cars Letusgetyouthere 8 Fenton Close Bootle Merseyside L30 1TE GoingtotheAirport.co.uk 12 Bridge Road Liverpool Merseyside L23 6SG Cavalier Travel 73 Bridge Road Liverpool Merseyside L21 2PA Phoenix Cars 17a Elbow Lane Formby Merseyside L37 4AB Dixons Direct Central Cars Southport 161 Eastbank Street, Southport Merseyside PR8 6TH All White Taxis 181-183 Eastbank Street Southport Merseyside PR8 6TH Steve's Shuttle Service Blueline 50 Private Hire 54/56 Station Road, Liverpool Merseyside L31 3DB Taylor Made Tours of Liverpool Ltd 2 Village Courts Liverpool Merseyside L30 7RE Formby Village Radio Cars 36C Chapel Lane, Liverpool Merseyside L37 4DU Phil's Airport Transport David Bragg R & R Airport Transfer Specialist 12 Wineva Gardens Liverpool Merseyside L23 9SJ Travel 2000 62 Bedford Road Southport Merseyside PR8 4HJ Anytime Travel 38 Trevor Drive Liverpool Merseyside L23 2RW Liverpool VIP Travel 23 Truro Avenue Netherton Bootle Merseyside L30 5QR A.P.L Executive Travel 1 Lower Alt Road Liverpool Merseyside L38 0BA PJ Chauffeur Services 43 Chesterfield Road Liverpool Merseyside L23 9XL A & S Travel 11a Oakwood Avenue Southport Merseyside PR8 3HX Ennis David T/A Upgrade Travel ( sole trader ) Airport Distance Local 38 Larkfield Lane Southport Merseyside PR9 8NW Acorn Cars Maghull Business Centre Liverpool Merseyside L31 2HB Aintree Lane Travel 104 Aintree Lane Liverpool Merseyside L10 2JW Kwik Cars (North West) Ltd 3 St Lukes Road Southport Merseyside PR9 0SH Johns Travel Nicholson Mullis Ltd. -

TOGETHER Our Churches Have Been Closed As Directed by Archbishop Malcolm

Newsletter for Catholics in Birkdale 29 March 2020 + Fifth Sunday in Lent + Sundays Year A + Weekdays Year 2 TOGETHER Our churches have been closed as directed by Archbishop Malcolm. For now your homes are a domestic church. I was delighted to see that Claudia has taken matters into her own hands and gathered her family for prayer! Masses Intentions 29 March—5 April Sat Col. Michael John Bennetts A Sunday Parishioners Mon Stephen Buckley Tues John Ormsby A Wed John Wade LD Thurs Fr Patrick O’Sullivan Fri Margaret Parr and Towers Family Sat Thomas and Margaret Kennedy A Palm Sunday Parishioners How Do I Make a Spiritual Communion? Alone or together with others in your household Make the sign of the cross You could read the Gospel of the day Then share prayer intentions quietly or aloud Say the Lord’s Prayer Then make an act of spiritual communion At home we can follow Mass online, Make a Spiritual My Jesus, Communion, Pray for those who are ill, the dying, NHS staff I believe that You are present who care for them, for one another. in the Most Holy Sacrament. Let’s not get lonely! Stay in touch using the telephone 568313 I love You above all things, and I desire to receive You into my soul. or email [email protected], or join our Facebook Since I cannot at this moment page: Birkdale Catholics. Please share with family and friends. receive You sacramentally, At this time we can only send out the newsletter TOGETHER come at least spiritually into my heart. -

Walking & Cycling Newsletter

Sefton’s Spring Walking & Cycling Newsletter Issue 43 / April – June 2017 Spring has sprung, time to join one of our great walks or rides throughout Sefton. Contents Walking Cycling Walking Diary 3 Cycling Diary 23 Monday 4 Pedal Away 24 Maghull Health Walks Southport Hesketh Centre 25 Netherton Feelgood Factory Health Walks Ride Programme Macmillan Rides 25 Crosby Health Walks Tour de Friends 26 St Leonard’s Health Walks The Chain Gang Ainsdale Health Walks Rides for the over 50’s 27 Tuesday 6 Sefton Circular Cycle Ride 28 Bootle Health Walks Dr Bike – Free Bicycle Maintenance 29 Hesketh Park Health Walks Tyred Rides 30 Walking Diary Formby Pinewoods Health Walks Ditch the Stabilisers 30 Box Tree Health Walks Active Walks is Sefton’s The walks range from 10 to 30 minutes Waterloo Health Walks Wheels for All 31 up to 90 minutes for the Walking for Wednesday 8 Freewheeling 31 local health walk Health walks and 90 to 150 minutes for Wednesday Social Health Walks programme and offers walks beyond Walking for Health. Netherton Health Walks a significant number Walking is the perfect exercise as it places Sefton Trailblazers Introduction little stress upon bones and joints but uses Thursday 10 Now the clocks have sprung forwards of regular walking groups over 200 muscles within the body and can we can enjoy lighter, brighter days May Logan Health Walks across Sefton. The walks help develop and maintain fitness. Formby Pool Health Walks and spend more time outdoors Ainsdale Sands Health Walks walking and cycling around Sefton continue throughout Prambles and beyond. -

Complete List of Roads in Sefton ROAD

Sefton MBC Department of Built Environment IPI Complete list of roads in Sefton ROAD ALDERDALE AVENUE AINSDALE DARESBURY AVENUE AINSDALE ARDEN CLOSE AINSDALE DELAMERE ROAD AINSDALE ARLINGTON CLOSE AINSDALE DORSET AVENUE AINSDALE BARFORD CLOSE AINSDALE DUNES CLOSE AINSDALE BARRINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE DUNLOP AVENUE AINSDALE BELVEDERE ROAD AINSDALE EASEDALE DRIVE AINSDALE BERWICK AVENUE AINSDALE ELDONS CROFT AINSDALE BLENHEIM ROAD AINSDALE ETTINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE BOSWORTH DRIVE AINSDALE FAIRFIELD ROAD AINSDALE BOWNESS AVENUE AINSDALE FAULKNER CLOSE AINSDALE BRADSHAWS LANE AINSDALE FRAILEY CLOSE AINSDALE BRIAR ROAD AINSDALE FURNESS CLOSE AINSDALE BRIDGEND DRIVE AINSDALE GLENEAGLES DRIVE AINSDALE BRINKLOW CLOSE AINSDALE GRAFTON DRIVE AINSDALE BROADWAY CLOSE AINSDALE GREEN WALK AINSDALE BROOKDALE AINSDALE GREENFORD ROAD AINSDALE BURNLEY AVENUE AINSDALE GREYFRIARS ROAD AINSDALE BURNLEY ROAD AINSDALE HALIFAX ROAD AINSDALE CANTLOW FOLD AINSDALE HARBURY AVENUE AINSDALE CARLTON ROAD AINSDALE HAREWOOD AVENUE AINSDALE CHANDLEY CLOSE AINSDALE HARVINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE CHARTWELL ROAD AINSDALE HATFIELD ROAD AINSDALE CHATSWORTH ROAD AINSDALE HEATHER CLOSE AINSDALE CHERRY ROAD AINSDALE HILLSVIEW ROAD AINSDALE CHESTERFIELD CLOSE AINSDALE KENDAL WAY AINSDALE CHESTERFIELD ROAD AINSDALE KENILWORTH ROAD AINSDALE CHILTERN ROAD AINSDALE KESWICK CLOSE AINSDALE CHIPPING AVENUE AINSDALE KETTERING ROAD AINSDALE COASTAL ROAD AINSDALE KINGS MEADOW AINSDALE CORNWALL WAY AINSDALE KINGSBURY CLOSE AINSDALE DANEWAY AINSDALE KNOWLE AVENUE AINSDALE 11 May 2015 Page 1 of 49 -

Planning Committee Cabinet Council Date of Meeting

Committee: Planning Committee Cabinet Council Date of Meeting: 4th May 2011 26 th May 2011 7th July 2011 Title of Report: Birkdale Village Conservation Area Appraisal Report of: Alan Lunt, Director of Built Environment Contact Officer: Dorothy Bradwell Telephone 0151 934 3574 Yes No This report contains Confidential information ü Exempt information by virtue of paragraph(s) ……… of Part 1 ü of Schedule 12A to the Local Government Act 1972 ü Is the decision on this report DELEGATED? Purpose of Report: To seek Committee’s, Cabinet’s and Council’s approval of the contents of the Birkdale Village Conservation Areas Appraisal and agreement to adopt the proposed amendments to the Conservation Area’s boundaries (Appendix 1). Recommendation(s): That Planning Committee: (i) Recommend to Cabinet that the Birkdale Village Conservation Area Appraisal be adopted as a material consideration in the determination of planning applications. (ii) Recommend to Cabinet that they approve the proposed amendments to the Conservation Area’s boundaries shown on the plan appended That Cabinet: (i) Recommends that Council adopts the Birkdale Village Conservation Area Appraisal as a material consideration in the determination of planning applications. (ii) Recommends that Council approves the proposed amendments to the Conservation Area’s boundaries shown on the plan appended, under Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. That Council (i) Approves the proposed amendments to the Conservation Area’s boundaries shown on the plan appended, under Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. (ii) Approves the proposed amendments to the Conservation Area’s boundaries shown on the plan appended, under Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. -

Walking and Cycling Guide to Sefton’S Natural Coast

Walking and Cycling Guide to Sefton’s Natural Coast www.seftonsnaturalcoast.com Altcar Dunes introduction This FREE guide has been published to encourage you to get out and about in Southport and Sefton. It has been compiled to help you to discover Sefton’s fascinating history and wonderful flora and fauna. Walking or cycling through Sefton will also help to improve your health and fitness. With its wide range of accommodation to suit all budgets, Southport makes a very convenient base. So make the most of your visit; stay over one or two nights and take in some of the easy, family-friendly walks, detailed in this guide. Why not ‘warm-up’ by walking along Lord Street with its shops and cafés and then head for the promenade and gardens alongside the Marine Lake. Or take in the sea air with a stroll along the boardwalk of Southport Pier before walking along the sea wall of Marine Drive to the Queen’s Jubilee Nature Trail or the new Eco Centre nearby. All the trails and walks are clearly signposted and suitable for all ages and abilities. However, as with all outdoor activities, please take sensible precautions against our unpredictable weather and pack waterproof clothing and wear suitable shoes. Don’t forget your sun cream during the Summer months. If cycling, make sure that your bike is properly maintained and wear a protective helmet at all times. It's also a good idea to include some food and drink in a small day-pack, as although re-fuelling stops are suggested on the listed routes, there is no guarantee that they will be open when you need them. -

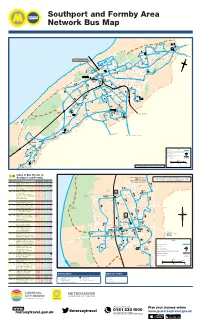

To Bus Routes in Southport and Formby

Southport and Formby Area Network Bus Map E M I V R A D R I N M E E A E N U I R N R E Harrogate Way A S V 40 M H A S Y O 40 A R D I W TRU S X2 to Preston D G R K H L I E I P E V A T M N R E O D 40 A R O C N 44 I R N L O O LSWI OAD O L A C R G K T Y E A V N A A E R . S D A E E RO ’ T K X2 G S N N R TA 40 E S 40 h RS t GA 44 A a W p O D B t A o P A R Fo I Y A 47.49 D V 40 l E ta C as 44 E Co n 44 fto 40 44 F Y L D E F e D S 15 40 R O A A I G R L Crossens W H E AT R O A D 40 A N ER V P X2 D M ROAD A D O THA E L NE H 15 Y R A O L N K A D E 347 W D O A S T R R 2 E ROA R O 347 K E D O . L A 47 E F Marshside R R D T LD 2 Y FIE 2 to Preston S H A ELL 49 A 15 SH o D D 347 to Chorley u W E N t V E I R 40 W R h R I N O M D A E p A L O o R F A r N F R t 15 R N E F N Golf O P I E S T O R A D X2 U A U H L ie 44 E N R M D N I F E R r Course E S LARK Golf V 347 T E D I C Southport Town Centre Marine D A E D N S H P U R A N E O E D A B Lake A Course I R R O A E 47 calls - N S V T R C 15.15 .40.44.46.46 .47.49.315(some)X2 R K V A E A E T N S HM E K R Ocean D I 2 E O M A L O O R A R L R R R IL O P Plaza P L H H B D A D O OO D E C AD A A R D 40 O A W 40 A S U 40 O N R T K 40 EE O 40 H R Y Y D L R E C LE F T L E S E E H U V W W L 15 O N I 49 KN Y R A R R G O D E R M O A L L S A R A A D M O E L M T E M I D B A Southport C R IDG E A E B Hesketh R S M I A N T C R S Hospital O E E E A Princes E 2 D E D R .1 P A A 5. -

Waterloo Road the Abbeyfield Promise: We Make Time So You Can Enjoy Life

Southport Waterloo Road The Abbeyfield Promise: We make time so you can enjoy life Making time for our residents is at the heart of everything we do. This promise means we have the time to share friendships, understand individual needs and make every day more fulfilling – so everyone feels valued, content, cared for and safe. Welcome to Waterloo Road Situated on a bustling, affluent road between Southport and Formby, our Abbeyfield house is located in the heart of the Birkdale area. At Abbeyfield we offer a home from home experience and our staff are crucial to creating this homely, friendly and welcoming environment. Delicious, daily home-cooked meals and communal area housekeeping are organised and all your household bills are included in the cost, leaving you free to enjoy your time. If you choose to live with us, you’ll enjoy your own comfortable room, socialising in shared lounges and dining areas, and a beautiful garden to relax in. Happiness starts with you We believe in enjoying later life and an Abbeyfield house will always offer you the opportunity to get involved in activities and entertainment – which is a big part of life in our houses. At Waterloo Road, we organise regular activities based on our residents wishes, whether it be a games afternoon or an outing to the town centre. Your safety and quality assurance You can’t enjoy peace of mind without trust. This is why our Abbeyfield house is registered and regulated by Homes England. But our quality control doesn’t end there – the opinions of our residents matter too. -

Background Information for Candidates

Background Information for Candidates Primary Care Networks From July 2019, NHS England made funding available for Primary Care Networks, through the national GP contract, for the creation of 7.5 Link Workers (FTE) who will work across the 7 Primary Care Networks in Sefton. A Primary Care Network (PCN) consist of groups of general practices working together with a range of local providers, including across primary care, community services, social care and the voluntary sector to offer more personalised, coordinated health and social care to their local population. Each PCN serves a patient population of between 30 and 50k. There are 7 PCN’s in Sefton. These are Bootle, Seaforth and Litherland, Crosby and Maghull, Formby, Ainsdale and Birkdale, Central Southport and North Southport. Primary Care Networks are an integral part of the recently published NHS Long-Term Plan which introduces this new role of social prescribing link workers into their multi-disciplinary teams as part of the expansion to the primary care workforce. This is an opportunity to work collaboratively with these developing PCN’s to establish this new role and shape social prescribing in Sefton. Social Prescribing Link Workers In December and January Sefton CVS recruited 7.5 FTE Social Prescribing Link Workers on behalf of host organisations, to support the delivery of a social prescribing service for Primary Care Networks in Sefton as part of the award winning Living Well Sefton programme. The social prescribing link workers are employed by a range of partner organisations working across the borough but function as one social prescribing team alongside Living Well Mentors in the wider service. -

Translocating Isle of Man Cabbage Coincya Monensis Ssp

Conservation Evidence (2012) 9, 67-71 www.conservationevidence.com Translocating Isle of Man cabbage Coincya monensis ssp. monensis in the sand-dunes of the Sefton coast, Merseyside, UK Philip H. Smith1* & Patricia A. Lockwood2 19 Hayward Court, Watchyard Lane, Formby, Liverpool L37 3QP 213 Stanley Road, Formby, Liverpool L37 7AN *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY This paper describes the results of a translocation rescue of the British endemic Isle of Man cabbage Coincya monensis ssp. monensis from a sand-dune ridge at Crosby, Merseyside, which was about to be excavated as a source of sand for a coastal protection scheme at nearby Hightown. Using methods developed during a 1992 translocation, over eight hundred 1st year plants, together with seed-pods, were moved by volunteers to two protected receptor sites at Crosby and Birkdale in August 2011. Monitoring the following summer located small surviving populations at the receptor sites but mortality of transplants appeared to be over 90%, seed germination and establishment contributing most individuals. Low success at Crosby seemed partly attributable to winter sand-blow and heavy public pressure, while vegetation overgrowth may have been an adverse factor at Birkdale. An unexpected finding was that the original Crosby colony survived the removal of most of its habitat, about 1300 plants being counted in 2012 on the levelled dune area. More than half were small seedlings, presumably derived from buried seed. Also, 234 Isle of Man cabbage plants were discovered on the new coastal defence bund at Hightown, having arisen from propagules transported from Crosby. Other known Sefton duneland colonies at Southport Marine Lake and Blundellsands were also monitored, the former having apparently declined to extinction.