Of Its Integrated Coastal Zone Management The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Practice Newsletter Edition 9 – Summer 2019

Practice Newsletter Edition 9 – Summer 2019 Inside this Edition Page 2. Team News Page 3. Access to Appointments Page 4. E-Consult – the introduction of on-line consultations Page 5. Primary Care Networks. Public Meeting – Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital Page 6. Practice News and Events. There are 2 important changes at the practice which are both happening on 1st July We will be switching on E-Consult on July 1st which will provide our patients with the facility to consult with our GPs via an on-line consultation. This is a truly significant development in the way we interact with our patients and you can find out more about it on page 4 of this newsletter. On the same day we will be changing our booking process for same-day appointments so that these will only be available via the phone from 8:30 am. This means that you will not be able to book an appointment by queuing up at the reception desk when we open. The practice has issued an information sheet for patients which explains why we have had to make this change. It is on our website and can be viewed via the QR code. Copies are also available at the Reception Desk. We hope you enjoy our newsletter and find it informative. We look forward to hearing your feedback. Visit our new website at www.ainsdalemedicalcentre.nhs.uk And follow us on social media as @ainsdaledocs Ainsdale Medical Centre Newsletter – Summer 2019 Page 1 | 6 Team News Dr Richard Wood will be retiring from the Partnership at the end of July. -

Community Engagement Plan Southport Town Deal

Community Engagement Plan Southport Town Deal June 2020 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Town Deals 2 3. Engagement Plan and Programme 5 4. Next steps 11 Appendix 1: Towns Fund Prospectus 1 1. Introduction 1.1 This Community Engagement Plan has been produced to support the emerging Southport Town Investment Plan. Its purpose is to outline the key engagement activities that have been undertaken to date with stakeholders, including elected members and representatives of the local community, and to detail the planned engagement and consultation prior to finalisation of the Southport Town Investment Plan. 1.2 This document is structured to provide: • An introduction to Town Deals and Town Investment Plans • Details of the engagement activities carried out to date and the proposed Engagement Plan and Programme • The proposed next steps 1.3 This Community Engagement Plan has been informed by information set out in the ‘Towns Fund Prospectus’ published by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) in November 2019. The Prospectus is included as Appendix 1 to this document. 1.4 The Community Engagement Plan has been produced by Turley on behalf of Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council (SMBC). It will be published by SMBC to ensure transparency over the engagement process to inform preparation of the Southport Town Investment Plan. 1 2. Town Deals 2.1 In November 2019 the Local Government Secretary invited 101 towns, including Southport, to develop proposals for a Town Deal with the Government, each one potentially receiving up to £25 million investment from the national £3.6 billion Towns Fund. 2.2 While Government has entered into a number of ‘City Deals’ to stimulate growth in large urban areas, smaller towns have been overlooked by that process and not always benefitted from economic growth even where located in close proximity to more prosperous areas. -

Framework Users (Clients)

TC622 – NORTH WEST CONSTRUCTION HUB MEDIUM VALUE FRAMEWORK (2019 to 2023) Framework Users (Clients) Prospective Framework users are as follows: Local Authorities - Cheshire - Cheshire East Council - Cheshire West and Chester Council - Halton Borough Council - Warrington Borough Council; Cumbria - Allerdale Borough Council - Copeland Borough Council - Barrow in Furness Borough Council - Carlisle City Council - Cumbria County Council - Eden District Council - South Lakeland District Council; Greater Manchester - Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council - Bury Metropolitan Borough Council - Manchester City Council – Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council - Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council - Salford City Council – Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council - Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council - Trafford Metropolitan Borough - Wigan Metropolitan Borough Council; Lancashire - Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council – Blackpool Borough Council - Burnley Borough Council - Chorley Borough Council - Fylde Borough Council – Hyndburn Borough Council - Lancashire County Council - Lancaster City Council - Pendle Borough Council – Preston City Council - Ribble Valley Borough Council - Rossendale Borough Council - South Ribble Borough Council - West Lancashire Borough Council - Wyre Borough Council; Merseyside - Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council - Liverpool City Council - Sefton Council - St Helens Metropolitan Borough Council - Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council; Police Authorities - Cumbria Police Authority - Lancashire Police Authority - Merseyside -

Annex F –List of Consultees

ANNEX F –LIST OF CONSULTEES Local highway authorities Leicester City Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Leicestershire County Council Bath & NE Somerset Council Lincolnshire County Council Bedfordshire County Council Liverpool City Council Birmingham City Council Local Government Association Blackburn & Darwen London Borough of Barking & Dagenham Blackpool Borough Council London Borough of Barnet Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Bexley Borough of Poole London Borough of Brent Bournemouth Borough Council London Borough of Bromley Bracknell Forest Borough Council London Borough of Camden Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Croydon Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Bristol City Council London Borough of Enfield Buckinghamshire County Council London Borough of Greenwich Bury Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Cambridgeshire County Council Fulham Cheshire County Council London Borough of Haringey City of York Council London Borough of Harrow Cornwall County Council London Borough of Havering Corporation of London London Borough of Hillingdon County of Herefordshire District Council London Borough of Hounslow Coventry City Council London Borough of Islington Cumbria County Council London Borough of Lambeth Cumbria Highways London Borough of Lewisham Darlington Borough Council London Borough of Merton Derby City Council London Borough of Newham Derbyshire County Council London -

Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council

Annex A SEFTON METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL GAMBLING ACT 2005 STATEMENT OF GAMBLING LICENSING POLICY Draft V.2 SEFTON METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL – STATEMENT OF GAMBLING LICENSING POLICY CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 General Statement 2.0 Scope • Premises Licence • Permits • Provisional Statements • Temporary Use Notices • Occasional Use Notices • Small Lotteries 3.0 Gambling Licensing Objectives 4.0 Casino Licences 5.0 The Licensing Process • Interested Parties • Responsible Authorities • Delegation of decisions and functions • Hearings • Review of licences 6.0 Licensing Conditions • Mandatory conditions • Default conditions • Door Supervisors 7.0 Information Protocols 8.0 Enforcement Protocols ANNEXES The following annexes do not form part of the approved Statement of Gambling Licensing Policy but are included to assist applicants in meeting the requirements of the licensing process. Annex 1 - Map of Sefton Annex 2 - Responsible Authorities Annex 3 - Gaming Machine Definition Tables 1 SEFTON METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL – STATEMENT OF GAMBLING LICENSING POLICY 1.0 GENERAL STATEMENT 1.1 Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council (the Council) is the Licensing Authority (the Authority), under the Gambling Act 2005 (the Act), responsible for granting Premises Licences, issuing certain Permits and Provisional Statements, receiving and endorsing Temporary Use Notices, receiving Occasional Use Notices and registering Small Lotteries under the Act. 1.2 Section 349 of the Act requires that all Licensing Authorities prepare and publish a statement of the principles that they propose to apply in exercising their functions under the Act during the period to which the policy applies. 1.3 In carrying out its licensing functions the Authority will promote the Gambling Licensing Objectives which are: • Preventing gambling from being a source of crime or disorder, being associated with crime or disorder or being used to support crime; • Ensuring that gambling is conducted in a fair and open way; and • Protecting children and other vulnerable persons from being harmed or exploited by gambling. -

Walking & Cycling Newsletter

Sefton’s Spring Walking & Cycling Newsletter Issue 43 / April – June 2017 Spring has sprung, time to join one of our great walks or rides throughout Sefton. Contents Walking Cycling Walking Diary 3 Cycling Diary 23 Monday 4 Pedal Away 24 Maghull Health Walks Southport Hesketh Centre 25 Netherton Feelgood Factory Health Walks Ride Programme Macmillan Rides 25 Crosby Health Walks Tour de Friends 26 St Leonard’s Health Walks The Chain Gang Ainsdale Health Walks Rides for the over 50’s 27 Tuesday 6 Sefton Circular Cycle Ride 28 Bootle Health Walks Dr Bike – Free Bicycle Maintenance 29 Hesketh Park Health Walks Tyred Rides 30 Walking Diary Formby Pinewoods Health Walks Ditch the Stabilisers 30 Box Tree Health Walks Active Walks is Sefton’s The walks range from 10 to 30 minutes Waterloo Health Walks Wheels for All 31 up to 90 minutes for the Walking for Wednesday 8 Freewheeling 31 local health walk Health walks and 90 to 150 minutes for Wednesday Social Health Walks programme and offers walks beyond Walking for Health. Netherton Health Walks a significant number Walking is the perfect exercise as it places Sefton Trailblazers Introduction little stress upon bones and joints but uses Thursday 10 Now the clocks have sprung forwards of regular walking groups over 200 muscles within the body and can we can enjoy lighter, brighter days May Logan Health Walks across Sefton. The walks help develop and maintain fitness. Formby Pool Health Walks and spend more time outdoors Ainsdale Sands Health Walks walking and cycling around Sefton continue throughout Prambles and beyond. -

Complete List of Roads in Sefton ROAD

Sefton MBC Department of Built Environment IPI Complete list of roads in Sefton ROAD ALDERDALE AVENUE AINSDALE DARESBURY AVENUE AINSDALE ARDEN CLOSE AINSDALE DELAMERE ROAD AINSDALE ARLINGTON CLOSE AINSDALE DORSET AVENUE AINSDALE BARFORD CLOSE AINSDALE DUNES CLOSE AINSDALE BARRINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE DUNLOP AVENUE AINSDALE BELVEDERE ROAD AINSDALE EASEDALE DRIVE AINSDALE BERWICK AVENUE AINSDALE ELDONS CROFT AINSDALE BLENHEIM ROAD AINSDALE ETTINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE BOSWORTH DRIVE AINSDALE FAIRFIELD ROAD AINSDALE BOWNESS AVENUE AINSDALE FAULKNER CLOSE AINSDALE BRADSHAWS LANE AINSDALE FRAILEY CLOSE AINSDALE BRIAR ROAD AINSDALE FURNESS CLOSE AINSDALE BRIDGEND DRIVE AINSDALE GLENEAGLES DRIVE AINSDALE BRINKLOW CLOSE AINSDALE GRAFTON DRIVE AINSDALE BROADWAY CLOSE AINSDALE GREEN WALK AINSDALE BROOKDALE AINSDALE GREENFORD ROAD AINSDALE BURNLEY AVENUE AINSDALE GREYFRIARS ROAD AINSDALE BURNLEY ROAD AINSDALE HALIFAX ROAD AINSDALE CANTLOW FOLD AINSDALE HARBURY AVENUE AINSDALE CARLTON ROAD AINSDALE HAREWOOD AVENUE AINSDALE CHANDLEY CLOSE AINSDALE HARVINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE CHARTWELL ROAD AINSDALE HATFIELD ROAD AINSDALE CHATSWORTH ROAD AINSDALE HEATHER CLOSE AINSDALE CHERRY ROAD AINSDALE HILLSVIEW ROAD AINSDALE CHESTERFIELD CLOSE AINSDALE KENDAL WAY AINSDALE CHESTERFIELD ROAD AINSDALE KENILWORTH ROAD AINSDALE CHILTERN ROAD AINSDALE KESWICK CLOSE AINSDALE CHIPPING AVENUE AINSDALE KETTERING ROAD AINSDALE COASTAL ROAD AINSDALE KINGS MEADOW AINSDALE CORNWALL WAY AINSDALE KINGSBURY CLOSE AINSDALE DANEWAY AINSDALE KNOWLE AVENUE AINSDALE 11 May 2015 Page 1 of 49 -

Downloadable Claim Form

ex_44396_pd00530_sefton_benefit_claim_form_insert_V2_Insert 19/03/2013 12:24 Page 1 Sefton Council Notes for filling in your claim form About this form This Housing Benefit and Council Tax Reduction claim form has been specially designed to be easy to fill in. It may look rather long, but we have to ask a lot of questions to make sure that you get the right amount of benefit. You may not have to fill in all parts of the form, but you must fill in any part that is relevant to you. Every part starts with a question to help you decide if you need to fill in that part. Write in black ink. Do not write in pencil. If you make a mistake, just cross it out and put the right answer next to it. Do not use correction fluid or tape. Answer ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ questions by putting a tick in the relevant box. If you are picking an answer from a list of answers, put a tick in the box next to your answer. Do not put a cross in any boxes. If you answer a question with a cross we will have to send the form back to you, and this will delay your claim. If someone else fills in the form for you, there is a space for them to sign so we know the form was filled in for you. If you need help filling in the form If you need any help, phone 0845 140 0845. If you have problems hearing, our textphone number is 0151 934 4327. -

Walking and Cycling Guide to Sefton’S Natural Coast

Walking and Cycling Guide to Sefton’s Natural Coast www.seftonsnaturalcoast.com Altcar Dunes introduction This FREE guide has been published to encourage you to get out and about in Southport and Sefton. It has been compiled to help you to discover Sefton’s fascinating history and wonderful flora and fauna. Walking or cycling through Sefton will also help to improve your health and fitness. With its wide range of accommodation to suit all budgets, Southport makes a very convenient base. So make the most of your visit; stay over one or two nights and take in some of the easy, family-friendly walks, detailed in this guide. Why not ‘warm-up’ by walking along Lord Street with its shops and cafés and then head for the promenade and gardens alongside the Marine Lake. Or take in the sea air with a stroll along the boardwalk of Southport Pier before walking along the sea wall of Marine Drive to the Queen’s Jubilee Nature Trail or the new Eco Centre nearby. All the trails and walks are clearly signposted and suitable for all ages and abilities. However, as with all outdoor activities, please take sensible precautions against our unpredictable weather and pack waterproof clothing and wear suitable shoes. Don’t forget your sun cream during the Summer months. If cycling, make sure that your bike is properly maintained and wear a protective helmet at all times. It's also a good idea to include some food and drink in a small day-pack, as although re-fuelling stops are suggested on the listed routes, there is no guarantee that they will be open when you need them. -

To Bus Routes in Southport and Formby

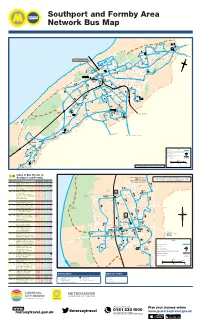

Southport and Formby Area Network Bus Map E M I V R A D R I N M E E A E N U I R N R E Harrogate Way A S V 40 M H A S Y O 40 A R D I W TRU S X2 to Preston D G R K H L I E I P E V A T M N R E O D 40 A R O C N 44 I R N L O O LSWI OAD O L A C R G K T Y E A V N A A E R . S D A E E RO ’ T K X2 G S N N R TA 40 E S 40 h RS t GA 44 A a W p O D B t A o P A R Fo I Y A 47.49 D V 40 l E ta C as 44 E Co n 44 fto 40 44 F Y L D E F e D S 15 40 R O A A I G R L Crossens W H E AT R O A D 40 A N ER V P X2 D M ROAD A D O THA E L NE H 15 Y R A O L N K A D E 347 W D O A S T R R 2 E ROA R O 347 K E D O . L A 47 E F Marshside R R D T LD 2 Y FIE 2 to Preston S H A ELL 49 A 15 SH o D D 347 to Chorley u W E N t V E I R 40 W R h R I N O M D A E p A L O o R F A r N F R t 15 R N E F N Golf O P I E S T O R A D X2 U A U H L ie 44 E N R M D N I F E R r Course E S LARK Golf V 347 T E D I C Southport Town Centre Marine D A E D N S H P U R A N E O E D A B Lake A Course I R R O A E 47 calls - N S V T R C 15.15 .40.44.46.46 .47.49.315(some)X2 R K V A E A E T N S HM E K R Ocean D I 2 E O M A L O O R A R L R R R IL O P Plaza P L H H B D A D O OO D E C AD A A R D 40 O A W 40 A S U 40 O N R T K 40 EE O 40 H R Y Y D L R E C LE F T L E S E E H U V W W L 15 O N I 49 KN Y R A R R G O D E R M O A L L S A R A A D M O E L M T E M I D B A Southport C R IDG E A E B Hesketh R S M I A N T C R S Hospital O E E E A Princes E 2 D E D R .1 P A A 5. -

Background Information for Candidates

Background Information for Candidates Primary Care Networks From July 2019, NHS England made funding available for Primary Care Networks, through the national GP contract, for the creation of 7.5 Link Workers (FTE) who will work across the 7 Primary Care Networks in Sefton. A Primary Care Network (PCN) consist of groups of general practices working together with a range of local providers, including across primary care, community services, social care and the voluntary sector to offer more personalised, coordinated health and social care to their local population. Each PCN serves a patient population of between 30 and 50k. There are 7 PCN’s in Sefton. These are Bootle, Seaforth and Litherland, Crosby and Maghull, Formby, Ainsdale and Birkdale, Central Southport and North Southport. Primary Care Networks are an integral part of the recently published NHS Long-Term Plan which introduces this new role of social prescribing link workers into their multi-disciplinary teams as part of the expansion to the primary care workforce. This is an opportunity to work collaboratively with these developing PCN’s to establish this new role and shape social prescribing in Sefton. Social Prescribing Link Workers In December and January Sefton CVS recruited 7.5 FTE Social Prescribing Link Workers on behalf of host organisations, to support the delivery of a social prescribing service for Primary Care Networks in Sefton as part of the award winning Living Well Sefton programme. The social prescribing link workers are employed by a range of partner organisations working across the borough but function as one social prescribing team alongside Living Well Mentors in the wider service. -

Imagine Sefton 2030 Vision Consultation Report - August 2016 Forward by Cabinet Sponsors

Imagine Sefton 2030 Vision Consultation Report - August 2016 Forward by Cabinet Sponsors Sefton Council is leading on developing a new and exciting vision for the future of the Borough; focusing on what is important and to be bold and ambitious, so that Sefton is a place where we are all proud to live, where people want to spend time, where people can achieve and where businesses thrive and investors are drawn to. We have worked very closely with our partners, businesses, private sector organisations, the voluntary, community and faith sector and our local community to understand what you love about the area and how we can work together to deliver the ambitions expressed leading up to 2030 and beyond. It has been really important that we ask local people, visitors and people who work in the Borough what your Vision is for the Borough and the engagement we have carried out on the Vision built upon the work and the many conversations that have taken place with communities during the past few years. The extensive engagement that was carried out to help us with our understanding saw us engaging with over 3500 people of all ages from across the Borough, who visit the Borough and who have businesses here to provide us with a collective view on the areas that are important for the Borough for the future. The inclusive process included a development of a website and a Visioning Toolkit, Pop-up Community Roadshows, meetings, workshops, surveys, a comprehensive social media campaign and yes we even had answers on a postcard.