Mark Harris University of Cincinnati/Goldsmiths College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

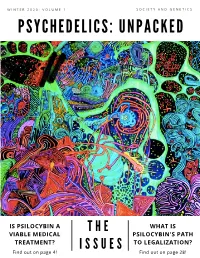

Psychedelics: Unp Acked

W I N T E R 2 0 2 0 : V O L U M E 1 S O C I E T Y A N D G E N E T I C S PSYCHEDELICS: UNPACKED IS PSILOCYBIN A T H E WHAT IS VIABLE MEDICAL PSILOCYBIN'S PATH TREATMENT? I S S U E S TO LEGALIZATION? Find out on page 4! Find out on page 28! R E A D Y TRIP? F O R Y O U R 2 Editor's Note 4 Is Psilocybin a Viable Medical Treatment? THE SCIENCE 14 Neuroscience of Depression and Anxiety 18 Antidepressants: A Current Analysis THE HISTORY 20 Psychedelics; Neuroscience of the Brain Part 1: The Shamanic 24 Part 2: The Science/Political 26 What is Psilocybin's Path to 28 Legalization? THE SOCIAL/CULTURAL 35 Unpacking Recreational Psychedelic Culture 36 How Psychedelics Have Influenced the Mainstream 01 PSYCHADELICS: UNPACKED LETTER FROM THE EDITORS Dear Distinguished Reader, By association with the countercultural When you hear the word psychedelics, it is likely that strong preconceptions will come to mind. Terms like communities that threatened the status quo, “drug,” “addict,” and “illegal” may spring to the forefront. Or psychedelics came to represent a threat to the maybe “trip,” “hallucinations” and “adventure” do. But dominant narrative, and thus have been painted as what about words like “medicine” or “treatment?” The idea dangerous. LSD was linked to addiction through of using psychedelics as potential treatment for mental mass manipulation by the government demanding illness was actually tested as early as the 1950s (Read colleges to report any activities and findings more about this history on page 26), and promising results associated with the drug. -

Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy (Exhibition Catalogue)

KINETIC MASTERS & THEIR LEGACY CECILIA DE TORRES, LTD. KINETIC MASTERS & THEIR LEGACY OCTOBER 3, 2019 - JANUARY 11, 2020 CECILIA DE TORRES, LTD. We are grateful to María Inés Sicardi and the Sicardi-Ayers-Bacino Gallery team for their collaboration and assistance in realizing this exhibition. We sincerely thank the lenders who understood our desire to present work of the highest quality, and special thanks to our colleague Debbie Frydman whose suggestion to further explore kineticism resulted in Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy. LE MOUVEMENT - KINETIC ART INTO THE 21ST CENTURY In 1950s France, there was an active interaction and artistic exchange between the country’s capital and South America. Vasarely and many Alexander Calder put it so beautifully when he said: “Just as one composes colors, or forms, of the Grupo Madí artists had an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires in 1957 so one can compose motions.” that was extremely influential upon younger generation avant-garde artists. Many South Americans, such as the triumvirate of Venezuelan Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy is comprised of a selection of works created by South American artists ranging from the 1950s to the present day. In showing contemporary cinetismo–Jesús Rafael Soto, Carlos Cruz-Diez, pieces alongside mid-century modern work, our exhibition provides an account of and Alejandro Otero—settled in Paris, amongst the trajectory of varied techniques, theoretical approaches, and materials that have a number of other artists from Argentina, Brazil, evolved across the legacy of the field of Kinetic Art. Venezuela, and Uruguay, who exhibited at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. -

Exhibition Catalogue

In memory of Denise René June 25, 1913 - July 9, 2012 Denise René at Vasarely, Galerie Denise René Rue de la Boétie, Paris, 1966 © D.R (rights reserved) FOREWORD In the spring of 2017, Puerta Roja presented the ground-breaking exhibition Carlos Cruz-Diez: Mastering Following a few years where conceptual art took over the spotlight, it was the strength of the philosophical Colour. In 2018, we present once more the works by the Franco-Venezuelan master in a joint exhibition ideals at the heart of the artists’ intent that would ensure the movement’s lasting legacy and current revival. with the iconic Galerie Denise René. The exhibition titled Movement (2018) provides historical context A myriad of retrospectives on the artists, the movement and the gallery itself have taken place in the last through the works of the artist’s contemporaries whose careers, alongside Cruz-Diez, were catapulted twenty years. In 2001, the French National Museum of Modern Art paid tribute with the exhibition The Intrepid by Denise René in the 1950s. Historical and recent works by Jesús Rafael Soto, Victor Vasarely and Denise René, a Gallery in the Adventure of Abstract Art, at the Centre Pompidou. The Pompidou would also Yaacov Agam, are accompanied by younger artists’ works, furthering the legacy of the Op and Kinetic reinstall its collection along the lines of art theory, including a dedicated section to Op and Kinetic Art. The Art movement into the twenty-first century and giving both tribute and future life to the visionary spirit Tate Modern opened A View from Zagreb: Op and Kinetic Art in 2016, a permanent room in its new building of Denise René and her artists. -

9009558 01-Victor-Vasarely-Lecture.Mp3

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-to-Reel collection Victor Vasarely, introduced by Herbert Rickman and Diane Waldman, 1984 HERBERT RICKMAN Can you hear me? You cannot hear me. Now you can hear me. Okay, I feel like this is the Academy Awards Ceremony, but I assure you I am not Johnny Carson. Now we are here to listen to Victor Vasarely in what will undoubtedly be a rather sterling speech. There are however (break in audio) HERBERT RICKMAN — urban architecture. Many of the cities of Europe today are reflective, in the best sense, of his influence, so, I am proud to read this message from the mayor and then, I want to make a presentation to Victor Vasarely. It reads, “To all in attendance, Guggenheim Museum, greetings. On behalf of the City of New York, I salute our distinguished visitor from France, the world- renowned artist, Victor Vasarely. The enduring impact of Vasarely, the father of optical art, lives in the beauty [00:01:00] and power of shape, light, color, and movement, the stuff of which light itself is made. How fortunate we New Yorkers are that Victor Vasarely is sharing his vision and genius with us once more. While I cannot join you this evening, I am very much with you in the vibrant spirit of this occasion. Accordingly, I have asked my special assistant, Herb Rickman, to relay my best wishes to one and all with a special 76th birthday congratulations to our welcome guest and superb artist, and now, honorary New Yorker, Victor Vasarely.” (applause) I’m going to pin Mister Vasarely with the — this is New York’s most significant gift, sir, and I will explain it to you later in French. -

The Psychedelic Poster Art and Artists of the Late 1960S

Focus on Topic The Psychedelic Poster Art and Artists of the late 1960s by Ted Bahr Bahr Gallery New York, USA 46 Focus on Topic The stylistic trademarks of the 1960s To advertise these concerts, both promoters turned to Wes Wilson at Contact Printing, who had been laying psychedelic poster were obscured and disguised out the primitive handbills used to advertise the Mime lettering, vivid color, vibrant energy, flowing Troupe Benefits and the Trips Festival. Wilson took organic patterns, and a mix of cultural images LSD at the Festival and was impacted by the music, from different places and periods -- anything to the scene, and the sensuous free-love sensibilities of confuse, enchant, thrill, and entertain the viewer. the hippie ethos. His posters quickly evolved to match the flowing, tripping, improvisational nature of the The style was also tribal in the sense that if you developing psychedelic music -- or “acid rock” -- and could decipher and appreciate these posters his lettering began to protrude, extend, and squeeze then you were truly a member of the hippie into every available space, mimicking and reflecting the subculture – you were hip, man. totality of the psychedelic experience. His early style culminated in the July 1966 poster for The Association which featured stylized flame lettering as the image The psychedelic poster movement coincided with the itself, a piece that Wilson considered to be the first rise of hippie culture, the use of mind-altering drugs like truly psychedelic poster. LSD, and the explosion of rock and roll. San Francisco was the center of this universe, and while prominent psychedelic poster movements also developed in London, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Austin, Bay Area artists both initiated and dominated the genre. -

An Interdisciplinary Approach to Psychedelics Jody Roun [email protected]

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Spring 2018 Under the Influence: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Psychedelics Jody Roun [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Alternative and Complementary Medicine Commons, Art Education Commons, Art Practice Commons, Cognitive Neuroscience Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, Neurosciences Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Painting Commons, Pharmacology Commons, and the Theory and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Roun, Jody, "Under the Influence: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Psychedelics" (2018). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 82. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/82 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Under the Influence: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Psychedelics A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies By Jody Alise Roun May 2018 Mentor: Dr. Suzanne Woodward Reader: Dr. Robert Smither Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida Under the Influence: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Psychedelics By Jody Alise Roun May 2018 Project Approved: ______________________________________ -

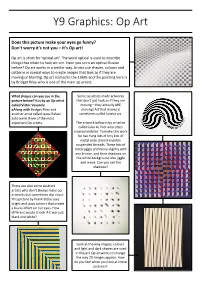

Y9 Graphics: Op Art

Y9 Graphics: Op Art Does this picture make your eyes go funny? Don't worry it's not you – it's Op art! Op art is short for 'optical art'. The word optical is used to describe things that relate to how we see. Have you seen an optical Illusion before? Op art works in a similar way. Artists use shapes, colours and patterns in special ways to create images that look as if they are moving or blurring. Op art started in the 1960s and the painting here is by Bridget Riley who is one of the main op artists. What shapes can you see in the Some op artists made artworks picture below? It is by an Op artist that don't just look as if they are called Victor Vasarely. moving – they actually ARE aAlong with Bridget Riley and moving! Art that moves is another artist called Jesus Rafael sometimes called kinetic art. Soto were three of the most important Op artists. The artwork below is by an artist called Julio Le Parc who often created mobiles. To make this work he has hung lots of tiny bits of metal onto almost invisible suspended threads. These bits of metal jiggle and move slightly with any breeze, and their shadows on the white background also jiggle and move. Can you see the shadows? There are also some abstract artists who don't always make op artworks but sometimes slip into it. This picture by Frank Stella uses bright and jazzy colours that create a buzzy effect on our eyes. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 27, 2018

Contact: Amy Schreiber Executive Assistant for Advancement and Administration 260. 422. 6467, ext. 334 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 27, 2018 Solo exhibition by Chuck Sperry, legendary rock poster artist, opens September 15 Including a sister exhibition of work from the psychedelic era opening September 8 [Fort Wayne, IN] ̶ The Fort Wayne Museum of Art is pleased to announce dual exhibitions exploring the intersection of art, music, and journalism, and their influence by the psychedelic era of the 1960s. On September 8, FWMoA will open Litmus Test: Works on Paper from the Psychedelic Era, followed by the opening of All Access: Exploring Humanism in the Art of Chuck Sperry a week later on September 15. The Psychedelic Era was, among many things, a cultural frontier for colors and imagery. Music, politics, and drugs ignited an unprecedented expansion of art revolving around these elements. From Berkeley College to the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, young idealists organized and the art of the era came to fruition. This exhibition will be our bridge to that time, showcasing a psychedelic era works on paper. The poster work and ephemera of Gary Grimshaw and the photography of Leni Sinclair will showcase the art that poured from that time and place. Blotter sheets from Mark Mothersbaugh, H.R. Giger, S. Clay Wilson, Chuck Sperry, and more will represent the creative fuel for many of the artists of the time. Also featured will be the work of the poster artists of the time: Wes Wilson, Victor Moscoso, Stanley Mouse, Rick Griffin, and Alton Kelley. -

Suddenly That Summer

July 2012 Suddenly That Summer By Sheila Weller It was billed as “the Summer of Love,” a blast of glamour, ecstasy, and Utopianism that drew some 75,000 young people to the San Francisco streets in 1967. Who were the true movers behind the Haight-Ashbury happening that turned America on to a whole new age? Photograph by Jim Marshall/Digital colorization by Lorna Clark/Permission of Jim Marshall L.L.C. FREE FOR ALL The Charlatans perform in Golden Gate Park. In a 25-square-block area of San Francisco, in the summer of 1967, an ecstatic, Dionysian mini-world sprang up like a mushroom, dividing American culture into a Before and After unparalleled since World War II. If you were between 15 and 30 that year, it was almost impossible to resist the lure of that transcendent, peer-driven season of glamour, ecstasy, and Utopianism. It was billed as the Summer of Love, and its creators did not employ a single publicist or craft a media plan. Yet the phenomenon washed over America like a tidal wave, erasing the last dregs of the martini-sipping Mad Men era and ushering in a series of liberations and awakenings that irreversibly changed our way of life. The Summer of Love also thrust a new kind of music—acid rock—across the airwaves, nearly put barbers out of business, traded clothes for costumes, turned psychedelic drugs into sacred door keys, and revived the outdoor gatherings of the Messianic Age, making everyone an acolyte and a priest. It turned sex with strangers into a mode of generosity, made “uptight” an epithet on a par with “racist,” refashioned the notion of earnest Peace Corps idealism into a bacchanalian rhapsody, and set that favorite American adjective, “free,” on a fresh altar. -

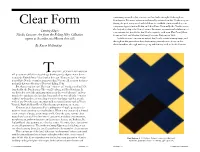

Scandinavian Review Clear Form Summer—2019

continuing up until today, concrete art has had a stronghold throughout Scandinavia. Extensive international travel by artists from the Nordic regions Clear Form during the post-war period enabled them to establish contacts with key con- temporary figures first in Berlin and then Paris. Eventually the Nordic artists also helped to shape the flow of events. In return, international exhibitions of Cutting Edges: concrete art also traveled to the Nordic capitals, such as in Klar Form (Clear Nordic Concrete Art from the Erling Neby Collection Form) in 1952 and Konkret Realisme (Concrete Realism) in 1956. opens at Scandinavia House this fall. A dedication to concrete art united the Nordic artists in many ways, and throughout the years there have been many joint efforts to focus on this shared aesthetic through various group exhibitions, such as Nordic Concrete By Karin Hellandsjø HIS FALL, SCANDINAVIA HOUSE will present an exhibition of paintings, T drawings and sculpture never before seen in the United States. Joined under the term “Concrete Art,” the works from all five Nordic countries span more than 70 years. All are from the inter- nationally known collection of Norway’s Erling Neby. But what is concrete art? The term “concrete art” was first used in 1929, launched by the Dutch artists Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian. It was devised to avoid the ambiguity inherent in the word “abstract,” and was intended to emphasize the fact that forms and colors were already “concrete realities” in themselves, not needing to refer to anything outside a specific work of art. Over the years, internationally recognized artists such as Victor Vasarely, Frank Stella and Josef Albers became prominent exponents. -

Met Press Release

News Release Communications For Immediate Release T 212 570 3951 [email protected] Julio Le Parc 1959 Contact Ann Bailis Alexandra Kozlakowski The first solo exhibition in a New York museum of Argentinian artist Julio Micol Spinazzi Le Parc (born 1928) will open at The Met Breuer on December 4, 2018. The show celebrates the artist’s extraordinary gift to The Met of 24 Exhibition Dates: works and also marks the occasion of the artist’s 90th birthday. December 4, 2018– Featuring over 50 works, Julio Le Parc 1959 will present a substantial, February 24, 2019 never-before-seen selection of gouaches from one of the most prolific and transformative years in the artist’s career. Exhibition Location: The Met Breuer, Floor 2 The exhibition is made possible by The Daniel and Estrellita Brodsky Foundation. Press Preview: Monday, December 3, Additional support is provided by Tony Bechara, the Institute for Studies 10 am–noon on Latin American Art (ISLAA), and the Latin American Art Initiative of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.metmuseum.org #MetJulioLeParc Born in Mendoza, Argentina, in 1928, Le Parc studied under Lucio Fontana during the 1940s and engaged with abstract avant-garde movements in Buenos Aires. In 1958, Le Parc moved to Paris, where his encounter with Op artists such as Victor Vasarely had an important influence on his art. The series of gouaches Le Parc started that year— intimate yet methodic studies of form and color—illuminates his interest in developing geometric abstraction by incorporating movement through variations, sequences, and progressions. This work anticipates his founding role in Kinetic art during the 1960s, when he made paintings and sculptures with movable parts by incorporating mirrors, motors, and electric light. -

Rethinking Minimalism: at the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism

Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter Shelley A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee Jonathan Bernard, Chair Áine Heneghan Judy Tsou Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music Theory ©Copyright 2013 Peter Shelley University of Washington Abstract Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter James Shelley Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Jonathan Bernard Music Theory By now most scholars are fairly sure of what minimalism is. Even if they may be reluctant to offer a precise theory, and even if they may distrust canon formation, members of the informed public have a clear idea of who the central canonical minimalist composers were or are. Sitting front and center are always four white male Americans: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. This dissertation negotiates with this received wisdom, challenging the stylistic coherence among these composers implied by the term minimalism and scrutinizing the presumed neutrality of their music. This dissertation is based in the acceptance of the aesthetic similarities between minimalist sculpture and music. Michael Fried’s essay “Art and Objecthood,” which occupies a central role in the history of minimalist sculptural criticism, serves as the point of departure for three excursions into minimalist music. The first excursion deals with the question of time in minimalism, arguing that, contrary to received wisdom, minimalist music is not always well understood as static or, in Jonathan Kramer’s terminology, vertical. The second excursion addresses anthropomorphism in minimalist music, borrowing from Fried’s concept of (bodily) presence.