The Media Contingencies of Generation Mashup: a Zˇizˇekian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Maya Ayana, "Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626527. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nf9f-6h02 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, Georgetown University, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, George Mason University, 2002 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2007 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Maya Ayana Johnson Approved by the Committee, February 2007 y - W ^ ' _■■■■■■ Committee Chair Associate ssor/Grey Gundaker, American Studies William and Mary Associate Professor/Arthur Krrtght, American Studies Cpllege of William and Mary Associate Professor K im b erly Phillips, American Studies College of William and Mary ABSTRACT In recent years, a number of young female pop singers have incorporated into their music video performances dance, costuming, and musical motifs that suggest references to dance, costume, and musical forms from the Orient. -

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

The Best Totally-Not-Planned 'Shockers'

Style Blog The best totally-not-planned ‘shockers’ in the history of the VMAs By Lavanya Ramanathan August 30 If you have watched a music video in the past decade, you probably did not watch it on MTV, a network now mostly stuck in a never-ending loop of episodes of “Teen Mom.” This fact does not stop MTV from continuing to hold the annual Video Music Awards, and it does not stop us from tuning in. Whereas this year’s Grammys were kind of depressing, we can count on the VMAs to be a slightly morally objectionable mess of good theater. (MTV has been boasting that it has pretty much handed over the keys to Miley Cyrus, this year’s host, after all.) [VMAs 2015 FAQ: Where to watch the show, who’s performing, red carpet details] Whether it’s “real” or not doesn’t matter. Each year, the VMAs deliver exactly one ugly, cringe-worthy and sometimes actually surprising event that imprints itself in our brains, never to be forgotten. Before Sunday’s show — and before Nicki Minaj probably delivers this year’s teachable moment — here are just a few of those memorable VMA shockers. 1984: Madonna sings about virginity in front of a blacktie audience It was the first VMAs, Bette Midler (who?) was co-hosting and the audience back then was a sea of tux-wearing stiffs. This is all-important scene-setting for a groundbreaking performance by young Madonna, who appeared on the top of an oversize wedding cake in what can only be described as head-to-toe Frederick’s of Hollywood. -

Statement on the Dangers of Guardianship in Response to Britney Spears’S Testimony

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: MEDIA CONTACT: Elizabeth Seaberry June 24, 2021 Communications Specialist Disability Rights Oregon Email: [email protected] Mobile: 503.444.0026 Statement on the dangers of guardianship in response to Britney Spears’s testimony Portland, Oregon—Today, Disability Rights Oregon Executive Director Jake Cornett issued the following statement in response to the Britney Spears’s testimony yesterday regarding her conservatorship. Statement from Jake Cornett, Executive Director, Disability Rights Oregon As Britney Spears’s case illustrates, one of the most restrictive things that can happen to a person is having a conservator or guardian be given the power to make crucial life decisions for them. Conservatorships or guardianships take away an individual’s right to make decisions about all aspects of their life, including where they live, what healthcare they get, and how they spend their time and money. Alarmingly, these enormous changes can be made while the person has little to no voice in the process or the chance to object. And conservatorships or guardianships can last a lifetime. Conservatorships and guardianships should be used as little as possible and truly as a last resort. Instead, less restrictive alternatives should be used, alternatives that allow a person to retain as much autonomy over their own life and independence as possible. Whether under conservatorship or guardianship or not, people with disabilities should have optimal freedom, independence, and the basic right to live the life that they choose -

September 2020

Page: 1 Redox D.A.S. Artist List for period: 01.09.2020 - 30.09.2020 Date time: Number: Title: Artist: Publisher Lang: 01.09.2020 00:03:05 HD 028096 IT DON'T MAKE ANY DIFFERENCE TO MEKEVIN MICHAEL FEAT. WYCLEF ATLANTIC 00:03:43 ANG 01.09.2020 00:06:46 HD 002417 KAMOR ME VODI SRCE NUŠA DERENDA RTVS 00:03:16 SLO 01.09.2020 00:10:09 HD 020765 THE MIDNIGHT SPECIAL CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL ZYX MUSIC 00:04:09 ANG 01.09.2020 00:14:09 HD 029892 ZABAVA TURBO ANGELS RTS 00:02:59 SLO 01.09.2020 00:17:06 HD 069164 KILOGRAM NA DAN VICTORY 00:03:20 SLO 01.09.2020 00:20:42 HD 015945 SOMEBODY TO LOVE JEFFERSON AIRPLANE BMG, POLYGRAM,00:02:56 SONY ANG 01.09.2020 00:23:36 HD 054272 UBRANO JAMRANJE ŠALEŠKI ŠTUDENTSKI OKTET 00:05:54 SLO 01.09.2020 00:29:31 HD 004863 RELIGIJA LJUBEZNI REGINA MEGATON 00:03:00 SLO 01.09.2020 00:32:35 HD 017026 F**K IT FLORIDA INC KONTOR 00:03:59 ANG 01.09.2020 00:36:32 HD 028307 BOBMBAY DREAMS ARASH FEAT REBECCA AND ANEELA ORPHEUS MUSIC00:02:51 ANG 01.09.2020 00:39:23 HD 029465 DUM, DUM, DUM POP DESIGN 00:04:02 SLO 01.09.2020 00:43:35 HD 025553 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHRIS ISAAK REPRISE 00:03:17 ANG 01.09.2020 00:46:50 HD 037378 KOM TIMOTEIJ UNIVERSAL 00:02:56 ŠVEDSKI 01.09.2020 00:49:46 HD 017718 VSE (REMIX) ANJA RUPEL DALLAS 00:03:59 SLO 01.09.2020 00:53:51 HD 012771 YOU ARE MY NUMBER ONE SMASH MOUTH INTERSCOPE00:02:28 ANG 01.09.2020 00:56:17 HD 021554 39,2 CECA CECA MUSIC00:05:49 SRB 01.09.2020 01:02:04 HD 024103 ME SPLOH NE BRIGA ROGOŠKA SLAVČKA 00:03:13 SLO 01.09.2020 01:05:47 HD 002810 TOGETHER FOREVER RICK ASTLEY -

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

ALLA Press Release May 26 2015 FINAL

! ! ! A$AP ROCKY’S NEW ALBUM AT.LONG.LAST.A$AP AVAILABLE NOW ON A$AP WORLDWIDE/POLO GROUNDS MUSIC/RCA RECORDS TRENDING NO. 1 ON ITUNES IN THE US, UK, CANADA, AUSTRALIA, FRANCE, GERMANY AND MORE SOPHOMORE ALBUM FEATURES APPEARANCES BY KANYE WEST, LIL WAYNE, ScHOOLBOY Q, MIGUEL, ROD STEWART, MARK RONSON, MOS DEF, JUICY J, JOE FOX AND OTHERS [New York, NY – May 26, 2015] A$AP Rocky released his highly anticipated new album, At.Long.Last.A$AP, today (5/26) due to the album leaking a week prior to its scheduled June 2nd release date. The album is currently No. 1 at iTunes in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, France, Germany, Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, Poland, Switzerland, Russia and more. The follow-up to the charismatic Harlem MC’s 2013 release, Long.Live.A$AP, A$AP Rocky’s sophomore album, features a stellar line up of guest appearances by Rod Stewart, Miguel and Mark Ronson on “Everyday,” ScHoolboy Q on “Electric Body,” Lil Wayne on a new version of the previously released “M’$,” Kanye West and Joe Fox on “Jukebox Joints,” plus Mos Def, Juicy J, UGK and more on other standout tracks. Producers Danger Mouse, Jim Jonsin, Juicy J and Mark Ronson among others, contributes to the album’s trippy new sound. Executive Producers include Danger Mouse, A$AP Yams and A$AP Rocky with Co-Executive Producers Hector Delgado, Juicy J, Chace Johnson, Bryan Leach and AWGE. In 2013, A$AP Rocky announced his global arrival in a major way with his chart- topping debut album LONG.LIVE.A$AP. -

Империя Jay Z: Как Парень С Улицы Попал В Список Forbes Zack O'malley Greenburg Empire State of Mind: How Jay Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office

Зак Гринберг Империя Jay Z: Как парень с улицы попал в список Forbes Zack O'Malley Greenburg Empire State of Mind: How Jay Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office Copyright © 2011, 2012, 2015 by Zack O’Malley Greenburg All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition published by arrangement with Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC © Гусева А., перевод, 2017 © Оформление. ООО «Издательство «Эксмо», 2017 * * * Введение Четвертого октября 1969 года в 00 часов 10 минут по верхнему уровню Мертл- авеню в последний раз прогрохотал поезд наземки, навсегда скрывшись в ночи[1]. Два месяца спустя Шон Кори Картер, более известный как Jay Z, появился на свет и обрел свой первый дом в расположенном поблизости Марси Хаузес. Сейчас этот раскинувшийся на значительной территории комплекс однообразных шестиэтажных кирпичных зданий отделен пятью жилыми блоками от призрачных руин линии Мертл- авеню, вытянутой полой конструкции, которую никто так и не потрудился снести. В годы формирования личности Jay Z остальная территория Бедфорд-Стайвесант подобным же образом игнорировалась властями. В 1980-е, с расцветом наркоторговли, уроки спроса и предложения можно было получить за каждым углом. Прошлое Марси до сих пор дает о себе знать: железные ворота с внушительными замками, охраняющие парковочные места; номера квартир, белой краской выписанные по трафарету под каждым окном, выходящим на улицу, призванные помочь полиции в поисках скрывающихся преступников; и, конечно, скелет железной дороги над Мертл-авеню, буквально в нескольких шагах от современной станции, на которой теперь останавливаются поезда маршрутов J и Z. На этих страницах вы найдете подробную историю пути Jay Z от безрадостных улиц Бруклина к высотам мира бизнеса. -

The Grey Album and Musical Composition in Configurable Culture

What Did Danger Mouse Do? The Grey Album and Musical Composition in Configurable Culture This article uses The Grey Album, Danger Mouse’s 2004 mashup of Jay-Z’s Black Album with the Beatles’“White Album,” to explore the ontological status of mashups, with a focus on determining what sort of creative work a mashup is. After situating the album in relation to other types of musical borrowing, I provide brief analyses of three of its tracks and build upon recent research in configurable-music practices to argue that the album is best conceptualized as a type of musical performance. Keywords: The Grey Album, The Black Album, the “White Album,” Danger Mouse, Jay-Z, the Beatles, mashup, configurable music. Downloaded from captions. What’s most embarrassing about this is how http://mts.oxfordjournals.org/ immensely improved both cartoons turned out to be.”2 n 1989 Gary Larson published The PreHistory of The Far Larson’s tantalizing use of quotation marks around “acci- Side, a retrospective of his groundbreaking cartoon. In a dentally” implies that the editor responsible for switching the I section of the book titled Mistakes—Mine and Theirs, captions may have done so deliberately. If we assume this to be Larson discussed a couple of curious instances when the Dayton the case and agree that both cartoons are improved, a number of Daily News switched the captions for The Far Side with the one questions emerge. What did the editor do? He/she did not for Dennis the Menace, its neighbor on the comics page. The come up with a concept, did not draw a cartoon, and did not first of these two instances had, by far, the funnier result: on the compose a caption. -

Client and Artist List

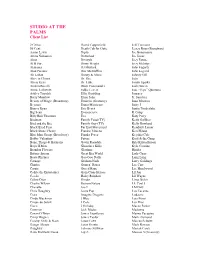

STUDIO AT THE PALMS Client List 2 Cellos David Copperfield Jeff Timmons 50 Cent Death Cab for Cutie Jersey Boys (Broadway) Aaron Lewis Diplo Joe Bonamassa Akina Nakamori Disturbed Joe Jonas Akon Divinyls Joey Fatone Al B Sure Dizzy Wright Joey McIntyre Alabama DJ Mustard John Fogarty Alan Parsons Doc McStuffins John Legend Ali Lohan Donny & Marie Johnny Gill Alice in Chains Dr. Dre JoJo Alicia Keys Dr. Luke Jordin Sparks Andrea Bocelli Duck Commander Josh Gracin Annie Leibovitz Eddie Levert Jose “Pepe” Quintano Ashley Tinsdale Ellie Goulding Journey Barry Manilow Elton John Jr. Sanchez Beauty of Magic (Broadway) Eminem (Grammy) Juan Montero Beyonce Ennio Morricone Juicy J Bianca Ryan Eric Benet Justin Timberlake Big Sean Evanescence K Camp Billy Bob Thornton Eve Katy Perry Birdman Family Feud (TV) Keith Galliher Bird and the Bee Family Guy (TV) Kelly Rowland Black Eyed Peas Far East Movement Kendrick Lamar Black Stone Cherry Frankie Moreno Keri Hilson Blue Man Group (Broadway) Franky Perez Keyshia Cole Bobby Valentino Future Kool & the Gang Bone, Thugs & Harmony Gavin Rossdale Kris Kristofferson Boyz II Men Ghostface Killa Kyle Cousins Brandon Flowers Gloriana Hinder Britney Spears Great Big World Lady Gaga Busta Rhymes Goo Goo Dolls Lang Lang Carnage Graham Nash Larry Goldings Charise Guns n’ Roses Lee Carr Cassie Gucci Mane Lee Hazelwood Cedric the Entertainer Gym Class Heroes Lil Jon Cee-lo Haley Reinhart Lil Wayne Celine Dion Hinder Limp Bizkit Charlie Wilson Human Nature LL Cool J Chevelle Ice-T LMFAO Chris Daughtry Icona Pop Los -

Adele and 'Body Image'

Adele and ‘Body Image’: Here we have an Ipad displaying a common view of body image that adolescents encounter, which is negative and destructive to self-esteem. We offer, instead, an image of Adele and a quote that is both positive and relatable. Adele presents a happy, healthy body image, one that is not necessarily mainstream. • According to an ongoing study funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, in a survey of 9 and 10 year old girls, 40% have tried to lose weight. • In a study on 10-year-old fifth graders, both girls and boys told researchers they were dissatisfied with their own bodies after watching a music video by Britney Spears or a clip from the TV show "Friends". • A 1996 study found that the amount of time adolescents spend watch soap operas, movies and music videos directly affects their perception of the human body. • One study reports that at age thirteen, 53% of American girls are "unhappy with their bodies." This percentage typically increases to 78% by the time these girls reach seventeen years old. Source: National Institute on Media and the Family A Kaiser Foundation study by Nancy Signorielli found that: In movies, particularly, but also in television shows and the accompanying commercials, women's and girls' appearance is frequently commented on. 58% of female characters in movies had comments made about their appearance. 28% of female characters in television shows and 26 percent of the female models in the accompanying commercials had comments made regarding their image. Mens' and boys' appearance is talked about significantly less often in all three media: a quarter (24%) of male characters in the movies, and 10 percent and 7 percent, respectively, in television shows and commercials. -

WXYC Brings You Gems from the Treasure of UNC's Southern

IN/AUDIBLE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR a publication of N/AUDIBLE is the irregular newsletter of WXYC – your favorite Chapel Hill radio WXYC 89.3 FM station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, seven days a week out of the Student Union on the UNC campus. The last time this publication came out in 2002, WXYC was CB 5210 Carolina Union Icelebrating its 25th year of existence as the student-run radio station at the University of Chapel Hill, NC 27599 North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This year we celebrate another big event – our tenth anni- USA versary as the first radio station in the world to simulcast our signal over the Internet. As we celebrate this exciting event and reflect on the ingenuity of a few gifted people who took (919) 962-7768 local radio to the next level and beyond Chapel Hill, we can wonder request line: (919) 962-8989 if the future of radio is no longer in the stereo of our living rooms but on the World Wide Web. http://www.wxyc.org As always, new technology brings change that is both exciting [email protected] and scary. Local radio stations and the dedicated DJs and staffs who operate them are an integral part of vibrant local music communities, like the one we are lucky to have here in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Staff NICOLE BOGAS area. With the proliferation of music services like XM satellite radio Editor-in-Chief and Live-365 Internet radio servers, it sometimes seems like the future EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nicole Bogas of local radio is doomed.