The University of Chicago Curating Value

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Article Stability and Complexity Analysis of Temperature Index Model Considering Stochastic Perturbation

Hindawi Advances in Mathematical Physics Volume 2018, Article ID 2789412, 18 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2789412 Research Article Stability and Complexity Analysis of Temperature Index Model Considering Stochastic Perturbation Jing Wang Faculty of Science, Bengbu University, Bengbu 233030, China Correspondence should be addressed to Jing Wang; [email protected] Received 20 October 2017; Accepted 12 December 2017; Published 1 January 2018 Academic Editor: Giampaolo Cristadoro Copyright © 2018 Jing Wang. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. A temperature index model with delay and stochastic perturbation is constructed in this paper. It explores the infuence of parameters and stochastic factors on the stability and complexity of the model. Based on historical temperature data of four cities of Anhui Province in China, the temperature periodic variation trends of approximately sinusoidal curves of four cities are given, respectively. In addition, we analyze the existence conditions of the local stability of the temperature index model without stochastic term and estimate its parameters by using the same historical data of the four cities, respectively. Te numerical simulation results of the four cities are basically consistent with the descriptions of their historical temperature data, which proves that the temperature index model constructed has good ftting degree. It also shows that unreasonable delay parameter can make the model lose stability and improve the complexity. Stochastic factors do not usually change the trend in temperature, but they can cause high frequency fuctuations in the process of temperature evolution. -

Local Arrangements and Some Tips for Attending COCOA'2009

Local Arrangements and Some Tips for Attending COCOA’2009 (1) Registering on Site (1.1) A registration desk will be set up at the Lobby of the conference hotel. (1.2) Registration time is 14:00-20:00 on June 9 and 08:30-12:00 on June 10. For other time you may register at the room of organization committee. (1.3) A package of conference materials will be provided for each participant who has paid the registration fee. It includes a copy of proceedings, a copy of program, your conference name tag, a ball pen, a notebook, a set of tickets for all organized lunches/suppers/banquet/tour, a map of Huangshan. (1.4) You MUST wear your conference name tag and give your tickets to waiter/waitress when attending all sessions and taking all organized reception/lunches/banquet/tour. (2) Presenting Papers (2.1) All talks MUST be presented in one of the forms of ppt, pdf, doc, ps files. NO projector for transparent slides will be provided (we are very sorry for inconvenience). (2.2) You can either bring your own laptop, or bring a mobile hard disk, USB disk with your files saved. (2.3) Meeting rooms for all plenary and parallel sessions are on the 1st floor at the conference center of the hotel (which is in a separate building). (3) Attending One-day Tour (3.1) An one-day tour for sightseeing of Huangshan is organized on June 12 (http://www.uhuangshan.com/). (3.2) All participants must summon outside the hotel at 07:30. -

Annual Report 2005

Annual Report 2005 NSW Department of Education and Training Published by Strategic Planning and Regulation NSW Department of Education and Training (DET) 35 Bridge Street Sydney NSW 2000 ISSN 1442-3898 The Annual Report is available from Planning and Innovation Directorate, DET Level 5, 35 Bridge Street, Sydney NSW 2000, and online from: www.det.nsw.edu.au/annualreports The estimated cost of production and printing the publication was $26,300. The Department’s office hours are from 9:00am to 5:00pm Monday to Friday. State, Regional and Institute office addresses and telephone numbers are listed on the inside back cover. Cover Photo Northern Beaches Secondary College. This college was awarded the NSW VET Excellence Award. Letter of Submission to the Minister The Hon Ms Carmel Tebbutt MP Minister for Education and Training Level 33, Governor Macquarie Tower 1 Farrer Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 Dear Minister It is with pleasure that I submit the annual report of the NSW Department of Education and Training for the year ended 31 December 2005. The report has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Annual Reports (Departments) Act 1985 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983 and regulations under those Acts, and it is submitted to you for presentation to the NSW Parliament. This report contains details of the Department’s performance in implementing strategic priorities in NSW public schools, TAFE NSW, Adult and Community Education, Adult Migrant English Services, higher education and the National Art School. It also contains the Department’s audited financial statements for the year ended 30 June 2005. -

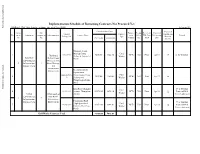

Procured Contracts February/13

Implementation Schedule of Remaining Contracts Not Procured Yet Public Disclosure Authorized 1USD=6.3 CNY (based on the exchange rate as of Nov, 2012) February/13 Estimated Base Costs Expected Comp- Sub- Procure- Prequa- Review by Expected Contract Contract Construction No. onent Component component Sub-component Contract Name ment lifica- WB (Prior Bid Opening Remark Package No. Type Duration No. No. Mothod tion /Post) Date CNY10,000 USD10,000 (month) Wuxiaojie Storm Drainage Pump Civil 1 HSFS/S5/C1 7200.00 1142.86 NCB NO Prior Jan/13 17 in the bidding Huaishang Station & Associated Works Suburban District Flood Public Disclosure Authorized Works Environment Management & 3 Infrastructure 3 Storm Drainage Improvement and Infrastructure Reconstruction & Improvement Expansion of HSFS/S5/C6-N- Wangxiaogou Pump Civil 2 3478.00 552.06 NCB NO Post Apr/13 16 B Stations and Works Wangxiaogou Intake Ditch Public Disclosure Authorized Lilou Road (Donghai New Addition Civil 4 LZUI/S10/C1 Avenue - Huangshan 10572.00 1678.10 NCB NO Prior Apr/13 12 Project of Mid- Works Urban Urban(south of Avenue) Term Adjustment Environment Huai River) 2 3 Infrastructure Infrastructure Fengandong Road Improvement Improvement New Addition (High Speed Rail Civil 5 LZUI/S10/C2 10351.00 1643.02 NCB NO Prior Apr/13 12 Project of Mid- Culvert - Mid. Ring Works Term Adjustment Road) Civil Works Contracts Total 31601.00 5016.03 Public Disclosure Authorized Preparation of Rules and Operational Procedures for Mohekou Industrial Bid evaluation 6 C Zone (MIZ), and - 20 TA QCBS - Prior Aug/12 12 is in process Bidding Document to Select a Professional Technical Operator for MIZ Services, 4 Training and Study Tour Institutional & Financial Bid evaluation 7 E - 32 TA QBS - Prior Aug/12 12 Strengthening of is in process Utility Companies Strategy and Selection of Bengbu 8 F - 21 TA CQS - Prior Mar/13 7 Water Sector Development TA and Training Total - 73 Procured Contracts February/13 Review Estimated Cost Cost of Signed Contract Procure- Contract by WB Bid Opening Contract No. -

Study on the Influence of Tourists' Value on Sustainable Development of Huizhou Traditional Villages

E3S Web of Conferences 23 6 , 03007 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123603007 ICERSD 2020 Study on the Influence of Tourists’ Value on Sustainable Development of Huizhou Traditional Villages-- A Case of Hongcun and Xidi QI Wei 1, LI Mimi 2*, XIAO Honggen2, ZHANG Jinhe 3 1Anhui Technical College of Industry and Economy, Hefei, Anhui 2School of Hotel and Tourism Management, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong 3School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu Abstract: The tourists’ value of traditional village representing personal values, influences the tourists’ behavior deeply. This paper, with the soft ladder method of MEC theory from the perspective of the tourist, studies the value of tourists born in the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s of the traditional villages in Hongcun and Xidi, which indicates 39 MEC value chains, and reveals 11 important attributes of Huizhou traditional villages, 16 tourism results, and 9 types of tourists’ values. With constructing a sustainable development model of Huizhou traditional villages based on tourists’ value, it shows an inherent interaction between tourists’ value and traditional village attributes subdividing the tourism products and marketing channels of Huizhou traditional villages, which is of great significance to the sustainable development of traditional villages in Huizhou. 1 Introduction connection between value and the attributes of traditional villages, to activate traditional village tourism Traditional villages refer to the rural communities, with and realize the sustainable development of traditional historical inheritance of certain ideology, culture, villages. customs, art and social-economic values, rural communities, formed by people with common values who gather together with agriculture as the basic content 2 Theoretical Basis of economic activities, including ancient villages, cultural historical villages, world heritage villages, 2.1 The Sustainable Development of Traditional etc.[1-3]. -

Chinese Language Learning in the Early Grades

Chinese Language Learning in the Early Grades: A Handbook of Resources and Best Practices for Mandarin Immersion Asia Society is the leading global and pan-Asian organization working to strengthen relationships and promote understanding among the peoples, leaders, and institutions of Asia and the United States. We seek to increase knowledge and enhance dialogue, encourage creative expression, and generate new ideas across the fields of policy, business, education, arts, and culture. The Asia Society Partnership for Global Learning develops youth to be globally competent citizens, workers, and leaders by equipping them with the knowledge and skills needed for success in an increasingly interconnected world. AsiaSociety.org/Chinese © Copyright 2012 by the Asia Society. ISBN 978-1-936123-28-5 Table of Contents 3 Preface PROGRAM PROFILE: By Vivien Stewart 34 The Utah Dual Language Immersion Program 5 Introduction 36 Curriculum and Literacy By Myriam Met By Myriam Met 7 Editors’ Note and List of Contributors PROGRAM PROFILE: 40 Washington Yu Ying Public Charter School 9 What the Research Says About Immersion By Tara Williams Fortune 42 Student Assessment and Program Evaluation By Ann Tollefson, with Michael Bacon, Kyle Ennis, PROGRAM PROFILE: Carl Falsgraf, and Nancy Rhodes 14 Minnesota’s Chinese Immersion Model PROGRAM PROFILE: 16 Basics of Program Design 46 Global Village Charter Collaborative, By Myriam Met and Chris Livaccari Colorado PROGRAM PROFILE: 48 Marketing and Advocacy 22 Portland, Oregon Public Schools By Christina Burton Howe -

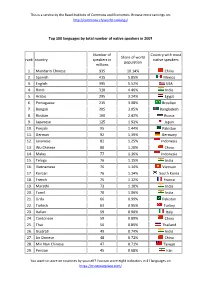

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Cantonese Vs. Mandarin: a Summary

Cantonese vs. Mandarin: A summary JMFT October 21, 2015 This short essay is intended to summarise the similarities and differences between Cantonese and Mandarin. 1 Introduction The large geographical area that is referred to as `China'1 is home to many languages and dialects. Most of these languages are related, and fall under the umbrella term Hanyu (¡£), a term which is usually translated as `Chinese' and spoken of as though it were a unified language. In fact, there are hundreds of dialects and varieties of Chinese, which are not mutually intelligible. With 910 million speakers worldwide2, Mandarin is by far the most common dialect of Chinese. `Mandarin' or `guanhua' originally referred to the language of the mandarins, the government bureaucrats who were based in Beijing. This language was based on the Bejing dialect of Chinese. It was promoted by the Qing dynasty (1644{1912) and later the People's Republic (1949{) as the country's lingua franca, as part of efforts by these governments to establish political unity. Mandarin is now used by most people in China and Taiwan. 3 Mandarin itself consists of many subvarities which are not mutually intelligible. Cantonese (Yuetyu (£) is named after the city Canton, whose name is now transliterated as Guangdong. It is spoken in Hong Kong and Macau (with a combined population of around 8 million), and, owing to these cities' former colonial status, by many overseas Chinese. In the rest of China, Cantonese is relatively rare, but it is still sometimes spoken in Guangzhou. 2 History and etymology It is interesting to note that the Cantonese name for Cantonese, Yuetyu, means `language of the Yuet people'. -

Inside Information Bankruptcy and Liquidation of a Subsidiary of the Company

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. (a sino-foreign joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China) (Stock Code: 00991) INSIDE INFORMATION BANKRUPTCY AND LIQUIDATION OF A SUBSIDIARY OF THE COMPANY This announcement is made by Datang International Power Generation Co., Ltd. (the “Company”) pursuant to Part XIVA of the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571, Laws of Hong Kong) and Rules 13.09(2)(a) and 13.10B of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited(the “Hong Kong Listing Rules”). This announcement is also made by the Company pursuant to Rules 13.25(1), 13.51B(2) and 13.51(2)(l) of the Hong Kong Listing Rules. The board of directors of the Company (the “Board”) announced that Datang Anqing Biomass Power Generation Co., Ltd. (“Anqing Company”), a holding subsidiary of the Company, received the Civil Ruling from the People’s Court of Daguan District, Anqing City, Anhui Province ((2021) Wan 0803 Po Shen No. 1) recently. 1. OVERVIEW OF THE BANKRUPTCY AND LIQUIDATION Anqing Company applied to the People’s Court of Daguan District, Anqing City, Anhui Province for the bankruptcy and liquidation on the ground that it was unable to settle its due debts and its assets were insufficient to pay off all its debts. -

Huangshan Hongcun Two Day Tour

! " # Guidebook $%&' Hefei Overview Hefei, capital of Anhui Province, is located in the middle part of China between the Yangtze River and the Huaihe River and beside Chaohu Lake. It occupies an area of 7,029 square kilometers of which the built-up urban area is 838.52 square kilometers. With a total population of about five million, the urban residents number about 2.7 million. As the provincial seat, the city is the political, economic, cultural, commercial and trade, transportation and information centre of Anhui Province as well as one of the important national scientific research and education bases. $% !() Hefei Attractions *+, The Memorial Temple Of Lord Bao The full name of this temple is the Memorial Temple of Lord Bao Xiaoshu. It was constructed in memory of Bao Zheng, who is idealized as an upright and honest official and a political reformer in the Song Dynasty. Xiaoshu is Lord Bao's posthumous name that was granted by Emperor Renzhong of the Song Dynasty in order to promote Lord Bao's contribution to the country. Former Residence of Li Hongzhang Lord Bao 1 -./01 Former Residence of Li Hongzhang Former Residence of Li Hongzhang is located on the Huaihe Road (the mid-section) in Hefei. It was built in the 28th year of the reign of Emperor Guangxu of the Qing Dynasty. The entire building looks magnificent with carved beams and rafters. It is the largest existing and best preserved former residence of a VIP in Hefei and is a key cultural relic site under the protection of Anhui Provincial Government. -

Language Contact in Nanning: Nanning Pinghua and Nanning Cantonese

20140303 draft of : de Sousa, Hilário. 2015a. Language contact in Nanning: Nanning Pinghua and Nanning Cantonese. In Chappell, Hilary (ed.), Diversity in Sinitic languages, 157–189. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Do not quote or cite this draft. LANGUAGE CONTACT IN NANNING — FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF NANNING PINGHUA AND NANNING CANTONESE1 Hilário de Sousa Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, École des hautes études en sciences sociales — ERC SINOTYPE project 1 Various topics discussed in this paper formed the body of talks given at the following conferences: Syntax of the World’s Languages IV, Dynamique du Langage, CNRS & Université Lumière Lyon 2, 2010; Humanities of the Lesser-Known — New Directions in the Descriptions, Documentation, and Typology of Endangered Languages and Musics, Lunds Universitet, 2010; 第五屆漢語方言語法國際研討會 [The Fifth International Conference on the Grammar of Chinese Dialects], 上海大学 Shanghai University, 2010; Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Conference 21, Kasetsart University, 2011; and Workshop on Ecology, Population Movements, and Language Diversity, Université Lumière Lyon 2, 2011. I would like to thank the conference organizers, and all who attended my talks and provided me with valuable comments. I would also like to thank all of my Nanning Pinghua informants, my main informant 梁世華 lɛŋ11 ɬi55wa11/ Liáng Shìhuá in particular, for teaching me their language(s). I have learnt a great deal from all the linguists that I met in Guangxi, 林亦 Lín Yì and 覃鳳餘 Qín Fèngyú of Guangxi University in particular. My colleagues have given me much comments and support; I would like to thank all of them, our director, Prof. Hilary Chappell, in particular. Errors are my own. -

Mandarin Chinese As a Second Language: a Review of Literature Wesley A

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Honors Research Projects College Fall 2015 Mandarin Chinese as a Second Language: A Review of Literature Wesley A. Spencer The University Of Akron, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Spencer, Wesley A., "Mandarin Chinese as a Second Language: A Review of Literature" (2015). Honors Research Projects. 210. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/210 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Running head: MANDARIN CHINESE AS A SECOND LANGUAGE 1 Mandarin Chinese as a Second Language: A Review of Literature Abstract Mandarin Chinese has become increasing prevalent in the modern world. Accordingly, research of Chinese as a second language has developed greatly over the past few decades. This paper reviews research on the difficulties of acquiring a second language in general and research that specifically details the difficulty of acquiring Chinese as a second language.