LE PROPHÈTE “ a Package of New Scores Lay on My Piano, Unopened [...]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Discography by Claus Nyvang Kristensen - Cds and Dvds Cnk.Dk Latest Update: 10 April 2021 Label and ID-Number Available; Not Shown

A discography by Claus Nyvang Kristensen - CDs and DVDs cnk.dk Latest update: 10 April 2021 Label and ID-number available; not shown Alain, Jean (1911-1940) Deuxième Fantaisie Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Intermezzo Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Le jardin suspendu Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Litanies Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Suite pour orgue Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Trois danses Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Variations sur un thème de Janequin Marie-Claire Alain (1972) Albéniz, Isaac (1860-1909) España, op. 165: No. 2 Tango in D major Leopold Godowsky (1920) España, op. 165: No. 2 Tango in D major (Godowsky arrangement) Carlo Crante (2011) Emanuele Delucchi (2015) Marc-André Hamelin (1987) Wilhelm Backhaus (1928) Iberia, Book 2: No. 3 Triana (Godowsky arrangement) Carlo Crante (2011) David Saperton (1957) Albinoni, Tomaso (1671-1751) Adagio in G minor (Giazotto completion) (transcription for trumpet and organ) Maurice André, Jane Parker-Smith (1977) Violin Sonata in A minor, op. 6/6: 3rd movement, Adagio (transcription for trumpet and organ) Maurice André, Hedwig Bilgram (1980) Alkan, Charles-Valentin (1813-1888) 11 Grands Préludes et 1 Transcription du Messie de Hændel, op. 66 Kevin Bowyer (2005) 11 Grands Préludes et 1 Transcription du Messie de Hændel, op. 66: No. 1 Andantino Nicholas King (1992) 11 Grands Préludes et 1 Transcription du Messie de Hændel, op. 66: Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11 (da Motta transcription for piano four hands) Vincenzo Maltempo, Emanuele Delucchi (2013) 11 Pièces dans le Style Religieux et 1 Transcription du Messie de Hændel, op. 72 Kevin Bowyer (2005) 13 Prières pour Orgue, op. -

Recital E Paesaggio Urbano Nell'ottocento

RECITAL E PAESAGGIO URBANO NELL’OTTOCENTO CONVEGNO INTERNAZIONALE 11-13 luglio 2013, La Spezia, Italy CAMEC (Centro di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) organizzato da Società dei Concerti, La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane – Centre de musique romantique française, Venezia COMITATO SCIENTIFICO ANDREA BARIZZA (Società dei Concerti della Spezia) RICHARD BÖSEL (Istituto Storico Austriaco, Roma) ROBERTO ILLIANO (Società dei Concerti della Spezia / Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) ÉTIENNE JARDIN (Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) FULVIA MORABITO (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) MASSIMILIANO SALA (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) ROHAN H. STEWART-MACDONALD (Stratford-Upon-Avon, UK) KEYNOTE SPEAKERS RICHARD BÖSEL (Istituto Storico Austriaco, Roma) LAURE SCHNAPPER (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales-EHESS, Parigi) GIOVEDÌ 11 LUGLIO ore 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Attilio Ferrero (Presidente della Società dei Concerti) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Saluti istituzionali 11.30-12.30: Il Recital solistico: nascita e sviluppo di un genere (Chair: Richard Bösel, Istituto Storico Austriaco, Rome) • MARIA WELNA (Sydney Conservatorium of Music, The University of Sydney, AUS): The Solo Recital – A Lost Performance Tradition • GEORGE BROCK-NANNESTAD (Patent Tactics, -

Toccata Classics TOCC0157 Notes

P CHARLES-VALENTIN ALKAN AND HIS RECUEILS DE CHANTS, VOLUME ONE by Peter McCallum Alkan’s ive books of Chants were written over a iteen-year period from 1857 to 1872 during his • Douze études dans les tons mineurs most artistically mature and productive phase, ater he emerged from a period of self-imposed • Cavatina from Beethoven’s String Quartet in B lat major Op.130, arr. Alkan (in social and artistic seclusion. In spite of their expressive variety, they are uniied both internally and over the complete ive-volume cycle, the ith book returning to some of the characteristics • Le Festin d’Ésope of the irst book, ending with a relective summary.1 Unlike the Opp. 35 and 39 studies, they are not the alpha and omega of his achievement, but rather a more subtle and intricate map of the • Symphonie strands and range of his musical thought. It is a characteristic of all of Alkan’s best music that – although he works within the harmonic • Twelve Studies in All the Major Keys and tonal language, the range of genres and the stylistic parameters of the nineteenth century – he brings to each of them a singular personality deined by the sense of far-sighted clarity that • Concerto for solo piano, Op. 39, Nos. 8–10; comes with isolation. Such isolation inds beautiful, poignant and varied expression in G minor Barcarolles that conclude each of the ive volumes of Chants. His sentimental moods (oten found in the E major pieces that open each set) are tinged with yearning and a sense that such comfort is for others; instead, as later with Mahler and Shostakovich, he is haunted by visions of parody, the banal and the grotesque. -

Tocc0470booklet.Pdf

FRITZ HART: MUSIC FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO, VOLUME ONE by Peter Tregear Born in Brockley, South London, Fritz Bennicke Hart (1874–1949) stands as one of the more extraordinary figures of the so-called English Musical Renaissance, all the more so because he remains so little known. His mother was a piano teacher from Cornwall and his father a travelling salesman of Irish ancestry born in East Anglia. The eldest of five, Hart was not encouraged to pursue a musical career as a child, but piano lessons from his mother were later complemented by the award of a choristership at Westminster Abbey, then under the direction of Frederick Bridge – ‘Westminster Bridge’, as he was inevitably nicknamed. A year earlier Bridge had been appointed professor of harmony and counterpoint at the newly constituted Royal College of Music and in 1893 Hart would join him there as a student of piano and organ. In addition, in the years between his tenure as a chorister and his enrolling at the RCM, Hart had been introduced to both the music and the aesthetic philosophy of Richard Wagner and had also become a regular and enthusiastic audience member of the Saturday orchestral concerts held at the Crystal Palace and the RCM. It seems Hart quickly became better known at the RCM for his ardent interest in opera and music drama than for his piano-playing. Indeed, Imogen Holst credits Hart with having introduced her father, Gustav, to Wagner.1 But unlike Holst and other contemporaries, such as Ralph Vaughan Williams, John Ireland, Samuel Coleridge- Taylor and William Hurlstone, Hart did not formally study composition. -

4969987-5449F5-5060113443267.Pdf

GUY ROPARTZ, FRENCH MASTER WITH BRETON ROOTS by Peter McCallum Composer, poet, conductor, novelist and administrator of remarkable energy, Joseph Guy Marie Ropartz (1864–1955) was born – in Guingamp, Côtes-du-Nord, more or less equidistant between Brest and St Malo – into a family of intellectual and artistic breadth and strong civic commitment to the culture and history of his native Brittany. These virtues shaped his music over a long, industrious and productive career, and each of them can be found in part in music included in this recording, which consists of two large-scale suites and a number of shorter pieces. Literary and narrative affinities pervade the two suites, particularly Dans l’ombre de la montagne, which also evokes folk-styles in some of its movements. His father, Sigismond Ropartz, was a lawyer, poet and enthusiastic chronicler of Breton history. After Sigismond’s death in 1879, Joseph studied in a Jesuit college at Vannes, where he learnt the bugle, French horn, double-bass and percussion and consolidated a profound Catholic faith. In deference to his mother’s wishes, he pursued training in law at Rennes, where he met Breton writer Louis Tiercelin and other artists interested in the Breton cultural revival. Ropartz joined the Breton Regionalist Union, a cultural organisation founded in 1898 and dedicated to preserving Breton culture and regional independence. He used the words of several Breton writers in musical settings, including Anatole Le Braz and Charles le Goffic. Although admitted to the bar in 1885, he does not seem to have ever practised law as a profession. -

TOCN0007DIGIBKLT.Pdf

FOUR HANDS FOR FRANCE Music for Piano Duet ERNEST CHAUSSON Sonatines pour quatre mains, Op. 2 (1879)* 20:53 Sonatine No. 1 in G major (1878) 6:24 1 I Gaîment 1:37 2 II Andante 2:59 3 III Finale 1:48 Sonatine No. 2 in D minor (1879) 14:29 4 I Mouvement de marche 4:52 5 II Variations sur un thème danois, transcrit par Niels Gade 5:44 6 III Rondeau-Allegretto 3:53 GUY ROPARTZ Petites Pièces (1903)* 25:30 Pour Gaud 7 No. 1 Andante 1:35 8 No. 2 Lento 1:31 9 No. 3 Allegretto 1:06 Sons de Cloches 10 No. 4 L’Angelus 3:18 11 No. 5 Le Glas 3:36 12 No. 6 Cloches du Soir 3:17 *** 13 No. 7 Choral 3:35 14 No. 8 Tristesse 1:37 15 No. 9 Intimité 2:24 16 No. 10 Par les Champs 3:31 2 JULES MASSENET Pièces pour le Piano à 4 Mains: 1re Suite, Op. 11 (1867)* 8:14 17 No. 1 Andante 2:55 18 No. 2 Allegretto quasi allegro 3:13 19 No. 3 Andante 2:06 CHARLES-VALENTIN ALKAN 20 Saltarelle, Op. 47 (1856) 7:03 CÉCILE CHAMINADE Pièces romantiques, Op. 55 (1890) 21 No. 1 Primavera 2:41 22 No. 3 Idylle arabe 2:43 23 No. 4 Sérénade d’automne 2:59 BENJAMIN GODARD Deux morceaux, Op. 137 (1893)* 2:45 24 No. 1 Pastorale mélancolique 1:39 25 No. 2 Marche villageoise 1:06 Stephanie McCallum (primo) and Erin Helyard (secondo) TT 72:51 Piano Erard 1853 * FIRST RECORDINGS 3 FOUR HANDS FOR FRANCE: MUSIC FOR PIANO DUET Stephanie McCallum Our starting point is in France. -

UNIVERSITY of LONDON THESIS J\Lv& AA

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree ^ Year Name of Author (_0 ^ 0 \ j\lV & A A COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting this thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962-1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975-1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

THE PIANO BOOK Pianos, Composers, Pianists, Recording Artists, Repertoire, Performing Practice, Analysis, Expression and Interpretation

THE PIANO BOOK pianos, composers, pianists, recording artists, repertoire, performing practice, analysis, expression and interpretation GERARD CARTER BEc LL B (Sydney) A Mus A (Piano Performing) WENSLEYDALE PRESS 2 THE PIANO BOOK 3 4 THE PIANO BOOK pianos, composers, pianists, recording artists, repertoire, performing practice, analysis, expression and interpretation GERARD CARTER BEc LL B (Sydney) A Mus A (Piano Performing) WENSLEYDALE PRESS 5 Published in 2008 by Wensleydale Press ABN 30 628 090 446 165/137 Victoria Street, Ashfield NSW 2131 Tel +61 2 9799 4226 Email [email protected] Designed and printed in Australia by Wensleydale Press, Ashfield Copyright © Gerard Carter 2008 All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (for example, a fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review) no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher. ISBN 978-0-9805441-0-7 This publication is sold and distributed on the understanding that the publisher and the author cannot guarantee that the contents of this publication are accurate, reliable, complete or up to date; they do not take responsibility for any loss or damage that happens as a result of using or relying on the contents of this publication and they are not giving advice in this publication. 6 INTRODUCTION ACCENT ACTION ALBERT D’ ALBERTI BASS ALKAN ALTENBURG AMERICAN TERMS ANSORGE -

Volume I | 1–47 Classic the Music You 100 Can’T Live Without

485 6245 4CDs | VOLUME I | 1–47 CLASSIC THE MUSIC YOU 100 CAN’T LIVE WITHOUT Music you can’t live without? Really? Maybe you’ve had the same thought. It’s all very well to love music, but it’s just noise, just a sound. Surely it’s a stretch to think that there’s music you can’t live without? I don’t agree. Music continues to be a unique force in human life. Sure, it’s just sound. But it’s sound that does so much. It amplifies our emotions – good and bad. It helps us feel close to those we love. And – crucially – it’s there for us when we’ve stopped feeling anything at all. When we’re numb. But what is the music you can’t live without? It’s a question we at ABC Classic asked you, and it was so wonderful to get your responses and hear your ideas. Thank you so much. We asked the question in May 2021, hot on the heels of a year that... well, you’ve read all the rhetoric, heard all the adjectives. Reading your comments and hearing your stories removed any doubt that music is an essential part of life – especially in these times. And you voted in numbers greater than ever before, showing your gratitude for this lifeblood we all share. The music you can’t live without. It ranges from the ancient, to that written in our own time, maybe by people you could bump into in the supermarket. But all of it so relevant and vital. -

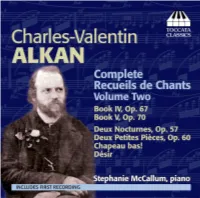

Toccata Classics TOCC0158 Notes

P CHARLES-VALENTIN ALKAN AND HIS RECUEILS DE CHANTS, VOLUME TWO by Peter McCallum Alkan’s ive books of Chants were written over a iteen-year period from 1857 to 1872 during his most artistically mature and productive phase, ater he emerged from a period of self-imposed social and artistic seclusion. In spite of their expressive variety, they are uniied both internally and over the complete ive- volume cycle, the ith book returning to some of the characteristics of the irst book, ending with a relective summary. Unlike the Opp. 35 and 39 studies in all the major and minor keys, they are not the alpha and omega of his achievement, but rather a more subtle and intricate map of the strands and range of his musical thought. It is a characteristic of all of Alkan’s best music that – although he works within the harmonic and tonal language, the range of genres and the stylistic parameters of the nineteenth century – he brings to each of them a singular personality deined by the sense of far-sighted clarity that comes with isolation. Such isolation inds beautiful, poignant and varied expression in the G minor Barcarolles that conclude each of the ive volumes of Chants. His sentimental moods (oten found in the E major pieces that open each set) are tinged with yearning and a sense that such comfort is for others; instead, as later with Mahler and Shostakovich, he is haunted by visions of parody, the banal and the grotesque. As seen sometimes in the third number of each set, each one a vigorous piece in A major, he oten uses these elements to create a keen edge to his artistic tone of voice. -

Publications for Stephanie Mccallum 2019 2018 2017 2016

Publications for Stephanie McCallum 2021 orchestral suite (Maurice Ravel), 4.Sonata for four hands McCallum, S. (2021). Wild Swans Suite. Adelaide Festival (Francis Poulenc). Stephanie McCallum and Erin Helyard in 2021: The Return. Ukaria Concert Hall, Ukaria Cultural Centre, Duo: Australia Piano World. Sydney Piano World, Chatswood, Adelaide, Australia: Adelaide Festival. Australia: Australia Piano World. 2019 2017 McCallum, S. (2019). Roy Agnew Piano Music, CD and all McCallum, S. (2017). Meter Symposium 2, Recital Hall West, online streaming services, London, United Kingdom: Toccata Sydney Conservatorium of Music, Sydney, Australia: Sydney Classics. Conservatorium of Music. McCallum, S. (2019). 1. Studium O 2. Musings on Le Dodo. McCallum, S. (2017). 1. Grande Sonata in E flat major Op.47: Chamber Works: Sideband Renaissance. Recital Hall West, I Allegro spiritoso, II Andantino quasi allegretto, III Adagio, IV Sydney, Australia: Sydney Conservatorium of Music and Finale:Allegro (Ignaz Moscheles) Sideband Ensemble. 2. Fantasia in F minor D.940: I Allegro molto moderato,II Largo, IIIScherzo: Allegro vivace, IV Finale: Allegro molto McCallum, S., Helyard, E. (2019). 1.Dolly Suite (Faure); 2. moderato (Franz Schubert). A Schubert Fantasy. Melba Hall / Suite Op.11 (Massenet); 3. Sons de cloches from Dix Petites Recital Hall West, Melbourne and Sydney, Australia: Pieces (Ropartz); 4. Trois Pieces Negres sue les touches Melbourne University / Sydney Conservatorium of Music. blanches (Lambert); 5.Primavera, Idylle Arabe and Serenade d'Automne from Six Romantic Pieces Op.55 (Chaminade); 6. McCallum, S. (2017). Decoding the Music Masterpieces: Saltarelle (Alkan). Perfume for two. Recital Hall West, Sydney Debussy's Clair de Lune. The Conversation. Conservatorium of Music, Sydney, Australia: Sydney McCallum, S., Queensland Symphony Orchestra, T. -

The Reception of Erik Satie's Gymnopédies

The Reception of Erik Satie’s Gymnopédies: Audience, Identity, and Commercialization Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Master of Arts in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Billie Eaves, M. M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Danielle Fosler‐Lussier, Advisor Arved Ashby Robert Sorton Copyright by Billie Eaves 2011 Abstract Erik Satie’s Trois Gymnopédies (1888) embody the aesthetic synthesis of high and low musical culture, which was the premise of artistic ventures at the Chat Noir, the cabaret frequented by Satie in the 1880s. The Gymnopédies maintained but softened distinct aesthetic boundaries by combining modernist and popular musical elements, making the pieces accessible to both artistic and bourgeois audiences. In subsequent performances, the popular musical elements more dominantly informed the identity of the works, and even though Claude Debussy’s 1896 orchestration of the Gymnopédies succeeded in elevating the status of the pieces, this prevailing perception led to aesthetic debates regarding the justification for including the works on concert programs. With the advent of recordings, the Gymnopédies attained a broader, less musically literate audience, and by the 1950s, commoditization and marketing campaigns targeting amateur audiences assigned new functions and meanings to the Gymnopédies that were wholly separate from intensive listening to the pieces as abstract, modernist music. For example, the pieces were marketed for such purposes as sleep, exercise, weddings, or light accompaniment to everyday activities. With experimental transcriptions, especially the arrangement by Blood, Sweat and Tears, Satie’s aesthetic identity was completely supplanted by influential performers.