The Diving Behaviour of the Manx Shearwater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Problems on Tristan Da Cunha Byj

28 Oryx Conservation Problems on Tristan da Cunha ByJ. H. Flint The author spent two years, 1963-65, as schoolmaster on Tristan da Cunha, during which he spent four weeks on Nightingale Island. On the main island he found that bird stocks were being depleted and the islanders taking too many eggs and young; on Nightingale, however, where there are over two million pairs of great shearwaters, the harvest of these birds could be greater. Inaccessible Island, which like Nightingale, is without cats, dogs or rats, should be declared a wildlife sanctuary. Tl^HEN the first permanent settlers came to Tristan da Cunha in " the early years of the nineteenth century they found an island rich in bird and sea mammal life. "The mountains are covered with Albatross Mellahs Petrels Seahens, etc.," wrote Jonathan Lambert in 1811, and Midshipman Greene, who stayed on the island in 1816, recorded in his diary "Sea Elephants herding together in immense numbers." Today the picture is greatly changed. A century and a half of human habitation has drastically reduced the larger, edible species, and the accidental introduction of rats from a shipwreck in 1882 accelerated the birds' decline on the main island. Wood-cutting, grazing by domestic stock and, more recently, fumes from the volcano have destroyed much of the natural vegetation near the settlement, and two bird subspecies, a bunting and a flightless moorhen, have become extinct on the main island. Curiously, one is liable to see more birds on the day of arrival than in several weeks ashore. When I first saw Tristan from the decks of M.V. -

Puffinus Gravis (Great Shearwater)

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Puffinus gravis (Great Shearwater) Priority 3 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Procellariiformes (Tubenoses) Family: Procellariidae (Fulmers, Petrels, And Shearwaters) General comments: Status seems secure though limited data Species Conservation Range Maps for Great Shearwater: Town Map: Puffinus gravis_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Puffinus gravis_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: North American Waterbird Conservation Plan: High Concern United States Birds of Conservation Concern: Bird of Conservation Concern in Bird Conservation Regions 14 and/or 30: Yes High Climate Change Vulnerability: NA Understudied rare taxa: NA Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to Great Shearwater: Formation Name Cliff & Rock Macrogroup Name Rocky Coast Formation Name Subtidal Macrogroup Name Subtidal Pelagic (Water Column) Habitat System Name: Offshore **Primary Habitat** Stressors Assigned to Great Shearwater: No Stressors Currently Assigned to Great Shearwater or other Priority 3 SGCN. Species Level Conservation Actions Assigned to Great Shearwater: No Species Specific Conservation Actions Currently Assigned to Great Shearwater or other Priority 3 SGCN. Guild Level Conservation Actions: This Species is currently not attributed to a guild. -

Bugoni 2008 Phd Thesis

ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF ALBATROSSES AND PETRELS AT SEA OFF BRAZIL Leandro Bugoni Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, at the Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow. July 2008 DECLARATION I declare that the work described in this thesis has been conducted independently by myself under he supervision of Professor Robert W. Furness, except where specifically acknowledged, and has not been submitted for any other degree. This study was carried out according to permits No. 0128931BR, No. 203/2006, No. 02001.005981/2005, No. 023/2006, No. 040/2006 and No. 1282/1, all granted by the Brazilian Environmental Agency (IBAMA), and International Animal Health Certificate No. 0975-06, issued by the Brazilian Government. The Scottish Executive - Rural Affairs Directorate provided the permit POAO 2007/91 to import samples into Scotland. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I was very lucky in having Prof. Bob Furness as my supervisor. He has been very supportive since before I had arrived in Glasgow, greatly encouraged me in new initiatives I constantly brought him (and still bring), gave me the freedom I needed and reviewed chapters astonishingly fast. It was a very productive professional relationship for which I express my gratitude. Thanks are also due to Rona McGill who did a great job in analyzing stable isotopes and teaching me about mass spectrometry and isotopes. Kate Griffiths was superb in sexing birds and explaining molecular methods again and again. Many people contributed to the original project with comments, suggestions for the chapters, providing samples or unpublished information, identifyiyng fish and squids, reviewing parts of the thesis or helping in analysing samples or data. -

Teesmouth Bird Club Newsletter

No.23 Autumn 2002 Teesmouth Bird Club Newsletter Editor: M.J.Gee, Technical Adviser: R.Hammond, Distributor: C. Sharp Address: All correspondence to 21 Gladstone Street, Hartlepool, TS24 0PE. Email: [email protected] Newsletter Web-site: http://www.watsonpress.co.uk/tbc Thanks to the contributors to this issue:- Chris Sharp; Alan Wheeldon; Mike Leakey; Rob Little; Brian Clasper. All unsolicited copy will be most welcome, ideally sent by email, or on 3.5" computer disk, using word processing software, but typed and handwritten copy is equally acceptable. Any topic concerned with birds or the local environment is grist to the mill. MONTHLY SUMMARY by Chris Sharp July 19th. It was generally elusive occasionally being seen on Seal Sands and at high Tide on Greenabella Marsh. A single Little An Osprey was at Scaling Dam (2nd – 3rd). Passage waders Egret remained on the North Tees Marshes all month. A northerly began to build up in numbers as usual from early in the month blow on 10th saw 3 Sooties and 20 Bonxies off Hartlepool. with a few Wood Sandpiper and Greenshank on Dormans Pool th being the highlight during the first 10 days. The 12th though Another Red-backed Shrike was found at Zinc Works Road (12 - 14th). Marsh Harriers increased to 3 at Dormans Pool around mid- produced a Temminck’s Stint and a Pectoral Sandpiper on th Greatham Saline Lagoon. The following morning an adult month. A Bittern was on Dormans Pool on 18 and remained into White-rumped Sandpiper was around Greatham Creek/Cowpen September, being occasionally seen in flight. -

Longline Fishing at Tristan Da Cunha: Impacts on Seabirds

2000 Tristan da Cunha longlining 49 Longline fishing at Tristan da Cunha: impacts on seabirds Lijnvisserij bij Tristan da Cunha en de gevolgen voor zeevogels 1, 1 Norman Glass Ian Lavarello James+P. Glass 2 2 &Peter+G. Ryan 1 Natural Resources Department, Tristan da Cunha, South Atlantic Ocean (via 2 Cape Town): email: [email protected]; Percy FitzPatrick Institute, University ofCape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa; email: [email protected] Tristan da Cunha and Islands in the central South Atlantic Ocean Gough support globally importantseabird populations. Two longlinefisheries occur within Tristan’s Exclusive Economic Zone: a pelagic fishery for tunas and a demersal fishery for bluefish and alfoncino. Fishery observers have accompanied all three licensed demersal cruises. Despite attracting considerable numbers of birds and setting lines during the 0.001 day, only onebird (a Great Sheawater Puffinus gravis) was killed (mortality rate birds per 1000 hooks). By comparison, the pelagic fishery for tuna, which exceeds demersal has much Observations aboard fishing effort, probably a greater impact. one killed vessel in mid-winter suggest a bycatch rate of>1 bird per 1000 hooks; this could be even higher in summer when more birds are breeding at the islands. Stricter regulations are requiredforpelagic vessels, including routineplacing of observers on board. The gravest threat posed by longlinefishing to Tristan’s seabirds comes from in vesselsfishing illegally Tristan waters, as well as vessels in international waters that is do not use basic mitigation measures. There a pressing need for betterpolicing of Tristan’s waters. Glass N., Lavarello I., Glass J.P. -

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2016-C No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark 02 06 Recognize Lilian’s Meadowlark Sturnella lilianae as a separate species from S. magna 03 20 Change the English name of Euplectes franciscanus to Northern Red Bishop 04 25 Transfer Sandhill Crane Grus canadensis to Antigone 05 29 Add Rufous-necked Wood-Rail Aramides axillaris to the U.S. list 06 31 Revise our higher-level linear sequence as follows: (a) Move Strigiformes to precede Trogoniformes; (b) Move Accipitriformes to precede Strigiformes; (c) Move Gaviiformes to precede Procellariiformes; (d) Move Eurypygiformes and Phaethontiformes to precede Gaviiformes; (e) Reverse the linear sequence of Podicipediformes and Phoenicopteriformes; (f) Move Pterocliformes and Columbiformes to follow Podicipediformes; (g) Move Cuculiformes, Caprimulgiformes, and Apodiformes to follow Columbiformes; and (h) Move Charadriiformes and Gruiformes to precede Eurypygiformes 07 45 Transfer Neocrex to Mustelirallus 08 48 (a) Split Ardenna from Puffinus, and (b) Revise the linear sequence of species of Ardenna 09 51 Separate Cathartiformes from Accipitriformes 10 58 Recognize Colibri cyanotus as a separate species from C. thalassinus 11 61 Change the English name “Brush-Finch” to “Brushfinch” 12 62 Change the English name of Ramphastos ambiguus 13 63 Split Plain Wren Cantorchilus modestus into three species 14 71 Recognize the genus Cercomacroides (Thamnophilidae) 15 74 Split Oceanodroma cheimomnestes and O. socorroensis from Leach’s Storm- Petrel O. leucorhoa 2016-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 453 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark There are a dizzying number of larks (Alaudidae) worldwide and a first-time visitor to Africa or Mongolia might confront 10 or more species across several genera. -

Classic Versus Metabarcoding Approaches for the Diet Study of a Remote Island Endemic Gecko

Questioning the proverb `more haste, less speed': classic versus metabarcoding approaches for the diet study of a remote island endemic gecko Vanessa Gil1,*, Catarina J. Pinho2,3,*, Carlos A.S. Aguiar1, Carolina Jardim4, Rui Rebelo1 and Raquel Vasconcelos2 1 Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal 2 CIBIO, Centro de Investigacão¸ em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, InBIO Laboratório Associado, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal 3 Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal 4 Instituto das Florestas e Conservacão¸ da Natureza IP-RAM, Funchal, Madeira, Portugal * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Dietary studies can reveal valuable information on how species exploit their habitats and are of particular importance for insular endemics conservation as these species present higher risk of extinction. Reptiles are often neglected in island systems, principally the ones inhabiting remote areas, therefore little is known on their ecological networks. The Selvagens gecko Tarentola (boettgeri) bischoffi, endemic to the remote and integral reserve of Selvagens Archipelago, is classified as Vulnerable by the Portuguese Red Data Book. Little is known about this gecko's ecology and dietary habits, but it is assumed to be exclusively insectivorous. The diet of the continental Tarentola species was already studied using classical methods. Only two studies have used next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques for this genus thus far, and very few NGS studies have been employed for reptiles in general. Considering the lack of information on its diet Submitted 10 April 2019 and the conservation interest of the Selvagens gecko, we used morphological and Accepted 22 October 2019 Published 2 January 2020 DNA metabarcoding approaches to characterize its diet. -

Brookline Bird Club Extreme Pelagic 22 -‐ 23 August 2015 by Luke Seitz

Brookline Bird Club Extreme Pelagic 22 - 23 August 2015 by Luke Seitz and Jeremiah Trimble [all photos by J. Trimble unless noted] Map of trip – 22 – 23 August 2015 Complete checklists will be included at the end of the narrative. This report would not have been possible without the combined efforts of all leaders on board! Thank you Nick Bonomo, Julian Hough, Luke Seitz and Doug Gochfeld! Here can be found a narrative of the Brookline Bird Club Extreme Pelagic that took place this past weekend (August 22-13). As has already been publicly advertised, it was a hugely successful trip and will go down as one of, if not the, best trip we have ever run. The trip began in a moderate downpour at the docks in Hyannis Harbor. This did not dampen the excitement of those on board and before long we were underway under clearing skies. Hyannis Harbor revealed a good diversity of terns including Black, Forster's, and Roseate Terns. The crossing of Nantucket Sound was uneventful, as was much of Nantucket Shoals. The Shoals did provide us with some of our first true pelagics including Cory's Shearwaters, Great Shearwaters, and Red- necked Phalaropes. There were surely many more birds but the Shoals, as can often be the case, were shrouded in a thick fog for almost our entire passage of this shallow area. Red-necked Phalarope Our first major excitement occurred in that fog near the southern edge of Nantucket Shoals, when a South Polar Skua was spotted sitting on the water directly ahead of the Helen H. -

Conservation Status of New Zealand Birds, 2008

Notornis, 2008, Vol. 55: 117-135 117 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. Conservation status of New Zealand birds, 2008 Colin M. Miskelly* Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand [email protected] JOHN E. DOWDING DM Consultants, P.O. Box 36274, Merivale, Christchurch 8146, New Zealand GRAEME P. ELLIOTT Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, Private Bag 5, Nelson 7042, New Zealand RODNEY A. HITCHMOUGH RALPH G. POWLESLAND HUGH A. ROBERTSON Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand PAUL M. SAGAR National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 8602, Christchurch 8440, New Zealand R. PAUL SCOFIELD Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8001, New Zealand GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand Abstract An appraisal of the conservation status of the post-1800 New Zealand avifauna is presented. The list comprises 428 taxa in the following categories: ‘Extinct’ 20, ‘Threatened’ 77 (comprising 24 ‘Nationally Critical’, 15 ‘Nationally Endangered’, 38 ‘Nationally Vulnerable’), ‘At Risk’ 93 (comprising 18 ‘Declining’, 10 ‘Recovering’, 17 ‘Relict’, 48 ‘Naturally Uncommon’), ‘Not Threatened’ (native and resident) 36, ‘Coloniser’ 8, ‘Migrant’ 27, ‘Vagrant’ 130, and ‘Introduced and Naturalised’ 36. One species was assessed as ‘Data Deficient’. The list uses the New Zealand Threat Classification System, which provides greater resolution of naturally uncommon taxa typical of insular environments than the IUCN threat ranking system. New Zealand taxa are here ranked at subspecies level, and in some cases population level, when populations are judged to be potentially taxonomically distinct on the basis of genetic data or morphological observations. -

Proposals 2018-C

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-C 1 March 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae 02 10 Split Yellow Warbler (Setophaga petechia) into two species 03 25 Revise the classification and linear sequence of the Tyrannoidea (with amendment) 04 39 Split Cory's Shearwater (Calonectris diomedea) into two species 05 42 Split Puffinus boydi from Audubon’s Shearwater P. lherminieri 06 48 (a) Split extralimital Gracula indica from Hill Myna G. religiosa and (b) move G. religiosa from the main list to Appendix 1 07 51 Split Melozone occipitalis from White-eared Ground-Sparrow M. leucotis 08 61 Split White-collared Seedeater (Sporophila torqueola) into two species (with amendment) 09 72 Lump Taiga Bean-Goose Anser fabalis and Tundra Bean-Goose A. serrirostris 10 78 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 11 87 Transfer Loxigilla portoricensis and L. violacea to Melopyrrha 12 90 Split Gray Nightjar Caprimulgus indicus into three species, recognizing (a) C. jotaka and (b) C. phalaena 13 93 Split Barn Owl (Tyto alba) into three species 14 99 Split LeConte’s Thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei) into two species 15 105 Revise generic assignments of New World “grassland” sparrows 1 2018-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee pp. 87-105 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae Background: Our current linear sequence of the Accipitridae, which places all the kites at the beginning, followed by the harpy and sea eagles, accipiters and harriers, buteonines, and finally the booted eagles, follows the revised Peters classification of the group (Stresemann and Amadon 1979). -

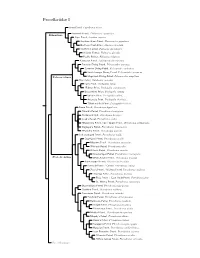

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

British Birds

British Birds Vol. 56 No. 6 JUNE 1963 The distribution of the Sooty Shearwater around the British Isles By J. H. Phillips RECENT RECORDS of the Sooty Shearwater (JProcellaria grised) from under-watched parts of the British coast can now lead us to an import ant reassessment of the status of this species. Its classification as a 'rather scarce visitor' in The Handbook (Witherby et al. 1940) and as an 'irregular visitor' in the B.O.U. Check-list (1952) was adequate accord ing to the records existing at those dates, but is by no means consistent with our present knowledge. This paper gives the main records of the species that have been made in the north-east Atlantic: the relation of its records and movements to oceanographic and meteorological conditions is being discussed elsewhere (Phillips 1963). The Sooty Shearwater is widely distributed over the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Birds spending the non-breeding season (May to September) in the Atlantic, probably numbering only some tens of thousands, are derived from large colonies off Cape Horn, and from the Falkland Islands. Kuroda (1957) has discussed the concept of a circular migration of the Tubinares around the world oceans, and it seems likely that Sooty Shearwaters reach the British Isles after moving up the east coast of North America and crossing the Atlantic between 450 and 6o°N. It is possible that this crossing is made only by those birds not breeding in the succeeding season. MONTHLY DISTRIBUTION OF RECORDS Fig. i shows the known distribution of the Sooty Shearwater around the British Isles.