Longline Fishing at Tristan Da Cunha: Impacts on Seabirds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Problems on Tristan Da Cunha Byj

28 Oryx Conservation Problems on Tristan da Cunha ByJ. H. Flint The author spent two years, 1963-65, as schoolmaster on Tristan da Cunha, during which he spent four weeks on Nightingale Island. On the main island he found that bird stocks were being depleted and the islanders taking too many eggs and young; on Nightingale, however, where there are over two million pairs of great shearwaters, the harvest of these birds could be greater. Inaccessible Island, which like Nightingale, is without cats, dogs or rats, should be declared a wildlife sanctuary. Tl^HEN the first permanent settlers came to Tristan da Cunha in " the early years of the nineteenth century they found an island rich in bird and sea mammal life. "The mountains are covered with Albatross Mellahs Petrels Seahens, etc.," wrote Jonathan Lambert in 1811, and Midshipman Greene, who stayed on the island in 1816, recorded in his diary "Sea Elephants herding together in immense numbers." Today the picture is greatly changed. A century and a half of human habitation has drastically reduced the larger, edible species, and the accidental introduction of rats from a shipwreck in 1882 accelerated the birds' decline on the main island. Wood-cutting, grazing by domestic stock and, more recently, fumes from the volcano have destroyed much of the natural vegetation near the settlement, and two bird subspecies, a bunting and a flightless moorhen, have become extinct on the main island. Curiously, one is liable to see more birds on the day of arrival than in several weeks ashore. When I first saw Tristan from the decks of M.V. -

Puffinus Gravis (Great Shearwater)

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Puffinus gravis (Great Shearwater) Priority 3 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Procellariiformes (Tubenoses) Family: Procellariidae (Fulmers, Petrels, And Shearwaters) General comments: Status seems secure though limited data Species Conservation Range Maps for Great Shearwater: Town Map: Puffinus gravis_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Puffinus gravis_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: North American Waterbird Conservation Plan: High Concern United States Birds of Conservation Concern: Bird of Conservation Concern in Bird Conservation Regions 14 and/or 30: Yes High Climate Change Vulnerability: NA Understudied rare taxa: NA Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to Great Shearwater: Formation Name Cliff & Rock Macrogroup Name Rocky Coast Formation Name Subtidal Macrogroup Name Subtidal Pelagic (Water Column) Habitat System Name: Offshore **Primary Habitat** Stressors Assigned to Great Shearwater: No Stressors Currently Assigned to Great Shearwater or other Priority 3 SGCN. Species Level Conservation Actions Assigned to Great Shearwater: No Species Specific Conservation Actions Currently Assigned to Great Shearwater or other Priority 3 SGCN. Guild Level Conservation Actions: This Species is currently not attributed to a guild. -

Bugoni 2008 Phd Thesis

ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF ALBATROSSES AND PETRELS AT SEA OFF BRAZIL Leandro Bugoni Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, at the Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow. July 2008 DECLARATION I declare that the work described in this thesis has been conducted independently by myself under he supervision of Professor Robert W. Furness, except where specifically acknowledged, and has not been submitted for any other degree. This study was carried out according to permits No. 0128931BR, No. 203/2006, No. 02001.005981/2005, No. 023/2006, No. 040/2006 and No. 1282/1, all granted by the Brazilian Environmental Agency (IBAMA), and International Animal Health Certificate No. 0975-06, issued by the Brazilian Government. The Scottish Executive - Rural Affairs Directorate provided the permit POAO 2007/91 to import samples into Scotland. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I was very lucky in having Prof. Bob Furness as my supervisor. He has been very supportive since before I had arrived in Glasgow, greatly encouraged me in new initiatives I constantly brought him (and still bring), gave me the freedom I needed and reviewed chapters astonishingly fast. It was a very productive professional relationship for which I express my gratitude. Thanks are also due to Rona McGill who did a great job in analyzing stable isotopes and teaching me about mass spectrometry and isotopes. Kate Griffiths was superb in sexing birds and explaining molecular methods again and again. Many people contributed to the original project with comments, suggestions for the chapters, providing samples or unpublished information, identifyiyng fish and squids, reviewing parts of the thesis or helping in analysing samples or data. -

Teesmouth Bird Club Newsletter

No.23 Autumn 2002 Teesmouth Bird Club Newsletter Editor: M.J.Gee, Technical Adviser: R.Hammond, Distributor: C. Sharp Address: All correspondence to 21 Gladstone Street, Hartlepool, TS24 0PE. Email: [email protected] Newsletter Web-site: http://www.watsonpress.co.uk/tbc Thanks to the contributors to this issue:- Chris Sharp; Alan Wheeldon; Mike Leakey; Rob Little; Brian Clasper. All unsolicited copy will be most welcome, ideally sent by email, or on 3.5" computer disk, using word processing software, but typed and handwritten copy is equally acceptable. Any topic concerned with birds or the local environment is grist to the mill. MONTHLY SUMMARY by Chris Sharp July 19th. It was generally elusive occasionally being seen on Seal Sands and at high Tide on Greenabella Marsh. A single Little An Osprey was at Scaling Dam (2nd – 3rd). Passage waders Egret remained on the North Tees Marshes all month. A northerly began to build up in numbers as usual from early in the month blow on 10th saw 3 Sooties and 20 Bonxies off Hartlepool. with a few Wood Sandpiper and Greenshank on Dormans Pool th being the highlight during the first 10 days. The 12th though Another Red-backed Shrike was found at Zinc Works Road (12 - 14th). Marsh Harriers increased to 3 at Dormans Pool around mid- produced a Temminck’s Stint and a Pectoral Sandpiper on th Greatham Saline Lagoon. The following morning an adult month. A Bittern was on Dormans Pool on 18 and remained into White-rumped Sandpiper was around Greatham Creek/Cowpen September, being occasionally seen in flight. -

Brookline Bird Club Extreme Pelagic 22 -‐ 23 August 2015 by Luke Seitz

Brookline Bird Club Extreme Pelagic 22 - 23 August 2015 by Luke Seitz and Jeremiah Trimble [all photos by J. Trimble unless noted] Map of trip – 22 – 23 August 2015 Complete checklists will be included at the end of the narrative. This report would not have been possible without the combined efforts of all leaders on board! Thank you Nick Bonomo, Julian Hough, Luke Seitz and Doug Gochfeld! Here can be found a narrative of the Brookline Bird Club Extreme Pelagic that took place this past weekend (August 22-13). As has already been publicly advertised, it was a hugely successful trip and will go down as one of, if not the, best trip we have ever run. The trip began in a moderate downpour at the docks in Hyannis Harbor. This did not dampen the excitement of those on board and before long we were underway under clearing skies. Hyannis Harbor revealed a good diversity of terns including Black, Forster's, and Roseate Terns. The crossing of Nantucket Sound was uneventful, as was much of Nantucket Shoals. The Shoals did provide us with some of our first true pelagics including Cory's Shearwaters, Great Shearwaters, and Red- necked Phalaropes. There were surely many more birds but the Shoals, as can often be the case, were shrouded in a thick fog for almost our entire passage of this shallow area. Red-necked Phalarope Our first major excitement occurred in that fog near the southern edge of Nantucket Shoals, when a South Polar Skua was spotted sitting on the water directly ahead of the Helen H. -

Conservation Status of New Zealand Birds, 2008

Notornis, 2008, Vol. 55: 117-135 117 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. Conservation status of New Zealand birds, 2008 Colin M. Miskelly* Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand [email protected] JOHN E. DOWDING DM Consultants, P.O. Box 36274, Merivale, Christchurch 8146, New Zealand GRAEME P. ELLIOTT Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, Private Bag 5, Nelson 7042, New Zealand RODNEY A. HITCHMOUGH RALPH G. POWLESLAND HUGH A. ROBERTSON Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand PAUL M. SAGAR National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 8602, Christchurch 8440, New Zealand R. PAUL SCOFIELD Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8001, New Zealand GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand Abstract An appraisal of the conservation status of the post-1800 New Zealand avifauna is presented. The list comprises 428 taxa in the following categories: ‘Extinct’ 20, ‘Threatened’ 77 (comprising 24 ‘Nationally Critical’, 15 ‘Nationally Endangered’, 38 ‘Nationally Vulnerable’), ‘At Risk’ 93 (comprising 18 ‘Declining’, 10 ‘Recovering’, 17 ‘Relict’, 48 ‘Naturally Uncommon’), ‘Not Threatened’ (native and resident) 36, ‘Coloniser’ 8, ‘Migrant’ 27, ‘Vagrant’ 130, and ‘Introduced and Naturalised’ 36. One species was assessed as ‘Data Deficient’. The list uses the New Zealand Threat Classification System, which provides greater resolution of naturally uncommon taxa typical of insular environments than the IUCN threat ranking system. New Zealand taxa are here ranked at subspecies level, and in some cases population level, when populations are judged to be potentially taxonomically distinct on the basis of genetic data or morphological observations. -

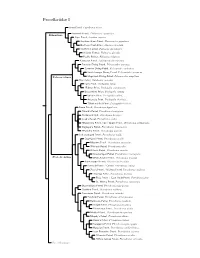

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

British Birds

British Birds Vol. 56 No. 6 JUNE 1963 The distribution of the Sooty Shearwater around the British Isles By J. H. Phillips RECENT RECORDS of the Sooty Shearwater (JProcellaria grised) from under-watched parts of the British coast can now lead us to an import ant reassessment of the status of this species. Its classification as a 'rather scarce visitor' in The Handbook (Witherby et al. 1940) and as an 'irregular visitor' in the B.O.U. Check-list (1952) was adequate accord ing to the records existing at those dates, but is by no means consistent with our present knowledge. This paper gives the main records of the species that have been made in the north-east Atlantic: the relation of its records and movements to oceanographic and meteorological conditions is being discussed elsewhere (Phillips 1963). The Sooty Shearwater is widely distributed over the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Birds spending the non-breeding season (May to September) in the Atlantic, probably numbering only some tens of thousands, are derived from large colonies off Cape Horn, and from the Falkland Islands. Kuroda (1957) has discussed the concept of a circular migration of the Tubinares around the world oceans, and it seems likely that Sooty Shearwaters reach the British Isles after moving up the east coast of North America and crossing the Atlantic between 450 and 6o°N. It is possible that this crossing is made only by those birds not breeding in the succeeding season. MONTHLY DISTRIBUTION OF RECORDS Fig. i shows the known distribution of the Sooty Shearwater around the British Isles. -

The First Confirmed Record of Great Shearwater Puffinus Gravis for British Columbia

44 Brief notes Smith, J., C.J. Farmer, S.W. Hoffman, G.S. Kaltenecker, K.Z. Wahl, T.R., B. Tweit, and S.G. Mlodinow. 2005. Birds of Woodruff and P.F. Sherrington. 2008b. Trends in autumn Washington: status and distribution. Oregon State counts of migratory raptors in western North America. University Press, Corvallis, Ore. p. 217-252 in K.L. Bildstein, J.P. Smith and E. Ruelas I. Wheeler, B.K. 2003. Raptors of western North America. (eds). The State of North American Birds of Prey. Series Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. in Ornithology, no. 3. American Ornithologists’ Union Wilbur, S.R. 1973. The Red-shouldered Hawk in the western and Nuttall Ornithological Club, Cambridge, Mass. United States. Western Birds 4(1):15. The first confirmed record of Great Shearwater Puffinus gravis for British Columbia Norman Ratcliffe1 and Christophe Barbraud2 1British Antarctic Survey, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge, UK. CB3 0ET; e-mail [email protected] 2Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chize´, CNRS UPR 1934, 79360 Villiers en Bois, France. Abstract: A Great Shearwater (Puffinus gravis), observed and photographed 52 km WSW of Tofino, B.C., on 2010 September 13, represents the first confirmed sighting of this species for the province. Key words: British Columbia, extralimital occurrence, Great Shearwater, Puffinus gravis On Monday 2010 September 13, we embarked on a pelagic trip from Tofino, Vancouver Island, B.C., in a vessel operated by “the Whale Centre”. We steamed to a canyon at the shelf break at 48º 57’N 126º35’W, 52 km WSW of Tofino, where several trawlers were operating. -

Shearwatersrefs V1.10.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2018 & 2019 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Grateful thanks to Ashley Fisher (www.scillypelagics.com) for the cover images. All images © the photographer. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2017. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 7.3 accessed August 2017]). Version Version 1.10 (January 2018). Cover Main image: Great Shearwater. At sea 3’ SW of the Bishop Rock, Isles of Scilly. 8th August 2009. Picture by Ashley Fisher. Vignette: Sooty Shearwater. At sea off the Isles of Scilly. 14th August 2009. Picture by Ashley Fisher. Species Page No. Audubon's Shearwater [Puffinus lherminieri] 34 Balearic Shearwater [Puffinus mauretanicus] 28 Bannerman's Shearwater [Puffinus bannermani] 37 Barolo Shearwater [Puffinus baroli] 38 Black-vented Shearwater [Puffinus opisthomelas] 30 Boyd's Shearwater [Puffinus boydi] 38 Bryan's Shearwater [Puffinus bryani] 29 Buller's Shearwater [Ardenna bulleri] 15 Cape Verde Shearwater [Calonectris edwardsii] 12 Christmas Island Shearwater [Puffinus nativitatis] 23 Cory's Shearwater [Calonectris borealis] 9 Flesh-footed Shearwater [Ardenna carneipes] 21 Fluttering -

Threats to Seabirds: a Global Assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P

1 Threats to seabirds: a global assessment 2 3 4 Authors: Maria P. Dias1*, Rob Martin1, Elizabeth J. Pearmain1, Ian J. Burfield1, Cleo Small2, Richard A. 5 Phillips3, Oliver Yates4, Ben Lascelles1, Pablo Garcia Borboroglu5, John P. Croxall1 6 7 8 Affiliations: 9 1 - BirdLife International. The David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK 10 2 - BirdLife International Marine Programme, RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy, SG19 2DL 11 3 – British Antarctic Survey. Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, 12 Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 13 4 – Centre for the Environment, Fishery and Aquaculture Science, Pakefield Road, Lowestoft, NR33, UK 14 5 - Global Penguin Society, University of Washington and CONICET Argentina. Puerto Madryn U9120, 15 Chubut, Argentina 16 * Corresponding author: Maria Dias, [email protected]. BirdLife International. The David 17 Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK. Phone: +44 (0)1223 747540 18 19 20 Acknowledgements 21 We are very grateful to Bartek Arendarczyk, Sophie Bennett, Ricky Hibble, Eleanor Miller and Amy 22 Palmer-Newton for assisting with the bibliographic review. We thank Rachael Alderman, Pep Arcos, 23 Jonathon Barrington, Igor Debski, Peter Hodum, Gustavo Jimenez, Jeff Mangel, Ken Morgan, Paul Sagar, 24 Peter Ryan, and other members of the ACAP PaCSWG, and the members of IUCN SSC Penguin Specialist 25 Group (Alejandro Simeone, Andre Chiaradia, Barbara Wienecke, Charles-André Bost, Lauren Waller, Phil 26 Trathan, Philip Seddon, Susie Ellis, Tom Schneider and Dee Boersma) for reviewing threats to selected 27 species. We thank also Andy Symes, Rocio Moreno, Stuart Butchart, Paul Donald, Rory Crawford, 28 Tammy Davies, Ana Carneiro and Tris Allinson for fruitful discussions and helpful comments on earlier 29 versions of the manuscript. -

Trans-Equatorial Migration and Habitat Use by Sooty Shearwaters Puffinus Griseus from the South Atlantic During the Nonbreeding Season

Vol. 449: 277–290, 2012 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published March 8 doi: 10.3354/meps09538 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Trans-equatorial migration and habitat use by sooty shearwaters Puffinus griseus from the South Atlantic during the nonbreeding season April Hedd1,*, William A. Montevecchi1, Helen Otley2, Richard A. Phillips3, David A. Fifield1 1Cognitive and Behavioural Ecology Program, Psychology Dept., Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland A1C 3C9, Canada 2Environmental Planning Dept., Falkland Islands Government, Stanley, Falkland Islands FFI 1ZZ, UK 3British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK ABSTRACT: The distributions of many marine birds, particularly those that are highly pelagic, remain poorly known outside the breeding period. Here we use geolocator-immersion loggers to study trans-equatorial migration, activity patterns and habitat use of sooty shearwaters Puffinus griseus from Kidney Island, Falkland Islands, during the 2008 and 2009 nonbreeding seasons. Between mid March and mid April, adults commenced a ~3 wk, >15 000 km northward migration. Most birds (72%) staged in the northwest Atlantic from late April to early June in deep, warm and relatively productive waters west of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (~43−55° N, ~32−43° W) in what we speculate is an important moulting area. Primary feathers grown during the moult had average δ15N and δ13C values of 13.4 ± 1.8‰ and −18.9 ± 0.5‰, respectively. Shearwaters moved into shal- low, warm continental shelf waters of the eastern Canadian Grand Bank in mid June and resided there for the northern summer. Migrant Puffinus shearwaters from the southern hemisphere are the primary avian consumers of fish within this ecosystem in summer.