Mavis Staples 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Area Artisans to Create Masterpieces, Combat AIDS for Detroit's First

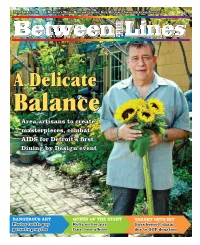

PRIDESOURCE.COM MICHIGAN’S WEEKLY NEWS FOR LESBIANS, GAYS, BISEXUALS, TRANSGENDERS AND FRIENDS 1831 08.05.10 A Delicate Balance Area artisans to create masterpieces, combat AIDS for Detroit’s first Dining by Design event DANGEROUS ART QUEEN OF THE NIGHT TARGET GETS HIT Photos tackle gay Kelis on her gay Gays boycott chain parenting myths fans, new album due to GOP donation 2 Between The Lines • August 5, 2010 August 5, 2010 Vol. 1831 • Issue 673 Publishers Susan Horowitz Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi Associate News Editor Jessica Carreras Arts & Theater Editor 12 19 21 34 Donald V. Calamia Editorial Intern 13 NJ Supreme Court rejects 25 Curtain Calls Lucy Hough News same-sex marriage case Reviews of “The Last Night of Ballyhoo” and Contributing Writers Lawsuit filed over whether state’s civil union “Herstory Repeats Herself: A Trilogy in 3-D” Charles Alexander, Paul Berg, Wayne Besen, 5 Between Ourselves law provides equal treatment for gay couples D.A. Blackburn, Dave Brousseau, Tony O’Rourke-Quintana Michelle E. Brown, John Corvino, 26 Happenings Jack Fertig, Joan Hilty, Lisa Keen, Jim Larkin, Jason A. Michael, 14 International News Briefs Anthony Paull, Crystal Proxmire, 6 A Delicate Balance Gay weddings begin in Argentina Bob Roehr, Gregg Shapiro, Jody Valley, Beauty of art meets darkness of disease Rear View D’Anne Witkowski, Imani Williams at Detroit’s first Dining by Design HIV/AIDS Rex Wockner, Dan Woog fundraiser Opinions Contributing Photographer 28 Dear Jody Andrew -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. January 13, 2020 to Sun. January 19, 2020

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. January 13, 2020 to Sun. January 19, 2020 Monday January 13, 2020 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT The Top Ten Revealed Tom Green Live Epic Songs of ‘73 - Find out which epic songs of ‘73 make our list as rock experts like Eddie Andrew Dice Clay - It’s a reunion of the true bad boys of comedy as actor and legendary stand-up Money, Lita Ford, Clem Burke (Blondie), Caleb Quaye (Elton John) and Jack Russell (Jack Russell’s comedian Andrew Dice Clay reconnects with his running mate Tom for a no-holds-barred discus- Great White) count us down! sion of life, show-biz, and whatever else pops up. 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT The Day The Rock Star Died Classic Albums Michael Jackson - Michael Jackson was a singer, songwriter, dancer and known simply as “The Phil Collins: Face Value - The program includes several previously unseen performances as well as King of Pop.” His contributions to music, dance, and highly publicized personal life made him a rare home movies of the studio sessions where Phil Collins worked closely with Hugh Padgham global figure in popular culture for over four decades. and the Earth, Wind & Fire horn section. Featuring the classic ‘In The Air Tonight,’ ‘Behind The Lines,’ ‘Please Don’t Ask,’ ‘I Missed Again’ and ‘This Must Be Love.’ 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT The Ronnie Wood Show 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Bobby Gillespie - Joining Ronnie this week is lead singer and founding member of Primal Rock Legends Scream, Scottish-born Bobby Gillespie. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. April 22, 2019 to Sun. April 28, 2019 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. April 22, 2019 to Sun. April 28, 2019 Monday April 22, 2019 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Rock Legends Smart Travels Europe Amy Winehouse - Despite living a tragically short life, Amy had a significant impact on the music Out of Rome - We leave the eternal city behind by way of the famous Apian Way to explore the industry and is a recognized name around the world. Her unique voice and fusion of styles left a environs of Rome. First it’s the majesty of Emperor Hadrian’s villa and lakes of the Alban Hills. musical legacy that will live long in the memory of everyone her music has touched. Next, it’s south to the ancient seaport of Ostia, Rome’s Pompeii. Along the way we sample olive oil, stop at the ancient’s favorite beach and visit a medieval hilltop town. Our own five star villa 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT is a retreat fit for an emperor. CMA Fest Thomas Rhett and Kelsea Ballerini host as more than 20 of your favorite artists perform their 6:30 AM ET / 3:30 AM PT newest hits, including Carrie Underwood, Blake Shelton, Keith Urban, Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan, Rock Legends Dierks Bentley, Thomas Rhett, Chris Stapleton, Kelsea Ballerini, Jake Owen, Darius Rucker, Broth- Pearl Jam - Rock Legends Pearl Jam tells the story of one of the world’s biggest bands, featuring ers Osborne, Lauren Alaina and more. insights from music critics and showcasing classic music videos. -

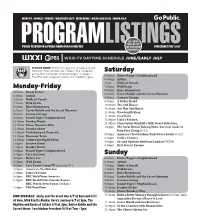

Program Listings

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW JUNE/EARLY JULY 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE JUNE/EARLY JULY PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete Saturday prime time television schedule begins on page 2. The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 6:30am Arthur 9:00am Curious George 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:30am A Wider World 7:30am Wild Kratts 10:00am This Old House 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:30am Ask This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:00am Curious George 11:30am Ciao Italia 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show/Survival Guide to 11:00am Sesame Street Pain Free Living (6/12) 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen/Rick Steves Awaits (6/12) 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! Sunday 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:00am Mister -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday May 21, 2018 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Steve Winwood Nashville A smooth delivery, high-spirited melodies, and a velvet voice are what Steve Winwood brings When You’re Tired Of Breaking Other Hearts - Rayna tries to set the record straight about her to this fiery performance. Winwood performs classic hits like “Why Can’t We Live Together”, failed marriage during an appearance on Katie Couric’s talk show; Maddie tells a lie that leads to “Back in the High Life” and “Dear Mr. Fantasy”, then he wows the audience as his voice smolders dangerous consequences; Deacon is drawn to a pretty veterinarian. through “Can’t Find My Way Home”. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT The Big Interview Foreigner Phil Collins - Legendary singer-songwriter Phil Collins sits down with Dan Rather to talk about Since the beginning, guitarist Mick Jones has led Foreigner through decades of hit after hit. his anticipated return to the music scene, his record breaking success and a possible future In this intimate concert, listen to fan favorites like “Double Vision”, “Hot Blooded” and “Head partnership with Adele. Games”. 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT Presents Phil Collins - Going Back Fleetwood Mac, Live In Boston, Part One Filmed in the intimate surroundings of New York’s famous Roseland Ballroom, this is a real Mick, John, Lindsey, and Stevie unite for a passionate evening playing their biggest hits. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. October 15, 2018 to Sun. October 21, 2018

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. October 15, 2018 to Sun. October 21, 2018 Monday October 15, 2018 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT John Mayer With Special Guest Buddy Guy The Big Interview John Mayer’s soulful lyrics, convincing vocals, and guitar virtuosity have gained him worldwide Dwight Yoakam - Country music trailblazer takes time from his latest tour to discuss his career fans and Grammy Awards. John serenades the audience with hits like “Neon”, “Daughters” and and how he made it big in the business far from Nashville. “Your Body is a Wonderland”. Buddy Guy joins him in this special performance for the classic “Feels Like Rain”. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT The Big Interview 9:00 PM ET / 6:00 PM PT Emmylou Harris - Spend an hour with Emmylou Harris, as Dan Rather did, and you’ll see why she The Life & Songs of Emmylou Harris: An All-Star Concert Celebration is a legend in music. Shot in January 2015, this concert features performances by Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, Conor Oberst, Daniel Lanois, Iron & Wine, Kris Kristofferson, Lucinda Williams, Martina McBride, 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT Mary Chapin Carpenter, Mavis Staples, Patty Griffin, Rodney Crowell, Sara Watkins, Shawn The Life & Songs of Emmylou Harris: An All-Star Concert Celebration Colvin, Sheryl Crow, Shovels & Rope, Steve Earle, The Milk Carton Kids, Trampled By Turtles, Vince Shot in January 2015, this concert features performances by Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, Gill, and Buddy Miller. Conor Oberst, Daniel Lanois, Iron & Wine, Kris Kristofferson, Lucinda Williams, Martina McBride, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Mavis Staples, Patty Griffin, Rodney Crowell, Sara Watkins, Shawn 11:00 PM ET / 8:00 PM PT Colvin, Sheryl Crow, Shovels & Rope, Steve Earle, The Milk Carton Kids, Trampled By Turtles, Vince Rock Legends Gill, and Buddy Miller. -

P36-40 Layout 1

lifestyle TUESDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2016 MUSIC & MOVIES Bob Dylan sends speech for Nobel ceremony usic icon Bob Dylan won't be at the Nobel prize cere- in a letter on November 16 that he would not attend the cere- "Absolutely. If it's at all possible." mony this week to accept his award, but he has sent mony because he had "pre-existing commitments", in an Academy member Swedish writer Per Wastberg accused Malong a speech to be read aloud, the Nobel founda- announcement that did not come as a surprise to observers. Dylan of being "impolite and arrogant", and said it was tion said yesterday. The 75-year-old, whose lyrics have influ- Several other prize winners have skipped the Nobel ceremony "unprecedented" that the academy did not know if Dylan enced generations of fans, has had a subdued response to the in the past for various reasons-Doris Lessing, who was too old; intended to pick up his award. But the first songwriter to win honor, remaining silent for weeks following the news in Harold Pinter, because he was hospitalized, and Elfriede the prestigious award in literature is expected to come to October he had won the prize for literature. "This year's Jelinek, who has social phobia. Stockholm early next year. Nobel laureates are honored every Laureate in Literature, Bob Dylan, will not be participating in Dylan did not say a word about his prize on the day it was year on December 10 -- the anniversary of the death of prize's the Nobel Week but he has provided a speech which will be announced, October 13, when he was performing in Las founder Alfred Nobel, a Swedish industrialist, inventor and read at the banquet," the foundation said in a statement. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2016 Remarks at the Kennedy Center

Administration of Barack Obama, 2016 Remarks at the Kennedy Center Honors Reception December 4, 2016 The President. Well, good evening, everybody. Audience members. Good evening! The President. On behalf of Michelle and myself, welcome to the White House. Over the past 8 years, this has always been one of our favorite nights. And this year, I was especially looking forward to seeing how Joe Walsh cleans up. [Laughter] Pretty good. [Laughter] I want to begin by once again thanking everybody who makes this wonderful evening possible, including David Rubenstein, the Kennedy Center Trustees—I'm getting a big echo back there—and the Kennedy Center President, Deborah Rutter. Give them a big round of applause. We have some outstanding Members of Congress here tonight. And we are honored also to have Vicki Kennedy and three of President Kennedy's grandchildren with us here: Rose, Tatiana, and Jack. [Applause] Hey! So the arts have always been part of life at the White House because the arts are always central to American life. And that's why, over the past 8 years, Michelle and I have invited some of the best writers and musicians, actors, dancers to share their gifts with the American people, and to help tell the story of who we are, and to inspire what's best in all of us. Along the way, we've enjoyed some unbelievable performances. This is one of the perks of the job that I will miss. [Laughter] Thanks to Michelle's efforts, we've brought the arts to more young people, from hosting workshops where they learn firsthand from accomplished artists, to bringing "Hamilton" to students who wouldn't normally get a ticket to Broadway. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

David Pack Facts at a Glance 2020

David Pack Facts at a Glance 2020 David Pack has won international acclaim both for his solo work and his stellar turn as co-founder & former frontman for the progressive rock group Ambrosia. He is a Grammy-winning Producer and Music Director/Producer of global special events including both of President Clinton’s Inaugurals, charitable events for Barbra Streisand, Elton John, Billy Joel, Madonna, Fergie, and an incredible host of others. His collected works as a performer and producer have sold over 50-million units worldwide. His music mentors are friends the late Leonard Bernstein and Quincy Jones. He is a two-time Grammy winner – for Tribute: Songs of Andrae Crouch and Handel’s Messiah – a Soulful Celebration. He has been nominated for seven additional Grammys – six for Ambrosia, one for Kenny Loggins’ Return to Pooh Corner. David’s all-star group “David Pack’s Legends Live” perform across America. Artists Produced Aretha Franklin, Faith Hill, Phil Collins, Garth Brooks, Kenny Loggins, Michael McDonald, Leann Rimes, Natalie Cole, Patti LaBelle, Trisha Yearwood, Selena, Amy Grant, Wynonna Judd, Brian Setzer, TLC, Brian McKnight, Little Richard, Patti Austin, Linda Ronstadt, James Ingram, Cece Winans, Pointer Sisters, Mavis Staples, Andrae Crouch, David Benoit, Take 6, Bruce Hornsby, Branford Marsalis, Chick Corea, Steve Vai, Tevin Campbell, Jerky Boys, Paul Rodriquez, Chet Atkins, Olivia Newton John, DC Talk, Jennifer Holliday Current Projects • Solo Album in progress 2019 – Touring with David Pack’s Legends Live • Barbra Streisand Walls Album (2018) David co-wrote lyrics “Take Care of This House” (Bernstein/Lerner) • The Bubble Musical - Soundtrack Album of David’s first Musical in progress • Ambrosia Ultimate Collection w/ Unreleased New Tracks in Progress 2019 • David Pack’s Napa Crossroads (Concord Records 2014) feat.