Ulnar Fracture with Late Radial Head Dislocation: Delayed Monteggia Fracture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CASE REPORT Injuries Following Segway Personal

UC Irvine Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health Title Injuries Following Segway Personal Transporter Accidents: Case Report and Review of the Literature Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/37r4387d Journal Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health, 16(5) ISSN 1936-900X Authors Ashurst, John Wagner, Benjamin Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.5811/westjem.2015.7.26549 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CASE REPORT Injuries Following Segway Personal Transporter Accidents: Case Report and Review of the Literature John Ashurst DO, MSc Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Benjamin Wagner, DO Johnstown, Pennsylvania Section Editor: Rick A. McPheeters, DO Submission history: Submitted April 20, 2015; Accepted July 9, 2015 Electronically published October 20, 2015 Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2015.7.26549 The Segway® self-balancing personal transporter has been used as a means of transport for sightseeing tourists, military, police and emergency medical personnel. Only recently have reports been published about serious injuries that have been sustained while operating this device. This case describes a 67-year-old male who sustained an oblique fracture of the shaft of the femur while using the Segway® for transportation around his community. We also present a review of the literature. [West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(5):693-695.] INTRODUCTION no parasthesia was noted. In 2001, Dean Kamen developed a self-balancing, zero Radiograph of the right femur demonstrated an oblique emissions personal transportation vehicle, known as the fracture of the proximal shaft of the femur with severe Segway® Personal Transporter (PT).1 The Segway’s® top displacement and angulation (Figure). -

Hand Rehabilitation Current Awareness Bulletin NOVEMBER 2015

1 Hand Rehabilitation Current Awareness Bulletin NOVEMBER 2015 2 Lunchtime Drop-in Sessions The Library and Information Service provides free specialist information skills training for all UHBristol staff and students. To book a place, email: [email protected] If you’re unable to attend we also provide one-to-one or small group sessions. Contact library@ or katie.barnard@ to arrange a session. Literature Searching October (12pm) An in -depth guide on how to search Thurs 8th Statistics the evidence base, including an introduction to UpToDate and Fri 16th Literature Searching Anatomy.tv. Mon 19th Understanding articles Tues 27th Statistics Useful for anybody who wants to find the best and quickest way to source articles. November (1pm) Weds 4th Literature Searching Thurs 12th Understanding articles How to understand an article Fri 20th Statistics How to assess the strengths and Mon 23rd Literature Searching weaknesses of published articles. Examining bias and validity. December (12pm) Tues 1st Understanding articles Weds 9th Statistics Medi cal Statistics Thurs 17th Literature Searching A basic introduction to the key statistics in medical articles. Giving an overview of statistics that compare risk, test confidence, analyse clinical investigations, and test difference. 3 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 3 New from Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews .......................................................................... -

Radial Head Fractures Treated with Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

Moghaddam et al. Trauma Cases Rev 2016, 2:028 Volume 2 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2469-5777 Trauma Cases and Reviews Research Article: Open Access Radial Head Fractures Treated with Open Reduction and Internal Fixation Moghaddam A1*, Raven TF1, Kaghazian P1, Studier-Fischer S2, Swing T1, Grützner PA2 and Biglari B2 1Trauma & Reconstructive Surgery, University hospital Heidelberg, Germany 2BG Unfallklinik, Ludwigshafen, Germany *Corresponding author: Prof. Dr. med. Arash Moghaddam, Consultant Orthopaedic & Trauma Surgeon Center of Trauma, Orthopaedics & Paraplegiology, Division of Trauma & Reconstructive Surgery, University hospital Heidelberg, Schlierbacher Landstraße 200a, 69118 Heidelberg, Germany, Tel: 0049-6221-5626263, Fax: 0049- 6221-26298, E-mail: [email protected] to a high percentage of associated injuries [6]. The combination of a Abstract dislocated fracture and unstable joint makes operative treatment as Background: Radial head fractures are responsible for 2 to 5% of well as early mobilization difficult. Other treatment options include adult fractures. Especially problematic is the treatment of dislocated the implantation of a radial head prosthesis and resection of the and unstable fractures which often have a worst prognosis. The radial head. The radial head prosthesis has become established as the purpose of this study was to evaluate the results of open reduction choice of treatment for multi-fragmented radial head fractures with and internal fixation (ORIF) in the treatment of radial head fractures. associated injuries, while resection of the radial head has increasingly Materials and Methods: Between June 2001 and January 2006, fallen out of use and is now reserved for isolated fractures of the 41 reconstructive surgical procedures were executed. Thirty-seven radial head without associated injuries [7]. -

Del Vecchio Upper Extremity Injury

UPPER EXTREMITY INJURIES Jeff Del Vecchio MPAS, PA-C, DFAAPA Mercy Clinic Orthopedics Springfield, Missouri OBJECTIVES IDENTIFY COMMON UPPER EXTREMITY INJURIES AND FRACTURES REVIEW EXAMINATION TECHNIQUES FOR COMMON UPPER EXTREMITY INJURIES DISCUSS AND REVIEW RADIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS OF UPPER EXTREMITY FRACTURES DISCUSS AND REVIEW TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR COMMON UPPER EXTREMITY INJURIES LATERAL EPICONDYLITIS Tennis elbow Definition Pain about lateral aspect of elbow Involves extensor musculature Rotation of arm and wrist extension Secondary to repetitive overuse or injury Microtears to tendon⇒ inflammation⇒fibrosis⇒degeneration Affects pt’s 30-60 yrs Clinical symptoms Outside elbow and back of upper forearm pain Pain lifting with palm facing down Holding lightweight objects difficult Physical Examination Lateral epicondylar area tender to palpation Tennis elbow test- elbow 90 deg, extend wrist against resistance. +pain at lateral epicondaylar area Radiographs Obtain to rule out osteoarthritis or calcifications Treatment NSAID’s (10-14 days) Avoid activities causing pain Heat or ice Corticosteroid injection Stretching and gradual strengthening program Tennis elbow strap MEDIAL EPICONDYLITIS Golfer’s elbow Definition Inflammation of flexor-pronator’s Less common than lateral epicondylitis Clinical Symptoms Medial elbow pain Physical Examination Pain with palpation over medial condyle Pain with flexion and pronation of wrist against resistance Rule out ulnar neuropathy Treatment Same as lateral epicondylitis CLAVICLE FRACTURE Most common bone injury -

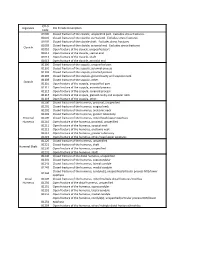

ICD*9, Diganosis ICD*9,Code,Description Code 81000 Closed,Fracture,Of,The,Clavicle,,Unspecified,Part.,,Excludes,Stress,Fractures

ICD*9, Diganosis ICD*9,Code,Description Code 81000 Closed,fracture,of,the,clavicle,,unspecified,part.,,Excludes,stress,fractures. 81001 Closed,fracture,of,the,clavicle,,sternal,end.,,Excludes,stress,fractures. 81002 Closed,fracture,of,the,clavicle,shaft.,,Excludes,stress,fractures. 81003 Closed,fracture,of,the,clavicle,,acromial,end.,,Excludes,stress,fractures. Clavicle 81010 Open,fracture,of,the,clavicle,,unspecified,part 81011 Open,fracture,of,the,clavicle,,sternal,end 81012 Open,fracture,of,the,clavicle,,shaft 81013 Open,fracture,of,the,clavicle,,acromial,end 81100 Closed,fracture,of,the,scapula,,unspecified,part 81101 Closed,fracture,of,the,scapula,,acromial,process 81102 Closed,fracture,of,the,scapula,,coracoid,process 81103 Closed,fracture,of,the,scapula,,glenoid,cavity,and,scapular,neck 81109 Closed,fracture,of,the,scapula,,other. Scapula 81110 Open,fracture,of,the,scapula,,unspecified,part 81111 Open,fracture,of,the,scapula,,acromial,process 81112 Open,fracture,of,the,scapula,,coracoid,process 81113 Open,fracture,of,the,scapula,,glenoid,cavity,and,scapular,neck 81119 Open,fracture,of,the,scapula,,other. 81200 Closed,fracture,of,the,humerus,,proximal,,unspecified 81201 Closed,fracture,of,the,humerus,,surgical,neck 81202 Closed,fracture,of,the,humerus,,anatomic,neck 81203 Closed,fracture,of,the,humerus,,greater,tuberosity Proximal, 81209 Closed,fracture,of,the,humerus,,other/head/upper,epiphysis Humerus 81210 Open,fracture,of,the,humerus,,proximal,,unspecified 81211 Open,fracture,of,the,humerus,,surgical,neck 81212 Open,fracture,of,the,humerus,,anatomic,neck -

Radial Head Fracture Repair and Rehabilitation

1 Radial Head Fracture Repair and Rehabilitation Surgical Indications and Considerations Anatomical Considerations: The elbow is a complex joint due to its intricate functional anatomy. The ulna, radius and humerus articulate in such a way as to form four distinctive joints. Surrounding the osseous structures are the ulnar collateral ligament complex, the lateral collateral ligament complex and the joint capsule. Four main muscle groups provide movement: the elbow flexors, the elbow extensors, the flexor-pronator group, and the extensor-supinator groups. Different types of radial head fractures can occur each of which has separate surgical indications and considerations. Fractures of the proximal one-third of the radius normally occur in the head region in adults and in neck region in children. The most recognized and used standard for assessing radial head fractures is the 4-part Mason classification system. It is used for both treatment and prognosis. Classification: Type I fracture A fissure or marginal fracture without displacement. Type II fracture Marginal fractures with displacement involving greater than 2 mm displacement. Type III fracture Comminuted fractures of the whole radial head. Type IV fracture (variation) A comminuted fracture, with an associated dislocation, ligament injury, coronoid fracture, or Monteggia lesion. Pathogenesis: Severe comminuted fractures or fracture dislocations of the head of the radius often occur as the result of a fall on an outstretched arm with the distal forearm angled laterally, or a valgus stress on the elbow. Fractures can also occur from a direct blow or force to the elbow (e.g. MVA). Chronic synovitis and mild deterioration of the articular surfaces associated with arthritis (e.g. -

Forearm Fractures Sean T

Forearm Fractures Sean T. Campbell, MD Assistant Attending Orthopedic Trauma Service Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY Core Curriculum V5 Objectives • Understand rationale for surgery for forearm fractures • Understand which segment is unstable based on injury pattern • Identify goals of surgery based on injury pattern • Review surgical techniques Core Curriculum V5 Introduction: Forearm Fractures • Young patients • Typically high energy injuries • Geriatric/osteopenic patients • May be low energy events • Mechanism • Fall on outstretched extremity • Direct blunt trauma Core Curriculum V5 Anatomy • Two bones that function as a forearm joint to allow rotation • Radius • Radial bow in coronal plane • Ulna • Proximal dorsal angulation in sagittal plane • Not a straight bone • Distinct bow in coronal plane (see next slides) • Proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ) • Articulation of radial head with proximal ulna • Distal radioulnar joint • Articulation of ulnar head with distal radius • Interosseous membrane Hreha J+, Snow B+ Image from: Jarvie, Geoff C. MD, MHSc, FRCSC*; Kilb, Brett MD, MSc, BS*,†; Willing, Ryan PhD, BEng‡; King, Graham J. MD, MSc, FRCSC‡; Daneshvar, Parham MD, BS* Apparent Proximal Ulna Dorsal Angulation Variation Due to Ulnar Rotation, Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma: April 2019 - Volume 33 - Issue 4 - p e120-e123 doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001408 Core Curriculum V5 Anatomy • Radial bow allows for pronosupination • Must be restored surgically when compromised • Multiple methods for assessment of radial bow • Comparison to contralateral images • Direct anatomic reduction of simple fractures • Biceps tuberosity 180 degrees of radial styloid • Note opposite apex medial bow of ulna • Not a straight bone Image from: Rockwood and Green, 9e, fig 41-9 Core Curriculum V5 Anatomy • Depiction of ulnar shape, noting proximal ulnar dorsal angulation (PUDA) in the top image, and varus angulation in the bottom image Image from: Jarvie, Geoff C. -

Radial Head Fracture

Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust Virtual Fracture Clinic Patient information Radial Head Fracture Radius Humerus Ulna Specialist Support This leaflet can be made available in another language, large print or another format. Please speak to the Virtual Fracture Clinic who can advise you Radial Head A5 leaflet 18 1035 bak.indd 1 19/03/2018 14:02:36 This information leaflet follows up your recent conversation with the Virtual Fracture Clinic, where your case was reviewed by an orthopaedic Consultant (Bone specialist). You have a break in the radial head (neck), which is one of the bones in your elbow. These fractures almost always heal well given time and movement. A sling has been provided for your comfort and should only be used for a few days. Movement is important to allow the fracture to heal and the elbow not to stiffen. The movement exercises below will help relieve some of the pain as well as helping you to recover well from your injury. Start these as soon as you are able. It is very important to keep moving the elbow gently and to gradually get back to normal daily activities within the limits of pain. There is however a risk that by forcibly stretching you may experience pain & delay your recovery. Painkillers are important to aid your recovery. Healing: This normally takes approximately 6 weeks to heal. Pain and swelling: Take regular over-the-counter analgesia (painkillers) until pain settles. To stop non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) e.g. Ibuprofen after 5-7 days as this will slow bone healing. -

Final Basic Fracture Overview for IPAS Fall CME 2014

11/5/14 I will try to make this painless Great, a Fracture, Now What? Mary Greve MS, PA-C Department of Orthopedic Surgery Trauma Team University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics [email protected] Pager 2121 Objectives Basics for Fracture Workup ¡ Lots of learners in clinic have the same ¡ History concerns and questions l Mechanism of injury? l How do I describe fractures competently? ¡ Tells you what to look for l What can I take care of? l Timing of injury? l What needs to be referred? ¡ New or old, has the patient been weight bearing etc. l Urgency ¡ We will cover some of the most common fractures that can be managed by PCPs Basics for Fracture Workup Basics of Fracture Workup ¡ Physical Exam ¡ X-rays l Always get at least 2 views of the injured area (at 90 deg l Inspection is much of exam angles to one another) ¡ Ecchymosis, swelling, skin exam, deformity, open fracture ¡ If you are unsure which films to get, call ortho or radiology l Neurovascular Checks ¡ X-rays of joint above and below injury if injury is to a long bone (ex: forearm fractures need elbow and l Exam of joints above and below wrist films) l Ok to ask for active range of motion but passive range of motion should not be done until x-rays are done 1 11/5/14 Distal Radius Fracture Basics of Fracture Workup ¡ Treatment l What can you do acutely? l Can the patient wait to see ortho? l Does the patient need to see ortho? ¡ Always important to get two views at 90 deg angles to one another Giving an Expert Presentation Other things to communicate ¡ When calling ortho, be able -

Traumatic Injuries: Imaging of Peripheral Muskuloskeletal Injuries 2.11

Chapter Traumatic Injuries: Imaging of Peripheral Muskuloskeletal Injuries 2.11 M.A. Müller, S. Wildermuth, K. Bohndorf Contents In past years, computed tomography (CT) has gained an important place in the emergency evaluation of fractures 2.11.1 Introduction . 251 and in planning surgery of complex injuries. Magnetic res- 2.11.2 General Part: Imaging Modalities . 251 onance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound (US) are important 2.11.2.1 Conventional Radiography imaging modalities in the evaluation of soft tissues in addi- (Projection Radiography) . 251 tion to the clinical examination. 2.11.2.2 Computed Tomography . 252 2.11.2.3 Magnetic Resonance Imaging . 252 2.11.2.4 Ultrasound . 253 2.11.3 Soft Tissue Injuries in General . 253 2.11.2 General Part: Imaging Modalities 2.11.3.1 Muscle Injuries . 253 2.11.3.2 Tendinous and Ligamentous Injuries on US . 254 2.11.2.1 Conventional radiography (Projection radiography) 2.11.4 Upper Extremity . 254 2.11.4.1 The Clavicle and its Articulations . 254 2.11.4.2. Shoulder and Proximal Humerus . 256 Two projections perpendicular to each other preceded by 2.11.4.3 Elbow . 260 clinical examination are generally the first and often the 2.11.4.4 Distal Forearm and Wrist . 265 only necessary diagnostic approach in evaluation of ex- 2.11.4.5 Metacarpals and Fingers . 271 tremity trauma. Clinical prediction rules and cost-effec- 2.11.5 Lower Extremity . 273 tiveness analyses are valuable evidence-based tools for 2.11.5.1 Hip . 273 selecting optimal imaging approaches [1]. Conventional 2.11.5.2 Knee . -

Operative Fixation of Radial Head Fractures John T

Techniques in Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 8(2):89–97, 2007 Ó 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia | TECHNIQUE | Operative Fixation of Radial Head Fractures John T. Capo, MD and Dan Dziadosz, MD Division of Hand and Microvascular Surgery Department of Orthopaedics New Jersey Medical School Newark, NJ | ABSTRACT placement with rigid implant arthroplasty. Beingessner et al9 investigated the biomechanical effects of radial The radial head is an important structure that is crucial head excision and prosthetic arthroplasty on elbow to the stability of both the elbow and forearm. Fractures of the radial head occur commonly and often are dis- kinematics in a cadaver model. They demonstrated that replacement of the radial head with a metallic implant placed or cause impingement to forearm rotation. improves stability but does not return the elbow to a Recent studies have further demonstrated the impor- normal condition. This effect was most clearly seen tance of maintaining or reconstructing the rigid buttress with associated ligamentous instability and emphasized of the radial head. Advances in implant technology have that rigid implants do not exactly reproduce the benefited orthopedic surgeons in their attempts at dynamics of the intact or rigidly fixed radial head. The fixation of the radial head and also in rigid implant native radial head is also elliptical and sits at approxi- arthroplasty. Partial articular fractures of the radial head are relatively simple to repair and can be stabilized with mately a 15-degree angle to the radial shaft. These anatomic characteristics are not replicated by implant headless or buried screws. A complete articular fracture arthroplasty. -

Current Recommendations for the Treatment of Radial Head Fractures Yishai Rosenblatt, MD, George S

Orthop Clin N Am 39 (2008) 173–185 Current Recommendations for the Treatment of Radial Head Fractures Yishai Rosenblatt, MD, George S. Athwal, MD, FRCSC, Kenneth J. Faber, MD, MHPE, FRCSC* Hand and Upper Limb Centre, St. Joseph’s Health Care, University of Western Ontario, 268 Grosvenor Street, London, Ontario, Canada N6A 4L6 Radial head fractures are the most common which is the primary stabilizer against valgus type of elbow fractures. These fractures can occur force [23–26]. The radial head is also an important in isolation or be associated with other elbow axial stabilizer of the forearm and resists varus fractures and ligament injuries. Associated in- and posterolateral rotatory instability by tension- juries include coronoid fractures, distal humerus ing the lateral collateral ligament [27,28]. In addi- articular shear fractures, Monteggia’s fractures, tion, up to 60% of the load transfer across the and disruption of the collateral ligaments, inter- elbow occurs through the radiocapitellar articula- osseous ligaments, or both [1–3]. tion [29]. Although a consensus has emerged that favors Radial head fractures typically result from the nonsurgical treatment of undisplaced fractures a fall on the outstretched arm. Axial, valgus, [4], controversy surrounds the treatment of dis- and posterolateral rotational patterns of loading placed radial head fractures [5]. Options for the are all thought to be potentially responsible for treatment of displaced fractures include nonoper- these fractures (Fig. 1A–C). An axial force applied ative management, fragment excision [6,7], whole to the wrist is transmitted proximally and can exit head excision [8–10], open reduction and internal through the radial head.