Download This Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. G1--' 419 -.7- \99Ditj1'

NOTICE OF MEETING FOR CORPORATION OF THE MUNICIPALITY OF BRIGHTON BOX 189, BRIGHTON, ONT. KOK IHO MEETING DATE: January 8, 2007 TIME: 7:00 P.M. - AGENDA - 1. CALL TO ORDER- APPROVAL OF AGENDA- 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES — Approval of December 18/06 Minutes 3. DECLARATIONS OF PECUNIARY INTERESTS 4. ( PLANNING ISSUES 1) By-Law Number 426-2007 — Rezoning George & Diane Allore- Proposed Kennel 5. DELEGATIONS “I) Rick Norlock, MP _2) Nancy Anderson — Setting Up a Municipal Heritage Committee 3) Dave Cutler — Setting Up a Local Architectural Advisory Committee _4) Rev. Doug Brown & Rev. Rylan Montgomery- St. Andrews Presbyterian Church 5) Correspondence The Presbytery of Lindsay-Peterborough re: Andrew’s Presbyterian Church 6) Correspondence from Joan Waddling re: St. Andrews Presbyterian Church 7) Correspondence from Margaret & Joe Sare re: St. Aiidrews Presbyterian Church 6. STAFF UPDATES I) CAO, Bruce Davis 7. UNFINISHED BUSINESS - 8. NEW BUSINESS - 9. RESOLUTIONS & BY-LAWS - 1. Approval of Accounts 2. By-Law Number — 428-2007 Interim Tax Levy . I 3. G1--’ 419 -.7- \99DitJ1’ 10. REPORTS OF COMMITTEES AND BOARIS - NONE 11. CORRESPONDENCE - 1) LTC —2007 Business Plan/Levy 2) Quinte Access — Update 3) Northumberland Food for Thought — Request Support 4) BHSC — Loan Update 5) Year End Summary — MPP Lou Rinaldi 6) MMAH — Amendments to Municipal Act, 2001 Proclaimed 7) McGuinty Gov’t Improves Local Planning 8) City of Toronto Act 2006 Proclaimed 9) IVTIVIAH — Energy-Efficient Building Standards in Canada 10) AJvIO Alert — OMPF Allocations for 2007 / ‘-p 11) Press Release MPP Rinaldi — OMPF 12) MMAH — Municipal Statule Law Amendment Act 2006 13) Ontario Parks — Deer Herd Reduction to Move Fonvard 14) Letter to Peaceflul Parks Coalition 15) Letter to MNR re: Cormorant Management 12. -

Lower Trent Source Protection Area

VU37 Tweed North Bay Marmora VU37 Georgian Bay VU28 Township of Havelock-Belmont-Methuen HASTINGS COUNTY Lake Huron Kingston Havelock Lower Trent Toronto Lake OntarioWarsaw Lakefield Source Protection Area Ivanhoe Watershed Boundaries Lake Erie Norwood Legend VU62 Township of Stirling-Rawdon Roslin " Settlements 938 938 Township of Centre Hastings Railway PETERBOROUGH COUNTY Highway Multi-lane Highway Campbellford Watercourse Hastings Stirling Lower Tier Municipality 935 Upper and Single Tier Municipality Waterbody 98 Source Protection Area 45 9 Foxboro Municipality of Trent Hills 930 Keene CITY OF QUINTE WEST 924 Frankford Rice Lake Warkworth Roseneath Belleville 929 VU401 Wooler 940 Harwood NORTHUMBERLAND COUNTY Gores Landing Trenton 925 Municipality of Brighton Castleton ± Centreton 922 0 3 6 12 18 Bay of Quinte 92 Kilometres 23 9 Brighton Township of Cramahe Little Trent Conservation Coalition Lake Source Protection Region Camborne www.trentsourceprotection.on.ca Township of Alnwick/Hadimand Baltimore THIS MAP has been prepared for the purpose of meeting the 2 Colborne9 Consecon provincial requirements under the Clean Water Act, 2006. If it is proposed to use it for another purpose, it would be advisable to first consult with the responsible Conservation Authority. Grafton PRODUCED BY Lower Trent Conservation on behalf of the Trent Conservation Coalition Source Protection Committee, March 2010, with data supplied under licence by members of the Ontario Geospatial Data Exchange. Wellington Lake Ontario Made possible through the support -

OWER Trentconse:RVAT IO Ea“ F 714 Murraystreet, R.R

LOWERTRENT3 I R_. 2 U. LOWER TRENTCoNsE:RVAT IO Ea“ f 714 MurrayStreet, R.R. 1, Trenton, Ontario K8V5P-1 N 14 Tel: (613)394-4829 Fax: (613)394-5226 Website: vwvw.|l.<':.0n.ca Email: information@| O Registered Charimhle(1):g,anizaliunNu. 1(17G4b?FJ8R0001 2 l.<:.on.ca Low Water Response Team Meeting MINUTES- Draft Date: August 4, 2016 at 2:00 PM Location: Lower Trent Conservation Administrative Office,714 Murray Street, Trenton ATTENDEES: Lower Trent Conservation — Glenda Rodgers, Janet Noyes, Marilyn Bucholtz, RileyAllen Alnwick/Haldimand— Raymond Benns, John Logel Brighton — Mark Walas, Mary Tadman, John Martinello, Mark Ryckman Centre Hastings — EricSandford, Roger Taylor Cramahe —Jeannie Mintz Quinte West —Jim Harrison, Jim Alyea, Karen Sharpe, Chris Angelo Stirling-Rawdon — Bob Mullin, Matthew Richmond Trent Hills— RickEnglish, Scott White Northumberland County — Ken Stubbings Hastings County — Leanne Latter, Justin Harrow, Jim Duffin Ministry of Natural Resources & Forestry (MNRF)—JeffWiltshire Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food & RuralAffairs (OMAFRA)— Peter Doris Ministry of the Environment & Climate Change (MOECC)— Peter Taylor Northumberland Federation of Agriculture - AllanCarruthers Metroland Media — Erin Stewart 1. Welcome 8: Introductions Glenda Rodgers welcomed everyone and introductions were made 2. Introduction Janet Noyes provided an overview of the Ontario Low Water Response Program which includes 3 status levels based on precipitation and stream flow conditions. 3. Water Response To date, the current Lower Trent Conservation -

Trent River Truckin'

Trent River Truckin’ Warkworth’s artisan shops • Campbellford’s flavours DISCOVER: 01 Cafés & Artisan Shops from chocolate to beer • The Trent-Severn Waterway Main St., Warkworth Park your bike and visit Warkworth’s shops 63 and galleries. Bakeries with butter tarts are KILOMETERS Trent River a must visit. 1 – 6% AVERAGE SLOPE 02 Ranney Gorge Suspension Bridge Healey 04 Campbellford • 888-653-1556 VisitTrentHills.ca Falls 12th Line E Cycle across the Suspension Bridge and feel Crowe Bridge Park the thrill of being suspended above the gorge. Crowe River A Trans Canada Trail highlight. 50 30 Hastings 03 Church-Key Brewing 1678 County Rd. 38, Campbellford 05 P 38 877-314-2337 • ChurchKeyBrewing.com 8th Line E Taste award-winning, handcrafted ales 06 at the micro-brewery in this former 1878 P 03 Methodist church. 35 45 Bannon Campbellford 04 Crowe Bridge Park 670 Crowe River Rd., Campbellford 6th Line W Ferris Hike the trails along the pristine Crowe River. 5th Line W Dip your toes in the falls. Godolphin 26 Skinkle Mahoney 05 Giant Toonie & Campbellford 30 02 55 Grand Rd., Campbellford Seymour 8 25 Conc. Rd. 6 E. Picnic at the giant Toonie coin monument. Roseneath Meyersburg Tour the town to try sweets from butter tarts Peterborough to the World’s Finest chocolate. 18 Godolphin Westben Arts Festival Theatre Ganaraska Rice Lake Alderville 06 Forest Harwood Warkworth 6698 County Rd. 30 N., Campbellford Gores 877-883-5777 • westben.ca 28 29 Landing P Treat yourself to a performance in this 01 Warkworth 400-seat barn, or just cycle by. -

Trent-Severn & Lake Simcoe

MORE THAN 200 NEW LABELED AERIAL PHOTOS TRENT-SEVERN & LAKE SIMCOE Your Complete Guide to the Trent-Severn Waterway and Lake Simcoe with Full Details on Marinas and Facilities, Cities and Towns, and Things to Do! LAKE KATCHEWANOOKA LOCK 23 DETAILED MAPS OF EVERY Otonabee LOCK 22 LAKE ON THE SYSTEM dam Nassau Mills Insightful Locking and Trent University Trent Boating Tips You Need to Know University EXPANDED DINING AND OTONABEE RIVER ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE dam $37.95 ISBN 0-9780625-0-7 INCLUDES: GPS COORDINATES AND OUR FULL DISTANCE CHART 000 COVER TS2013.indd 1 13-04-10 4:18 PM ESCAPE FROM THE ORDINARY Revel and relax in the luxury of the Starport experience. Across the glistening waters of Lake Simcoe, the Trent-Severn Waterway and Georgian Bay, Starport boasts three exquisite properties, Starport Simcoe, Starport Severn Upper and Starport Severn Lower. Combining elegance and comfort with premium services and amenities, Starport creates memorable experiences that last a lifetime for our members and guests alike. SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE… As you dock your boat at Starport, step into a haven of pure tranquility. Put your mind at ease, every convenience is now right at your fi ngertips. For premium members, let your evening unwind with Starport’s turndown service. For all parents, enjoy a quiet reprieve at Starport’s on-site restaurants while your children are welcomed and entertained in the Young Captain’s Club. Starport also offers a multitude of invigorating on-shore and on-water events that you can enjoy together as a family. There truly is something for everyone. -

Impact of the Monthly Variability of the Trent River on the Hydrodynamical Conditions of the Bay of Quinte, Ontario: a Case Study 2016–2019

water Article Impact of the Monthly Variability of the Trent River on the Hydrodynamical Conditions of the Bay of Quinte, Ontario: A Case Study 2016–2019 Jennifer A. Shore Physics and Space Science, Royal Military College of Canada, Kingston, ON K7K 7B4, Canada; [email protected] Received: 3 August 2020; Accepted: 24 September 2020; Published: 25 September 2020 Abstract: The spatial and temporal (monthly) variability of river discharge has a significant effect on circulation and transport pathways within shallow embayments whose dynamics are largely controlled by wind and riverine inputs. This study illustrates the effects of the monthly variation in Trent River discharge on simulated particle transport and settling destination in the Bay of Quinte, Lake Ontario for the years 2016–2019. Observations of Lagrangian surface drifter data were used to derive Trent River discharge forcing for a three-dimensional hydrodynamic numerical model of the Bay of Quinte. Peak monthly flushing was up to three times as much as the lowest monthly flushing in any year, with the Trent River responsible for up to 95% of the flushing in low runoff years. Particle transport simulations showed that particles could be trapped along shorelines, which extended residence times, and Trent River releases suggest that researchers should look for delayed peaks in Total Phosphorous (TP) load measurements in observations between Trenton and Belleville as particles move downstream. Particles with constant settling velocities originating from the Trent River did not move downstream past Big Bay, and particles from the Napanee River were the primary source for Longreach. Keywords: river discharge variability; flushing; particle transport and fate; Bay of Quinte; Finite Volume Community Ocean Model (FVCOM) 1. -

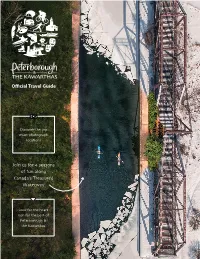

Official Travel Guide

Official Travel Guide Discover the top must-photograph locations Join us for 4 seasons of fun along Canada’s Treasured Waterway Look for the heart icon for the best-of Peterborough & the Kawarthas DISCOVER NATURE 1 An Ode to Peterborough & the Kawarthas Do you remember that We come here to recharge and refocus – to share a meal made of simple, moment? Where time farm-fresh ingredients with friends stood still? Where life (old & new) – to get away until we’ve just seemed so clear. found ourselves again. So natural. So simple? We grow here. Remaining as drawn to this place as ever, as it evolves and Life is made up of these seemingly changes, yet remains as brilliant in our small moments and the places where recollections as it does in our current memories are made. realities. We love this extraordinary place that roots us in simple moments We were children here. We splashed and real connections that will bring carefree dockside by day, with sunshine us back to this place throughout the and ice cream all over our faces. By “ It’s interesting to view the seasons seasons of our life. night, we stared up from the warmth as they impact and change the of a campfire at a wide starry sky We continue to be in awe here. region throughout the year. fascinated by its bright and To expect the unexpected. To push The difference between summer wondrous beauty. the limits on seemingly limitless and winter affects not only the opportunities. A place with rugged landscape, but also how we interact We were young and idealistic here. -

Shadow Lake and Silver Lake Watershed Characterization Report

Silver and Shadow Lakes Watershed Characterization Report 2018 About Kawartha Conservation Who we are We are a watershed-based organization that uses planning, stewardship, science, and conservation lands management to protect and sustain outstanding water quality and quantity supported by healthy landscapes. Why is watershed management important? Abundant, clean water is the lifeblood of the Kawarthas. It is essential for our quality of life, health, and continued prosperity. It supplies our drinking water, maintains property values, sustains an agricultural industry, and contributes to a tourism-based economy that relies on recreational boating, fishing, and swimming. Our programs and services promote an integrated watershed approach that balance human, environmental, and economic needs. The community we support We focus our programs and services within the natural boundaries of the Kawartha watershed, which extend from Lake Scugog in the southwest and Pigeon Lake in the east, to Balsam Lake in the northwest and Crystal Lake in the northeast – a total of 2,563 square kilometers. Our history and governance In 1979, we were established by our municipal partners under the Ontario Conservation Authorities Act. The natural boundaries of our watershed overlap the six municipalities that govern Kawartha Conservation through representation on our Board of Directors. Our municipal partners include the City of Kawartha Lakes, Region of Durham, Township of Scugog, Township of Brock, Municipality of Clarington, Municipality of Trent Lakes, and Township of Cavan Monaghan. Kawartha Conservation 277 Kenrei Road, Lindsay ON K9V 4R1 T: 705.328.2271 F: 705.328.2286 [email protected] KawarthaConservation.com ii SHADOW LAKE WATERSHED CHARACTERIZATION REPORT – 2018 KAWARTHA CONSERVATION Acknowledgements This Watershed Characterization Report was prepared by the Technical Services Department team of Kawartha Conservation with considerable support from other internal staff and external organizations. -

Cultural Heritage Assessment Report

HERITAGE ASSESSMENT REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE ASSESSMENT REPORT MUNICIPAL CLASS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROPOSED REPLACEMENT OF THE WESTWOOD BRIDGE HAMLET OF WESTWOOD LOTS 10 & 11, CONCESSION II GEOGRAPHIC TOWNSHIP OF ASPHODEL TOWNSHIP OF ASPHODEL-NORWOOD COUNTY OF PETERBOROUGH, ONTARIO Submitted to: Tyler Clements HP Engineering Ottawa Submitted by: Heather Rielly MCIP RPP CAHP Ainley Group Belleville March, 2019 RequestMARCH for 2019 Proposal AINLEY FILE # 18571-1 45 South Front Street, Belleville, ON, K8N 2Y5 TEL: (613) 966-4243 EMAIL: [email protected] WWW.AINLEYGROUP.COM COUNTY OF PETERBOROUGH CULTURAL HERITAGE ASSESSMENT REPORT, March 2019 For the WESTWOOD BRIDGE, Site No. 099021 - Hamlet of WESTWOOD Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Study Purpose and Method .................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Data Collection ........................................................................................................................................ 5 2. THE STUDY AREA ................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Location and Physical Context ................................................................................................................ 5 2.2 Historical Context ................................................................................................................................... -

Archaeological

1.0 PROJECT REPORT COVER PAGE LICENSEE INFORMATION: Contact Information: Michael B. Henry CD BA FRAI FRSA Southwestern District Office 553 Dufferin Avenue London, ON N6B 2A5 Phone: (419) 432-4435 Email: [email protected]/[email protected] www.amick.ca Licensee: Sarah MacKinnon MSc Ontario Archaeology Licence: P1024 PROJECT INFORMATION: Corporate Project Number: 16011 MTCS Project Number: P1024-0201-2016 Investigation Type: Stage 1-2 Archaeological Assessment Project Name: Trenton Lock 1 Hydro Project Project Location: Part of Lots 2 & 3, Concession 2 (Geographic Township of Murray, County of Northumberland), City of Quinte West (Trenton Ward) Project Designation Number: N/A MTCS FILING INFORMATION: Site Record/Update Forms: N/A Date of Report Filing: 10 April 2017 Type of Report: ORIGINAL 2016 Stage 1-2 Archaeological Assessment of the Proposed Trenton Lock 1 Hydro Project, Part Lots 2 & 3, Con. 2 (Geographic Township of Murray, County of Northumberland), City of Quite West (Trenton Ward) (AMICK File #16011/MTCS File #P1024-0201-2016) 2.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report describes the conduct and results of the 2016 Stage 1-2 Archaeological Property Assessment of the Proposed Trenton Lock 1 Hydro Project, Part Lots 2 & 3, Con. 2 (Geographic Township of Murray, County of Northumberland), City of Quinte West (Trenton Ward), conducted by AMICK Consultants Limited. This study was conducted under Professional Archaeologist License #P1024 issued to Kayleigh MacKinnon by the Minister of Tourism, Culture and Sport for the Province of Ontario. This assessment was undertaken in order to ensure that the requirements of the Provincial Policy Statement are addressed since changes in land use are contemplated. -

Characteristics of the Exchange Flow of the Bay of Quinte and Its Sheltered Embayments with Lake Ontario

water Article Characteristics of the Exchange Flow of the Bay of Quinte and Its Sheltered Embayments with Lake Ontario Jennifer A. Shore Physics and Space Science, Royal Military College of Canada, Kingston, ON K7K 7B4, Canada; [email protected] Abstract: The nature of the exchange flow between the Bay of Quinte and Lake Ontario has been studied to illustrate the effects of the seasonal onset of stratification on the flushing and transport of material within the bay. Flushing is an important physical process in bays used as drinking water sources because it affects phosphorous loads and water quality. A 2-d analytical model and a 3-dimensional numerical coastal model (FVCOM) were used together with in situ observations of temperature and water speed to illustrate the two-layer nature of the late summer exchange flow between the Bay of Quinte and Lake Ontario. Observations and model simulations were performed for spring and summer of 2018 and showed a cool wedge of bottom water in late summer extending from Lake Ontario and moving into Hay Bay at approximately 3 cm/s. Observed and modelled water speeds were used to calculate monthly averaged fluxes out of the Bay of Quinte. After the thermocline developed, Lake Ontario water backflowed into the Bay of Quinte at a rate approximately equal to the surface outflow decreasing the flushing rate. Over approximately 18.5 days of July 2018, the winds were insufficiently strong to break down the stratification, indicating that deeper waters of the bay are not well mixed. Particle tracking was used to illustrate how Hay Bay provides a habitat for algae growth within the bay. -

The Heritage Gazette of the Trent Valley

ISSN 1206-4394 The herITage gazeTTe of The TreNT Valley Volume 20, Number 1, may 2015 President’s Corner …………………………………………………..………………………………. Guy Thompson 2 Champlain’s Route to Lake Ontario? …………………………………………………………… Stewart Richardson 3 Champlain and the 5th Franco-Ontarian Day …………………………………..…… Peter Adams and Alan Brunger 10 Trent University and Samuel de Champlain …………………………………………. Alan Brunger and Peter Adams 11 Fellows in the News [Alan Brunger and Peter Adams] ……………………………………………………………….. 13 Celebrate the Tercentenary at Kawartha Lakes …………………………..… Peterborough Examiner, 7 August 1914 13 Morris Bishop’s Account of Champlain in Ontario, from his book Champlain: the Life of Fortitude, 1948 ……………………..……. Peter Adams and Alan Brunger 14 A Concise History of the Anishnabek of Curve Lake ……………………………………………………. Peter Adams 17 The Architectural Legacy of the Bradburns …………………………………………………………… Sharon Skinner 19 The Bradburn Family ………………………………………………………..…………………………. Sharon Skinner 23 Queries ………………………………...………………………………… Heather Aiton Landry and Elwood H. Jones 25 Chemong Floating Bridge 25; Meharry 25; Cavan Death of an Old Resident 26; An Electric Car Built in Peterborough: No! 26; Peter Lemoire 32 Peter Robinson Festival: Summer heritage and performing arts festival takes place on Civic Holiday long weekend … 27 Marble slab advertising mystery is partly solved ……………………….. Elwood H. Jones, Peterborough Examiner 27 News, Views and Reviews ……………………………………………………………….………… Elwood H. Jones 29 Peterborough Museum and Archives 29; CHEX-TV at 60 29; County people tour TVA 29; Douro’s Tilted Crumpling Cross 29; Irish Heritage Event was Great Success 30; Pioneer Days in Hastings & District 31 (The French Village, Lemoire family) 32; Italian Club Dinner 33; Daniel Macdonald monument at Little Lake Cemetery 33; OGS Toronto Conference 33; Love in the Air: Second World War Letters (CHEX-TV report by Steve Guthrie) Joanne Culley 33; Lazarus Payne: Growing Up in Dummer 34; Book notes 35 Archaeology of Lake Katchewanooka ………………………………………………….…………….