17. New House, New Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Removal of Whitlam

MAKING A DEMOCRACY to run things, any member could turn up to its meetings to listen and speak. Of course all members cannot participate equally in an org- anisation, and organisations do need leaders. The hopes of these reformers could not be realised. But from these times survives the idea that any governing body should consult with the people affected by its decisions. Local councils and governments do this regularly—and not just because they think it right. If they don’t consult, they may find a demonstration with banners and TV cameras outside their doors. The opponents of democracy used to say that interests had to be represented in government, not mere numbers of people. Democrats opposed this view, but modern democracies have to some extent returned to it. When making decisions, governments consult all those who have an interest in the matter—the stake- holders, as they are called. The danger in this approach is that the general interest of the citizens might be ignored. The removal of Whitlam The Labor Party captured the mood of the 1960s in its election campaign of 1972, with its slogan ‘It’s Time’. The Liberals had been in power for 23 years, and Gough Whitlam said it was time for a change, time for a fresh beginning, time to do things differently. Whitlam’s government was in tune with the times because it was committed to protecting human rights, to setting up an ombuds- man and to running an open government where there would be freedom of information. But in one thing Whitlam was old- fashioned: he believed in the original Labor idea of democracy. -

Whitlam As Internationalist: a Centenary Reflection

WHITLAM AS INTERNATIONALIST: A CENTENARY REFLECTION T HE HON MICHAEL KIRBY AC CMG* Edward Gough Whitlam, the 21st Prime Minister of Australia, was born in July 1916. This year is the centenary of his birth. It follows closely on his death in October 2014 when his achievements, including in the law, were widely debated. In this article, the author reviews Whitlam’s particular interest in international law and relations. It outlines the many treaties that were ratified by the Whitlam government, following a long period of comparative disengagement by Australia from international treaty law. The range, variety and significance of the treaties are noted as is Whitlam’s attraction to treaties as a potential source of constitutional power for the enactment of federal laws by the Australian Parliament. This article also reviews Whitlam’s role in the conduct of international relations with Australia’s neighbours, notably the People’s Republic of China, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and Indochina. The reconfiguration of geopolitical arrangements is noted as is the close engagement with the United Nations, its agencies and multilateralism. Whilst mistakes by Whitlam and his government are acknowledged, his strong emphasis on international law, and treaty law in particular, was timely. It became a signature theme of his government and life. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 852 II Australia’s Ratification of International Treaties ................................................. -

Kirribilli House Bathing Pool and Early Harbourside Pools in Sydney

THE AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY FOR HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY INCORPORATED RESEARCH BULLETIN Registered for posting as a Box J20 HoI•• BuildlnC publication Catagory B NBG8545. Unl.eratt7 or B7dne7 2006 ISSN 0819-4076. Telephone (02) 6i2 2163 Winter, 1987 Number 2 KIRRIBILLI HOUSE BATHING POOL AND EARLY HARBOURS IDE POOLS IN SYDNEY :A BRIEF SURVEY Grace Karskens Introduction I was commissioned in 1986 to assess the cultural signifi cance of the stone harbourside pool at Kirribilli House, Kirribilli, N.S.W .• The pool was presumably built by merchant Adolph Feez, of Rabonne Feez and Co., who purchased a portion of the adjoining Wotonga (now Admiralty House) in 1854, and built the twin gabled house on it in ~he following year. To make this assessment it was necessary first to ascertain the popularity of recreational bathing' during the 1850s, and hence the likely number of private bathing pools built; and second to determine the present-day survival of such pools. Historical Outline A brief overview of the history of nineteenth-century bathing indicates four stages in the growth of this past-timers popularity: Stage 1: During the early period (1788-c1820) bathing for recreation occurred informally - convicts and ordinary settlers bathed in the sea and the rivers. Stage 2: From c1825-1850 bathing for ordinary people was formalised by the establishment of pUblic baths in the Domain in Woolloomooloo Bay by order of Governor Darling in 1829. 2. Bathers also swam in Darling Harbour. By 1853 the Surveyor General's map of Sydney Harbour shows four public baths in Woolloomooloo Bay, as well as the Governor's Bath House (see M.L. -

From Track to Tarmac

Federation Faces and Introduction A guided walk around the streets and laneways Places of North Sydney focusing on our Federation connections, including the former residences of A walking tour of Federation Sir Joseph Palmer Abbott, Sir Edmund Barton faces and places in North and Dugald Thomson. Along the walk, view the Sydney changes in the North Sydney landscape since th Federation and the turn of the 20 century. Distance: 6 Km Approximate time: 4 hours At the turn of the year 1900 to 1901 the city of Grading: medium to high Sydney went mad with joy. For a few days hope ran so high that poets and prophets declared Australia to be on the threshold of a golden age… from early morning on the first of January 1901 trams, trains and ferry boats carried thousands of people into the city for the greatest day of their history: the inauguration of the Commonwealth of Australia. It was to be a people‟s festival. Manning Clark, Historian It was also a people‟s movement and 1901 was the culmination of many years of discussions, community activism, heated public debates, vibrant speeches and consolidated actions. In 1890 the Australasian Federal Conference was held in Melbourne and the following year in Sydney. In 1893 a meeting of the various federation groups, including the Australian Native Association was held at Corowa. A plan was developed for the election of delegates to a convention. In the mid to late 1890s it was very much a peoples‟ movement gathering groundswell support. In 1896 a People‟s Convention with 220 delegates and invited guests from all of the colonies took place at Bathurst - an important link in the Federation chain. -

2012 Canberra Tour

2012 Canberra Tour 149 students are going on camp. The Teachers attending the Camp are: Jamie Peters, Melissa Bull, Natasha Richardson, Simon Radford, Melissa Brown, Crissy Samaras, Sarah Nobbs and Felicity Minton. Vicki Symons and Malinda Vaughn(Fri) will be at school to run the „At School Program‟. Off to Canberra –Get to school on time The departure date for the camp is Monday 30th of April (Week 3 of Term 2). Students are expected to be at school no later than 7:15am as the bus is leaving at 7.30. Make sure you get signed off when you arrive –there will be signs for you to know where you have to line up. If your child has any medication they must be at school between 7:00-7:15am to hand in their medication to Sarah Nobbs in the Gym foyer. We catch the bus back to school on Friday 4th May returning at approximately 5:30pm. WHY GO TO CANBERRA ? It is part of the school‟s camp policy, that this Educational Tour of Canberra is ran every second year to empower our students to become better citizens with valuable knowledge in Civics and Citizenship, Australian History and the Australian Government. What happens during the day on Camp? Each day the students will be touring the sights of Canberra. The tour destinations shown later in this presentation will be conducted by professional guides. The tours are aimed at the interest of grade 5/6 students and are interactive where appropriate. Some of the Evening Activities may include: – A Movie night – A Night Tour – Mount Ainslie – Common Room Free Activities – A Disco/Quiet games - A Trivia Night Day 1 Itinerary Monday, 30th April 2012 7.00am - Coaches arrive at Williamstown North Primary School to load luggage. -

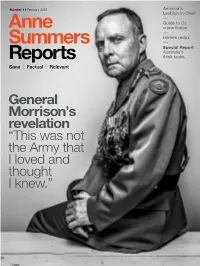

2015 Anne Summers Issue 11 2015

Number 11 February 2015 America’s Lesbian-in-Chief Guide to Oz crime fiction Harlem redux Special Report Australia’s think tanks Sane Factual Relevant General Morrison’s revelation “This was not the Army that I loved and thought I knew.” #11 February 2015 I HOPE YOU ENJOY our first issue for 2015, and our eleventh since we started our digital voyage just over two years ago. We introduce Explore, a new section dealing with ideas, science, social issues and movements, and travel, a topic many of you said, via our readers’ survey late last year, you wanted us to cover. (Read the full results of the survey on page 85.) I am so pleased to be able to welcome to our pages the exceptional mrandmrsamos, the husband-and-wife team of writer Lee Tulloch and photographer Tony Amos, whose piece on the Harlem revival is just a taste of the treats that lie ahead. No ordinary travel writing, I can assure you. Anne Summers We are very proud to publish our first investigative special EDITOR & PUBLISHER report on Australia’s think tanks. Who are they? Who runs them? Who funds them? How accountable are they and how Stephen Clark much influence do they really have? In this landmark piece ART DIRECTOR of reporting, Robert Milliken uncovers how thinks tanks are Foong Ling Kong increasingly setting the agenda for the government. MANAGING EDITOR In other reports, you will meet Merryn Johns, the Australian woman making a splash as a magazine editor Wendy Farley in New York and who happens to be known as America’s Get Anne Summers DESIGNER Lesbian-in-Chief. -

The Secret Life of Elsie Curtin

Curtin University The secret life of Elsie Curtin Public Lecture presented by JCPML Visiting Scholar Associate Professor Bobbie Oliver on 17 October 2012. Vice Chancellor, distinguished guests, members of the Curtin family, colleagues, friends. It is a great honour to give the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library’s lecture as their 2012 Visiting Scholar. I thank Lesley Wallace, Deanne Barrett and all the staff of the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library, firstly for their invitation to me last year to be the 2012 Visiting Scholar, and for their willing and courteous assistance throughout this year as I researched Elsie Curtin’s life. You will soon be able to see the full results on the web site. I dedicate this lecture to the late Professor Tom Stannage, a fine historian, who sadly and most unexpectedly passed away on 4 October. Many of you knew Tom as Executive Dean of Humanities from 1999 to 2005, but some years prior to that, he was my colleague, mentor, friend and Ph.D. supervisor in the History Department at UWA. Working with Tom inspired an enthusiasm for Australian history that I had not previously known, and through him, I discovered John Curtin – and then Elsie Curtin, whose story is the subject of my lecture today. Elsie Needham was born at Ballarat, Victoria, on 4 October 1890 – the third child of Abraham Needham, a sign writer and painter, and his wife, Annie. She had two older brothers, William and Leslie. From 1898 until 1908, Elsie lived with her family in Cape Town, South Africa, where her father had established the signwriting firm of Needham and Bennett. -

Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 27Th November 2020

Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 27th November 2020 Sydney Opera House Bennelong Point Report Reference: 20164 Sydney Opera House – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 2020-11-27 - Revision 1 8 December 2020 Project Number: 20164 Version: Revision 1 Sydney Opera House 8 December 2020 Bennelong Point Revision 1 Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 27th November 2020 PREPARED BY: Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd ABN 61 614 634 525 Level 5, 73 Walker Street, North Sydney, 2060 Alex Danon Mob: +61 452 578 573 E: [email protected] www.pulseacoustics.com.au This report has been prepared by Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, and taking account of the timescale and resources allocated to it by agreement with the Client. Information reported herein is based on the interpretation of data collected, which has been accepted in good faith as being accurate and valid. This report is for the exclusive use of Sydney Opera House No warranties or guarantees are expressed or should be inferred by any third parties. This report may not be relied upon by other parties without written consent from Pulse Acoustic. Pulse Acoustic disclaims any responsibility to the Client and others in respect of any matters outside the agreed scope of the work. DOCUMENT CONTROL Reference Status Date Prepared Checked Authorised 20164 Sydney Opera House – Attended Construction Final 8th December Alex Danon Alex Danon Matthew Harrison Noise Measurements – 2020-11-27 - Revision 1 2020 Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd Page 2 of 21 Sydney Opera House 8 December 2020 Bennelong Point Revision 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... -

Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SENATE Official Hansard No. 15, 2002 MONDAY, 2 DECEMBER 2002 FORTIETH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—THIRD PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE INTERNET The Journals for the Senate are available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/work/journals/index.htm Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at: http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard SITTING DAYS—2002 Month Date February 12, 13, 14 March 11, 12, 13, 14, 19, 20, 21 May 14, 15, 16 June 17, 18, 19, 20, 24, 25, 26, 27 August 19, 20, 21, 22, 26, 27, 28, 29 September 16, 17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26 October 14, 15, 16, 17, 21, 22, 23, 24 November 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21 December 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM BRISBANE 936 AM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 729 AM DARWIN 102.5 FM FORTIETH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—THIRD PERIOD Governor-General His Excellency the Right Reverend Dr Peter Hollingworth, Companion of the Order of Australia, Officer of the Order of the British Empire Senate Officeholders President—Senator the Hon. Paul Henry Calvert Deputy President and Chairman of Committees—Senator John Joseph Hogg Temporary Chairmen of Committees—Senators Hon. Nick Bolkus, George Henry Brandis, Hedley Grant Pearson Chapman, John Clifford Cherry, Jacinta Mary Ann Collins, Hon. -

Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 25Th June 2021

Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 25th June 2021 Sydney Opera House Bennelong Point Report Reference: 20164 Sydney Opera House – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 2021-06-25 - Revision 1 28 June 2021 Project Number: 20164 Version: Revision 1 Sydney Opera House 28 June 2021 Bennelong Point Revision 1 Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 25th June 2021 PREPARED BY: Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd ABN 61 614 634 525 Level 5, 73 Walker Street, North Sydney, 2060 This report has been prepared by Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, and taking account of the timescale and resources allocated to it by agreement with the Client. Information reported herein is based on the interpretation of data collected, which has been accepted in good faith as being accurate and valid. This report is for the exclusive use of Sydney Opera House No warranties or guarantees are expressed or should be inferred by any third parties. This report may not be relied upon by other parties without written consent from Pulse Acoustic. Pulse Acoustic disclaims any responsibility to the Client and others in respect of any matters outside the agreed scope of the work. DOCUMENT CONTROL Reference Status Date Prepared Checked Authorised 20164 Sydney Opera House – Attended Construction Final 28th June 2021 Douglass Alex Danon Matthew Harrison Noise Measurements – 2021-06-25 - Revision 1 Harrison Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd Page 2 of 16 Sydney Opera House 28 June 2021 Bennelong Point Revision 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 4 2 SITE DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................................................... -

Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 2Nd February 2021

Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 2nd February 2021 Sydney Opera House Bennelong Point Report Reference: 20164 Sydney Opera House – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 2021-02-02 - Revision 1 11 February 2021 Project Number: 20164 Version: Revision 1 Sydney Opera House 11 February 2021 Bennelong Point Revision 1 Sydney Opera House (SOH) – Attended Construction Noise Measurements – 2nd February 2021 PREPARED BY: Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd ABN 61 614 634 525 Level 5, 73 Walker Street, North Sydney, 2060 Alex Danon Mob: +61 452 578 573 E: [email protected] www.pulseacoustics.com.au This report has been prepared by Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, and taking account of the timescale and resources allocated to it by agreement with the Client. Information reported herein is based on the interpretation of data collected, which has been accepted in good faith as being accurate and valid. This report is for the exclusive use of Sydney Opera House No warranties or guarantees are expressed or should be inferred by any third parties. This report may not be relied upon by other parties without written consent from Pulse Acoustic. Pulse Acoustic disclaims any responsibility to the Client and others in respect of any matters outside the agreed scope of the work. DOCUMENT CONTROL Reference Status Date Prepared Checked Authorised 20164 Sydney Opera House – Attended Construction Final 11th February Alex Danon Matthew Furlong Matthew Harrison Noise Measurements – 2021-02-02 - Revision 1 2021 Pulse Acoustic Consultancy Pty Ltd Page 2 of 21 Sydney Opera House 11 February 2021 Bennelong Point Revision 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... -

Luxury Lodges of Australia Brochure

A COLLECTION OF INDEPENDENT LUXURY LODGES AND CAMPS OFFERING UNFORGETTABLE EXPERIENCES IN AUSTRALIA’S MOST INSPIRING AND EXTRAORDINARY LOCATIONS luxurylodgesofaustralia.com.au LuxuryLodgesOfAustralia luxurylodgesofaustralia luxelodgesofoz luxelodgesofoz #luxurylodgesofaustralia 2 Darwin ✈ 19 8 4 6 8 10 15 ARKABA BAMURRU PLAINS5 Kununurra ✈ CAPELLA LODGE 10 CAPE LODGE Ikara-Flinders Ranges, South Australia Top End, Northern Territory Lord Howe Island, New South Wales ✈ CairnsMargaret River, Western Australia Broome ✈ 12 NORTHERN ✈ Hamilton Island TERRITORY 14 Exmouth ✈ 12 14 ✈ Alice Springs 16 QUEENSLAND 18 EL QUESTRO HOMESTEAD EMIRATES ✈ONE&ONLY Ayers Rock (Ulu ru) 9 LAKE HOUSE LIZARD ISLAND The Kimberley, Western Australia WESTERNWOLGAN VALLEY Daylesford, Victoria Great Barrier Reef, Queensland Luxury Lodges of Australia AUSTRALIABlue Mountains, New South Wales 17 A collection of independent luxury lodges and camps offering Brisbane ✈ unforgettable experiences in Australia’s most inspiring and SOUTH extraordinary locations. AUSTRALIA Australia’s luxury lodge destinations are exclusive by virtue of their 1 Perth ✈ 3 access to unique locations, people and experiences, and the small NEW SOUTH 20 22 24 26 number of guests they accommodate at any one time. Australia’s sun, WALES 6 11 Lord Howe Island ✈ LONGITUDE 131°4 MT MULLIGAN LODGE PRETTY BEACH HOUSE QUALIA sand, diverse landscapes and wide open spaces are luxuries of an 18 ✈ Ayers Rock (Uluru), Northern Territory Northern Outback, Queensland Sydney Surrounds, New South Wales GreatSydney