2016 Comprehensive Plan Northumberland County, Virginia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

Maryland's 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards

Maryland’s 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards EPA Approval Date: July 11, 2018 Table of Contents Overview of the 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards ............................................ 3 Nationally Recommended Water Quality Criteria Considered with Maryland’s 2016 Triennial Review ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Re-evaluation of Maryland’s Restoration Variances ...................................................................... 5 Other Future Water Quality Standards Work ................................................................................. 6 Water Quality Standards Amendments ........................................................................................... 8 Designated Uses ........................................................................................................................... 8 Criteria ....................................................................................................................................... 19 Antidegradation.......................................................................................................................... 24 2 Overview of the 2016 Triennial Review of Water Quality Standards The Clean Water Act (CWA) requires that States review their water quality standards every three years (Triennial Review) and revise the standards as necessary. A water quality standard consists of three separate but related -

Northumberland County, Virginia Shoreline Inventory Report

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 12-2014 Summary Tables: Northumberland County, Virginia Shoreline Inventory Report Marcia Berman Virginia Institute of Marine Science Karinna Nunez Virginia Institute of Marine Science Sharon Killeen Virginia Institute of Marine Science Tamia Rudnicky Virginia Institute of Marine Science Julie Bradshaw Virginia Institute of Marine Science See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Berman, M.R., Nunez, K., Killeen, S., Rudnicky, T., Bradshaw, J., Duhring, K., Stanhope, D., Angstadt, K., Tombleson, C., Procopi, A., Weiss, D. and Hershner, C.H. 2014. Northumberland County, Virginia - Shoreline Inventory Report: Methods and Guidelines, SRAMSOE no.444, Comprehensive Coastal Inventory Program, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, Gloucester Point, Virginia, 23062 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Marcia Berman, Karinna Nunez, Sharon Killeen, Tamia Rudnicky, Julie Bradshaw, Karen Duhring, David Stanhope, Kory Angstadt, Christine Tombleson, Alexandra Procopi, David Weiss, and Carl Hershner This report is available at W&M ScholarWorks: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports/784 -

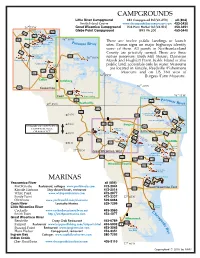

3-Fold Map.Cs2

CAMPGROUNDS Little River Campground 382 Campground Rd (VA 650) all (804) Smith Island Cruise www.chesapeakebaycampresort.com 453-3430 76o 35’W Great Wicomico Campground 836 Horn Harbor Rd (VA 810) 453-3351 White Point Glebe Point Campground 1895 VA 200 604 Marina 610 453-3440 Sandy Point 607 744 Marina Kinsale 608 76o 30’W 202 Yeocomico There are twelve public landings or launch River P 203 Port Kinsale otomac River Kinsale Harbor sites. Brown signs on major highways identify Marina some of them. All ponds in Northumberland 617 County are privately owned. There are three Hampton Hall Landing 624 o (being developed) Lewisetta 38 00’N nature preserves: Bush Mill Stream, Dameron Gardys Millpond Marina Marsh and Hughlett Point. Kohls Island is also Lodge Landing The Glebe Olversons public land, accessible only by water. Museums Marina are located in Kinsale, Reedville (Fishermens 712 623 Cod Creek 202 Coan River Museum) and on US 360 west of 76o 25’W 360 Burgess (Farm Museum). Callao Lottsburg Presley Creek 76o 20’W 360 Yeocomico Forrest Landing Hull Creek 612 Cubitt Creek Hacks Creek o Coan Rowes Landing 76 15’W Vir-Mar Beach 601 643 Potoma o c 37 55’N Heathsville River 360 648 201 Cockrells Railway 644 54’N 644 & Marina Kohls Island Ferry Little Wicomico River 650 Little River campground 53’N 707 639 Burgess 1 degree of latitude Smith Point = 360 651Marina 1 nautical mile, Cedar Point Landing 644 or 6080 feet 699 Little Wicomico 52’N Coopers Landing campgroundGlebe Point 652 Bush Mill Stream Great Wicomico 663 Sampsons Wharf campground -

TIPERS BRIDGE (Great Wicomico River Bridge) Spanning the Great

TIPERS BRIDGE HAER No. VA-58 (Great Wicomico River Bridge) Spanning the Great Wicomico River at Virginia State Route 200 at Glebe Point Kilmarnock Vicinity Northumberland County Virginia PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service Northeast Region Philadelphia Support Office U.S. Custom House 200 Chestnut Street © Philadelphia, PA 19106 tL HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD TIPERS BRIDGE (Great Wicomico River Bridge) HAER No. VA-58 Location: Spanning the Great Wicomico River on Virginia State Route 200 at Glebe Point Kilmarnock Vicinity Northumberland County Virginia USGS Reedville Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: 18.378360. 4189550 Fabricator: Virginia Bridge and Iron Company of Roanoke, Virginia Date of Construction: July through December 1934 Present Owner: Virginia Department of Transportation 1401 East Broad Street Richmond, Virginia 23219 Present Use: Vehicular Bridge Significance: Built in six months during the depth of the Depression, the Tipers Bridge is a well preserved example of a once standard bridge type that was commonly used to economically span a large number of major river crossings in the Virginia Tidewater. It is located at a crossing that has a long history of some economic importance in Northumberland and Lancaster Counties. This is the second oldest of ten remaining swing- spans dating from between 1930 and 1957 currently listed in the Virginia Department of Transportation bridge inventory. Project Information: This documentation was undertaken in May 1991 under contract with the Virginia Department of Transportation as a mitigative measure prior to the removal and disposal of the bridge. Luke H. Boyd Architectural Historian Archaeological Research Center Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia Tipers Bridge (Great Wicomico River Bridge) HAER No. -

Citations Year to Date Printed: Tuesday April 17 2018 Citations Enterd in Past 7 Days Are Highlighted Yellow

Commonwealth of Virginia - Virginia Marine Resources Commission Lewis Gillingham, Tournament Director - Newport News, Virginia 23607 2017 Citations Year To Date Printed: Tuesday April 17 2018 Citations Enterd in Past 7 Days Are Highlighted Yellow Species Caught Angler Address Release Weight Lngth Area Technique Bait 1 AMBERJACK 2017-09-09 ROBBIE BRYAN VIRGINIA BEACH, VA Y 50 SOUTHERN TOWER (NAVY JIGGING LURE(UNSPECIFIED) 2 BLACK DRUM 2017-10-22 MCKENZIE LEWIS GLOUCESTER, VA Y 52 BACK RIVER ARTIFICIA BAIT FISHING CRAB, UNSPECIFIED 3 BLACK DRUM 2017-10-09 WALTER SCOTT, JR. SMITHFIELD, VA Y 49 664 BRIDGE TUNNEL; M BAIT FISHING CRAB, PEELER OR SOFT 4 BLACK DRUM 2017-10-09 LEWIS RICHARDSON NEWPORT NEWS, VA N 81 lbs 664 BRIDGE TUNNEL; M BAIT FISHING CRAB, PEELER OR SOFT 5 BLACK DRUM 2017-10-09 WALTER E. SCOTT, SR. SMITHFIELD, VA Y 48 664 BRIDGE TUNNEL; M BAIT FISHING CRAB, PEELER OR SOFT 6 BLACK DRUM 2017-09-17 CURT SELLARD LANCASTER, PA Y 46 CHESAPEAKE BAY - UNS BAIT FISHING CRAB, UNSPECIFIED 7 BLACK DRUM 2017-07-08 TIM DAVIDSON POWHATAN, VA Y 47 CBBT HIGH LEVEL BRID BAIT FISHING CLAM 8 BLACK DRUM 2017-05-23 WILLIAM JAMES PAPPAS VIRGINIA BEACH, VA Y 49 OFF VA BEACH, INSHOR BAIT FISHING BAIT (UNSPECIFIED) 9 BLACK DRUM 2017-05-22 RICHARD RANG BLOXOM, VA Y 50.5 HOG ISLAND BAY BAIT FISHING BAIT (UNSPECIFIED) 10 BLACK DRUM 2017-05-19 RAY WILLETT PARKSLEY, VA Y 50 OFF FISHERMAN ISL. S BAIT FISHING CRAB, UNSPECIFIED 11 BLACK DRUM 2017-05-16 SAMUEL R. -

Northern Neck of Virginia Historical Magazine

§aA,SE’8433/1'7 47‘.1Ta. 59- 1199772» M0Y‘i'” '\& ~ C; N 1311 N k t . y . ‘Q . § of V1rgm1a Q ’ Historical “ . ‘I 0 5 I\. Ma gaz1nc <~ ’ l ( ‘ DECEMBER,1960 .\. ‘I’ ‘x’ . 3, VOL. X No. 1 5 .\I. ii ‘i '\ Reportof the ActingPresident 863 «; The Cavalier. ThomaxLomaxHunter 865 ' _ “Virginiana” for Posterity. Ross Valentine 867 _ ’ § The Old Pope’s Creek Church Site. Treadwell Davixon ........................................................869 i ' ‘\’ Captain John Haynie 872 4 ‘ ‘ / The Lost Settlement of Queenstown. iames Wharton ...............................................................875 \ _ &, ' OldExeter Famham LodgeAmong Plantation. Most 7ames Interesting Motley Virginia Booker, Shrines. M.D .............................................................883 Addie V. Payne...............880 . ' _ .\; Northern Neck Epitaphs. Miriam Haynie 899 .1, - I A Reminder to the Historical Society 901 ‘ & Memorialto Robert Opie Norris,Jr 903 § ' \ A History of Menhaden Industry in Virginia 910 1 I ‘} Miscellaneous Legislative Petitions 925 ‘\' . Q_ ' EleventhGaskinsMemorialTablet Annual Meeting 94.5939 ‘.§ . (\, Membership List 948 {, / In Memoriam 958 \ ' ; Published Annually by g, ‘ -{ THE NORTHERN NECK ofVIRGINIA ‘, " - HISTORICAL SOCIETY A MONTROSS, Westmoreland County, VIRGINIA 4<» - {, Sacramenlo Brandi fienealogical Library NORTHERN NECK OF VIRGINIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY MONTROSS. WESTMOREIAND COUNTY, VIRGINIA '8? Officers SENATOR R. O. NORRIS, JR., Lively, Virginia President Mu. Tnoiuis L. Human, King George,Virginia Secretary Miss Lucy BRowNBun, Hague, Virginia Histarian F. F. CHANDLER,Montross, Virginia Treasurer Mas. F. F. CHANDILR,Montross, Virginia ‘ Executive Assistant C. F. UNRu1-1 MRS. LOUISE S'I'auAR'r BJORNSSON BEVERLEYBRouN Kinsale, Virginia State of Colorado State of West Virginia Mas. E. Huoi-I Surm A. MAXCoi>rAoIs MR5. Jusns MAcMuLi.aN Heathsville, Virginia State of Missouri State of New Jersey MR3. -

7. Wild and Scenic Rivers

7. Wild and Scenic Rivers Virginia Wild and Scenic Rivers Designation NEPAassist Maps Distance to Closest Wild and Scenic Rivers Downstream – Bluestone River WV Upstream – New River (So. Fork) NC New River Wild and Scenic River Study Executive Summary of Findings [2009] NEPAssist Map Distance by Direct Route NEPAssist Map Distance by Water Route Nationwide Rivers Inventory Inventory for Virginia NEPAssist Maps Distance to Little River Downstream by Direct Route Downstream by Water Route NEPAssist Maps Distance to Big Reed Island Crk Downstream by Direct Route Downstream by Water Route VA CDBG #15-15 Pulaski Kersey Bottom / Case Knife Road Revitalization Project Environmental Review Record 12/17/2015 Virginia HOME NATIONAL SYSTEM MANAGEMENT RESOURCES PUBLICATIONS CONTACT US KID'S SITE VIRGINIA Virginia has approximately 49,350 miles of river, but no designated wild & scenic rivers. Virginia does not have any designated rivers. Virginia Go Choose A River Go While progress should never come to a halt, there are many places it should never come to at all. — Paul Newman NATIONWIDE RIVERS INVENTORY KID'S SITE CONTACT US PRIVACY NOTICE Q & A SEARCH ENGINE SITE MAP http://www.rivers.gov/virginia.php 1/2 12/17/2015 NEPAssist NEPAssist Measure Find address or place Print Basemap Imagery Measure Draw Erase Identify | Miles 37.705532, 79.542102 + Measurement Result 39.5 Miles – 0 10 20mi The project area is located approximately 39.5 miles (direct route) from the location where the Bluestone River, a designated Wild and Scenic River in West Virginia, flows into the New River. The project area is located on Peak Creek, which flows into the New River upstream from this point where the Bluestone River flows into the New River. -

English Duplicates of Lost Virginia Records

T iPlCTP \jrIRG by Lot L I B RAHY OF THL UN IVER.SITY Of ILLINOIS 975.5 D4-5"e ILL. HJST. survey Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/englishduplicateOOdesc English Duplicates of Lost Virginia Records compiled by Louis des Cognets, Jr. © 1958, Louis des Cognets, Jr. P.O. Box 163 Princeton, New Jersey This book is dedicated to my grandmother ANNA RUSSELL des COGNETS in memory of the many years she spent writing two genealogies about her Virginia ancestors \ i FOREWORD This book was compiled from material found in the Public Record Office during the summer of 1957. Original reports sent to the Colonial Office from Virginia were first microfilmed, and then transcribed for publication. Some of the penmanship of the early part of the 18th Century was like copper plate, but some was very hard to decipher, and where the same name was often spelled in two different ways on the same page, the task was all the more difficult. May the various lists of pioneer Virginians contained herein aid both genealogists, students of colonial history, and those who make a study of the evolution of names. In this event a part of my debt to other abstracters and compilers will have been paid. Thanks are due the Staff at the Public Record Office for many heavy volumes carried to my desk, and for friendly assistance. Mrs. William Dabney Duke furnished valuable advice based upon her considerable experience in Virginia research. Mrs .Olive Sheridan being acquainted with old English names was especially suited to the secretarial duties she faithfully performed. -

Understanding the Role of Stylochus Ellipticus As a Predator of Crassostrea Virginica in Chesapeake Bay Tributaries

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Understanding the role of Stylochus ellipticus as a predator of Crassostrea virginica in Chesapeake Bay tributaries Marion Kensey Barker Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/599 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Marion Kensey Barker May 2014 All Rights Reserved UNDERSTANDING THE ROLE OF STYLOCHUS ELLIPTICUS AS A PREDATOR OF CRASSOSTREA VIRGINICA IN CHESAPEAKE BAY TRIBUTARIES A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at Virginia Commonwealth University by M. KENSEY BARKER B.S. Virginia Commonwealth University 2010 Director: Bonnie L. Brown, PhD, Department of Biology Committee: Edward L. Boone, PhD, Department of Statistical Sciences and Operations Research Alaina Hart Campbell, MS, Department of Biology J. M. Clint Turbeville, PhD, Department of Biology Karen M. Kester, PhD, Department of Biology Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2014 Acknowledgement I am eternally grateful to the people in my life who have offered their guidance and support to me during this project. First of all, I thank my dear friend, roommate and cousin, Chelsea. Her support has been paramount to my success throughout this project. My advisor, Dr. Bonnie Brown, gave me the independence and intellectual stimulation I needed to find my bearings in academia. -

VIRGINIA WORKING WATERFRONT MASTER PLAN Guiding Communities in Protecting, Restoring and Enhancing Their Water-Dependent Commercial and Recreational Activities

VIRGINIA WORKING WATERFRONT MASTER PLAN Guiding communities in protecting, restoring and enhancing their water-dependent commercial and recreational activities September 2016 This planning report, Task 92 was funded by the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program at the Department of Environmental Quality through Grant #NA15NOS4190164 of the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA, or any of its subagencies. 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction .......................................................................................... 4 II. Acknowledgements .............................................................................. 6 III. Executive Summary .............................................................................. 8 IV. Working Waterfronts – State of the Commonwealth....................... 20 V. Northern Neck Planning District Commission ................................... 24 A. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 24 B. History of Working Waterfronts in the Region .................................................... 26 C. Current Status of Working Waterfronts in the Region ........................................ 28 D. Working Waterfront Project Background ........................................................... -

VIRGINIA WORKING WATERFRONT MASTER PLAN Guiding Communities in Protecting, Restoring and Enhancing Their Water-Dependent Commercial and Recreational Activities

VIRGINIA WORKING WATERFRONT MASTER PLAN Guiding communities in protecting, restoring and enhancing their water-dependent commercial and recreational activities JULY 2016 This planning report, Task 92 was funded by the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program at the Department of Environmental Quality through Grant #NA15NOS4190164 of the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA, or any of its subagencies. 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 4 II. Acknowledgements ......................................................................................... 6 III. Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 8 IV. Working Waterfronts – State of the Commonwealth ................................. 20 V. Northern Neck Planning District Commission ............................................. 24 A. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 25 B. History of Working Waterfronts in the Region .......................................................................... 26 C. Current Status of Working Waterfronts in the Region.............................................................