UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

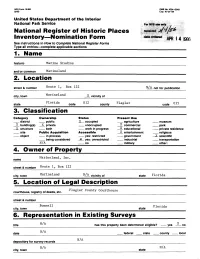

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (M2) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Marine Studios and/or common Marineland 2. Location street & number Route *» Box 122 N/A not for publication city, town Marineland JL vicinity of Florida 012 state code county code 035 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public J£ _ occupied agriculture museum X buiiding(s) X private unoccupied x commercial park X structure both work in progress x educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible X entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government _ X_ scientific being considered * yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A no military other; 4. Owner off Property Marineland, Inc. name street & number Route X » Box 122 city, town Marineland N/A vicinity of state Florida 5. Location off Legal Description Flagler County Courthouse courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. street & number Bunnell Florida city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Surveys V title N/A has this property been determined eligible? __ yes no date N/A federal state N/A depository for survey records N/A N/A city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one X excellent deteriorated unaltered _ X_ original site good . ruins X altered moved date fair unex posed Describe the'present and original (if known) physical appearance Marineland, originally called Marine Studios, is located on a narrow strip of land between the Atlantic Ocean and the Intercoastal Highway in the incorporated municipality of Marineland, which straddles the St. -

Views of Dolphins

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Humandolphin Encounter Spaces: A Qualitative Investigation of the Geographies and Ethics of Swim-with-the-Dolphins Programs Kristin L. Stewart Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES HUMAN–DOLPHIN ENCOUNTER SPACES: A QUALITATIVE INVESTIGATION OF THE GEOGRAPHIES AND ETHICS OF SWIM-WITH-THE-DOLPHINS PROGRAMS By KRISTIN L. STEWART A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Geography in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded Spring Semester, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Kristin L. Stewart All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Kristin L. Stewart defended on March 2, 2006. ________________________________________ J. Anthony Stallins Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________________ Andrew Opel Outside Committee Member ________________________________________ Janet E. Kodras Committee Member ________________________________________ Barney Warf Committee Member Approved: ________________________________________________ Barney Warf, Chair, Department of Geography The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Jessica a person, not a thing iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to all those who supported, encouraged, guided and inspired me during this research project and personal journey. Although I cannot fully express the depth of my gratitude, I would like to share a few words of sincere thanks. First, thank you to the faculty and students in the Department of Geography at Florida State University. I am blessed to have found a home in geography. In particular, I would like to thank my advisor, Tony Stallins, whose encouragement, advice, and creativity allowed me to pursue and complete this project. -

Ridgway, S. H. (1995A)

Aquatic Mammals 2008, 34(3), 471-513, DOI 10.1578/AM.34.3.2008.471 Historical Perspectives Sam H. Ridgway (born 26 June 1936 ) Dr. Sam Ridgway is one of the founders of mentored are now in zoological institutions, on mammal medicine. He completed a large share university faculty, in the military (one is a General of the seminal work in marine mammal medicine, Officer), in government employment, and one is and he continues to promote both applied and an astronaut. Dr. Ridgway is an elected Fellow of basic research in the field of marine mammalogy. the Acoustical Society of America for his stud- He has published over 260 papers, book chapters, ies on hearing of marine mammals and also is a and books, including one of the most definitive Fellow of the American College of Zoological works on marine mammals, Mammals of the Sea Medicine for his work on marine mammal medi- (1972). Much of his work has examined mamma- cine. In 2008, the Acoustical Society of America lian bioacoustics with a focus on dolphin auditory honored Dr. Ridgway at their 156th conference physiology and echolocation. Dr. Ridgway and in Miami, Florida, with 24 special presentations the late Dr. Kenneth Norris share the high distinc- on his work over the past 40 years. Other awards tion of being viewed as the founders of dolphin include the Distinguished Alumnus Award, Texas physiology and medicine. A&M University, College of Veterinary Medicine; Dr. Ridgway earned his Bachelor of Science the Lifetime and Clinical Medicine Awards from (1958) and Doctor of Veterinary Medicine the International Association for Aquatic Animal degrees (1960) from Texas A&M University. -

JUN 1 41976 Ii

AtJSEMENTr PARKS - A REIEVANT FORM OF PUBLIC RECREATION by BRITIMARI WIUND Baccalaureate, Enskilda Gymasiet, Stockholm (1969) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIP-1ENTS FOR THE DBX=Es OF MASTER OF ARCHITCTURE at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1976 Signature of Author. / -- Department of Architecture May 11, 1976 Certified by....... Tunney Lee, Associate Professor Thesis supervisor Accepted by......................................................... Michael Underhill, Chairman, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students Rotcn JUN 1 41976 ii AMUSEMENT PARKS - A RELEVANT FORM OF PUBLIC RECRFATION Brittmari Wilund Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 11, 1976 in partial fulfillment of the requiremrents for the degree of Master of Architecture At every point in history there has been something which the enterprising American businessman could capitalize on, from the Puritan work ethic, the prudishness of the Victorian era, and the new industrial workers' quest for self education, to the increased nobility and the separation of homej work, and recreation created by the acceleration of the capitalist economy and the creation of the interstate highway system. A few forms of commercial recreation have been dealt with in this thesis, concentrating on the development of amusement parks, from the first pic- nic parks built by the traction companies and others in order to increase the use of their particular means of transportation through the develop- ment of traditional amusement parks which we see today on the edges of met- ropolitan areas struggling against the forces of rising property prices and declining business, to the advent of Disneyland and the beginning of a new era in the history of amusement parks - the theme parks. -

2019 Accreditation Inspector of the Year

2019 Accreditation Inspector of the Year Greg Charbeneau : Operations Vice President/General Manager, OdySea Aquarium Greg Charbeneau is the Vice President and General Manager at OdySea Aquarium, where he oversees operations at OdySea in the Desert in Scottsdale, Arizona. Greg was responsible for the establishment of the Southwest’s largest public aquarium and participates in the development and management of other projects within the overarching company. He worked his way through the ranks on the animal side of the profession while learning the business aspects which led him to his current position. Greg has worked at multiple nationally acclaimed aquariums, theme parks, and resorts throughout his 32 year career. He has managed both established, complex operations and large start-up operations. Mr. Charbeneau is an active participant in various conservation and education initiatives and has served as an AZA accreditation inspector since 2011. 2019 Accreditation Inspector of the Year David Hagan : Animal Management/Husbandry Curator, Indianapolis Zoo For three decades, David Hagan has had a remarkable impact on the Indianapolis Zoo. As Curator, he is responsible for the African plains and animal encounters biomes, which includes all bird and felid species at the zoo. David’s lifelong love of animals began as a child when he joined an explorer scout post at the Louisville Zoo. There, he was able to volunteer in the animal department, which led to years of volunteer service at Louisville Zoo through high school and college. David received his degree in Biology from Eastern Kentucky University. His first full- time position was as an animal keeper at the Indianapolis Zoo. -

Let Stanley Park Be!

Just Say No! Let Stanley Park Be! PROTECT NATURE: Stanley Park Let Stanley Park Be! Lifeforce/Peter Hamilton Copyright Report to: Vancouver Parks Board Commissioners Mayor Sam Sullivan and Vancouver Council Compiled by: Lifeforce Foundation, Box 3117, Vancouver, BC, V6B 3X6, (604)669-4673; [email protected]; www.lifeforcefoundation.org November 25, 2006 Introduction The Aquarium and Zoo Industry sends anti-conservation messages to get up close with wildlife. Touch, feed and swim with business gimmicks promotes a speciest attitude to dominate and control wildlife. People, Animals and Ecosystems Threatened by Captivity Plans People, animals and ecosystems would be threatened if the Vancouver Aquarium expands again. More animals would be imprisoned and scarce Stanley Park land would be destroyed. The new prisons will costs taxpayers millions of dollars that should be spent on essential services social and environmental protection. The 50th Anniversary of the Vancouver Aquarium marks a legacy of animal suffering. They started the orca slave trade when one orca briefly survived their attempt to harpoon him to use as a model for a sculpture. The resulting removal of 48 Southern Community Orcas decimated their families. There has been at least 29 deaths of cetaceans and numerous other death and suffering of wildlife. The expansion is sad news because imprisonment of sentient creatures will continue. When the beluga pool was enlarged the promise was that it would be for three but when one died they capture three more. The overcrowding and abnormal aggression lead to some being warehoused in a 50-foot pool for over two years out of public view. -

Selling Sunshine: How Cypress Gardens Defined Florida, 1935-2004

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2009 Selling Sunshine: How Cypress Gardens Defined Florida, 1935-2004 David Dinocola University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Dinocola, David, "Selling Sunshine: How Cypress Gardens Defined Florida, 1935-2004" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4081. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4081 SELLING SUNSHINE: HOW CYPRESS GARDENS DEFINED FLORIDA, 1935-2004 by DAVID CHARLES DINOCOLA II B.A. University of Central Florida, 2005 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2009 i © 2009 David Dinocola ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the relationship between Cypress Gardens and the state of Florida. Specifically, it focuses on how the creator of the park, Dick Pope, created his park after his own idealized vision of the state, and how he then promoted both his park and Florida as one and the same. The growth and later decline of Cypress Gardens follows trends in Florida’s growth patterns and shifts in tourism. This study primarily uses a combination of newspaper sources and promotional pictures and other media from the park to explain how Pope attempted to make Cypress Gardens synonymous with Florida. -

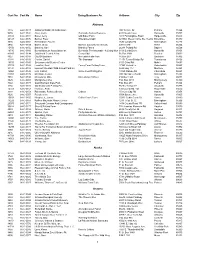

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 3316 64-C-0117 Alabama Wildlife Rehabilitation 100 Terrace Dr Pelham 35124 9655 64-C-0141 Allen, Keith Huntsville Nature Preserve 431 Clouds Cove Huntsville 35803 33483 64-C-0181 Baker, Jerry Old Baker Farm 1041 Farmingdale Road Harpersville 35078 44128 64-C-0196 Barber, Peter Enterprise Magic 621 Boll Weevil Circle Ste 16-202 Enterprise 36330 3036 64-C-0001 Birmingham Zoo Inc 2630 Cahaba Rd Birmingham 35223 2994 64-C-0109 Blazer, Brian Blazers Educational Animals 230 Cr 880 Heflin 36264 15456 64-C-0156 Brantley, Karl Brantley Farms 26214 Pollard Rd Daphne 36526 16710 64-C-0160 Burritt Museum Association Inc Burritt On The Mountain - A Living Mus 3101 Burritt Drive Huntsville 35801 42687 64-C-0194 Cdd North Central Al Inc Camp Cdd Po Box 2091 Decatur 35602 3027 64-C-0008 City Of Gadsden Noccalula Falls Park Po Box 267 Gadsden 35902 41384 64-C-0193 Combs, Daniel The Barnyard 11453 Turner Bridge Rd Tuscaloosa 35406 19791 64-C-0165 Environmental Studies Center 6101 Girby Rd Mobile 36693 37785 64-C-0188 Lassitter, Scott Funny Farm Petting Farm 17347 Krchak Ln Robertsdale 36567 33134 64-C-0182 Lookout Mountain Wild Animal Park Inc 3593 Hwy 117 Mentone 35964 12960 64-C-0148 Lott, Carlton Uncle Joes Rolling Zoo 13125 Malone Rd Chunchula 36521 22951 64-C-0176 Mc Wane Center 200 19th Street North Birmingham 35203 7051 64-C-0185 Mcclelland, Mike Mcclellands Critters P O Box 1340 Troy 36081 3025 64-C-0003 Montgomery Zoo P.O. -

University of Florida Herbarium (FLAS) Macroalgae Collection: an Overview

University of Florida Herbarium (FLAS) Macroalgae Collection: An Overview 26 October 2015 Carol Ann McCormick*, Robert Kevan Schoonover, William Marinello, and Liane Salgado University of North Carolina Herbarium (NCU) * corresponding author [email protected] In 2013 the National Science Foundation funded The Macroalgal Herbarium Consortium: Accessing 150 Years of Specimen Data to Understand Changes in the Marine/Aquatic Environment. The Consortium consists of forty-nine herbaria, and the label data and images of specimens held by these herbaria are available to the public and to researchers at macroalgae.org. The University of North Carolina Herbarium (NCU) is a regional hub for the Macroalgal Consortium, so in addition to cataloging our collection, we are also cataloging collections from the University of Florida (FLAS), Louisiana State University (LSU), Texas A&M (TAES), the University of Alabama (UNA), the University of South Carolina (USCH), and the University of North Carolina at Wilmington (WNC). NCU received the University of Florida (FLAS) macroalgae collections in February, 2015 and Kevan Schoonover (UNC-Chapel Hill undergrad, William Marinello (NCU staff), and Anne Vanarsdall (NCU volunteer) imaged the specimens. The specimens were returned to FLAS on 29 April, 2015. NCU Herbarium staff members Liane Salgado and Carol Ann McCormick completed transcribing label data and georeferencing specimens on 16 June, 2015. The University of Florida Herbarium (FLAS) curates ca. 470,000 specimens of fungi, lichens, algae, bryophytes, and vascular plants. In 2013 Kent Perkins, FLAS collection manager, estimated the macroalgae collection to be ca. 2,000 specimens. A total of 3,067 macroalgal specimens were cataloged for the Project. -

The Case Against MARINE MAMMALS in CAPTIVITY

The Case Against MARINE MAMMALS IN CAPTIVITY ANIMAL WELFARE INSTITUTE + WORLD ANIMAL PROTECTION The Case Against MARINE MAMMALS IN CAPTIVITY Authors: Naomi A. Rose, Ph.D. and E.C.M. Parsons, Ph.D. Editor: Dave Tilford • Designer: Alexandra Alberg Prepared on behalf of the Animal Welfare Institute and World Animal Protection This report should be cited as: Rose, N.A. and Parsons, E.C.M. (2019). The Case Against Marine Mammals in Captivity, 5th edition (Washington, DC: Animal Welfare Institute and World Animal Protection), 160 pp. TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 List of Acronyms and Abbreviations 60 Chapter 8 • Cetacean Intelligence 3 Overview 65 Chapter 9 • Mortality and Birth Rates 66 Non-cetaceans 6 Introduction 67 Bottlenose Dolphins 68 Orcas 9 Chapter 1 • Education 70 Other Cetacean Species 70 Summary 14 Chapter 2 • The Conservation/ Research Fallacy 72 Chapter 10 • Human–Dolphin Interactions 16 Species Enhancement Programs 72 Dolphin-Assisted Therapy 18 Mixed Breeding and Hybrids 73 Swim-With-Dolphin Attractions 18 Captive Cetaceans and Culture 75 Petting Pools and Feeding Sessions 20 The Public Display Industry Double Standard 77 Chapter 11 • Risks to Human Health 22 Ethics and Captive Breeding 77 Diseases 22 Stranding Programs 78 Injury and Death 23 Research 83 Chapter 12 • The Blackfish Legacy 26 Chapter 3 • Live Captures 83 Blackfish 31 Bottlenose Dolphins 85 The Blackfish Effect 33 Orcas 87 The Legal and Legislative Impacts of 35 Belugas Blackfish 88 The End of Captive Orcas? 37 Chapter 4 • The Physical and Social Environment 89 Seaside Sanctuaries: -

GUEST INTERACTION with ASIAN SMALL CLAWED OTTERS (Aonyx Cinerea)

Volume 37, Number 4 ~ Fourth Quarter 2012 Magazine of the International Marine Animal Trainers’ Association AN INNOVATIVE APPROACH TO TRAINING GUEST INTERACTION WITH ASIAN SMALL CLAWED OTTERS (Aonyx cinerea) ALSO IN THIS CARE AND HANDLING OF ISSUE: NEONATE BOTTLENOSE DOLPHINS ISSN # 1007-016X DEDICATED TO ADVANCING THE HUMANE CARE AND HANDLING OF MARINE ANIMALS BY FOSTERING COMMUNICATION BETWEEN PROFESSIONALS THAT SERVE MARINE ANIMAL SCIENCE THROUGH TRAINING, PUBLIC DISPLAY, RESEARCH, HUSBANDRY, CONSERVATION, AND EDUCATION. Front Cover Photo Credit: Valerie Greene IMATA BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESIDENT PAST PRESIDENT SHELLEY WOOD MICHAEL OSBORN ABC Animal Training Mystic Aquarium REGIONAL REPORTER CONTACT INFORMATION Dolphin Discovery Associate Editor: Nicole O’Donnell [email protected] TREASURER Associate Editor: Martha Hill [email protected] FIRST VICE PRESIDENT PATTY SCHILLING Asia: Philip Wong [email protected] GRANT ABEL New England Aquarium Australia/New Zealand: Ryan Tate [email protected] Ocean Park Hong Kong Canada: Brian Sheehan [email protected] SECRETARY SECOND VICE PRESIDENT JENNIFER LEACH Caribbean Islands: Adrian Penny [email protected] MICHELLE SOUSA SeaWorld San Diego Europe North Central: Christiane Thiere [email protected] Aquarium of the Pacific Europe Northeast: Sunna Edberg [email protected] DIRECTOR-AT-LARGE Europe Northwest: John-Rex Mitchell [email protected] THIRD VICE PRESIDENT LAURA YEATES Europe South Central: Pablo Joury [email protected] KELLY FLAHERTY CLARK National -

Whalewatcher 2020 • Vol

Journal of the American Cetacean Society WHALEWATCHER 2020 • VOL. 43 • NO. 1 BREAKING THE SURFACE WOMENOFCETOLOGY Humpback calf. Photo by Jo Marie Acebes. Editorial Pod ACS National Board of Directors LEAD EDITOR Read about our Board Members at Sabena Siddiqui acsonline.org ASSISTANT EDITORS PRESIDENT Diane Glim Uko Gorter Uko Gorter SECRETARY On the Cover Kelsey Stone Diane Glim The Caldwells recording PRODUCTION ARTIST TREASURER vocalizations of a Rose Freidin Ric Matthews bottlenose dolphin at Marineland of Florida. Shelby Kasberger, Conservation Chair Photo by: Marineland of Florida Joy Primrose Sabena Siddiqui, Student Chair AMERICAN CETACEAN SOCIETY Kelsey Stone, Social Media Manager P.O. Box 51691 Jayne Vanderhagen Pacific Grove, CA 93950 Bob Wilson acsonline.org ACS Team Members Kara Henderlight, Advocacy Chair 2 BREAKING THE SURFACE WOMEN OF CETOLOGY Letter from the President Uko Gorter ou may have noticed that this special We thought it was high time to look back I want to express my gratitude to our ACS issue of our Whalewatcher journal is and see how far women have come in the National Board Member, Sabena Siddiqui, not really about whales. Instead, it is field of cetology, or the study of whales. We who served as our lead Editor for this Yabout humans. Women, to be more precise. also wanted to hear from women scientists wonderful issue. Sabena has deftly guided who are working in the field today, or the process with immense patience and For anyone who has attended a marine recently retired. The results are essays from sensitivity. It is because of her efforts, mammal science conference recently, a wonderful mix of women from different while still navigating her own academic you would have immediately noticed the generations, backgrounds, and career work, that this unique special issue has multitude of women in attendance.