UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bionicle: Journey's

BIONICLE: JOURNEY’S END Compiled for usage on Brickipedia © 2010 The LEGO Group. LEGO, the LEGO logo, and BIONICLE® are trademarks of the LEGO Group. All Rights Reserved. Over 100,000 years ago … Angonce walked purposefully toward a blank stone wall in the rear of his chamber. As the tall, spare figure approached, the blocks that made up the wall softened and shifted, forming an opening. He gazed out this new window at the mountains and forest below, sadness and regret in his dark eyes. He had often stood here before, reflecting upon the beauty of Spherus Magna. From the southern desert of Bara Magna to the great northern forest, it was a place of stunning vistas and infinite opportunities for knowledge. Angonce had spent most of his life discovering its mysteries, and had hoped for many more years in the pursuit. But now it seemed that was not to be. He had run every test that he could think of, and checked and rechecked his findings. They always came out the same: Spherus Magna was doomed. How did it come to this? Angonce wondered. How did we let it get so far? He, his brothers and sisters were scholars. Their theories, discoveries and inventions had transformed this world and changed the lives of the inhabitants, the Agori, in many ways. In gratitude, they had long ago been proclaimed rulers of Spherus Magna. The Agori called them the “Great Beings.” But the business of running a world – settling disputes, managing economies, dealing with defense issues, worrying about food and equipment supplies – all of this the Great Beings found a distraction. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Capturing That Solid-Gold Nugget

Chapter 1 Capturing That Solid-Gold Nugget In This Chapter ▶ Gathering song ideas from anywhere ▶ Organizing and tracking your thoughts and inspirations ▶ Documenting your ideas his book is for everyone who shares the dream of harnessing the song- Twriting power we all have within. You’ve come to the right place if your heart keeps telling you to write a song, but your mind is uncertain as to the process of the craft or what’s required to create a really good song. You bought the right book if you’re wondering how to collect and organize your ideas. You have found the right resource if you have pieces of songs lying in notebooks and on countless cassettes but can’t seem to put the pieces together. This book is for you if you have racks of finished song demos but don’t know what to do next to get them heard. When you know the elements that make up a great song and how the pros go about writing one, you can get on the right path to creating one of your own. Unless you’re lucky enough to have fully finished songs come to you in your deepest dreams, or to somehow take dictation from the ghosts of Tin Pan Alley (the publishing area located in New York City in the 1930s and 1940s), most of us need to summon the forces, sources, reasons, and seasons that give us the necessary motivation to draw a song from our heart of hearts. Given that initial spark, you then need the best means of gathering those ideas, organizing them, putting them into form, and documenting them as they roll COPYRIGHTEDin — before it’s too late and they MATERIAL roll right out again! Have you ever noticed how you can remember a powerful dream just after you’ve awakened only for it to vanish into thin air in the light of day? Song ideas can be just as illusive. -

Hundreds of Country Artists Have Graced the New Faces Stage. Some

314 performers, new face book 39 years, 1 stage undreds of country artists have graced the New Faces stage. Some of them twice. An accounting of every one sounds like an enormous Requests Htask...until you actually do it and realize the word “enormous” doesn’t quite measure up. 3 friend requests Still, the Country Aircheck team dug in and tracked down as many as possible. We asked a few for their memories of the experience. For others, we were barely able to find biographical information. And we skipped the from his home in Nashville. for Nestea, Miller Beer, Pizza Hut and “The New Faces Show had Union 76, among others. details on artists who are still active. (If you need us to explain George Strait, all those radio people, and for instance, you’re probably reading the wrong publication.) Enjoy. I made a lot of friends. I do Jeanne Pruett: Alabama native Pruett remember they had me use enjoyed a solid string of hits from the early the staff band, and I was ’70s right into the ’80s including the No. resides in Nashville, still tours and will suffering some anxiety over not being able 1 smash, “Satin Sheets.” Pruett is based receive a star in the Hollywood Walk of to use my band.” outside of Nashville and is still active as a 1970 Fame in October, 2009. performer and as a member of the Grand Jack Barlow: He charted with Ole Opry. hits like “Baby, Ain’t That Love” Bobby Harden: Starting out with his two 1972 and “Birmingham Blues,” but by sisters as the pop-singing Harden Trio, Connie Eaton: The Nashville native started Mel Street: West Virginian Street racked the mid-’70s Barlow had become the nationally Harden cracked the country Top 50 back her country career as a teenager and hit the up a long string of hits throughout the ’70s, famous voice of Big Red chewing gum. -

I Nmates Find Redemption Through Songjeni DOMINELLI

“Hear Our Cries” I nmates Find Redemption Through Song JENI DOMINELLI 8 | JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2019 AMERICANJails His name is Quincy, and he is a pre-trial detainee in the jail, awaiting a new trial after his prison sentence was overturned. People call him Q. When I meet him, I tell him that he’s got the best name for the entertainment industry. He flashes me a megawatt smile—the bright- est kind where his eyes and entire being smile. He is 26 years old and has a vibrant personality and upbeat spirit. Already incarcerated for seven years, Quincy has somehow managed to simultaneously become infused both with the dreams of the younger generations and the deep wisdom and self-awareness of a more mature person. He dreams of becoming an inspirational speaker someday, for kids in particular. Never mind that he was formerly sentenced to life in prison. On his first day of class, he shares his heart-wrenching story of hav- ing grown up with a single mother who was wracked with addiction for all of his young life. It’s a story that’s tragically not uncommon, and Quincy knows this. After he tells his story with an astonishing composure, and without blame or bitterness, he says, “But I know I’m not alone and there are so many kids out there who have the same stories. And I want to talk to them. I want to help them so they don’t end up here. Because there are a whole lot of other little ‘me’s’ out there.” So last month, we let Quincy prac- tice speaking for his inspirational cir- cuit gig dream on his inmate peers. -

THE University Suspends Mcaiarney

~-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Marjs VOLUME 40: ISSUE 69 WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 24,2007 NDSMCOBSERVER.COM University suspends McAiarney Tvvo tickets Irish point guard to miss spring, summer semesters following December possession charge face off in Brey thought he was dressing were as surprised as I am, they football team for a parietals vio By BOB GRIFFIN Kyle ... tonight for the St. John's were shocked." lation .. In early 2002, football SMC race News Writer game," Janice McAlarney said. Senior Associate Athletics players Lorenzo Crawford, "I have not spoken to Coach Director John Heisler told The Justin Smith, Donald Dykes and Notre Dame basketball player Brey [since the decision was Observer Tuesday he was Abram Elam were dismissed Davis-Kennedy first Kyle McAlarney was suspended made]. He's unable to comment. Notre Dame from the University following pair to be eliminated for the spring and summer 16 miles sports information director accusations of raping a female semesters Monday and is cur away from Bernie Cafarelli said she could Notre Dame student in an off rently on his way home to me right now not comment due to privacy campus house. Later in 2002, By KELLY MEEHAN Staten Island, N.Y., his mother with the laws. Irish running back Julius Jones Saint Mary's Editor said in a phone interview team, and Brey cannot comment on the was suspended for academic Tuesday afternoon with The he's where situation either, Cafarelli said. delinquency. The Annie Davis-Courtney Observer. he has to be. McAlarney, who was pulled Since McAlarney is suspended Kennedy ticket was the first elim Janice McAlarney said her son I don't blame over during a routine traffic for the spring and summer inated Tuesday from the three - a sophomore who was basketball in -..""""""""'-"-"" stop near campus early in the semesters, not dismissed - way race for the helm of Saint charged with possession of mar this at all. -

Family Album

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 Family Album Mary Elizabeth Bowen University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Bowen, Mary Elizabeth, "Family Album" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 909. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/909 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Family Album A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Mary Elizabeth (Missy) Bowen B.A., Grinnell College, 1981 May, 2009 © 2009, Mary Elizabeth (Missy) Bowen ii Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M. -

Outlandish Bionicle Stories

Outlandish Bionicle Stories by GaliGee of BZPower with gratitude and apologies to the creators of LEGO Bionicle, et al. ©2014 Barbies Invade Mata Nui ................................................................................................................ 2 Gali Loses Her Head..................................................................................................................... 21 Road Trip with Onua .................................................................................................................... 36 The Toa Nuva at Kennedy International Airport.......................................................................... 70 The Greening of Po-Koro, Featuring MakuTa ............................................................................. 85 Outlandish Bionicle Stories GaliGee Barbies Invade Mata Nui According to legend, the Barbies have invaded Mata Nui before (contact BZP historian Yotanua, Toa of Time, for details). Now they have returned, but this time their mission is different. This time they are on the hunt for eligible bachelors. Chapter 1: The Barbies Arrive Airline Pilot Barbie: OK, ladies, get your seatbelts securely fastened, and your tray tables in the upright and locked positions, and we'll be off to Mata Nui. Jewel Girl Teresa: Wait a minute. Is this a good idea? Are we just wasting more time? Those guys looked kind of weird on bionicle.com. And short, too. Coca Cola Picnic Barbie: Yeah, but what choice do we have? Obviously, there are no men back home. Midge: Ever since Sally made her only Ken marry Dream Date Barbie, there's no one left even to dream about. Fashion Party Teen Skipper: That [expletive deleted]. Snow Sisters Barbie: Now, now, Skipper. But I do wish Sally had a brother. [sighs] With some handsome boy toys. Sugar Plum Fairy Barbie: But Teresa may have a point. Should we even try this again? Maybe we should just be nuns. Malibu Barbie: Are you nuts? I know we've had bad luck so far. -

Pearl Harbor Lesson Plans. INSTITUTION Department of the Navy, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 478 862 SO 035 130 TITLE The Date That Lives in Infamy: Pearl Harbor Lesson Plans. INSTITUTION Department of the Navy, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2001-11-00 NOTE 75p.; Prepared by the Naval Historical Center. For additional history lessons about the U.S. Navy, see SO 035 131-136. AVAILABLE FROM Naval Historical Center, Washington Navy Yard, 805 Kidder Breese Street SE, Washington Navy Yard, DC 20374-5060. Tel: 202-433-4882; Fax: 202-433-8200. For full text: http://www.history.navy.mil/ . PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Curriculum Enrichment; High Schools; *Lesson Plans; Middle Schools; *Primary Sources; Social Studies; Student Research; *United States History; *World War II IDENTIFIERS Hawaii; *Pearl Harbor; Timelines ABSTRACT This lesson plan can help teachers and students understand what happened on Decirlber 7, 1941, beginning with the first U.S. treaty with Japan in 1854 through the attacks in 1941. Students use primary sources to synthesize information and draw conclusions about the role of the U.S. Navy in foreign policy and to understand how people in 1941 reacted to the bombing of Pearl Harbor (Hawaii). The lesson plan is designed for upper middle and high school students and consists of four sections: (1) "Permanent Friends: The Treaty of Kanagawa" (Treaty of Kanagawa; Teacher Information Sheet; Student Work Sheet; Fact Sheet: Commodore Matthew Perry);(2) "This Is Not a Drill" (Newspaper Publishing Teacher Information Sheet; A Moment in Time Photographs in Action (three)); and (Recalling Pearl Harbor: Oral Histories and Survivor Accounts (seven); Timeline and Action Reports (three)); (3) "The Aftermath" (Teacher Information Sheet; five Photographs; Action Report: USS Ward; Damage Reports: Ships; Fact Sheet Pearl Harbor); and (4)"A Date Which Will Live in Infamy" (President Franklin D. -

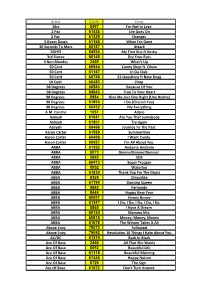

Karaoke List

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam