Wiz Kids, Nuclear Bombs, and Marvel's Hazmat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

X-Men Evolution Jumpchain V 1.0 by Multiversecrossover Welcome to a Earth-11052. Unlike Most of the Other Universes This Univers

X-Men Evolution Jumpchain V 1.0 By MultiverseCrossover Welcome to a Earth-11052. Unlike most of the other universes this universe focuses solely on the familiar X-Men with a twist. Most of the team is in school and just now are learning to control their powers. But don’t let the high school feel let you become complacent. Espionage, conspiracies, and hatred burn deep underneath the atmosphere and within a few months, the floodgates will open for the world to see. You begin on the day when a young Nightcrawler joins up with the X-Men along with a meddling toad thrown into the mix. You might wanna take this if you want to survive. +1000 Choice Points Origins All origins are free and along with getting the first 100 CP perk free of whatever your origin is you even get 50% off the rest of those perks in that same origin. Drop-In No explanation needed. You get dropped straight into your very own apartment located next to the Bayville High School if you so wish. Other than that you got no ties to anything so do whatever you want. Student You’re the fresh meat in this town and just recently enrolled here. You may or may not have seen a few of the more supernatural things in this high school but do make your years here a memorable one. Scholar Whether you’re a severely overqualified professor teaching or a teacher making new rounds at the local school one thing is for sure however. Not only do you have the smarts to back up what you teach but you can even make a change in people’s lives. -

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

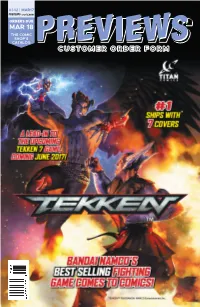

MAR17 World.Com PREVIEWS

#342 | MAR17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE MAR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Mar17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 1:36:31 PM Mar17 C2 DH - Buffy.indd 1 2/8/2017 4:27:55 PM REGRESSION #1 PREDATOR: IMAGE COMICS HUNTERS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUG! THE ADVENTURES OF FORAGER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT/ YOUNG ANIMAL JOE GOLEM: YOUNGBLOOD #1 OCCULT DETECTIVE— IMAGE COMICS THE OUTER DARK #1 DARK HORSE IDW’S FUNKO UNIVERSE MONTH EVENT IDW ENTERTAINMENT ALL-NEW GUARDIANS TITANS #11 OF THE GALAXY #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Mar17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 9:13:17 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Hero Cats: Midnight Over Steller City Volume 2 #1 G ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Stargate Universe: Back To Destiny #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Casper the Friendly Ghost #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Providence Act 2 Limited HC G AVATAR PRESS INC Victor LaValle’s Destroyer #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS Misfi t City #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Swordquest #0 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT James Bond: Service Special G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Spill Zone Volume 1 HC G :01 FIRST SECOND Catalyst Prime: Noble #1 G LION FORGE The Damned #1 G ONI PRESS INC. 1 Keyser Soze: Scorched Earth #1 G RED 5 COMICS Tekken #1 G TITAN COMICS Little Nightmares #1 G TITAN COMICS Disney Descendants Manga Volume 1 GN G TOKYOPOP Dragon Ball Super Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Line of Beauty: The Art of Wendy Pini HC G ART BOOKS Planet of the Apes: The Original Topps Trading Cards HC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES -

Fantastic Four Kree/Skrull Alliance Cotati Avengers

AVENGERS CAPTAIN CAPTAIN BLACK AMERICA IRON MAN MARVEL PANTHER THOR MANTIS WICCAN FANTASTIC FOUR MR. THE INVISIBLE THE HUMAN THE POWERHOUSE BRAINSTORM SPIDER-MAN WOLVERINE FANTASTIC WOMAN TORCH THING KREE/SKRULL ALLIANCE EMPEROR SUPER- CAPTAIN R’KLLL MUR-G’NN HULKLING SKRULL GLORY COTATI QUOI SWORDSMAN HULK After years of conflict, the Kree and Skrull Empires suddenly united under the leadership of Emperor Dorrek VIII, the Young Avenger and Kree/Skrull hybrid known as Hulkling. His first act as Emperor was to order their combined forces to Earth to defeat their mutual enemy, the plantlike race known as the Cotati. Led by Quoi, the prophesied Celestial Messiah, and his father, the Swordsman, the Cotati plan to eliminate all animal life --starting with Earth. The united members of the Avengers and Fantastic Four have been defending the planet from the invading Cotati but were unable to stop them from planting the seeds for the Death Blossom. Once it blooms, the Cotati will have control of all plant life in the galaxy. Captain Marvel and the Human Torch teamed up with former Young Avenger Wiccan, who revealed he and Hulkling had recently married. He also exposed Emperor Hulking as R’Klll, the former Skrull empress, in disguise. But while Wiccan and his allies freed the true Hulkling from captivity, they were too late to stop R’Klll from activating the Pyre, a weapon that will end the threat of the Cotati forever--by detonating Earth’s sun! story Al Ewing & Dan Slott script Al Ewing artist Valerio Schiti color artist Marte Gracia letterer VC’s Joe Caramagna cover Jim Cheung & Jay David Ramos variant covers Jim Cheung & Jay David Ramos; Michael Cho; John Tyler Christopher; Tony Daniel & Frank D’Armata; Alexander Lozano & Wade von Grawbadger; Mike McKone & Morry Hollowell; Mike Mignola graphic designer Carlos Lao assistant editor Martin Biro associate editor Alanna Smith editor Tom Brevoort editor in chief C.B. -

Comprehension Passages for Level 1-16

Comprehension Passages For Level 1-16 This resource contains the full text of reading comprehension passages in Levels 1 through 16 of Lexia® PowerUp Literacy®. It supports teachers in further scaffolding comprehension instruction and activities and enables students to interact with and annotate the text. The comprehension passages in PowerUp have been analysed using a number of tools to determine complexity, including Lexile® measures. Based on this analysis, the comprehension passages are appropriately complex for students reading at the year-level of skills in each program level. Texts with nonstandard punctuation, such as poems and plays, are not measured. The Content Area column in the table of contents can be used as a guide to determine the general topic of each passage. It does not indicate alignment to any specific content area standards. PR-C5-FP-G3-0121 Lexia® PowerUp Literacy® Comprehension Passages Activity Title Genre Content Area Lexile® Foundational: Level 1 The Trans-Alaska Pipeline Informational Social Studies 370L Activity 1 Camping and Fishing in Alaska Informational English Language Arts 470L Sliding Ice Informational Science 500L Activity 2 Speeding Glaciers Informational Science 430L Swimming Upstream Informational Science 540L Activity 3 Where the Buffalo Roam Informational Social Studies 580L A Hero Informational Social Studies 580L Activity 4 A Thinker Who Couldn’t Talk or Walk Informational Science 470L Foundational: Level 2 Exploring Beyond the Sea Informational Science 500L Activity 1 The Mighty Mississippi -

Chris Ware's Jimmy Corrigan

Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan : Honing the Hybridity of the Graphic Novel By DJ Dycus Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan : Honing the Hybridity of the Graphic Novel, by DJ Dycus This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by DJ Dycus All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3527-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3527-5 For my girls: T, A, O, and M TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................. ix CHAPTER ONE .............................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION TO COMICS The Fundamental Nature of this Thing Called Comics What’s in a Name? Broad Overview of Comics’ Historical Development Brief Survey of Recent Criticism Conclusion CHAPTER TWO ........................................................................................... 33 COMICS ’ PLACE WITHIN THE ARTISTIC LANDSCAPE Introduction Comics’ Relationship to Literature The Relationship of Comics to Film Comics’ Relationship to the Visual Arts Conclusion CHAPTER THREE ........................................................................................ 73 CHRIS WARE AND JIMMY CORRIGAN : AN INTRODUCTION Introduction Chris Ware’s Background and Beginnings in Comics Cartooning versus Drawing The Tone of Chris Ware’s Work Symbolism in Jimmy Corrigan Ware’s Use of Color Chris Ware’s Visual Design Chris Ware’s Use of the Past The Pacing of Ware’s Comics Conclusion viii Table of Contents CHAPTER FOUR ....................................................................................... -

The Pingry School Summer Reading 2017 Required Reading Entering Form II

The Pingry School Summer Reading 2017 Required Reading Entering Form II Please choose TWO of the following books to read this summer. For your first choice, you will complete the “Summer Reading Questionnaire” posted on the website; for your second choice, you will complete a creative project with your class in September. March Book 1, John Lewis Congressman John Lewis (GA-5) is an American icon, one of the key figures of the civil rights movement. His commitment to justice and nonviolence has taken him from an Alabama sharecropper’s farm to the halls of Congress, from a segregated schoolroom to the 1963 March on Washington, and from receiving beatings from state troopers to receiving the Medal of Freedom from the first African-American president. Now, to share his remarkable story with new generations, Lewis presents March, a graphic novel trilogy, in collaboration with co-writer Andrew Aydin and New York Times best-selling artist Nate Powell (winner of the Eisner Award and LA Times Book Prize finalist for Swallow Me Whole). March is a vivid first-hand account of John Lewis’ lifelong struggle for civil and human rights, meditating in the modern age on the distance traveled since the days of Jim Crow and segregation. Rooted in Lewis’ personal story, it also reflects on the highs and lows of the broader civil rights movement. Book One spans John Lewis’ youth in rural Alabama, his life-changing meeting with Martin Luther King, Jr., the birth of the Nashville Student Movement, and their battle to tear down segregation through nonviolent lunch counter sit-ins, building to a stunning climax on the steps of City Hall. -

By Gene Luen Yang & Mike Holmes

THE NATIONAL CHILDREN’S BOOK AND LITERACY ALLIANCE SECRET CODERS BY GENE LUEN YANG & MIKE HOLMES EDUCATION RESOURCE GUIDE: DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES Secret Coders is a graphic novel series by Gene Luen Yang and Mike Holmes that combines logic puzzles and basic programming instruction with a page-turning mystery plot. The series is recommended for readers in grades 3 through 8 and includes four books: • Secret Coders • Secret Coders: Paths & Portals • Secret Coders: Secrets & Sequences • Secret Coders: Robots & Repeats If you are uncertain whether the Secret Coders series is right for the young people in your life, take a moment to read “5 Reasons You Should Be Reading Secret Coders” by Graeme McMillan in WIRED. His five reasons are as follows: • You’ll Be Learning Coding from a Professional. • Secret Coders Might Be Educational, But It’s Not Boring. • Code: It’s Not Just for Computers Anymore. • Comics’ Hidden Superpower, Pedagogy! • You’ll Enjoy It—But It Might Change Your Kid’s Life. Read the entire article at this link: https://www.wired.com/2016/05/secret-coders-essentials/ The National Children’s Book and Literacy Alliance (thencbla.org) 1 Education Resource Guide for Author and Illustrator Gene Luen Yang DISCUSSION QUESTIONS Pose the following questions to young people: • Secret Coders opens with protagonist Hopper being dropped off at her new school, Stately Academy, for the first time. Hopper says she “downright dreaded transferring to Stately Academy.” Have you ever moved and needed to transfer to a new school? Did you dread the experience or were you excited about it? Even if you have never needed to change schools, write a list of what might worry you and what might excite you about making such a transition. -

Award Winning Books(Available at Klahowya SS Library) Michael Printz, Pulitzer Prize, National Book, Evergreen Book, Hugo, Edgar and Pen/Faulkner Awards

Award Winning Books(Available at Klahowya SS Library) Michael Printz, Pulitzer Prize, National Book, Evergreen Book, Hugo, Edgar and Pen/Faulkner Awards Updated 5/2014 Michael Printz Award Michael Printz Award continued… American Library Association award that recognizes best book written for teens based 2008 Honor book: Dreamquake: Book Two of the entirely on literary merit. Dreamhunter Duet by Elizabeth Knox 2014 2007 Midwinter Blood American Born Chinese (Graphic Novel) Call #: FIC SED Sedgwick, Marcus Call #: GN 741.5 YAN Yang, Gene Luen Honor Books: Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets Honor Books: of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Sáenz; Code Name The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to Verity by Elizabeth Wein; Dodger by Terry Pratchett the Nation; v. 1: The Pox Party, by M.T. Anderson; An Abundance of Katherines, by John Green; 2013 Surrender, by Sonya Hartnett; The Book Thief, by In Darkness Markus Zusak Call #: FIC LAD Lake, Nick 2006 Honor Book: The Scorpio Races, by Maggie Stiefvater Looking for Alaska : a novel Call #: FIC GRE Green, John 2012 Where Things Come Back: a novel Honor Book: I Am the Messenger , by Markus Zusak Call #: FIC WHA Whaley, John Corey 2011 2005 Ship Breaker How I Live Now Call #: FIC BAC Bacigalupi, Paolo Call #: FIC ROS Rosoff, Meg Honor Book: Stolen by Lucy Christopher Honor Books: Airborn, by Kenneth Oppel; Chanda’s 2010 Secrets, by Allan Stratton; Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy, by Gary D. Schmidt Going Bovine Call #: FIC BRA Bray, Libba 2004 The First Part Last Honor Books: The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Call #: FIC JOH Johnson, Angela Traitor to the Nation, Vol. -

This Session Will Be Begin Closing at 6PM on 5/19/20, So Be Sure to Get Those Bids in Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook & Twitter @Back2past for Updates

5/19 Bronze to Modern Comic Books, Board Games, & Toys 5/19/2021 This session will be begin closing at 6PM on 5/19/20, so be sure to get those bids in via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook & Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Policies 1 13 Uncanny X-Men #350/Gambit Holofoil Cover 1 Holofoil cover art by Joe Madureira. NM condition. 2 Amazing Spider-Man #606/Black Cat Cover 1 Cover art by J. Scott Campbell featuring The Black Cat. NM 14 The Mighty Avengers Near Run of (34) Comics 1 condition. First Secret Warriors. Lot includes issues #1-23, 25-33, and 35-36. NM condition. 3 Daredevil/Black Widow Figure Lot 1 Marvel Select. New in packages. Package have minor to moderate 15 Comic Book Superhero Trading Cards 1 shelf wear. Various series. Singles, promos, and chase cards. You get all pictured. 4 X-Men Origins One-Shot Lot of (4) 1 Gambit, Colossus, Emma Frost, and Sabretooth. NM condition. 16 Uncanny X-Men #283/Key 1st Bishop 1 First full appearance of Bishop, a time-traveling mutant who can 5 Guardians of The Galaxy #1-2/Key 1 New roster and origin of the Guardians of the Galaxy: Star-Lord, absorb and redistribute energy. NM condition. Gamora, Drax, Rocket Raccoon, Adam Warlock, Quasar and 17 Crimson Dawn #1-4 (X-Men) 1 Groot. -

Spider-Woman

DC MARVEL IMAGE ! ACTION ! ALIEN ! ASCENDER ! AMERICAN VAMPIRE 1976 ! AMAZING SPIDER-MAN ! BIRTHRIGHT ! AQUAMAN ! AVENGERS ! BITTER ROOT ! BATGIRL ! AVENGERS: MECH STRIKE 1-5 ! BLISS 1-8 ! BATMAN ! BETA RAY BILL 1-5 ! COMMANDERS IN CRISIS 1-12 ! BATMAN ADVENTURES CONTINUE ! BLACK CAT ! CROSSOVER ! BATMAN BLACK & WHITE 1-6 ! BLACK KNIGHT CURSE EBONY BLADE ! DEADLY CLASS ! BATMAN: URBAN LEGENDS ! BLACK WIDOW ! DECORUM ! BATMAN/CATWOMAN 1-12 ! CABLE ! DEEP BEYOND ! BATMAN/SUPERMAN ! CAPTAIN AMERICA ! DEPARTMENT OF TRUTH ! CATWOMAN ! CAPTAIN MARVEL ! EXCELLENCE ! CRIME SYNDICATE ! CARNAGE BW & BLOOD 1-4 ! FAMILY TREE ! DETECTIVE COMICS ! CHAMPIONS ! FIRE POWER ! DREAMING : WAKING HOURS ! CHILDREN OF THE ATOM ! GEIGER ! FAR SECTOR ! CONAN THE BARBARIAN ! ICE CREAM MAN ! FLASH ! DAREDEVIL ! JUPITERS LEGACY 1-5 ! GREEN ARROW ! DEADPOOL ! KARMEN 1-5 ! GREEN LANTERN ! DEMON DAYS X-MEN 1-5 ! KILLADELPHIA ! HARLEY QUINN ! ETERNALS ! LOW ! INFINITE FRONTIER ! EXCALIBUR ! MONSTRESS ! JOKER ! FANTASTIC 4 ! MOONSHINE ! JUSTICE LEAGUE ! FANTASTIC 4 LIFE STORY 1-6 ! NOCTERRA ! LAST GOD ! GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY ! OBLIVION SONG ! LEGENDS OF DARK KNIGHT ! HELLIONS ! OLD GUARD 1-6 ! LEGION of SUPER-HEROES ! HEROES REBORN 1-7 ! POST AMERICANA 1-6 ! MAN-BAT ! IMMORTAL HULK ! RADIANT BLACK ! NEXT BATMAN: SECOND SON ! IRON FIST Heart of Dragon 1-6 ! RAT QUEENS ! NIGHTWING ! IRON MAN ! REDNECK ! OTHER HISTORY DC UNIVERSE ! MAESTRO WAR & PAX 1-5 ! SAVAGE DRAGON ! RED HOOD ! MAGNIFICENT MS MARVEL ! SEA OF STARS ! RORSCHACH ! MARAUDERS ! SILVER COIN 1-5 ! SENSATIONAL