Introduction to the Lamu Archipelago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Registered Voters Per Constituency for 2017 General Elections

REGISTERED VOTERS PER CONSTITUENCY FOR 2017 GENERAL ELECTIONS COUNTY_ CONST_ NO. OF POLLING COUNTY_NAME CONSTITUENCY_NAME VOTERS CODE CODE STATIONS 001 MOMBASA 001 CHANGAMWE 86,331 136 001 MOMBASA 002 JOMVU 69,307 109 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 126,151 198 001 MOMBASA 004 NYALI 104,017 165 001 MOMBASA 005 LIKONI 87,326 140 001 MOMBASA 006 MVITA 107,091 186 002 KWALE 007 MSAMBWENI 68,621 129 002 KWALE 008 LUNGALUNGA 56,948 118 002 KWALE 009 MATUGA 70,366 153 002 KWALE 010 KINANGO 85,106 212 003 KILIFI 011 KILIFI NORTH 101,978 182 003 KILIFI 012 KILIFI SOUTH 84,865 147 003 KILIFI 013 KALOLENI 60,470 123 003 KILIFI 014 RABAI 50,332 93 003 KILIFI 015 GANZE 54,760 132 003 KILIFI 016 MALINDI 87,210 154 003 KILIFI 017 MAGARINI 68,453 157 004 TANA RIVER 018 GARSEN 46,819 113 004 TANA RIVER 019 GALOLE 33,356 93 004 TANA RIVER 020 BURA 38,152 101 005 LAMU 021 LAMU EAST 18,234 45 005 LAMU 022 LAMU WEST 51,542 122 006 TAITA TAVETA 023 TAVETA 34,302 79 006 TAITA TAVETA 024 WUNDANYI 29,911 69 006 TAITA TAVETA 025 MWATATE 39,031 96 006 TAITA TAVETA 026 VOI 52,472 110 007 GARISSA 027 GARISSA TOWNSHIP 54,291 97 007 GARISSA 028 BALAMBALA 20,145 53 007 GARISSA 029 LAGDERA 20,547 46 007 GARISSA 030 DADAAB 25,762 56 007 GARISSA 031 FAFI 19,883 61 007 GARISSA 032 IJARA 22,722 68 008 WAJIR 033 WAJIR NORTH 24,550 76 008 WAJIR 034 WAJIR EAST 26,964 65 008 WAJIR 035 TARBAJ 19,699 50 008 WAJIR 036 WAJIR WEST 27,544 75 008 WAJIR 037 ELDAS 18,676 49 008 WAJIR 038 WAJIR SOUTH 45,469 119 009 MANDERA 039 MANDERA WEST 26,816 58 009 MANDERA 040 BANISSA 18,476 53 009 MANDERA -

Tracker June/July 2014

KENYA MUSEUM SOCIETY Tracker June/July 2014 Joy Adamson Exhibition Photo by Ebrahim Mwangi, NMK AV Dept Kenya Museum Society P.O. Box 40658 - 00100 Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] www.kenyamuseumsociety.org Tel: 3743808/2339158 (Direct) kenyamuseumsociety Tel: 8164134/5/6 ext 2311 Cell: 0724255299 @museumsociety DRY ASSOCIATES LTD Investment Group Offering you a rainbow of opportunities ... Wealth Management Since 1994 Dry Associates House Brookside Grove, Westlands, Nairobi Tel: +254 (20) 445-0520/1 +254 (20) 234-9651 Mobile(s): 0705799971/0705849429/ 0738253811 June/July 2014 Tracker www.dryassociates.com2 NEWS FROM NMK Joy Adamson Exhibition New at Nairobi National Museum he historic collections of Joy Adamson’s portraits of the peoples of Kenya as well as her botanical and wildlife paintings are once again on view at the TNairobi National Museum. This exhibi- tion includes 50 of Joy’s intriguing portraits and her beautiful botanicals and wildlifeThe exhibition,illustrations funded that are by complementedKMS was officially by related opened objects on May from 19. the muse- um’sVisit ethnographic the KMS shop and where scientific cards collections. featuring some of the portraits are available as is the book, Peoples of Kenya; KMS members are entitled to a 5 per cent dis- count on books. The museum is open seven days a week from 9.30 am to 5.30 pm. Joy Adamson Exhibition Photo by Ebrahim Mwangi, NMK AV Dept June/July 2014 Tracker 3 KMS EASTER SAFARI 18Tsavo - 21 APRIL West 2014 National Park By James Reynolds he Kenya Museum Society's Easter trip saw organiser Narinder Heyer Ta simple but tasty snack in Makindu's Sikh temple, the group entered lead a group of 21 people in 7 vehicles to Tsavo West National Park. -

Guide to Daily Correspondence of the Coast, Rift Valley, Central, and Northeastern Provinces : Kenya National Archives Microfilm

Syracuse University SURFACE Kenya National Archives Guides Library Digitized Collections 1984 Guide to daily correspondence of the Coast, Rift Valley, Central, and Northeastern Provinces : Kenya National Archives microfilm Robert G. Gregory Syracuse University Richard E. Lewis Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/archiveguidekenya Part of the African Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gregory, Robert G. and Lewis, Richard E., "Guide to daily correspondence of the Coast, Rift Valley, Central, and Northeastern Provinces : Kenya National Archives microfilm" (1984). Kenya National Archives Guides. 8. https://surface.syr.edu/archiveguidekenya/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Digitized Collections at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kenya National Archives Guides by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Microfilm 4752 111111.111132911 02626671 8 MEPJA A Guide INC£)( to Daily Correspondence 1n~ of the ..:S 9 Coast, Rift Valley, Central;o.~ and Northeastern Provinces: KENYA NATIONAL ARCHIVES MICROFILM Robert G. Gregory and Richard E. Lewis Eastern Africa Occasional Bibliography No. 28 Foreign and Comparative Studies Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs Syracuse University 1984 Copyright 1984 by MAXWELL SCHOOL OF CITIZENSHIP AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY, SYRACUSE, NEW YORK, U.S.A. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Gregory, Robert G. A guide to daily correspondence of the Coast, Rift Valley, Central, and Northeastern Provinces. (Eastern Africa occasional bibliography; no. 28) 1. Kenya National Archives--Microform catalogs. 2. Kenya--Politics and government--Sources--Bibliography- Microform catalogs. 3. Kenya--History--Sources--Bibliogra phy--Microform catalogs. -

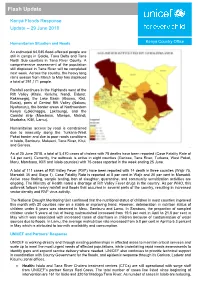

Flash Update

Flash Update Kenya Floods Response Update – 29 June 2018 Humanitarian Situation and Needs Kenya Country Office An estimated 64,045 flood-affected people are still in camps in Galole, Tana Delta and Tana North Sub counties in Tana River County. A comprehensive assessment of the population still displaced in Tana River will be completed next week. Across the country, the heavy long rains season from March to May has displaced a total of 291,171 people. Rainfall continues in the Highlands west of the Rift Valley (Kitale, Kericho, Nandi, Eldoret, Kakamega), the Lake Basin (Kisumu, Kisii, Busia), parts of Central Rift Valley (Nakuru, Nyahururu), the border areas of Northwestern Kenya (Lokichoggio, Lokitaung), and the Coastal strip (Mombasa, Mtwapa, Malindi, Msabaha, Kilifi, Lamu). Humanitarian access by road is constrained due to insecurity along the Turkana-West Pokot border and due to poor roads conditions in Isiolo, Samburu, Makueni, Tana River, Kitui, and Garissa. As of 25 June 2018, a total of 5,470 cases of cholera with 78 deaths have been reported (Case Fatality Rate of 1.4 per cent). Currently, the outbreak is active in eight counties (Garissa, Tana River, Turkana, West Pokot, Meru, Mombasa, Kilifi and Isiolo counties) with 75 cases reported in the week ending 25 June. A total of 111 cases of Rift Valley Fever (RVF) have been reported with 14 death in three counties (Wajir 75, Marsabit 35 and Siaya 1). Case Fatality Rate is reported at 8 per cent in Wajir and 20 per cent in Marsabit. Active case finding, sample testing, ban of slaughter, quarantine, and community sensitization activities are ongoing. -

Kenya.Pdf 43

Table of Contents PROFILE ..............................................................................................................6 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Facts and Figures.......................................................................................................................................... 6 International Disputes: .............................................................................................................................. 11 Trafficking in Persons:............................................................................................................................... 11 Illicit Drugs: ................................................................................................................................................ 11 GEOGRAPHY.....................................................................................................12 Kenya’s Neighborhood............................................................................................................................... 12 Somalia ........................................................................................................................................................ 12 Ethiopia ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 Sudan.......................................................................................................................................................... -

National Drought Early Warning Bulletin June 2021

NATIONAL DROUGHT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY National Drought Early Warning Bulletin June 2021 1 Drought indicators Rainfall Performance The month of May 2021 marks the cessation of the Long- Rains over most parts of the country except for the western and Coastal regions according to Kenya Metrological Department. During the month of May 2021, most ASAL counties received over 70 percent of average rainfall except Wajir, Garissa, Kilifi, Lamu, Kwale, Taita Taveta and Tana River that received between 25-50 percent of average amounts of rainfall during the month of May as shown in Figure 1. Spatio-temporal rainfall distribution was generally uneven and poor across the ASAL counties. Figure 1 indicates rainfall performance during the month of May as Figure 1.May Rainfall Performance percentage of long term mean(LTM). Rainfall Forecast According to Kenya Metrological Department (KMD), several parts of the country will be generally dry and sunny during the month of June 2021. Counties in Northwestern Region including Turkana, West Pokot and Samburu are likely to be sunny and dry with occasional rainfall expected from the third week of the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be near the long-term average amounts for June. Counties in the Coastal strip including Tana River, Kilifi, Lamu and Kwale will likely receive occasional rainfall that is expected throughout the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be below the long-term average amounts for June. The Highlands East of the Rift Valley counties including Nyeri, Meru, Embu and Tharaka Nithi are expected to experience occasional cool and cloudy Figure 2.Rainfall forecast (overcast skies) conditions with occasional light morning rains/drizzles. -

Marine Habitats of the Lamu-Kiunga Coast: an Assessment of Biodiversity Value, Threats and Opportunities

Marine habitats of the Lamu-Kiunga coast: an assessment of biodiversity value, threats and opportunities Kennedy Osuka, Melita Samoilys, James Mbugua, Jan de Leeuw, David Obura Marine habitats of the Lamu-Kiunga coast: an assessment of biodiversity value, threats and opportunities Kennedy Osuka, Melita Samoilys, James Mbugua, Jan de Leeuw, David Obura LIMITED CIRCULATION Correct citation: Osuka K, Melita Samoilys M, Mbugua J, de Leeuw J, Obura D. 2016. Marine habitats of the Lamu-Kiunga coast: an assessment of biodiversity value, threats and opportunities. ICRAF Working paper number no. 248 World Agroforestry Centre. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5716/WP16167.PDF Titles in the Working Paper series aim to disseminate interim results on agroforestry research and practices, and stimulate feedback from the scientific community. Other publication series from the World Agroforestry Centre include: Technical Manuals, Occasional Papers and the Trees for Change Series. Published by the World Agroforestry Centre United Nations Avenue PO Box 30677, GPO 00100 Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 7224000, via USA +1 650 833 6645 Email: [email protected] Website: www.worlagroforestry.org © World Agroforestry Centre 2016 Working Paper No. 248 Photos/illustrations: all photos are appropriately accredited. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the World Agroforestry Centre. Articles appearing in this publication may be quoted or reproduced without charge, provided the source is acknowledged. All images remain the sole property of their source and may not be used for any purpose without written permission from the source. i About the authors Kennedy Osuka is research scientist at CORDIO East Africa. -

The Lamu House - an East African Architectural Enigma Gerald Steyn

The Lamu house - an East African architectural enigma Gerald Steyn Department of Architecture of Technikon Pretoria. E-mail: [email protected]. Lamu is a living town off the Kenya coast. It was recently nominated to the World Heritage List. The town has been relatively undisturbed by colonization and modernization. This study reports on the early Swahili dwelling, which is still a functioning type in Lamu. It commences with a brief historical perspective of Lamu in its Swahili and East African coastal setting. It compares descriptions of the Lamu house, as found in literature, with personal observations and field surveys, including a short description of construction methods. The study offers observations on conservation and the current state of the Lamu house. It is concluded with a comparison between Lamu and Stone Town, Zanzibar, in terms of house types and settlement patterns. We found that the Lamu house is the stage for Swahili ritual and that the ancient and climatically uncomfortable plan form has been retained for nearly a millennium because of its symbolic value. Introduction The Swahili Coast of East Africa was recentl y referred to as " ... this important, but relatively little-knqwn corner of the 1 western Indian Ocean" • It has been suggested that the Lamu Archipelago is the cradle of the Swahili 2 civilization . Not everybody agrees, but Lamu Town is nevertheless a very recent addition to the World Heritage Lise. This nomination will undoubtedly attract more tourism and more academic attention. Figure 1. Lamu retains its 19th century character. What makes Lamu attractive to discerning tourists? Most certainly the natural beauty and the laid back style. -

Swahili Culture Reconsidered: Some Historical Implications of the Material Culture of the Northern Kenya Coast in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Swahili culture reconsidered: some historical implications of the material culture of the Northern Kenya Coast in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.sip200024 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Swahili culture reconsidered: some historical implications of the material culture of the Northern Kenya Coast in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Author/Creator Allen, James de Vere Date 1974 Resource type Articles Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Northern Swahili Coast, Tanzania, United Republic of, Kilwa Kisiwani Source Smithsonian Institution Libraries, DT365 .A992 Relation Azania: Journal of the British Insitute of History and Archaeology in East Africa, Vol. -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Kenya Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman ©2010 Feinstein International Center

A PR I L 2 0 1 0 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Kenya Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman ©2010 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu Acknowledgements The report has been written by Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman, who take responsibility for its contents and conclusions. We wish to thank our co-researchers Halima Shuria, Hussein A. Mahmoud, and Amina Soud for their substantive contribution to the research process. Andrew Catley, Lynn Carter, and Jan Bachmann provided insightful comments on a draft of the report. Dawn Stallard’s editorial skills made the report more readable. For reasons of confidentiality, the names of some individuals interviewed during the course of the research have been withheld. We wish to acknowledge and thank all of those who gave their time to be interviewed for the study. -

Cultural Identity: Kenya and the Coast by HANNAH WADDILOVE

RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE MEETING REPORT JANUARY 2017 Cultural Identity: Kenya and the coast BY HANNAH WADDILOVE Lamu Island on Kenya’s coast. Panellists Key points Mahmoud Ahmed Abdulkadir (Historian) • Lack of popular knowledge on the coast’s long history impedes understanding of Stanbuli Abdullahi Nassir (Civil Society/Human contemporary grievances. Rights Activist) • Claims to coastal sovereignty have been used politically but fall prey to divisions among Moderator coastal communities. Billy Kahora (Kwani Trust) • Struggles to define coastal cultural identity damage the drive to demand political and Introduction economic rights. During 2010 and 2011, a secessionist campaign led • Concerns about economic marginalization are by a group calling itself the Mombasa Republican acute for mega-infrastructure projects. Council (MRC) dominated debates about coastal politics. As a result of local grievances, the MRC’s • The failure of coastal representatives has contributed to the region’s marginal political call for secession attracted a degree of public status on the national stage. sympathy on the coast. Debates emerged that portrayed two contrasting agreement with the British colonialists to govern images of Kenya: the inclusive nation which the Ten-Mile strip in return for rents. In most embraces the coast, and a distinctive up-country interpretations, the British assurance to protect world which is culturally and politically remote the property and land rights of the Sultan’s from the coast. subject people meant only those of Arab descent. For Stanbuli, it was the root of contemporary On 7 December 2016, the Rift Valley Forum and injustices over racial hierarchies and land rights at Kwani Trust hosted a public forum in Mombasa to the coast, at the continued expense of indigenous discuss the place of the Kenyan coast in Kenya’s communities.