CNN and Citizen Journalism in Network Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liechtensteinisches Landesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2013 Nr

946.223.3 Liechtensteinisches Landesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2013 Nr. 143 ausgegeben am 25. März 2013 Verordnung vom 20. März 2013 betreffend die Abänderung der Verordnung über Massnahmen gegenüber der Islamischen Republik Iran Aufgrund von Art. 2 des Gesetzes vom 10. Dezember 2008 über die Durchsetzung internationaler Sanktionen (ISG), LGBl. 2009 Nr. 41, unter Einbezug der aufgrund des Zollvertrages anwendbaren schweizeri- schen Rechtsvorschriften und der Beschlüsse des Rates der Europäischen Union vom 26. Juli 2010 (2010/413/GASP), vom 12. April 2011 (2011/235/GASP), vom 23. Mai 2011 (2011/299/GASP), vom 10. Oktober 2011 (2011/670/GASP), vom 1. Dezember 2011 (2011/783/GASP), vom 23. Januar 2012 (2012/35/GASP), vom 15. März 2012 (2012/152/GASP), vom 23. März 2012 (2012/168/GASP), vom 23. April 2012 (2012/205/GASP), vom 2. August 2012 (2012/457/GASP), vom 15. Oktober 2012 (2012/635/GASP), vom 21. Dezember 2012 (2012/829/GASP) und vom 11. März 2013 (2013/124/GASP) sowie in Ausführung der Resolutionen 1737 (2006) vom 23. Dezember 2006, 1747 (2007) vom 24. März 2007, 1803 (2008) vom 3. März 2008 und 1929 (2010) vom 9. Juni 2010 des Si- cherheitsrates der Vereinten Nationen verordnet die Regierung: I. Abänderung bisherigen Rechts Die Verordnung vom 1. Februar 2011 über Massnahmen gegenüber der Islamischen Republik Iran, LGBl. 2011 Nr. 55, in der geltenden Fas- sung, wird wie folgt abgeändert: 2 Anhang 6 Bst. A Überschrift vor Ziff. 1, Überschrift nach Ziff. 326 sowie Ziff. 1 A. Unternehmen und Organisationen a) Beschluss 2010/413/GASP … b) Beschluss 2011/235/GASP Name Identifizierungsinformation 1. -

6. from Amateur Video to New Documentary Formats : Citizen

6. From Amateur Video to New Documentary Formats : Citizen Journalism and a Reconfiguring of Historical Knowledge Katarzyna Ruchel-Stockmans Abstract The Arab Spring of 2011 appeared on the news in countless video testimoni- als shot by participants and bystanders. Yet the sheer amount of such visual data, combined with the untranslatability and poor quality of the footage, delivers an often opaque and ambiguous material. Peter Snowdon’s film The Uprising (2013) appropriates and reassembles this amateur footage. Compared to the 1992 film Videograms of a Revolution by Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujică, The Uprising raises the question of a possible knowledge shift produced and performed by the amateur video maker. In an analysis of these films, this chapter investigates the possibilities of documenting historical events through mobile video footage. Keywords: Documentary, found footage film, Syria, amateur The act of self-immolation by the fruit vendor Mohamed Bouazizi in December 2010 triggered a wave of demonstrations throughout Tunisia, mobilizing masses of people to oppose the failing government. The spirit of protest quickly spread to other countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Spontaneous demonstrations emerged and expanded not only in the streets but also through an unprecedented use of social media. As a result, virtually anyone in the world could instantly see the events by means of images and mostly mobile phone camera videos, recorded and uploaded to the internet on a massive scale from various epicentres of the protests. Many citizens turned into amateur journalists in protesting against Strohmaier, A. and A. Krewani (eds.), Media and Mapping Practices in the Middle East and North Africa: Producing Space. -

CITIZEN JOURNALISM and the INTERNET by Nadine Jurrat April 2011

REFERENCE SERIES NO. 4 MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: CITIZEN JOURNALISM AND THE INTERNET By Nadine Jurrat April 2011 Citizen Journalism and the Internet —An Overview WRITTEN BY Nadine Jurrat1 Citizen journalists have become regular contributors to mainstream news, providing information and some of today’s most iconic images, especially where professional journalists have limited access or none at all. While some hail this opportunity to improve journalism, others fear that too much importance is placed on these personal accounts, undermining ethical standards and, eventually, professional journalism. Th is paper summarizes recent discussions about citizen journalism: its various forms and coming of age; its role in international news; the opportunities for a more democratic practice of journalism; the signifi cance for mass media outlets as they struggle for survival; the risks that unedited citizens’ contributions may pose for audiences, mainstream media, and citizen journalists themselves. Th e paper ends with a call for a clearer defi nition of ‘citizen journalism’ and for further ethical, legal and business training, so that its practitioners continue to be taken seriously by professional media and audiences alike. 1. Nadine Jurrat is an independent media researcher. Mapping Digital Media Th e values that underpin good journalism, the need of citizens for reliable and abundant information, and the importance of such information for a healthy society and a robust democracy: these are perennial, and provide compass-bearings for anyone trying to make sense of current changes across the media landscape. Th e standards in the profession are in the process of being set. Most of the eff ects on journalism imposed by new technology are shaped in the most developed societies, but these changes are equally infl uencing the media in less developed societies. -

Asia 21 Press Release FINAL3

News Public Relations Department 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021-5088 www.AsiaSociety.org Phone 212.327.9271 Fax 212.517.8315 E-mail [email protected] ASIA SOCIETY ANNOUNCES 2010-2011 FELLOWS CLASS OF ASIA 21 YOUNG LEADERS 19 Fellows selected representing 16 countries New York, January 27, 2010 – The Asia Society today announced the names of its 2010-2011 Class of Asia Society Asia 21 Fellows, a total of 19 next generation leaders from 16 countries in the Asia Pacific region. The Asia 21 Young Leaders Initiative, established by the Asia Society with support from Founding International Sponsor Bank of America Merrill Lynch, is the pre- eminent leadership development program in the Asia-Pacific region for emerging leaders under the age of 40. Representing a broad range of sectors, the Fellows will come together three times during their Fellowship year to address topics relating to environmental degradation, economic development, poverty eradication, universal education, conflict resolution, HIV/AIDS and public health crises, human rights, and other issues. They will meet twice at the Asia 21 Young Leaders Forum, and once at the Asia 21 Young Leaders Summit, set to be held in late 2010. The first meeting of the 2010-2011 Class will be held in Florida from February 28 to March 3, 2010 where they will participate in a series of meetings designed to generate creative, shared approaches to leadership and problem solving and develop collaborative public service projects. The Class includes an Iranian journalist and filmmaker whose detention after last year’s Iranian elections led to a major international campaign for his release, one of the leading environmental lawyers in China, and an astronaut trainer. -

Nuclear Fatwa Religion and Politics in Iran’S Proliferation Strategy

Nuclear Fatwa Religion and Politics in Iran’s Proliferation Strategy Michael Eisenstadt and Mehdi Khalaji Policy Focus #115 | September 2011 Nuclear Fatwa Religion and Politics in Iran’s Proliferation Strategy Michael Eisenstadt and Mehdi Khalaji Policy Focus #115 | September 2011 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2011 by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2011 in the United States of America by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei delivering a speech on November 8, 2006, where he stated that his country would continue to acquire nuclear technology and challenge “Western fabrications.” (AP Photo/ISNA, Morteza Farajabadi) Contents About the Authors. v Preface. vii Executive Sumary . ix 1. Religious Ideologies, Political Doctrines, and Nuclear Decisionmaking . 1 Michael Eisenstadt 2. Shiite Jurisprudence, Political Expediency, and Nuclear Weapons. 13 Mehdi Khalaji About the Authors Michael Eisenstadt is director of the Military and Security Studies Program at The Washington Institute. A spe- cialist in Persian Gulf and Arab-Israeli security affairs, he has published widely -

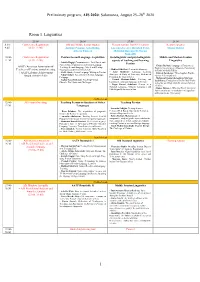

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Incitement: Antisemitism and Violence in Iran’S Current State Textbooks

A report from ADL International Affairs FEB 2021 Incitement: Antisemitism and Violence in Iran’s Current State Textbooks (top) Image titled “Let’s Go” from a current Iranian state textbook depicting an IRGC officer killed in Syria named Mohsen Hojaji. Grade 10, Defense Preparation, page 123 (bottom) Image from a current Iranian state textbook, in a lesson titled “Cultural Attack”. Grade 9, Heaven’s Messages: Islamic Education and Training, p. 105 Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment to all. ADL INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS ADL’s International Affairs (IA) pursues ADL’s mission around the globe, fighting antisemitism and hate, supporting the security of Jewish communities worldwide and working for a safe, democratic and pluralistic State of Israel at peace with her neighbors. ADL places a special emphasis on Europe, Latin America and Israel, but advocates for many Jewish communities around the world facing antisemitism. With a full-time staff in Israel, IA promotes social cohesion in Israel as a means of strengthening the Jewish and democratic character of the State, while opposing efforts to delegitimize it. The IA staff helps raise these international issues with the U.S. and foreign ABOUT THE AUTHOR governments and works with partners around the world to provide research and David Andrew Weinberg is analysis, programs and resources to fight antisemitism, extremism, hate crimes ADL’s Washington Director for and cyberhate. With a seasoned staff of international affairs experts, ADL’s IA International Affairs. He also division is one of the world’s foremost authorities in combatting all forms of serves as the organization’s hate globally. -

Council Decision (Cfsp) 2021/595

L 125/58 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union 13.4.2021 COUNCIL DECISION (CFSP) 2021/595 of 12 April 2021 amending Decision 2011/235/CFSP concerning restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities in view of the situation in Iran THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in particular Article 29 thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Whereas: (1) On 12 April 2011, the Council adopted Decision 2011/235/CFSP (1). (2) On the basis of a review of Decision 2011/235/CFSP, the Council considers that the restrictive measures set out therein should be renewed until 13 April 2022. (3) One person designated in the Annex to Decision 2011/235/CFSP is deceased, and his entry should be removed from that Annex. The Council has also concluded that the entries concerning 34 persons and one entity included in the Annex to Decision 2011/235/CFSP should be updated. (4) Decision 2011/235/CFSP should therefore be amended accordingly, HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION: Article 1 Decision 2011/235/CFSP is amended as follows: (1) in Article 6, paragraph 2 is replaced by the following: ‘2. This Decision shall apply until 13 April 2022. It shall be kept under constant review. It shall be renewed, or amended as appropriate, if the Council deems that its objectives have not been met.’; (2) the Annex is amended as set out in the Annex to this Decision. Article 2 This Decision shall enter into force on the date of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union. -

MDE 130622010 from Protest to Prison WITHOUT PICTURE

FROM PROTEST TO PRISON IRAN ONE YEAR AFTER THE ELECTION Amnesty International Publications First published in 2010 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2008 Index: MDE 13/062/2010 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................5 2. Who are the prisoners? ..............................................................................................9 Political activists .....................................................................................................10 -

Audience Report on CNN

Audience Report on CNN Ali Hashmi Shaina Humphries Maureen LaForge Jean Song Winter, 2012: Audience Insight F 1 | Page Introduction Founded in 1980 by Ted Turner, Cable News Network was the first 24-hour television news channel in the world. Some called it the “Chicken Noodle Network” because they lost revenue at a rate of 2 million dollars a month in their first year. CNN was even denied access to the White House pool in the early 1980s. However, they grew to be one of the largest news organizations, reaching 100 million households in U.S. and 265 million households abroad1. “He who laughs last, laughs best. They’re not laughing anymore,” Turner said in an interview with Michael Rosen in 1999. “I’m doing the laughing now.”2 CNN’S PERSONA Based on our own data and research, as well as that of the Pew Research Center and the Project for Excellence in Journalism, we have identified the persona of CNN’s audience. This person is a college-educated woman3 between the ages of 25 and 54, who tends to lean to the political left—but prefers her news to be neutral, and who cares mostly about national news as opposed to international and local news. She is on-the-go and does not have a lot of spare time to just sit around and watch the news on TV or read a newspaper. She receives most of her news online or through her smartphone, but often watches cable television news for quick, short periods of time. 1 CNN Worldwide Fact Sheet.” Web. -

Exploring the Role of Smartphone Technology for Citizen Science in Agriculture Katharina Dehnen-Schmutz, Gemma L

Exploring the role of smartphone technology for citizen science in agriculture Katharina Dehnen-Schmutz, Gemma L. Foster, Luke Owen, Séverine Persello To cite this version: Katharina Dehnen-Schmutz, Gemma L. Foster, Luke Owen, Séverine Persello. Exploring the role of smartphone technology for citizen science in agriculture. Agronomy for Sustainable Develop- ment, Springer Verlag/EDP Sciences/INRA, 2016, 36 (2), pp.25. 10.1007/s13593-016-0359-9. hal- 01532449 HAL Id: hal-01532449 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01532449 Submitted on 2 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Agron. Sustain. Dev. (2016) 36: 25 DOI 10.1007/s13593-016-0359-9 RESEARCH ARTICLE Exploring the role of smartphone technology for citizen science in agriculture Katharina Dehnen-Schmutz1 & Gemma L. Foster1 & Luke Owen1 & Séverine Persello2,3 Accepted: 16 March 2016 /Published online: 8 April 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Citizen science is the involvement of citizens, such support was not always regarded as necessary, experimental as farmers, in the research process. Citizen science has be- work was the most likely activity for which respondents come increasingly popular recently, supported by the prolifer- thought financial support would be essential. -

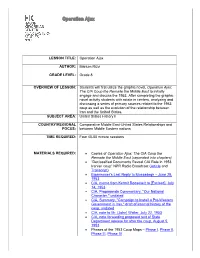

Operation Ajax

Operation Ajax LESSON TITLE: Operation Ajax AUTHOR: Marium Rizvi GRADE LEVEL: Grade 8 OVERVIEW OF LESSON: Students will first utilize the graphic novel, Operation Ajax: The CIA Coup the Remade the Middle East to initially engage and discuss the 1953. After completing the graphic novel activity students with rotate in centers, analyzing and discussing a series of primary sources related to the 1953 coup as well as the evolution of the relationship between Iran and the United States. SUBJECT AREA: United States History II COUNTRY/REGIONAL Comparative Middle East-United States Relationships and FOCUS: between Middle Eastern nations TIME REQUIRED: Four 45-55 minute sessions MATERIALS REQUIRED: • Copies of Operation Ajax: The CIA Coup the Remade the Middle East (separated into chapters) • “Declassified Documents Reveal CIA Role in 1953 Iranian coup” NPR Radio Broadcast (Article and Transcript) • Eisenhower’s Last Reply to Mossadegh – June 29, 1953 • CIA, memo from Kermit Roosevelt to [Excised], July 14, 1953 • CIA, Propaganda Commentary, "Our National Character," undated • CIA, Summary, "Campaign to Install a Pro-Western Government in Iran," draft of internal history of the coup, undated • CIA, note to Mr. [John] Waller, July 22, 1953 • CIA, note forwarding proposed text of State Department release for after the coup, August 5, 1953 • Phases of the 1953 Coup Maps – Phase I, Phase II, Phase III, Phase IV Operation Ajax • Iranian Parliament Passes Bill To Sue Washington Over 1953 Coup • Iran seeks money from U.S. over 1953 coup that empowered American-backed shah • Can Iran sue the US for Coup & supporting Saddam in Iran-Iraq War? • Iran MPs want US to pay for damage inflicted since 1953 (PressTV clip) • CIA, Memo, "Proposed Commendation for Communications Personnel who have serviced the TPAJAX Operation," Frank G.