Antique and Renaissance Models in the King Sigismund Chapel in Cracow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Etude Des Sources De Carbone Et D'énergie Pour La Synthèse Des Lipides De Stockage Chez La Microalgue Verte Modèle Chlamydo

Aix Marseille Université L'Ecole Doctorale 62 « Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé » Etude des sources de carbone et d’énergie pour la synthèse des lipides de stockage chez la microalgue verte modèle Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Yuanxue LIANG Soutenue publiquement le 17 janvier 2019 pour obtenir le grade de « Docteur en biologie » Jury Professor Claire REMACLE, Université de Liège (Rapporteuse) Dr. David DAUVILLEE, CNRS Lille (Rapporteur) Professor Stefano CAFFARRI, Aix Marseille Université (Examinateur) Dr. Gilles PELTIER, CEA Cadarache (Invité) Dr. Yonghua LI-BEISSON, CEA Cadarache (Directeur de thèse) 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Dr. Yonghua Li-Beisson for the continuous support during my PhD study and also gave me much help in daily life, for her patience, motivation and immense knowledge. I could not have imagined having a better mentor. I’m also thankful for the opportunity she gave me to conduct my PhD research in an excellent laboratory and in the HelioBiotec platform. I would also like to thank another three important scientists: Dr. Gilles Peltier (co- supervisor), Dr. Fred Beisson and Dr. Pierre Richaud who helped me in various aspects of the project. I’m not only thankful for their insightful comments, suggestion, help and encouragement, but also for the hard question which incented me to widen my research from various perspectives. I would also like to thank collaboration from Fantao, Emmannuelle, Yariv, Saleh, and Alisdair. Fantao taught me how to cultivate and work with Chlamydomonas. Emmannuelle performed bioinformatic analyses. Yariv, Saleh and Alisdair from Potsdam for amino acid analysis. -

3-2-18 Legals

FICTITIOUS BUSINESS NAME STATEMENT NO. 2018-9001115 Hazel Blue & Com- pany located at 8215 FICTITIOUS Phyllis Pl., San Diego, BUSINESS NAME CA 92123. Registrant: STATEMENT NO. Heather lee Running- FICTITIOUS 2018-9002374 wolf Harrison, 8215 BUSINESS NAME FICTITIOUS Quickwash National FICTITIOUS Phyllis Pl., San Diego, STATEMENT NO. BUSINESS NAME City located at 2415 E. BUSINESS NAME CA 92123; Kelley Di- 2018-9002669 STATEMENT NO. 18th St., National City, STATEMENT NO. ane Ross, 6434 49th Memorable Creations 2018-9003209 CA 91950. Registrant: FICTITIOUS 2018-9003456 St., San Diego, CA by Nita located at 571 Mind Over Matter Quickwash Holdings BUSINESS NAME Adventure Booked 92120. This business is Island Breeze Ln., San Marketing Inc located LLC, 1127 E. 30th St., STATEMENT NO. located at 1312 Indian conducted by: General Diego, CA 92154. Re- at 1631 Copper Penny N a t i o n a l C i t y , C A 2018-9003493 Creek Pl., Chula Vista, Partnership. The first gistrant: Renita Mar- Dr., Chula Vista, CA 91950. This business is Premier Trucking loc- CA 91915. Registrant: day of business was: garet Stewart, 571 Is- 91915. Registrant: conducted by: Limited FICTITIOUS ated at 205 Quintard Fawn W. Tims, 1312 1/12/2018 land Breeze Ln., San Mind Over Matter Mar- Liability Company. The BUSINESS NAME St., Apt. E-16, Chula Indian Creek Pl., Chula Signature: Diego, CA 92154. This keting Inc., 1631 Cop- first day of business STATEMENT NO. Vista, CA 91911. Re- Vista, CA 91915. This Heather Harrison business is conducted per Penny Dr., Chula was: 12/27/2017 2018-9001408 gistrant: Isidro Israel business is conducted Statement filed with by: Individual. -

Wspó£Czesne Metody Opracowania Baz Danych

Pawlicki, B. M., Czechowicz, J., Drabowski, M. (2001). Modern methods of data processing of old historical structure for the needs of the Polish Information System About Monuments following the example of Cracow in Cultural Heritage Protection. In: D. Kereković, E. Nowak (ed.). GIS Polonia 2001. Hrvatski Informatički Zbor – GIS Forum, Croatia, 367-378. MODERN METHODS OF DATA PROCESSING OF OLD HISTORICAL STRUCTURE FOR THE NEEEDS OF THE POLISH INFORMATION SYSTEM ABOUT MONUMENTS FOLLOWING THE EXAMPLE OF CRACOW IN CULTURAL HERITAGE PROTECTION Bonawentura Maciej PAWLICKI Jacek CZECHOWICZ Mieczysław DRABOWSKI Politechnika Krakowska Cracow University Of Technology Cracow University of Technology, Institute of History of Architecture and Monuments Preservation, Center of Education and Research in the Range of Application of Informatic Systems, Cracow ABSTRACT Presented works were made from 1999 to 2001 years in the Division of Conservatory Studies and Researches, of the Institute of History of Architecture and Monument Preservation - Faculty of Architecture of the Cracow University of Technology. The software, methods and models of the data base systems were laboratory experimented in the Computer Information Systems Center of the Cracow University of Technology. The works (laboratories, terain exercises and student practises) which have been doing so far, concerned of geodesy-cataloguing registration and using computer technology give an optimal possibilities of monitoring of the historical environment for preservation of the cultural heritage. The data used in computer modelling make applying of multiply materials as a basis of data warehouse, among other: geodesy foundations, their newest actualisation, digital camera photography’s and space visualisations. In works students used following graphical programs: GIS, 3D Studio Max, AutoCAD – Architectural Desktop, ArchiCAD 6.5, Adobe Photo Shop, Land Development, Corel Draw, Picture Publisher. -

Development of Form Making of Door Knockers in Italy in the Xv-Xvii Centuries

Man In India, 96 (12) : 5677-5697 © Serials Publications DEVELOPMENT OF FORM MAKING OF DOOR KNOCKERS IN ITALY IN THE XV-XVII CENTURIES Tatiana Evgenievna Trofimova* Abstract: Decorative art items - door knockers - combine practical and esthetic features. At the same time they are a part of everyday and art culture, and can tell much about the ideology, lifestyle of the society, and the level of the artistic crafts development at the time when they were created. The goal of this research is to study the role and purpose of door knockers in the Italian culture of the XV-XVII centuries, to research door knockers that continue decorating doors of various Italian cities and towns, to study in details Italian door knockers of the golden age of the bronze-casting art through the samples from the Hermitage in Saint-Petersburg. For this research it was necessary to solve the following tasks: to put the generalized illustrative material in the historical succession, to consider form making of door knockers in accordance with the architectural styles, and symbolic meaning, to define characteristic features of the artistic expression, to reveal regularities in form making and decorating of door knockers, as well as to study and describe samples from the Hermitage in Saint-Petersburg as the best examples of Italian door knockers of the XV-XVII centuries. The following methods were used during the research: - References and analytical: reproduction of the general picture of the development of various forms of door knockers, searching for and systematization -

Predictive Direct Flux Control—A New Control Method of Voltage Source Inverters in Distributed Generation Applications

energies Article Predictive Direct Flux Control—A New Control Method of Voltage Source Inverters in Distributed Generation Applications Jiefeng Hu Department of Electrical Engineering, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China; [email protected]; Tel.: +852-2766-6140 Academic Editor: Frede Blaabjerg Received: 16 February 2017; Accepted: 21 March 2017; Published: 23 March 2017 Abstract: Voltage source inverters (VSIs) have been widely utilized in electric drives and distributed generations (DGs), where electromagnetic torque, currents and voltages are usually the control objectives. The inverter flux, defined as the integral of the inverter voltage, however, is seldom studied. Although a conventional flux control approach has been developed, it presents major drawbacks of large flux ripples, leading to distorted inverter output currents and large power ripples. This paper proposes a new control strategy of VSIs by controlling the inverter flux. To improve the system’s steady-state and transient performance, a predictive control scheme is adopted. The flux amplitude and flux angle can be well regulated by choosing the optimum inverter control action according to formulated selection criteria. Hence, the inverter flux can be controlled to have a specified magnitude and a specified position relative to the grid flux with less ripples. This results in a satisfactory line current performance with a fast transient response. The proposed predictive direct flux control (PDFC) method is tested in a 3 MW high-power grid-connected VSI system in the MATLAB/Simulink environment, and the results demonstrate its effectiveness. Keywords: voltage source inverter (VSI); predictive control; inverter flux 1. Introduction Pulse width modulation (PWM) voltage source inverters (VSIs) have been widely used in power electronics, and their control has been extensively studied in the last decades. -

Scavenger Hunt Glossary

GLOSSARY DOWNTOWN NORFOLK VIRTUAL SCAVENGER HUNT A Hampton Roads Chapter of the American Institute of Architecture HISTORIC PRESERVATION MONTH EVENT May 15-31, 2020 Architecture has a language unto itself. Every piece of a building, every type of ornamentation, every style has a distinct name and so does each detail you will encounter in our Scavenger Hunt. Below are definitions of typical architectural features you will see in the photos embedded in the Virtual Scavenger Hunt Interactive Map and the Official Virtual Scavenger Hunt Entry Form. Choose from these definitions for the description that is the best match to the details to be found. Enter this on the Entry Form (see example on the bottom right of the Official Entry Form). HINT: Not all are used; some are used more than once. Acroterion – A classical ornament or crowning adorning a pediment Fleuron – Ornament at the center of the Ionic abacus. Classically usually at gable corners and crown, generally carvings of monsters, it is a floral ornament, but in modern interpretations, can be sphinxes, griffins or gorgons, sometimes massive floral complexes. anthropomorphic (e.g. human forms). Art Deco Ornament – Popular decorative arts in the 1920s–30s Fretwork – Ornament comprised of incised or raised bans, variously after WWI. Identified by geometric, stylized, designs and surface combined and typically using continuous lines arranged in a ornamentation in forms such as zigzags, chevrons and stylized floral rectilinear or repeated geometric pattern. Also called a Meander. motifs. Geison – The projection at the bottom of the tympanum formed by Bas Relief Ornamentation – Carved, sculpted or cast ornament the top of the Cornice. -

Artistic Furnishings and Interior Decorations of The

A RT I ST I C F U R N I S H I N GS A N D I N T E R I O R DE C O R AT I O N S OF T H E R E S I DE N C E H E N R W P R E Y . O O , SQ . T O B E S O L D A T U N R E ST R I C T E D P U B L I C S A L E B M A E . K I R B Y Y M R . T H O S O F T H E A M E R I C A N A R T A S S OC I A T I O N , M A N A G E R S ON P U BL I C VI EW M D A Y A N D T DA Y A PR I L 19T H A N D 20T H ON U E S , M . N T I L P . M . F R OM 10 A . U 5 D SS ON T O T H E EXH B ON AN D S LE EX LUS VELY (A MI I I ITI A , C I BY D T O BE H AD N CAR , O WRITTEN APPLICATION T O T H E MAN AG ERS) T H E A R T I ST I C P R O P E R T Y CON TAIN ED I N T H E RESIDEN CE OF E . -

Szlachta Sieradzka XIX Wieku Herbarz Wersja Poprawiona 2017 R

Elżbieta Halina Nejman P Szlachta Sieradzka XIX wieku Herbarz Wersja poprawiona 2017 r. 499 P A C I O R K O W S K I PACIORKOWSKI h.Gryf Herb Gryf złoty w czerwonym polu trzymający w jednej szponie trąbę myśliwską, nad koroną podobnyż Gryf przez połowę w prawą tarczy obrócony. Dom ten w sieradzkim województwie, z których Dominik miał za sobą Danielę Rakowską, z którą spłodził syna Marcina. (Nieiecki) Marcin nobilitowany w 1768 r. & Anna Tomicka, 2v. Anna Wojciechowska, A. Teresa (1) franciszkanka, B. Wiktoria (1) franciszkanka, C. ks. Jan Gabriel (1) proboszcz kolski i brzeźnicki, D. Józef Dominik (1) Brygida Sadrini, 1.Anna † 1888 2.Antoni 3.Walenty E. Apolonia (2) & 1775.II.17 Dobryszyce, Jan Pobóg Pągowski, dz. wsi Golanki, s. Feliksa i Katarzyny Zdańskiej, F. Antoni Michał burgrabia chęciński, dz. d. Przystajń c.d. Tabl.1 G. Marianna (2) & a.1760, Józef v. Florian Dąbrowski *1721, s. Marcina, z Woli Jedlińskiej, 2v..Konstancja Sokołowska, H. Ksawery Franciszek (2) & Rozalia Repetowska, 2v.Barbara Pobóg Męcińska † a.1828, c. Stanisława i Rozali Kurdwanowskiej, 2v.1803 Borowno, Seweryn Walgdon sędzia pokoju p. wieluńskiego, (USC Borowno) 1.Feliks (1) 2.Ludwik (1) bpt., dz. Borowna w p. ostrzeszowskim, 3.Andrzej (1) 4.Antonilla (1) dz. Wikłowa par. Kruszyna, (Lisiecki1814 k.150) 5.Józefa (2) & Paweł Czarnecki, 6.Tekla Apolonia (1) † a. 1818 & 1809 Borowno, Jacek Roch Fundament Karśnicki s. Konstantego i Teresy Rozwadowskiej, 2v.1814 Józef Seloff z Lipnika (Lisiecki1818 II k.742, USC Borowno) 7.Stanisław (2) 1794-1847& Izabela Morzkowska, c. Ignacego Piotra i Anny Męcińskiej, (Lisiecki 1828 II) a).Ignacy & Wanda Paciorkowska, c. -

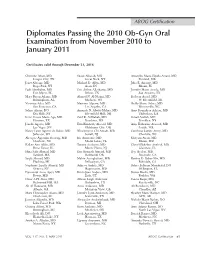

Diplomates Passing the 2010 Ob-Gyn Oral Examination from November 2010 to January 2011

ABOG Certification Diplomates Passing the 2010 Ob-Gyn Oral Examination from November 2010 to January 2011 Certificates valid through December 31, 2016 Christine Abair, MD Susan Alkasab, MD Amaryllis Maria Elpida Arraut, MD League City, TX Great Neck, NY Portland, OR Janet Abrams, MD Michael D. Allen, MD Julio E. Arronte, MD Rego Park, NY Avon, IN Miami, FL Fadi Abushahin, MD Eric Arthur Allerkamp, MD Jennifer Marie Arzola, MD Fort Myers, FL Belton, TX San Antonio, TX Mary Bryan Adams, MD Ahmed N. Al-Niaimi, MD Radwan Asaad, MD Birmingham, AL Madison, WI W. Bloomfield, MI Veronica Ades, MD Mariann Alperin, MD Shelly Marie Asbee, MD San Francisco, CA Los Angeles, CA Mooresville, NC Salma Afroze, DO Amanda N. Alvelo-Malina, MD Amy Roundtree Ashton, MD Dix Hills, NY Bloomfield Hills, MI Thibodaux, LA Irene Eseese Marie Aga, MD Zaid R. Al-Wahab, MD Fouad Atallah, MD Houston, TX Dearborn, MI Brooklyn, NY Janelle Agosto, MD Erin Kimberly Alward, MD Amy Katharine Atwood, MD Las Vegas, NV Oklahoma City, OK Seattle, WA Nancy Lynn Aguirre de Baker, MD Nkechinyere Chi Amadi, MD Caudrean Latiste Avery, MD Jefferson, WI Sewell, NJ Charlotte, NC Aboagye Agyenim-Boateng, MD Iris Amarante, MD Maryam Awan, MD Charlotte, NC Miami Lakes, FL Elkton, MD KaLee Ann Ahlin, MD Tatiana Ambarus, MD Cheryl Ekkebus Axelrod, MD River Forest, IL Morris Plains, NJ Glenview, IL Hina Safir Ahmad, MD Eric Kenneth Amend, MD Roy Ayalon, MD Sanford, ME Redmond, OR Riverside, CA Saqib Ahmad, MD Mahin Amirgholami, MD Katrina D. Baker-Nix, MD Flushing, MI Bellcanyon, CA Palmdale, CA Stephanie Lucille Ahmed, MD Adjoavi Andele, MD Debra Balliram-Manohalal, DO Geneva, NY Hagerstown, MD Wellington, FL Funminiyi Anne Ajayi, MD Krista Jean Anders, MD Steven Banks, MD Bowie, MD Erda, UT Poulsbo, WA Cinar A.H. -

ADP Bulletin 92 Mars 2020 P4-26 Les Mascarons

Bull 92 mars 2020 DEF Boby_Mise en page 1 17/03/20 22:41 Page4 PATRIMOINE Les mascarons de Pézenas Une touche de fantaisie et d’élégance Ces têtes ou masques de fantaisie sculptés décorent les clefs d’arcade, les fontaines, les portes. L’usage de ces visages remonte à l’Antiquité. Ils avaient un rôle protecteur, ils étaient censés éloigner les démons. Au Moyen Âge l’usage des sculptures aux représentations démoniaques enrichit le répertoire décoratif de ces visages de pierre. Au XV e siècle, suite à la découverte des peintures antiques de la Villa Auréa à Rome, appelées “grotteschi“, la Renaissance italienne va remettre au goût du jour ce répertoire ornemental. Les artistes italiens venus travailler pour François 1 er à Fontainebleau vont s’en inspirer. Les recueils de gravures de l’architecte Jacques Androuet du Cerceau vont également contribuer à la diffusion de ces ornements. À Versailles, au XVII e siècle on voit apparaître de nouveaux modèles qui vont enrichir le genre. Le XVIII e siècle, la grande mode des mascarons Au XVIII e siècle, le goût de la fantaisie, de l’exotisme, l’embellissement du cadre de vie, vont faire du mascaron un des ornements incontournables de l’architecture et de la modénature des façades. Toutes les villes vont se l’approprier et Pézenas ainsi que les villages de la basse vallée de l’Hérault n’y dérogent pas. Le mascaron, symbole identitaire, de notoriété va donc devenir très tendance. Hôtel Darles de Chamberlain. Les mascarons au XIX e siècle Un mascaron : c’est quoi ? Le trop plein de mascarons sur les façades au Un mascaron est un ornement sculpté XVIII e siècle va être décrié et ils vont peu à peu représentant un visage humain, animal, tomber en désuétude et disparaître progressi- fantastique ou grotesque. -

“Raid the Icebox Now,” Triple Canopy

To Make New Bodies Out of Old Shapes Triple Canopy For “Raid the Icebox Now,” Triple Canopy created Can I Leave You?, a multimedia installation that responds to the RISD Museum’s Pendleton House, which was built in 1906 to exhibit the bequest (and resemble the nearby home) of the collector Charles Pendleton. This volume revises the lavish catalogue of Pendleton’s collection, published by the museum in 1906 in a limited edition featuring photogravure illustrations. Triple Canopy focuses on the catalogue’s text, a seemingly anodyne description of styles and techniques. This language, however, is a manifestation of the rhetoric around taste, distinction, and progress, especially in industry and art, that has fueled the formation of American identity and abetted the exercise of American power. As To Make New Bodies Out of Old Shapes progresses, the original catalogue is increasingly augmented by nationalistic speeches, nostalgic stories, messianic sermons, and other original sources that reflect this underlying agenda. Dutiful assessment of the collection is interrupted by a time traveler who meddles with the rebellion against the British, an enslaved person harvesting mahogany to furnish the homes of New England aristocrats, and a Chinese philosopher disturbed by the patrician penchant for dragons and pagodas. Eventually, To Make New Bodies Out of Old Shapes gives itself over to these accounts. THE PENDLETON COLLECTION PUBLISHED BY THE RHODE ISLAND SCHOOL OF DESIGN Copyright, 1904 By Luke Vincent Lockwood THE RHODE ISLAND SCHOOL OF DESIGN CERTIFIES THAT ONLY l6o COPIES OF THIS BOOK HAVE BEEN PRINTED, AND THE TYPE DISTRIBUTED. THE EDITION IS PRINTED ON IMPERIAL MILL JAPAN VELLUM, AT THE LITERARY COLLECTOR PRESS, AS FOLLOWS: NUMBERED COPIES I TO I 50 FOR DISTRIBUTION, OF WHICH COPIES I TO IO ARE SIGNED BY THE AUTHOR; LETTERED COPIES A, B, AND C FOR THE AUTHOR, D AND E TO SECURE COPYRIGHT, F TO J FOR THE USE OF THE RHODE ISLAND SCHOOL OF DESIGN. -

Center 8 Research Reports and Record of Activities

National Gallery of Art Center 8 Research Reports and Record of Activities ¢ am I, ~i.,r .~,4, I , ~, - ....... "It. ",2.'~'~.~D~..o~ ~', ~, : -- "-';"~-'~"'-" tl..~" '~ ' -- ~"' ',"' ." , ~. " ;-.2. ; -,, '6.~ h'.~ ~,,.'.~ II,,..~'.~..~.->'. "~ ;..~,,r~,; .,.z . - -~p__.~..i..... • , ". ~:;° ..' = : .... ..i ~ '- 3:.,'~<'~- i £ :--.-_ National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Center 8 Research Reports and Record of Activities June 1987-May 1988 Washington, 1988 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, D.C. 20565 Telephone: (202) 842-6480 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565. Copyright © 1988 Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This publication was produced by the Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Frontispiece: Thomas Rowlandson, Viewing at the Royal Academy, c. 1815, Paul Mellon Collection, Upperville, Virginia. CONTENTS General Information Fields of Inquiry 9 Fellowship Program 10 Facilities 12 Program of Meetings 13 Publication Program 13 Research Programs 14 Board of Advisors and Selection Committee 14 Report on the Academic Year 1987-1988 Board of Advisors 16 Staff 16 Architectural Drawings Cataloguing Project 16 Members 17 Meetings 21 Lecture Abstracts 32 Members' Research Reports Reports 38 ~llpJ~V~r ' 22P 'w x ~ i~ ~i!~i~,~ ~ ~ ~ ~!~,~!~!ii~!iii~ ~'~,i~ ~ ~ ~i~, ~ HE CENTER FOR AI)VANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS was founded T in 1979, as part of the National Gallery of Art, to promote the study of history, theory, and criticism of art, architecture, and urbanism through the formation of a community of scholars.