Assessing the Role of the Private Sector in Surveillance For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 Secretary General César Gaviria

Electoral Observations in the Americas Series, No. 13 Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 Secretary General César Gaviria Assistant Secretary General Christopher R. Thomas Executive Coordinator, Unit for the Promotion of Democracy Elizabeth M. Spehar This publication is part of a series of UPD publications of the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States. The ideas, thoughts, and opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the OAS or its member states. The opinions expressed are the responsibility of the authors. OEA/Ser.D/XX SG/UPD/II.13 August 28, 1998 Original: Spanish Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 General Secretariat Organization of American States Washington, D.C. 20006 1998 Design and composition of this publication was done by the Information and Dialogue Section of the UPD, headed by Caroline Murfitt-Eller. Betty Robinson helped with the editorial review of this report and Jamel Espinoza and Esther Rodriguez with its production. Copyright @ 1998 by OAS. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced provided credit is given to the source. Table of contents Preface...................................................................................................................................vii CHAPTER I Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER II Pre-election situation .......................................................................................................... -

A Revision of the Genus Audantia of Hispaniola with Description of Four New Species (Reptilia: Squamata: Dactyloidae)

NOVITATES CARIBAEA 14: 1-104, 2019 1 A REVISION OF THE GENUS AUDANTIA OF HISPANIOLA WITH DESCRIPTION OF FOUR NEW SPECIES (REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: DACTYLOIDAE) Una revisión del género Audantia de la Hispaniola con descripción de cuatro especies nuevas (Reptilia: Squamata: Dactyloidae) Gunther Köhler1a,2,*, Caroline Zimmer1b,2, Kathleen McGrath3a, and S. Blair Hedges3b 1 Senckenberg Forschungsinstitut und Naturmuseum, Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt A.M., Germany. 1a orcid.org/0000-0002-2563-5331; 2 Goethe-University, Institute For Ecology, Evolution & Diversity, Biologicum, Building C, Max-Von-Laue-Str. 13, 60438 Frankfurt Am Main, Germany. 3 Center For Biodiversity, Temple University, Serc Building Suite 502, 1925 N 12th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19122, U.S.A.; 3a orcid.org/0000-0002-1988-6265; 3b orcid.org/0000-0002-0652-2411. * Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT We revise the species of Audantia, a genus of dactyloid lizards endemic to Hispaniola. Based on our analyses of morphological and genetic data we recognize 14 species in this genus, four of which we describe as new species (A. aridius sp. nov., A. australis sp. nov., A. higuey sp. nov., and A. hispaniolae sp. nov.), and two are resurrected from the synonymy of A. cybotes (A. doris comb. nov., A. ravifaux comb. nov.). Also, we place Anolis citrinellus Cope, 1864 in the synonymy of Ctenonotus distichus (Cope, 1861); Anolis haetianus Garman, 1887 in the synonymy of Audantia cybotes (Cope, 1863); and Anolis whitemani Williams, 1963 in the synonymy of Audantia saxatilis (Mertens, 1938). Finally, we designate a lectotype for Anolis cybotes Cope, 1863, and for Anolis riisei Reinhardt & Lütken, 1863. -

Anolis Cybotes Group)

Evolution, 57(10), 2003, pp. 2383±2397 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF ECOLOGICAL AND MORPHOLOGICAL DIVERSIFICATION IN HISPANIOLAN TRUNK-GROUND ANOLES (ANOLIS CYBOTES GROUP) RICHARD E. GLOR,1,2 JASON J. KOLBE,1,3 ROBERT POWELL,4,5 ALLAN LARSON,1,6 AND JONATHAN B. LOSOS1,7 1Department of Biology, Campus Box 1137, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri 63130-4899 2E-mail: [email protected] 3E-mail: [email protected] 4Department of Biology, Avila University, 11901 Wornall Road, Kansas City, Missouri 64145-1698 5E-mail: [email protected] 6E-mail: [email protected] 7E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Anolis lizards in the Greater Antilles partition the structural microhabitats available at a given site into four to six distinct categories. Most microhabitat specialists, or ecomorphs, have evolved only once on each island, yet closely related species of the same ecomorph occur in different geographic macrohabitats across the island. The extent to which closely related species of the same ecomorph have diverged to adapt to different geographic macro- habitats is largely undocumented. On the island of Hispaniola, members of the Anolis cybotes species group belong to the trunk-ground ecomorph category. Despite evolutionary stability of their trunk-ground microhabitat, populations of the A. cybotes group have undergone an evolutionary radiation associated with geographically distinct macrohabitats. A combined phylogeographic and morphometric study of this group reveals a strong association between macrohabitat type and morphology independent of phylogeny. This association results from long-term morphological evolutionary stasis in populations associated with mesic-forest environments (A. c. cybotes and A. marcanoi) and predictable morphometric changes associated with entry into new macrohabitat types (i.e., xeric forests, high-altitude pine forest, rock outcrops). -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 4973 l-DO PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$30.5 MILLION TO THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC FOR A HEALTH SECTOR REFORM APL 2 (PARSS2) PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized August 20,2009 This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the Public Disclosure Authorized performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective: 06/17/2009 -Appraisal stage) Currency Unit = Dominican Pesos RD$35.85 = US$1 US$O.O28 = RD$1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AAA Analytic and Advisory Activities ADOPEM Dominican Association for Women Development (Asociacidn Dominicana para el Desarrollo de la Mujer) AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome APL Adaptable Program Loan ARCS Audit Report Compliance System BCG Bacillus Calmette-GuCrin (or Bacille Calmette-GuCrin, BCG) Tuberculosis Vaccine BCRD Central Bank of the Dominican Republic BHD Banco Hipotecario Dominicano BMT Monthly Based Transfer CCT Conditional Cash Transfer CERSS Executive Commission for Health Sector Reform (Comisidn Ejecutivapara la Reforma del Sector Salud) CESDEM Center for Social and Demographic Studies (Centro de Estudios Sociales y Demogrdficos) CMU Country Management Unit COPRESIDA Presidential Commission for Fight Against HIV/AIDS (Consejo Presidencial del SIDA) CPIA Country Policy -

Pearly-Eyed Thrasher) Wayne J

Urban Naturalist No. 23 2019 Colonization of Hispaniola by Margarops fuscatus Vieillot (Pearly-eyed Thrasher) Wayne J. Arendt, María M. Paulino, Luis R. Pau- lino, Marvin A. Tórrez, and Oksana P. Lane The Urban Naturalist . ♦ A peer-reviewed and edited interdisciplinary natural history science journal with a global focus on urban areas ( ISSN 2328-8965 [online]). ♦ Featuring research articles, notes, and research summaries on terrestrial, fresh-water, and marine organisms, and their habitats. The journal's versatility also extends to pub- lishing symposium proceedings or other collections of related papers as special issues. ♦ Focusing on field ecology, biology, behavior, biogeography, taxonomy, evolution, anatomy, physiology, geology, and related fields. Manuscripts on genetics, molecular biology, anthropology, etc., are welcome, especially if they provide natural history in- sights that are of interest to field scientists. ♦ Offers authors the option of publishing large maps, data tables, audio and video clips, and even powerpoint presentations as online supplemental files. ♦ Proposals for Special Issues are welcome. ♦ Arrangements for indexing through a wide range of services, including Web of Knowledge (includes Web of Science, Current Contents Connect, Biological Ab- stracts, BIOSIS Citation Index, BIOSIS Previews, CAB Abstracts), PROQUEST, SCOPUS, BIOBASE, EMBiology, Current Awareness in Biological Sciences (CABS), EBSCOHost, VINITI (All-Russian Institute of Scientific and Technical Information), FFAB (Fish, Fisheries, and Aquatic Biodiversity Worldwide), WOW (Waters and Oceans Worldwide), and Zoological Record, are being pursued. ♦ The journal staff is pleased to discuss ideas for manuscripts and to assist during all stages of manuscript preparation. The journal has a mandatory page charge to help defray a portion of the costs of publishing the manuscript. -

Download Vol. 21, No. 1

BULLETIN of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences Volume 21 1976 Number 1 VARIATION AND RELATIONSHIPS OF SOME HISPANIOLAN FROGS (LEPTODACTYLIDAE, ELEUTHERODACTYLUS ) OF THE RICORDI GROUP ALBERT SCHWARTZ .A-' UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM, BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, are published at irregular intervals. Volumes contain about 300 pages and are not necessarily completed in any one calendar year. CARTER R. GILBERT, Editor RHODA J. RYBAK, Managing Editor Consultant for this issue: ERNEST E. WILLIAMS Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publications and all manu- scripts should be addressed to the Managing Editor of the Bulletin, Florida State Museum, Museum Road, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611. This public document was promulgated at an annual cost of $1647.38 or $1.647 per copy. It makes available to libraries, scholars, and all interested persons the results of researchers in the natural sciences, emphasizing the Circum-Caribbean region. Publication date: Aug. 6, 1976 Price: $1.70 VARIATION AND RELATIONSHIPS OF SOME HISPANIOLAN FROGS ( LEPTODACTYLIDAE, ELEUTHERODACTYLUS) OF THE RICORDI GROUP ALBERT SCHWARTZ1 SYNOPSIS: Five species of Hispaniolan Eleutherodactylus of the ricordi group are discussed, and variation in these species is given in detail. The relationships of these five species, both among themselves and with other Antillean members of the ricordi group, are treated, and a hypothetical sequence of inter- and intra-island trends is given, -

8. Coastal Fisheries of the Dominican Republic

175 8. Coastal fisheries of the Dominican Republic Alejandro Herrera*, Liliana Betancourt, Miguel Silva, Patricia Lamelas and Alba Melo Herrera, A., Betancourt, L., Silva, M., Lamelas, P. and Melo, A. 2011. Coastal fisheries of the Dominican Republic. In S. Salas, R. Chuenpagdee, A. Charles and J.C. Seijo (eds). Coastal fisheries of Latin America and the Caribbean. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper. No. 544. Rome, FAO. pp. 175–217. 1. Introduction 176 2. Description of fisheries and fishing activities 178 2.1 Description of fisheries 178 2.2 Fishing activity 188 3. Fishers and socio-economic aspects 191 3.1 Fishers’ characteristics 191 3.2 Social and economic aspects 193 4. Community organization and interactions with other sectors 194 4.1 Community organization 194 4.2 Fishers’ interactions with other sectors 195 5. Assessment of fisheries 197 6. Fishery management and planning 199 7. Research and education 201 7.1. Fishing statistics 201 7.2. Biological and ecological fishing research 202 7.3 Fishery socio-economic research 205 7.4 Fishery environmental education 206 8. Issues and challenges 206 8.1 Institutionalism 207 8.2 Fishery sector plans and policies 207 8.3 Diffusion and fishery legislation 208 8.4 Fishery statistics 208 8.5 Establishment of INDOPESCA 208 8.6 Conventions/agreements and organizations/institutions 209 References 209 * Contact information: Programa EcoMar, Inc. Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. E-mail: [email protected] 176 Coastal fisheries of Latin America and the Caribbean 1. INTRODUCTION In the Dominican Republic, fishing has traditionally been considered a marginal activity that complements other sources of income. -

Reptilla: Sauria: Iguanidae

~moo~~~~oo~~moo~ ~oorn~m~m~~ rnoo~rnrnm~m~~ Number 47 December 30, 1981 Variation in Hispaniolan Anolis olssoni Schmidt (Reptilia: Sauria: Iguanidae) Albert Schwartz REVIEW COMMITTEE FOR THIS PUBLICATION: Ronald Crombie, National Museum of Natural History Robert Henderson, Milwaukee Public Museum Richard Thomas, University of Puerto Rico ISBN 0·89326·077·0 Accepted for publication November 11, 1981 Milwaukee Public Museum Publications Published by the order of the Board of Trustees Milwaukee Public Museum 800 West Wells Street Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53233 Variation in Hispaniolan Anolis olssoni Schmidt (Reptilia: Sauria: Iguanidae) Albert Schwartz Miami-Dade Community College North Campus, Miami, Florida 33167 ABSTRACT - The Hispaniolan "grass anole," Anolis olssoni Schmidt, is widespread on the Hispaniolan north island and has invaded the south island Peninsula de Barahona and De de la Gonave. Although these lizards are xerophilic, their dorsal color and pattern are not always pale as is typical of desert lizards. Seven subspecies are recognized on the main island and another on De de la Gonave. These differ in color, pattern, and scutellation, and at least two are apparently widely disjunct from other populations. Two Dominican and two Haitian populations are left unassigned subspecifically, primarily due to inadequate samples. On the Greater Antillean islands of Hispaniola, Cuba, and Puerto Rico is a complex of anoles which have come to be called" grass anoles" due to their habitat. The head and body shapes, as well as their very elongate tails, make these anoles conform to the shapes of blades of grass, although they are not rigidly restricted to this sort of physical situation. -

Limnothlypis Swainsonii) from Hispaniola

ADDITIONAL NOTES ON THE WINTERING STATUS OF SWAINSON’S WARBLER IN THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 1 2 CHRISTOPHER C. RIMMER AND JESÚS ALMONTE 1Vermont Institute of Natural Science, 27023 Church Hill Road, Woodstock, VT 05091, USA; and 2Fundación Moscoso Puello, Apartado Postal No. 1986, Zona 1, Santo Domingo, República Dominicana Abstract. – We report the third and fourth records of Swainson’s Warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii) from Hispaniola. All four records have involved mist-netted birds in montane broadleaf forests of Sierra de Bahoruco in the Dominican Republic. The species has never been recorded during extensive ornitho- logical field studies in a variety of shrub-scrub and forested habitats elsewhere in the country. Although Swainson’s Warblers use a range of habitats on other Greater Antillean islands, we believe that the spe- cies’ Hispaniolan distribution may be largely or exclusively confined to high elevation broadleaf forests. We further believe that Swainson’s Warbler should be considered a regular, if local and uncommon, win- ter resident in the Dominican Republic. We encourage focused investigations, using tape-recorded play- backs and mist-netting, of the distribution and habitat associations of this species in other regions of His- paniola. Resumen. – NOTAS ADICIONALES SOBRE EL ESTADO DE RESIDENCIA INVERNAL DE LA CIGÜITA DE SWAINSON EN LA REPÚBLICA DOMINICANA. Reportamos el tercer y cuarto registro de la Cigüita de Swain- son (Limnothlypis swainsonii) en La Española. Los cuatro registros han sido de aves capturadas en redes en el bosque montano latifolio de la sierra de Bahoruco en la República Dominicana. La especie nunca ha sido observada durante investigaciones ornitológicas extensas efectuadas en diversos hábitats arbustivos y boscosos en otras partes del país. -

Zootaxa: a Review of the Asilid (Diptera) Fauna from Hispaniola

ZOOTAXA 1381 A review of the asilid (Diptera) fauna from Hispaniola with six genera new to the island, fifteen new species, and checklist AUBREY G. SCARBROUGH & DANIEL E. PEREZ-GELABERT Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand AUBREY G. SCARBROUGH & DANIEL E. PEREZ-GELABERT A review of the asilid (Diptera) fauna from Hispaniola with six genera new to the island, fifteen new species, and checklist (Zootaxa 1381) 91 pp.; 30 cm. 14 Dec. 2006 ISBN 978-1-86977-066-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-067-9 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2006 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2006 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 1381: 1–91 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1381 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A review of the asilid (Diptera) fauna from Hispaniola with six genera new to the island, fifteen new species, and checklist AUBREY G. SCARBROUGH1 & DANIEL E. PEREZ-GELABERT2 1Visiting Scholar, Department of Entomology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85741. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Entomology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P. -

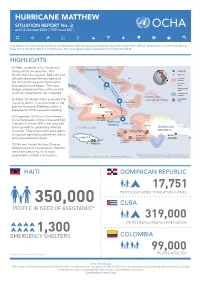

HURRICANE MATTHEW SITUATION REPORT No

HURRICANE MATTHEW SITUATION REPORT No. 2 as of 4 October 2016 (1700 hours EST) This report is produced by OCHA in collaboration with humanitarian partners and with inputs from official institutions. It covers the period from 3 to 4 October 2016 at 17:00 hours. The next report will be published on 5 October 2016. HIGHLIGHTS Forecast track and possible influence (as of 4 Oct 2016) • In Haiti, torrential rains, floods and BAHAMAS strong winds are reported. The Capital city Government has issued a Red alert and Major city officially requested the assistance of Hurricane warning the UN and its support mechanisms. 5 Oct, 2pm Hurricane Evacuations have begun. The main projected track watch Tropical storm bridge connecting Port-au-Prince with watch southern departments has collapsed. Tropical storm warning TURKS AND • Coordination In Cuba, the Government activated the CAICOS ISLANDS hubs 5 Oct, 2am “cyclonic alarm” in six provinces of the CUBA east for Hurricane Matthew, which is Holguin expected to hit the area this evening. Guantanamo • UN agencies, NGOs and the Interna- Santiago tional Federation of Red Cross and Red de Cuba Hurricane Crescent Societies (IFRC) are prepared 4 Oct, 5pm Matthew HAITI to bring relief to potentially affected Caribbean Sea DOMINICAN countries. They have mobilized experts Port-au-Prince REPUBLIC Jérémie to support national humanitarian teams (UNDAC) OCHA office Santo and pre-positioned stocks. JAMAICA MINUSTAH Domingo UNDAC Les Cayes UNDAC (UNDAC) • OCHA and United Nations Disaster Kingston Assessment and Coordination (UNDAC) teams are preparing initial rapid The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map assessments in Haiti and Jamaica. -

A Revision of the Genus Diastolinus Mulsant and Rey

A REVISION OF THE GENUS DIASTOLINUS MULSANT AND REY (COLEOPTERA: TENEBRIONIDAE) OF THE WEST INDIES by Charles Jay Hart A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Charles Jay Hart 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my incredibly supportive Mother and Father for always encouraging me no matter the difficulty. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks go to Michael Ivie who guided and supported me through this difficult project. I am grateful for the useful comments on the draft of this document from my committee members Kevin O’Neill, and Matt Lavin. I am thankful for the support of all of the institutions, collection managers and curators listed under Material Examined that loaned specimens to make this project possible. I am grateful for all of their efforts. Special thanks to Maxwell Barclay, Doug Yanega, Patrice Bouchard, Neal Evenhuis, and Frank.Krell for nomenclatural advice. Thanks to Johannes Bergsten for photographing the Diastolinus tibidens holotype. Frank Etzler, Vinicius Ferreira, and Amy Dolan provided much support and fruitful discussions. Thanks to Ladonna Ivie for providing support and delicious snacks at the lab. I am especially appreciative of my wife, An Nguyen, for her help with edits and figures. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. A REVISION OF THE GENUS DIASTOLINUS MULSANT AND REY (COLEOPTERA: TENEBRIONIDAE) OF THE WEST INDIES.................................1 Contribution