This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

1 Old, Unhappy, Far-Off Things a Little Learning

1 Old, Unhappy, Far-off Things A Little Learning I have not been in a battle; not near one, nor heard one from afar, nor seen the aftermath. I have questioned people who have been in battle - my father and father-in-law among them; have walked over battlefields, here in England, in Belgium, in France and in America; have often turned up small relics of the fighting - a slab of German 5.9 howitzer shell on the roadside by Polygon Wood at Ypres, a rusted anti-tank projectile in the orchard hedge at Gavrus in Normandy, left there in June 1944 by some highlander of the 2nd Argyll and Sutherlands; and have sometimes brought my more portable finds home with me (a Minie bullet from Shiloh and a shrapnel ball from Hill 60 lie among the cotton-reels in a painted papier-mache box on my drawing-room mantelpiece). I have read about battles, of course, have talked about battles, have been lectured about battles and, in the last four or five years, have watched battles in progress, or apparently in progress, on the television screen. I have seen a good deal of other, earlier battles of this century on newsreel, some of them convincingly authentic, as well as much dramatized feature film and countless static images of battle: photographs and paintings and sculpture of a varying degree of realism. But I have never been in a battle. And I grow increasingly convinced that I have very little idea of what a battle can be like. Neither of these statements and none of this experience is in the least remarkable. -

Goxhill Memorial Hall Future Programme - 7Pm – 10Pm Admission £5 Which Includes September 8Th We Welcome Sue Hawksmoor to Cottage Pie and Pea Supper

orgive me for using so much of this issue on stories about the First World War and how people from Goxhill were involved in it. 100 years since the start on August 4th 1914, is well beyond F most people’s living memories. My parents were around then as children, yet never spoke to me of their memories of the Great War, or much about the Second World War. But the impact made by the sacrifices, not just of those directly involved in the war, but all those left behind to take on the work load of the men away fighting and keeping the home and family together, is everlasting. Women especially rose to the challenge of doing work previously only done by men, hard physical and skilled engineering work of all kinds. The world of work and expectations of equality were first sewn during this period and has resulted in all the progress in society since and the equal opportunities and responsibilities open to all today. It also eventually led to peace in Europe, unfortunately only after yet another World War. It is only through the stories of people who died and those who survived the war, that we can gain a more personal insight into what it was really like behind all those terrible statistics and names of places of significance that we have been told about. These were real people, with real families living in villages just like ours. Joining together in groups from their area, friends and colleagues enlisting in groups such as the Grimsby Chums. -

Magazine Magazine

MAGAZINEMAGAZINE March 2004 ISSN 1366-0799 FocusFocus onon CommunicationCommunication From your editor It has been a very busy couple of months as Paul SImpson, my son Matthew and I have worked on the ‘new look’ website. Matthew has completed the design so that we can manage the site more easily independently and also so that it is easy for visitors to explore the pages. Thanks to those of you who have emailed us to say that you appreciate the changes and have found lots of new files and information to support you in your work. We now have an email address specifically for contacting us about the website - [email protected] - as we hope to keep the calendar up to date with brief details of courses and meetings. Just email the details of date, organisation, title and venue and we will add it (for free) to the calendar. Call for articles and suggestions for inclusion in future Magazines: Planning for forthcoming Magazines includes: The Teacher of the Deaf in the 21st Century; Deafness and Dyslexia; Creativity; Deaf Education in Europe and Worldwide; British Sign Language Consortium If you have short articles and photographs that will help expand the contents table please contact me and let me know as soon as possible. This doesn’t mean that articles about other topics and activities are not sought! PLEASE share your experiences and achievements with us - many of you are isolated as peris and to share ideas is an important form of personal professional development. The Magazine is a recognised leading vehicle for doing this. -

Private Eric DAVISON Service Number: 684 10Th Battalion (Grimsby Chums) Lincolnshire Regiment Died 1St July 1916 Aged 26

Rank Full NAME Service Number : xxxx 10th Battalion (Grimsby Chums) Lincolnshire Regiment Died 1st July 1916 aged ? Commemorated on Thiepval Memorial Pier and face 1C WW1 Centenary record of an Unknown Soldier Private Eric DAVISON Service Number: 684 10th Battalion (Grimsby Chums) Lincolnshire Regiment Died 1st July 1916 aged 26 Commemorated on Thiepval Memorial Pier and face 1C WW1 Centenary record of an Unknown Soldier Recruitment – 10th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment – The Grimsby Chums Private Eric DAVISON was a member of the Grimsby Chums who were a Pals battalion of Kitchener's Army raised in and around the town of Grimsby in Lincolnshire in 1914. When the battalion was taken over by the British Army it was officially named the 10th (Service) Battalion, The Lincolnshire Regiment. It was the only 'pals battalion' to be called 'chums'. Battle of the Somme The plan was for the British forces to attack on a fourteen mile front after an intense week-long artillery bombardment of the German positions. Over 1.6 million shells were fired, 70 for every one metre of front, the idea being to decimate the German Front Line. Two minutes before zero-hour 19 mines were exploded under the German lines. Whistles sounded and the troops went over the top at 7.30am. They advanced in lines at a slow, steady pace across No Man's Land towards the German front line. Objective 9 – La Boisselle – The Somme - See Fig 1. Attack on La Boisselle Private Eric DAVISON and the 10th Lincolns were assigned Objective 9, an attack on the village of La Boisselle. -

The Russo-Japanese War, Britain's Military Observers, and British

Born Soldiers Who March Under the Rising Sun: The Russo-Japanese War, Britain’s Military Observers, and British Impressions Regarding Japanese Martial Capabilities Prior to the First World War by Liam Caswell Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia December 2017 © Copyright by Liam Caswell, 2017 Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………… ii Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….. iii List of Abbreviations Used……………………………………………………………… iv Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………… v Chapter I Introduction……………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter II “An Evident Manifestation of Sympathy”: The Relationship between the British Press and Japan at War………………………………………………………….. 25 Chapter III “Surely the Lacedaemonians at Thermopylae were Not Braver than these Men”: British Observers and the Character and Ability of the Japanese Soldier…………………………………………………………………………………... 43 Chapter IV “Russia’s Invincible Foe”: Estimations of British Observers Regarding the Performance of the Imperial Japanese Army…………………………………………… 77 Chapter V A Most Impressive Pupil: Captain William Pakenham, R.N., and the Performance of the Imperial Japanese Navy during the War’s Maritime Operations……………………………………………………………………………... 118 Chapter VI Conclusion………………………………………………………………... 162 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………... 170 ii Abstract This thesis explores how Japan’s military triumphs during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-’05 influenced British opinions regarding -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

We Remember Those Members of the Lloyd's Community Who Lost Their

Surname First names Rank We remember those members of the Lloyd’s community who lost their lives in the First World War 1 We remember those who lost their lives in the First World War SurnameIntroduction Today, as we do each year, Lloyd’s is holding a But this book is the story of the Lloyd’s men who fought. Firstby John names Nelson, Remembrance Ceremony in the Underwriting Room, Many joined the County of London Regiment, either the ChairmanRank of Lloyd’s with many thousands of people attending. 5th Battalion (known as the London Rifle Brigade) or the 14th Battalion (known as the London Scottish). By June This book, brilliantly researched by John Hamblin is 1916, when compulsory military service was introduced, another act of remembrance. It is the story of the Lloyd’s 2485 men from Lloyd’s had undertaken military service. men who did not return from the First World War. Tragically, many did not return. This book honours those 214 men. Nine men from Lloyd’s fell in the first day of Like every organisation in Britain, Lloyd’s was deeply affected the battle of the Somme. The list of those who were by World War One. The market’s strong connections with killed contains members of the famous family firms that the Territorial Army led to hundreds of underwriters, dominated Lloyd’s at the outbreak of war – Willis, Poland, brokers, members and staff being mobilised within weeks Tyser, Walsham. of war being declared on 4 August 1914. Many of those who could not take part in actual combat also relinquished their This book is a labour of love by John Hamblin who is well business duties in order to serve the country in other ways. -

In the Shadow of War

(. o tL ý(-ct 5 /ýkOO IN THE SHADOW OF WAR Continuities and Discontinuities in the construction of the identities masculine of British soldiers, 1914 - 1924 i W" NLARGARET MILLNUN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirementsof the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of PHosophy July 2002 ABSTRACT The upheavalsof the cataclysmof the First World War reverberatedthrough every comer of British society, how society was reconstructedafterwards is the subject of enormouscritical debate. This study examineshow masculinitieswere disrupted and. reconstructedduring and after the war. It is a study of British men, previously civilians, who becameservicemen in the First World War. It aims to map the continuitiesand discontinuitiesin the construction of their masculineidentities during war and in its aftermath in the 1920s. Pioneeredby feminist scholarsconcerned with analysingthe historical construction of femininity, the study of gender relations has becomea significant area of historical enquiry. This has resulted in a substantialbody of historical scholarshipon the history of masculinitiesand the increasingvisibility of men as genderedsubjects whose masculinities are lived and imagined. This thesis is informed by, and engageswith, the histories of masculinities. It also draws on recent historical researchon the cultural legacy of the war. The first chapter explores the subjectiveresponses to becominga soldier through an examinationof personalmemoirs; largely unpublishedsources drawn from memoriesand written or recordedby men as narrativesof their wartime experiences.The subject of the secondchapter is shell shock. The outbreak of shell shock among the troops aroused anxietiesabout masculinity. The competing versionsof masculinitieswhich emergedin military and medical discoursesis examined. Returning to individual memoirs,the chapter examineshow men producedtheir own representationsof the shell shockedman contesting other versions. -

New Perspectives Onwest Africa Andworldwar

Journal of African Military History 4 (2020) 5–39 brill.com/jamh New Perspectives on West Africa and World War Two Introduction Oliver Coates University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK [email protected] Abstract Focusing on Anglophone West Africa, particularly Nigeria and the Gold Coast (Ghana), this article analyses the historiography of World War Two, examining recruitment, civil defence, intelligence gathering, combat, demobilisation, and the predicament of ex- servicemen. It argues that we must avoid an overly homogeneous notion of African participation in the war, and that we should instead attempt to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants, as well as differentiating in terms of geography and education, all variables that made a significant difference to wartime labour condi- tions and post-war prospects. It will show how the existing historiography facilitates an appreciation of the role of West Africans in distinct theatres of combat, and exam- ine the role of such sources as African war memoirs, journalism and photography in developing our understanding of Africans in East Africa, South and South-East Asia, and the Middle East. More generally, it will demonstrate how recent scholarship has further complicated our comprehension of the conflict, opening new fields of study such as the interaction of gender and warfare, the role of religion in colonial armed forces, and the transnational experiences of West Africans during the war. The article concludes with a discussion of the historical memory of the war in contemporary West African fiction and documentary film. Keywords World War Two – Africa – West Africa – Asia – warfare – military – military labour – historical memory © oliver coates, 2020 | doi:10.1163/24680966-00401007 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. -

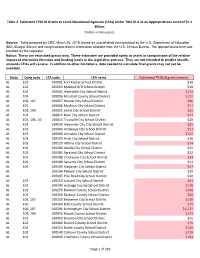

Page 1 of 283 State Cong Code LEA Code LEA Name Estimated FY2018

Table 2. Estimated FY2018 Grants to Local Educational Agencies (LEAs) Under Title IV-A at an Appropriations Level of $1.1 Billion Dollars in thousands Source: Table prepared by CRS, March 26, 2018, based on unpublished data provided by the U.S. Department of Education (ED), Budget Service and congressional district information available from the U.S. Census Bureau. The appropriations level was provided by the requester. Notice: These are estimated grants only. These estimates are provided solely to assist in comparisons of the relative impact of alternative formulas and funding levels in the legislative process. They are not intended to predict specific amounts LEAs will receive. In addition to other limitations, data needed to calculate final grants may not yet be available. State Cong code LEA code LEA name Estimated FY2018 grant amount AL 102 100001 Fort Rucker School District $10 AL 102 100003 Maxwell AFB School District $10 AL 104 100005 Albertville City School District $153 AL 104 100006 Marshall County School District $192 AL 106, 107 100007 Hoover City School District $86 AL 105 100008 Madison City School District $57 AL 103, 106 100011 Leeds City School District $32 AL 104 100012 Boaz City School District $41 AL 103, 106, 107 100013 Trussville City School District $20 AL 103 100030 Alexander City City School District $83 AL 102 100060 Andalusia City School District $51 AL 103 100090 Anniston City School District $122 AL 104 100100 Arab City School District $26 AL 105 100120 Athens City School District $54 AL 104 100180 Attalla -

Wealthy Business Families in Glasgow and Liverpool, 1870-1930 a DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY In Trade: Wealthy Business Families in Glasgow and Liverpool, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Emma Goldsmith EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2017 2 Abstract This dissertation provides an account of the richest people in Glasgow and Liverpool at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. It focuses on those in shipping, trade, and shipbuilding, who had global interests and amassed large fortunes. It examines the transition away from family business as managers took over, family successions altered, office spaces changed, and new business trips took hold. At the same time, the family itself underwent a shift away from endogamy as young people, particularly women, rebelled against the old way of arranging marriages. This dissertation addresses questions about gentrification, suburbanization, and the decline of civic leadership. It challenges the notion that businessmen aspired to become aristocrats. It follows family businessmen through the First World War, which upset their notions of efficiency, businesslike behaviour, and free trade, to the painful interwar years. This group, once proud leaders of Liverpool and Glasgow, assimilated into the national upper-middle class. This dissertation is rooted in the family papers left behind by these families, and follows their experiences of these turbulent and eventful years. 3 Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the advising of Deborah Cohen. Her inexhaustible willingness to comment on my writing and improve my ideas has shaped every part of this dissertation, and I owe her many thanks.