Tort Liability Surrounding Homebuilt, Amateur-Built, and Experimental Aircraft, 60 J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1 Introduction to the Lancair ES Fastbuild

Chapter 1 Introduction to the Lancair ES FastBuild Kit 1.1 Introduction The purpose of this chapter is to familiarize you with the use of this manual, the general philosophy behind its layout, how to set up your shop and what supplies you will need. You should also read the recommended books to familiarize yourself with glassworking if you are a newcomer to fiberglass construction techniques. 1.1 Introduction . 1.1 Always refer to the Glossary on page G.1 for definitions of unfamiliar terms. 1.2 Recommended Reading and Background Information . 1.2 1.3 The Manuals, Blueprints and the ES CD. 1.3 1.3.A Manual Layout. 1.3 1.3.B Blueprints. 1.4 1.3.C The ES CD . 1.4 1.4 Setting up your Shop. 1.5 1.4.A Shop Size . 1.5 1.4.B Temperature Control . 1.5 1.4.C Cutting and Layup Tables . 1.6 1.4.D Making a Useful Jack Stand . 1.7 1.5 Shop Tools and Supplies . 1.8 1.5.A Basic Tools . 1.8 1.5.B Specialized Tools . 1.10 1.5.C Supplies. 1.14 Chapter 1 Page 1.1 REV. 2nd Ed./08-15-06 Introduction to the Lancair ES FastBuild Kit ES Lancair International Inc., Represented by Neico Aviation Inc., Copyright 2008 Redmond, OR 97756 1.2 Recommended Reading and Background Information The following recommended books largely describe aspects of aircraft construction other than working with fiberglass: This manual provides detailed step-by-step instructions for assembling the Lancair ES Kit. -

EAA Webinars Are Supported by EAA Sportair Workshops Are Sponsored By

The Spirit of Homebuilt Aviation I www.eaa.org Vol.2 No.12 I December 2013 A Tale of 10 Tailwinds Jim Clement’s Pride The Maverick LSA Finding a Ride 30 Years of Challengers Flight Control Forces EEAAEXP_Dec13.inddAAEXP_Dec13.indd 1 112/30/132/30/13 99:00:00 AAMM Tower Frequency EAA Tackles the Big Issues By Jack J. Pelton All segments of personal aviation will face FBOs so it can be available to more pilots. High Cost of New Airplanes: Airplane major challenges over the coming years. Making autogas STCs possible was the manufacturing costs are driven by many At EAA we have programs in place to help crucial fi rst step, and now we need to factors including small production runs resolve the biggest problems. We’re not help create a distribution method. and complex FAA certifi cation rules. EAA miracle workers, but by working together is strongly supporting a revision of the we can make a difference. EAA is participating closely with the avia- FAA rules that govern small airplane certi- tion industry and other aviation associa- fi cation. Simplifi cation of those standards Shrinking Pilot Population: This is the No. tions to help identify and certify a lead- can reduce new airplane development 1 issue because when fewer people fl y, free replacement avgas. The key here is costs. If costs can be brought down, the entire aviation activity—including to fi nd the unleaded fuel that works for production rates can increase, creating airports and infrastructure—shrinks and all piston airplane owners with minimum additional savings and lower prices. -

Official EAA Judging Standards Manual

EXPERIMENTAL AIRCRAFT ASSOCIATION O F F I C I A L E A A J U D G I N G S T A N D A R D S M A N U A L June 2017 1 FOREWORD The EAA Official Judging Standards is compiled by the EAA Judging Standards Committee. The EAA Official Judging Standards is the basis of judging at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh and other major fly-ins and provides judges and the exhibitor/competitors in each class the rules and criteria, which are used in evaluating the aircraft. The purpose of the EAA Official Judging Standards is to provide uniformity and continuity of judging standards to all concerned especially the judges, fly-in directors, and participants of all major events across the United States and around the world. These EAA Official Judging Standards are continuously monitored and updated to reflect changes as they evolve in all these fields, and changes may be implemented before they are published. EAA Members are encouraged to submit their comments and recommendations per the procedures outlined in the EAA Judging Policy published at the end of this Forward. We look forward to responding to the comments made by EAA members who would like to improve the Judging Standards. The Judging Standards Committee represents the EAA Board of Directors and President in all aspects related to standards and judging at the annual International EAA AirVenture Fly-In and Convention held annually on Wittman Regional Airport, Oshkosh, Wisconsin. It is the intent that this manual serves as the standard for judging at EAA events. -

EAA Chapter 766 January 2021

PROPWASH EAA Chapter 766 January 2021 The United States Government Task In this Newsletter Force encourages everyone to follow the CDC recommendations of Information 1 self-isolation, physical distancing Chapter 766 Minutes 2,3 and wearing masks. EAA Chapter EAA 766 & AHC Events 4 Airport Newsletter 5 766 will hold virtual meetings in Wright Brothers Banquet 6 place of the in-person monthly EAA Home Builders Event 7 meetings. Michael Jones will FAA FAASTeam Safety 8 facilitate the meetings and will send 10 Tips For Happier 2021 9,10 out emails with directions to the Submissions / Future Meetings 11 members. The meetings will be held the 3rd Monday at 6:30 p.m. Sheboygan County Memorial Airport - KSBM Elevation - 755.2 ft. CTAF/UNICOM - 122.7 Pattern Attitude - 1555.2 ft. Wind Indicator - Yes Runway 4 / 22 (037 / 217 Magnetic) Runway 13 / 31 (132 / 312 Magnetic) Dimensions - 6800 x 100 ft. Dimensions - 5002 x 75 ft. Surface - Grooved Concrete Surface - Asphalt Traffic Pattern - Left Traffic Pattern - Left Airplane Maintenance (920) 467-6151 Mike and Troy After hours (920) 207-9126 (920) 467-8611 Please “like” EAA Chapter 766 Sheboygan Falls WI EAA Chapter 766 Meeting Minutes-Online Membership Meeting Monday 12/21/2020 Opening The December online membership meeting of EAA Chapter 766 was called to order at 6:30 p.m. Monday 12/21/2020. Traditionally, this meeting has been conducted as a year -end social. The online meeting was limited in business scope and was intended more as a virtual social. Present- 11 participants Approval of Agenda-Approved by Majority Approval of Minutes-November minutes were approved by the Board. -

Airman Transition to Experimental Or Unfamiliar Airplanes

U.S. Department Advisory of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration Circular Subject: Airmen Transition to Experimental or Date: 3/30/11 AC No: 90-109 Unfamiliar Airplanes Initiated by: AFS-800 Change: 1. PURPOSE. This advisory circular (AC) provides information and guidance to owners and pilots of experimental airplanes and to flight instructors who teach in these airplanes. This information and guidance contains recommendations for training experience for pilots of experimental airplanes in a variety of groupings based on performance and handling characteristics. This AC does not address the testing of newly built experimental airplanes. The current edition of AC 90-89, Amateur-Built Aircraft and Ultralight Flight Testing Handbook, provides information on such testing. However, if a pilot is planning on participating in a flight- test program in an unfamiliar experimental airplane, this AC should be used to develop the skills and knowledge necessary to safely accomplish the test program using AC 90-89. This AC may also be useful in planning the transition to any unfamiliar fixed-wing airplanes, including type- certificated (TC) airplanes. 2. BACKGROUND. a. Experimental Airplanes. The experimental airplane community is an important part of the civil aviation industry in the United States; some of aviation’s greatest technological achievements were developed by amateur airplane builders. The amateur builder community is foundational to General Aviation (GA) in the United States (U.S.); however, recent trends in experimental airplane accidents have indicated a need for increased effort to ensure the preparation of pilots for the challenges of these airplanes. Historically, experimental airplane flight operations represent a small component of flight hours, but a significant percentage of GA accidents. -

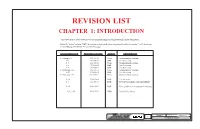

Chapter 1: Introduction

REVISION LIST CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION The following list of revisions will allow you to update the Legacy construction manual chapter listed above. Under the “Action” column, “R&R” directs you to remove and replace the pages affected by the revision. “Add” directs you to insert the pages shows and “R” to remove the pages. PAGE(S) AFFECTED REVISION # & DATE ACTION DESCRIPTION 1-1 through 1-5 0/02-15-02 None Current revision is correct 1-6 1/09-18-02 R&R Text Correction 1-7 0/02-15-02 None Current revision is correct 1-8 1/09-18-02 R&R Text Correction 1-9 1/09-18-02 R&R Text Correction 1-10 through 1-26 0/02-15-02 None Current revision is correct 1-27 1/09-18-02 R&R Text Correction 1-28 through 1-44 0/02-15-02 None Current revision is correct 1-10 2/06-30-04 R&R Text correction. 1-3 3/12-15-04 R&R New table of contents with page numbers. 1-38 4/09-30-06 R&R New guideline for rivet location in rod ends. 1-11, 1-28, 6/08/10/07 R&R Hysol/Jeffco changes Chapter 1 REV. 6/08-10-07 1/09-18-02 1-i1-1 INTRODUCTION Lancair International Inc., Represented by Neico Aviation Inc., Copyright © 2007, Redmond, OR 97756 ASSEMBLY MANUAL FOR THE LANCAIR LEGACY Chapter 1 REV. 0/02-15-02 1-1 INTRODUCTION Lancair International Inc., Represented by Neico Aviation Inc., Copyright © 2000 , Redmond, OR 97756 Chapter 1 REV. -

FAA Safety Briefing

FAA Safety November/December 2012 BRIEG FIN Your source for general aviation news and information Small Airplane Federal Aviation www.faa.gov/news/safety_briefing/ Administration The theme of the Nov/Dec 2012 issue of FAA Safety Briefing is “Small Airplane, Big World.” Articles explore the significance of general aviation on a more global scale and focus on the tools and resources that can help you operate safely beyond our borders. Features SAY ALTITUDE…IN METERS?! U.S. Department Changing Measures for a Changing World .........................................5 of Transportation BYE JAM S WILLIAMS Federal Aviation Administration I N THE KNOW WITH ICAO An Inside Look at the International Civil ISSN: 1057-9648 Aviation Organization ..........................................................................9 FAA Safety Briefing BY KIM MiLLER November/December 2012 Volume 51/Number 6 IsK MY TIC ET GOOD THERE? Raymond H. LaHood Secretary of Transportation Michael Huerta Acting Administrator The Ins and Outs of Overseas Flying ...................................................13 Margaret Gilligan Associate Administrator for Aviation Safety BYE JAM S WILLIAMS John M. Allen Director, Flight Standards Service Dennis Pratte Acting Manager, General Aviation and Commercial Division Susan Parson Editor L ET’S GO IsLAND HOPPING Tom Hoffmann Managing Editor Making Your Caribbean Dreams a Reality .......................................16 James R. Williams Associate Editor / Photo Editor BY TOM HOFFMANN Sabrina Woods Assistant Editor Paul Cianciolo Assistant Editor Will Daniel Muddsimmons Assistant Copy Editor ( DON’T GET) LOST IN TRANSLATION John Mitrione Art Director Mastering the Language of Aviation ................................................. 20 Guy Tom Designer BY SUSAN PARSON Published six times a year, FAA Safety Briefing, formerly FAA Aviation News, promotes aviation safety by discussing current technical, regulatory, and procedural aspects affecting the safe operation and maintenance of aircraft. -

Burt Rutan an EAA Perspective by Jack Cox for Sport Aviation Magazine 2011

BURT RUTAN AN EAA PERSPECTIVE By Jack Cox If thinking outside the box and turning that thinking into successful ventures and prod- ucts is a mark of genius, then Burt Rutan (EAA 26033 Lifetime) has claim many times over to that distinction. No other individual in the history of aviation has designed as many aircraft . radically different aircraft . and had them built and flown. • Burt first came to the attention of EAAers in 1972 when he flew his newly completed VariViggen to Oshkosh. • He came to the attention of the entire world in 1986 when the Voyager completed the first non-stop, non-refueled circumnavigation of planet Earth in an airplane. • And to no oneʼs surprise who knew of his accomplishments over the previous 32 years, Burtʼs SpaceShipOne became the first privately designed and constructed manned vehicle to soar into space, winning the ten million dollar Ansari Prize on Octo- ber 4, 2004. Interspersed between those landmark designs were scores of different, often fantastic- ally innovative new aircraft designs - and even an all-composite automobile, a huge wing to replace conventional sails on the 1998 winner of the Americaʼs Cup sailboat competition, huge composite windmill blades and much, much more. Then . last fall the announcement was made that Burt would retire this month, April of 2011, from Scaled Composites, the company he founded in 1982. Burt will be 68 on June 17 of this year, so he has every right and reason to rest on his laurels, but the an- nouncement still came as a shock to those of us who have followed his career from its beginning. -

FAA Safety Briefing Is the FAA Safety Policy Voice of Non-Commercial General Aviation

FAA Safety November/December 2018 BRIEFING Your source for general aviation news and information Birds of a Different Feather The Experimental Experience p 9 Ride the Lightning p 14 Flying Light! p 22 Federal Aviation faa.gov/news/safety_briefing Administration @FAASafetyBrief FAA Safety Briefing is the FAA safety policy voice of non-commercial general aviation. The November/December 2018 “Birds of a Different Feather” issue of FAA Safety Briefing explores the tremendous diversity of general aviation and encourages you to expand your aviation horizons and appreciate the many ways in which you can “enjoy the ride.” The issue also focuses on the new perspectives and the new skills you’ll need to consider when moving on to a different type of flying. 14 Features 7 Birds of a Different Feather So Many Ways to Reach the Skies by Jennifer Caron 9 The Experimental Experience Blazing a New Trail in a “Special” Place by Tom Hoffmann 9 14 Ride the Lightning Aviation’s Electric Future? by James Williams 18 Teaching the Unknown A Balloon Instructor’s Guide to Flight Training Preparation by Adam Magee 22 Flying Light! Managing Expectations with Light-Sport Aircraft by William E. Dubois Departments 18 1 Jumpseat – an executive policy perspective 2 ATIS – GA news and current events 5 Aeromedical Advisory – a checkup on all things aeromedical 6 Condition Inspection – a look at specific medical conditions 13 Checklist – FAA resources and safety reminders 25 Drone Debrief – drone safety roundup 26 Nuts, Bolts, and Electrons – GA maintenance issues 29 Angle of Attack – GA safety strategies 30 Vertically Speaking – safety issues for rotorcraft pilots 31 Flight Forum – letters from the Safety Briefing mailbag 22 32 Postflight – an editor’s perspective Inside back cover FAA Faces – FAA employee profile RICK DOMINGO Jumpseat EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, FLIGHT STANDARDS SERVICE New Perspectives, New Skills Changes and Challenges It seems very appropriate that my Jumpseat the manager of the legacy Northwest-Mountain and department debut appears in the FAA Safety Central region. -

Goulet Printery Printersof the Simsbury Fly-In Program

WHERE THE DONATIONS GO TABLE OF CONTENTS imsbury Airport is a public use airport yet it receives no WHERE THE DONATIONS GO 1 Slocal, state or federal funding of any kind. Not a single HISTORY OF THE SIMSBURY FLY-IN 1 one of your tax dollars has ever gone to keeping this airport EXHIBITORS/ADVERTISERS 5 open. So, how is the airport funded? From aircraft tiedown BETCHA DIDN’T KNOW 6 fees, subleasing office space and selling fuel; but even those sources are not adequate to cover operational costs. So how PORTER AND CHESTER INSTITUTE 9 do we stay financially viable? The Simsbury Fly-In and Car NOTEWORTHY AIRCRAFT 10 show is the major factor in making ends meet. Whether you SEMINARS 13 buy a t-shirt, make a donation at the gate, eat a burger or THE WHOLE PICTURE 14 volunteer your time, you’re helping preserve a vital transpor- tation link and a tremendous resource for your local commu- YOU’RE BUILDING WHAT?!?! 17 nity. All the money raised here will go towards keeping the THE DIGITAL COCKPIT 21 airport operating. SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 25 None of the Simsbury Flying Club board members SPECIAL THANKS 26 receive compensation of any kind. We do this because we EVENT MAP 29 love aviation, the Simsbury Airport and the freedom of flight. FAMILY OWNED SINCE NEW 31 We hope you get to experience some of that magic at this event today. If you have any questions, just find anyone with EXPERIMENTAL AIRCRAFT ASSOCIATION 35 a bright yellow shirt that CROSSWORD ANSWER KEY 41 says “EVENT STAFF” and SIMSBURY FLY-IN COMMITTEE 42 we’ll be happy to help you. -

EAA Facts / Highlights

The Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) was founded on January 26, 1953 in Milwaukee, Wis., as a local club for those who built and restored their own aircraft. It quickly grew to become a vibrant and growing aviation community that includes all who enjoy flying for recreation and welcomes all aviation enthusiasts to participate. Today, EAA is a non-profit 501(c)(3) corporation (legal name: Experimental Aircraft Association Inc.) that includes 200,000 members in more than 100 countries. EAA’s mission is dedicated to growing participation in aviation. We inspire members to build, fly, restore, volunteer, and outreach to encourage others to pursue their aviation dreams. EAA ignites and nurtures interest by embracing “The Spirit of Aviation” by creating pathways to aviation participation and fulfilling those areas most embraced by aviators. Those include: AirVenture Chapters Publications Advocacy Youth Education Knowledge & Information EAA is governed by a board of directors elected by its membership. That board elects the association’s President, which administers EAA’s full-time staff of approximately 175 employees at its headquarters in Oshkosh, Wis. In addition, EAA has nearly 1,000 local Chapters, which promote local aviation activities in their communities and regions. FAST FACTS Headquarters: EAA Aviation Center, Oshkosh, Wisconsin. CEO/Chairman of the Board: Jack J. Pelton (2012-present) Total international membership: 200,000 History: After EAA’s founding in 1953, its first headquarters was located in the basement of the home of Paul Poberezny (1921-2013), EAA’s President from 1953 until 1989 and father of current chairman Tom Poberezny, who served as EAA President 1989-2010. -

Minnesota Airports Conference April 18–20, 2018 Duluth Entertainment Convention Center Duluth, Minnesota

Minnesota Airports Conference April 18–20, 2018 Duluth Entertainment Convention Center Duluth, Minnesota R S Y E A 1 MARK YOUR CALENDAR! 2019 Minnesota Airports Conference April 24–26, 2019 Willmar Conference Center Willmar, MN 2020 Minnesota Airports Conference April 29–May 1, 2020 Mayo Civic Center Rochester, MN Thank you to our Platinum sponsors! TABLE OF CONTENTS General Conference Information ...................................................... 1 Conference At-a-Glance ................................................................... 2 MCOA Welcome ............................................................................. 3 MCOA Board of Directors ............................................................... 4 MnDOT Aeronautics Overview ....................................................... 5 MnDOT Aeronautics Staff ............................................................... 6 Schedule: Wednesday, April 18 ......................................................... 7 Schedule: Thursday, April 19 ............................................................ 8 Schedule: Friday, April 20 .............................................................. 10 Exhibitors ....................................................................................... 11 Exhibit Hall Map ........................................................................... 12 Exhibitor Contact Information ...................................................... 13 Speaker Bios ..................................................................................