Engagement for Enhancement Institutional Case Studies from a UK Survey Pilot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prospectus Perseverance / Character / Hope Immanuel College Post 16 / Prospectus Immanuel College

Immanuel College Prospectus Perseverance / Character / Hope Immanuel College Post 16 / Prospectus Immanuel College Immanuel College Post 16 was the natural step for me and many of my peers from year 11. We find the support and teaching to be excellent and we are treated more like adults. I enjoy studying the subjects I’m passionate about. “Year 12 Student Opportunities and lessons have made me step outside my comfort zone in year 12. I now have a career goal thanks to the support I’ve received in post 16. ” Current student Welcome to “ Immanuel College Post 16 We are very proud of Immanuel College post 16 and the outstanding achievements of our students. We have had another record year at A-level with a quarter of grades being A/A*. At Immanuel College we offer a broad range of high quality courses to suit every learner ” alongside a rich choice of extracurricular activities that will develop skills and talents. Each year our students gain their first choice Immanuel university places or take up employment opportunities, progressing successfully to their next step. e eg ll Co I joined Immanuel College in year 12 and I’m pleased to say the teaching and results are everything I hoped for. It’s a successful school with a good reputation in the area. “Year 12 Student ” Perseverance / Character / Hope 1 Immanuel College Post 16 / Prospectus Immanuel College Post 16 / Prospectus Immanuel Immanuel e eg ll Co College We are a truly comprehensive school and welcome applications Romans 5:4 from all learners. Our success is the result of our dedicated, caring Perseverance produces character; and supportive teachers, tutors and leaders who work within a strong Christian community. -

Access & Participation Plan 2019-20

York St John University Access & Participation Plan 2019-20 Access & Participation Plan 2019-20 York St John University A history of widening access York St John University has been widening access to higher education since its founding as a Teacher Training College by the Church of England in 1841: “…as the most powerful means of remedying the existing defects in the Education both of the Poor and Middle Classes of Society, to establish a School for the purpose of Training Masters in the Art and Practice of Teaching.” This has underpinned our approach ever since, as can been seen in the development of our latest Strategic Plan. Contents Section 1 Assessment of current performance 2 Section 2 Ambitions and Strategy 7 Section 3 Targets 10 Section 4 Access, success and progression measures 10 Section 5 Investment 19 Section 6 Provision of information to students 19 Appendix Students’ Union submission 20 1 York St John University Access & Participation Plan 2019-20 1. Assessment of current performance Our size and shape York St John University currently has 5,100 APP-countable students (paying Home/EU fees and studying on UG Degree, Foundation Degrees or PGCE courses). Figure 1 shows how this overall student population is broken down into the five underrepresented groups identified by the Office for Students (OfS) and the intersections between those groups: Figure 1 Understanding our student population in terms of underrepresented groups and their intersectionality (as at 1 February 2018) The largest of our underrepresented groups is the POLAR quintiles 1 and 2 metric. POLAR looks at how likely young people are to participate in Higher Education (HE). -

NSS Review Phase One Report

NSS review Phase one report Reference OfS 2021.05 Enquiries to [email protected] Publication date 30 March 2021 Contents Executive summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 Evidence and findings ..................................................................................................................... 3 Recommendations .......................................................................................................................... 6 Background ................................................................................................................................... 7 Governance and funding ................................................................................................................. 8 Concerns about the NSS .............................................................................................................. 8 Terms of reference ........................................................................................................................ 9 Working group .............................................................................................................................. 9 Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 10 Analysis: NSS and degree outcomes ........................................................................................ 19 Discussion of each of the terms -

The Role of Student Satisfaction Data in Quality Assurance and Enhancement: How Providers Use Data to Improve the Student Experience

The Role of Student Satisfaction Data in Quality Assurance and Enhancement: How Providers Use Data to Improve the Student Experience Subscriber Research Series 2015-16 Dr Joanna Williams and George Mindano University of Kent Subscriber Research Series 2015-16 In 2014-15, following a call for expressions of interest open to its subscribers, QAA commissioned six small-scale primary research projects intended to encourage collaboration between providers and promote the formation of communities of practice. This report is one of two on the topic of the role of student satisfaction data in quality assurance and enhancement. It was submitted to QAA by the University of Kent, and written by Dr Joanna Williams and George Mindano. The reports are not QAA documents, so we have respected the authors' approach in terms of style and presentation. We hope that you will read them with interest. Other topics in the series are the transition experiences of entrants to higher education from increasingly diverse prior educational experiences; and an impact study of the guidance documents for higher education providers published by QAA in 2013. For more information, and to read other reports in the series, visit www.qaa.ac.uk/improving-higher-education/research Contents 1 Background ................................................................................................................ 1 2 Methodology .............................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Analytical framework ................................................................................................... -

National Student Survey

National Student Survey Analysis of national results for 2011 Alex Buckley August 2012 Contents Key findings ______________________________________________________________ 3 1. How to use this report ___________________________________________________ 5 1.1 Statistical significance _________________________________________________ 6 2. Overall results _________________________________________________________ 8 2.1 Overall item scores __________________________________________________ 8 2.2 Overall scale scores _________________________________________________ 10 2.3 Relationships between aspects of the student experience ______________________ 11 2.4 Impact of aspects of the student experience on overall satisfaction _______________ 12 3. Student characteristics __________________________________________________ 13 3.1 Differences between age groups ________________________________________ 13 3.2 Differences between genders __________________________________________ 16 3.3 Differences between disability and no known disability ________________________ 18 3.4 Differences between subject clusters ____________________________________ 20 3.5 Differences between student domicile ____________________________________ 23 3.6 Differences between part-time and full-time students _________________________ 25 3.7 Differences between part-time Open University students and other part-time students 27 4. Institutional characteristics _______________________________________________ 29 4.1 Differences between UK nations________________________________________ -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Non-EU International Students in UK Higher Education Institutions: Prosperity, Stagnation and Institutional Hierarchies MATEOS-GONZALEZ, JOSE,LUIS How to cite: MATEOS-GONZALEZ, JOSE,LUIS (2019) Non-EU International Students in UK Higher Education Institutions: Prosperity, Stagnation and Institutional Hierarchies, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13359/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Non-EU International Students in UK Higher Education Institutions: Prosperity, Stagnation and Institutional Hierarchies José Luis Mateos-González Department of Sociology, Durham University A thesis submitted to Durham University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2019 1 To my mum –her unconditional support has made this thesis possible. A mi madre, cuyo apoyo incondicional ha hecho de esta tesis una realidad. To my dad –I will always miss him. -

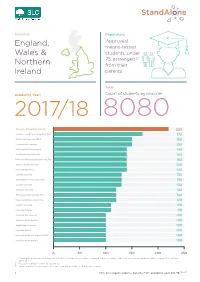

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Post 18 Option Choices Evening – Presentations

Post 18 Option Choices Evening – Presentations Y12 Parents - Please book these presentations on ParentPay. All presentations are at 5.30pm and 6.30pm. Organisation Speaker Presentation Topics Room Apprenticeships CYC Beverley Wills How Apprenticeships Work En1 Studying at Askham Bryan Askham Bryan College Rob Wilson En2 General Information on University of Huddersfield Jane Murphy En3 the University of Huddersfield Studying at Lancaster University Michaela Lowerson Ma2 Lancaster University Leeds Beckett University Rob Rattray The University Application Process Ma3 Student Life/Expectations Newcastle University Sophie Bennett The Unique Student Experience Ma4 in Newcastle Application Process Student Finance Northumbria University Lisa Shannon Choosing a Course HSC Choosing a University Accommodation University of Oxford Dr Dave Leal Interviews/ Admissions RE1 Student Finance Why Choose Higher Education? Sheffield Hallam University Becki McKechnie RE2 Why Choose Sheffield? UCAS process University of Hull Amy Newton Studying at the University of Hull ME Supporting Your Child: Admissions University of Leeds Amy Wilson RE3 Student Finance Accommodation Applying to Higher Education Russell Group Universities University of Sheffield Suzie Murray How to Give a Competitive Edge to your NBM University Application Student Life University of York Lorna Bowling Life at the University of York NBPE University of St Andrews University of St Andrews Kirsty McDonald Studying in Scotland NBS Studying Chemistry York St John University Zack Sizer Studying at York St John NBE Ex All Saints Student at Pembroke College, Oxford. In her final year of studying a 4 year Jess Ellins integrated Masters in Bio-Chemistry. NB6 Starting a PhD at Imperial College in September 2019. The Alcohol Trust Practical advice for parents and students. -

College and University Acceptances

COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY ACCEPTANCES 2016 -2020 UNITED KINGDOM • University of Bristol • High Point University • Aberystwyth University • University of Cardiff • Hofstra University • Arts University Bournemouth • University of Central Lancashire • Ithaca College • Aston University • University of East Anglia • Lesley University • Bath Spa University • University of East London • Long Island University - CW Post • Birkbeck University of London • University of Dundee • Loyola Marymount University • Bornemouth University • University of Edinburgh • Loyola University Chicago • Bristol, UWE • University of Essex • Loyola University Maryland • Brunel University London • University of Exeter • Lynn University • Cardiff University • University of Glasgow • Marist College • City and Guilds of London Art School • University of Gloucestershire • McGill University • City University of London • University of Greenwich • Miami University • Durham University • University of Kent • Michigan State University • Goldsmiths, University of London • University of Lancaster • Missouri Western State University • Greenwich School of Management • University of Leeds • New York Institute of Technology • Keele University • University of Lincoln • New York University • King’s College London • University of Liverpool • Northeastern University • Imperial College London • University of Loughborough • Oxford College of Emory University • Imperial College London - Faculty of Medicine • University of Manchester • Pennsylvania State University • International School for Screen -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1 Report introduction................................................................................................................................................................... 1 2 The Erasmus Mundus project (2012-2015) ............................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Handbook conceptual approach ...................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Open source handbook ................................................................................................................................................... 2 3 The Social and Solidarity Economy Conference ........................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 Conference theme ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Conference aim and objectives ....................................................................................................................................... 3 3.3 Conference methodology ................................................................................................................................................ 4 3.4 Project and conference acknowledgements (in alphabetical order by surname) ........................................................... 4 3.5 -

Student Satisfaction, League Tables and University Applications: Evidence from Britain

Stephen Gibbons, Eric Neumayer, Richard Perkins Student satisfaction, league tables and university applications: evidence from Britain Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Gibbons, Stephen, Neumayer, Eric and Perkins, Richard (2015) Student satisfaction, league tables and university applications: evidence from Britain. Economics of Education Review. ISSN 0272-7757 DOI: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.07.002 © 2015 Elsevier Ltd. This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/62875/ Available in LSE Research Online: July 2015 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Student satisfaction, league tables and university applications: Evidence from Britain Stephen Gibbons*† Eric Neumayer* Richard Perkins* June 2015 *Department of Geography and Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) † Spatial Economics Research Centre and Centre for Economic Performance, LSE Abstract We investigate the impact of information about student satisfaction on university choice, using data from the UK’s National Student Survey (NSS) and on applications to undergraduate degrees. -

Mental Wellbeing – a Whole System Approach

UK HEALTHY UNIVERSITIES NETWORK YORK ST JOHN UNIVERSITY WEDNESDAY 24 MAY 2017 NOTES FROM MEETING & REPORT OF THEMED SESSION/WORKSHOP MENTAL WELLBEING – A WHOLE SYSTEM APPROACH CONTENTS Welcome ................................................................................................................................. 1 Network Update ...................................................................................................................... 1 Networking, Sharing of Practice and Peer Support [Round Table Discussions] ............................ 2 Spotlight: Key Updates ............................................................................................................. 2 Themed Session: Mental Wellbeing – A Whole System Approach ............................................. 3 Next Meeting ........................................................................................................................... 5 Appendix 1: Attendance .......................................................................................................... 6 WELCOME Emma Wilkins, Executive Director of Student and Staff Services, welcomed everyone to York St John University and the Network Meeting. She went on to give an overview of the University’s history and development and its commitment to widening participation in higher education. Emma talked about the University’s internal structures that ensured wellbeing and how its commitment to being a Healthy University was embedded into the institution and its associated activities were