4507 18 Painting Is My Everything Large Print

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inde « Company Period »

INDE « COMPANY PERIOD » VENDREDI 15 AVRIL 2016 À 14H DROUOT RICHELIEU, SALLE 2 9, RUE DROUOT ‑ 75009 PARIS EXPERTS MARIE-CHRISTINE DAVID Avec les collaborations de Suzanne Babey et Azadeh Samii Tél. : + 33 (0) 1 45 62 27 76 [email protected] CONTACT ÉTUDE Marie‑Hélène Corre ‑ Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 06 06 08 ‑ [email protected] EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES A L’HÔTEL DROUOT Jeudi 14 avril de 11h à 18h Vendredi 15 avril de 11h à 12h CATALOGUE ET VENTE SUR INTERNET www.AuctionArtParis.com 9, rue de Duras ‑ 75008 Paris | tél. : +33 (0)1 40 06 06 08 | fax : +33 (0)1 42 66 14 92 SVV agrément N° 2008‑650 ‑ www.AuctionArtParis.com ‑ [email protected] Rémy Le Fur & Olivier Valmier commissaires‑priseurs habilités 1 2 INDE « COMPANY PERIOD » AuctionArt a le plaisir de proposer aux enchères un rare ensemble de portraits de princes indiens dits «Company Period», réuni par un amateur et passionné de voyages, dés le début des années soixante‑dix, au cours d’une trentaine de voyages en Inde parcourant fiévreusement les moindres recoins du Rajasthan. Ce collectionneur a orienté son goût non pas vers les miniatures indiennes plus anciennes mais vers ces portraits de l’époque du RAJ (1860‑ 1947), correspondant à l’occupation de l’Inde par les anglais. Ceux‑ci privèrent les Maharajas et autres princes de toutes prérogatives dans la gestion de leurs états et leur donnèrent le goût des REGALIA : trônes (voir l’ensemble de projets de mobilier en argent réalisé à Bénarès), flattant leur passion pour les bijoux et leur octroyant comme « hochets » des décorations telle que l’Ordre de l’Etoile de l’Inde. -

Living Traditions Tribal and Folk Paintings of India

Figure 1.1 Madhubani painting, Bihar Source: CCRT Archives, New Delhi LIVING TRADITIONS Tribal and Folk Paintings of India RESO RAL UR U CE LT S U A C N D R O T R F A E I N R T I N N G E C lk aL—f z rd lzksr ,oa izf’k{k.k dsUn Centre for Cultural Resources and Training Ministry of Culture, Government of India New Delhi AL RESOUR UR CE LT S U A C N D R O T R F A E I N R T I N N G E C lk aL—f z rd lzksr ,oa izf’k{k.k dsUn Centre for Cultural Resources and Training Ministry of Culture, Government of India New Delhi Published 2017 by Director Centre for Cultural Resources and Training 15A, Sector 7, Dwarka, New Delhi 110075 INDIA Phone : +91 11 25309300 Fax : +91 11 25088637 Website : http://www.ccrtindia.gov.in Email : [email protected] © 2017 CENTRE FOR CULTURAL RESOURCES AND TRAINING Front Cover: Pithora Painting (detail) by Rathwas of Gujarat Artist unknown Design, processed and printed at Archana Advertising Pvt. Ltd. www.archanapress.com All Rights Reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Director, CCRT. Photo Credits Most of the photographs used in this publication are from CCRT Archives. We also thank National Museum, New Delhi; National Handicrafts & Handlooms Museum (Crafts Museum), New Delhi; North Zone Cultural Centre (NZCC), Patiala; South Central Zone Cultural Centre (SCZCC), Nagpur; Craft Revival Trust, New Delhi and Sanskriti Museum, New Delhi for lending valuable resources. -

Artistes Indiens Dhruvi Acharya =Ratnadeep Adivrekar = Iloosh

Artistes indiens Dhruvi Acharya =Ratnadeep Adivrekar = Iloosh Ahluwalia ==V Anamika =Sekar Ayyanthole =Bhuri Bai =Lado Bai==Ramkinkar Baij =Uma Bardhan =Atasi Barua =Madhuri Bhaduri =Bikash Bhattacharjee =Manjit Bawa =Nandalal Bose =Vasundhara Tewari Broota =Maya Burman =Nek Chand = Shanthi Chandrasekar = = Kailash Chandra ==Manimala Chitrakar ==Jogen Chowdhury =Anju Chaudhuri =Bijan Choudhury =Daku= Dhiraj Choudhury =Prafulla Dahanukar = = Sunil Das =Kurchi Dasgupta = Jahar Dasgupta=M R D Dattan =Bharti Dayal ==Kanu Desai =Baua Devi = Pratima Devi ==Manishi Dey =Mukul Chandra Dey == Atul Dodiya ==Shashikant Dhotre ==Gurpreet Singh Dhuri = =Anita Dube =Anil Kumar Dutta Vasudeo S. Gaitonde =Amrita Sher-Gil ==Kalipada Ghoshal = =Sheela Gowda == Aman Singh Gulati ==Manav Gupta =Shilpa Gupta ==Neeraj Gupta =Satish Gujral =M.F. Husain ==Norman Douglas Hutchinson =S. Jithesh ==Anish Kapoor = Reena Saini Kallat==Renuka Kesaramadu = V Wajid Khan = =Bhupen Khakkar= Latika Katt = = Abdul Kadar Khatri =Mohammed Yusuf Khatri =Mohammed Bilal Khatri = Bharti Kher = Paris Mohan Kumar ==Srimati Lal =Lalitha Lajmi =Ananta Mandal =Paresh Maity = Nalini Malani =Maniam =Ravi Mandlik =Kailash Chandra Meher = Anjolie Ela Menon =Divya Mehra =Rooma Mehra =Samir Mondal ==Rabin Mondal =Benode Behari Mukherjee =Balan Nambiar =Kota Neelima =Badri Narayan Gogi Saroj Pal = Aditya Pande =Baiju Parthan=Jayant Parikh = Gieve Patel ==Rupesh Patric =Sudarsan Pattnaik = M. D. Parashar ==Ketaki Pimpalkhare ==B. Prabha = Pranava Prakash =Gargi Raina = Anil CS Rao ==S. Rajam = Devajyoti Ray =S.H. Raza ==Jamini Roy =Piraji Sagara == Mohan Samant =Somalal Shah =Suvigya Sharma = Arpita Singh = =S. G. Thakur Singh =Dayanita Singh =Francis Newton Souza =ivan Sundaram == Ram Chandra Shukla =Karuna Sukka =Tara Sabharwal ==Silpi ==K.G. Subramanyan =Surekha = Bholekar Srihari == Y.G. Srimati ==Surekha = =Gaganendranath Tagore=Thukral & Tagra = Jaya Thyagarajan = Hema Upadhyay=Geeta Vadhera ==Raja Ravi Varma =Rukmini Varma =Zen Vartan = =Vinita Vasu = Durga Bai Vyom =John Wilkins =Yantr . -

औपबंविक सूची Subject - Social Scince Niyojn Years - 2019-20 Address Matric Inter Graduation Traning Tet /Ctet Applicatio Applicants Mother Father Cetet / Total

कार्ाालर् प्रखंड विकास पदाविकारी गगरी I प्रखंड विर्ोजि इकाई गोगरी औपबंविक सूची SUBJECT - SOCIAL SCINCE NIYOJN YEARS - 2019-20 ADDRESS MATRIC INTER GRADUATION TRANING TET /CTET APPLICATIO APPLICANTS MOTHER FATHER CETET / TOTAL SL NO DOB PH MEDHA % TET % REMARS TET N NO NAME NAME NAME ROY OBTAIN OBTAIN OBTAIN OBTAIN BETET OBTAIN MEDHA % E GRAM DIST FULL MARKS % FULL MARKS % FULL MARKS % FULL MARKS % FULL MARMS P YEARS ROLL NO WETEJ CATEGE SUBJECT GENDER MARKS MARKS MARKS NAM MARKS MARKS YEAR YEAR YEAR YEAR BORD BORD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 KALPNA AKHILESH 1 3432 RENU DEVI F 18.11.1994 BIRPUR BEGUSARAI N 2009 500 381 76.20 2011 500 394 78.80 2014 1500 941 62.73 LIMGAYAS2015 UNIVERSITY FARIDABAD1500 1267 84.47 75.55 BETET 145 2018 2602175536 108 74.48 4 79.55 SST KUMARI SINGH EWS NEELAM FUL KUMARI SUKH SAGAR 2 3733 F 13/06/1995 MAHISHI SAMASTIPUR 2011 500 403 80.60 2013 500 398 79.60 2016 1500 1042 69.47 2019 LNMU DARBHANGA 1300 1042 80.15 77.46 CETET 150 2019 106068788 97 64.67 2 79.46 BC SST KUMARI DEVI MAHTO ARUN JAYPARKASH 3 1847 ASHWINI SIMA DEVI KUMAR F 15.2.1995 KHAGARIA N 2009 500 401 80.20 2011 500 329 65.80 2015 1500 1058 70.53 2019 T.M.B.U 1300 1069 82.23 74.69 CETET 150 2019 201010355 84 56.00 2 76.69 SST NAGAR EBC THAKUR ARCHNA AMBIKA RAMGOPAL 4 803 F 16/10/1994 KHAGARIA KHAGARIA N 2009 500 372 74.40 2011 500 361 72.20 2015 800 589 73.63 2019 MU BODH GAYA 1300 1011 77.77 74.50 CETET 150 2019 107085387 83 55.33 2 76.50 BC SST BHARTI DEVI MAHTO -

Education-Packet-Web.Pdf

1 Detail of Japani Shyam, Jungle Scene, 2011, acrylic on canvas, © 2015, Courtesy of BINDU modern Gallery, Photo credit: Sneha Ganguly 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS: INTRODUCTION 4 MAP OF INDIA 5 FOUR INDIGENOUS TRADITIONS IN INDIA 6 GLOSSARY 12 ARTWORK MEDIUMS 14 SELECTED ARTISTS 17 SUGGESTED PROGRAMMING 26 EDUCATIONAL REFERENCE MATERIALS 30 MERCHANDISE LIST 32 ARTIST WORKSHOPS 34 SPEAKER LIST 36 COVER, Detail of Jamuna Devi, Raja Salhesh with his two brothers and three flower maidens, c. 2000, natural dyes on paper, © 2015, Courtesy of BINDU modern Gallery, Photo credit: Sneha Ganguly 3 EXHIBITION OVERVIEW Many Visions, Many Versions: Art from Indigenous Communities in India is the first comprehensive exhibition in the United States to present contemporary artists from four major indigenous artistic traditions in India. The exhibition includes art from the Gond and Warli communities of central India, the Mithila region of Bihar, and the narrative scroll painters of West Bengal. Featuring 47 exceptional paintings by 24 celebrated artists, including Jangarh Singh Shyam, Ram Singh Urveti, Bhajju Shyam, Jivya Soma Mashe, Baua Devi, Sita Devi, Montu Chitrakar, and Swarna Chitrakar, among others, the exhibition reflects diverse aesthetics that remain deeply rooted in traditional culture, yet vitally responsive to the world at large. The exhibition is divided into four broad categories:Myth and Cosmology, Nature Real and Imagined, Village Life, and Contemporary Explorations. Myth and Cosmology illustrates the rich imagery and diverse pictorial languages used by artists in each group to express the continuing prominence and power of myths, symbols, icons, spiritual traditions, and religious beliefs that are often an amalgam of both Hindu and indigenous worldviews. -

REGISTER PART-A.Xlsx

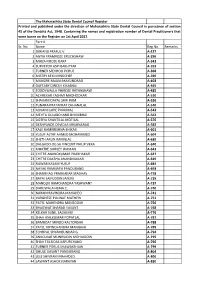

The Maharashtra State Dental Council Register Printed and published under the direction of Maharashtra State Dental Council in pursuance of section 45 of the Dentsits Act, 1948. Containing the names and registration number of Dental Practitioners that were borne on the Register on 1st April 2017. Part-A Sr. No. Name Reg.No. Remarks 1 DIWANJI PRAFUL V. A-227 2 ANTIA FRAMROZE ERUCHSHAW A-296 3 MIRZA FIROZE DARA A-343 4 SURVEYOR ASPI BAKHTYAR A-352 5 TURNER MEHROO PORUS A-368 6 MISTRY KEKI MINOCHER A-396 7 MUNGRE RAJANI MAKUNDRAO A-403 8 DAFTARY DINESH KIKABHAI A-465 9 TODDYWALLA PHIROZE RATANSHAW A-485 10 ACHREKAR YASHMI MADHOOKAR A-510 11 SHAHANI DAYAL SHRI RAM A-526 12 TUNARA PRATAPRAY CHHANALAL A-540 13 ADVANI GOPE PARUMAL A-543 14 MEHTA GULABCHAND BHMJIBHAI A-562 15 DOTIYA SHANTILAL MOTILAL A-576 16 DESHPANDE DEVIDAS KRISHNARAO A-582 17 KALE RAMKRISHNA BHIKAJI A-601 18 YUSUF ALTAF AHMED MOHAMMED A-604 19 SHETH ARUN RAMNLAL A-639 20 DALGADO-DE-SA VINCENT PHILIP VERA A-640 21 MHATRE SHIRLEY WAMAN A-642 22 CHITRE ANANDKUMAR PRABHAKAR A-647 23 CHITRE DAKSHA ANANDKUMAR A-649 24 NAWAB KASAM YUSUF A-684 25 NAYAK RAMNATH PANDURANG A-693 26 SHANBHAG PRABHAKAR MADHAV A-718 27 BAPAI SAIFUDDIN JAFERJI A-729 28 MANDLIK RAMCHANDRA YASHWANT A-737 29 DARUWALA HEMA C. A-740 30 NARAIN RAVINDRA MAHADEO A-741 31 VARGHESE PULINAT MATHEW A-751 32 PATEL MAHENDRA MANSOOKH A-756 33 BHAGWAT SHARAD VASANT A-768 34 KELKAR SUNIL SADASHIV A-776 35 SHAH ANILKUMAR POPATLAL A-787 36 BAMBOAT MINOO RALTONSHA A-788 37 PATEL VIPINCHANDRA MANIBHAI A-789 38 ECHHPAL SHYAMSUNDAR G. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 00120013 DADY FRED

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 00120013 DADY FRED POONAWALA U22219MH2004PLC015589 COMART LITHOGRAPHERS LIMITED 00120013 DADY FRED POONAWALA U93090MH2006PTC164558 COMART ONE PRE-MEDIA PRIVATE 00120013 DADY FRED POONAWALA U74999MH2007PTC167875 IDEAL ART PRIVATE LIMITED 00120013 DADY FRED POONAWALA U74900MH2007PTC174952 ERGO INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED 00120022 LAXMI MANGHRANI U25209RJ2006PTC022446 SHRI GANESH LAXMI POLYMERS 00120041 ISSARDAS MANOHAR TALREJA U15400MH2008PTC187991 MASALA CHAI & FOODS PRIVATE 00120045 CHANDRESH KANAIYALAL POPAT U31400MH1993PLC074343 HORIZON INDIA BATTERIES 00120045 CHANDRESH KANAIYALAL POPAT U67190MH2007PTC171888 SOHUM BROKING PRIVATE LIMITED 00120045 CHANDRESH KANAIYALAL POPAT U45201MH2007PTC176052 PRABHAT INFRASTRUCTRUE 00120046 DAS RANTU U22219AS1993PTC004018 FRONTIER PUBLICATIONS PRIVATE 00120046 DAS RANTU U92132AS2005PTC008386 AM TELEVISION PRIVATE LIMITED 00120046 DAS RANTU U51909AS2000PLC006091 PEE GEE INDIA LIMITED 00120046 DAS RANTU U70101AS2006PTC008213 SARS ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 00120063 MANCHANDA VINEET U45201DL2006PLC147035 GLAZE PROMOTERS LIMITED 00120067 ABHINAV JAIN U28129DL1998PTC095531 C F C PRODUCTS PRIVATE LIMITED 00120083 DAS SMRITALINA U70101AS2006PTC008213 SARS ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 00120089 ATUL KUMAR CHUG U74210DL1988PLC030901 GLOBAL DRILLING FLUIDS AND 00120124 HAWARE SURESH KASHINATH U92199AP2001PLC036387 MOHAN ENTERTAINMENT 00120124 HAWARE SURESH KASHINATH U70100MH1996PTC096092 HAWARE ENGINEERS AND 00120124 HAWARE SURESH KASHINATH U92199MH2001PLC132198 MOHAN AND HAWARE 00120124 -

International Reception of Mithila Paintings and Heroization

International Reception of Mithila Painting and Heroization Constructing Women (Painters) Figures in Yves Véquaud’s Writings Hélène Fleury, University of Paris-Saclay / Center for South Asian Studies (CEIAS) Exhibition Magiciens de la terre, 1989, catalog Les Magiciens de la terre. Baua Devi : Snake Goddesses Mithila or Madhubani Painting Ritual and art forms practiced in northern Bihar and Nepalese Teraï by women of different castes, derived from wall paintings made during celebrations and rites. Home of Kalpna Singh, Madhubani, Representation of Krishna on a hut,Dusadh Figure of Naina-jogin. Wall Painting Detail, 2002. Toli, Jitwarpur, 2002. Ganga Devi, Crafts Museum, New-Delhi, 1989 (In J.Jain, Ganga Devi, 1997) Changing Mithila Painting Shift from a ritual visual practice to an individual creative expression: recognition of individual identity and creativity of the artists. For long, an essentialized conception focusing on authenticity, anonymity and timelessness obscured these shifts. Woman painter on a gandhian desk, Jitwarpur, Publication by a man-painter Rhambaros Jha, of an January 2002 album composed of illustrations inspired by the aquatic world, 2011 1. A brief account of the International Reception of Mithila Painting 2. Yves Véquaud’s cultural network between France and India 3. Yves Véquaud: juxtaposing counter-cultural Bohemia and Maithil village communitarian utopia a. Indian enchantment through the prism of counter-culture b. Yves Véquaud and Bohemia: the invention of an artistic aristocracy? c. The Maithil village as communitarian utopia 4. Constructing Women Painters Figures 1. A brief account of the International Reception of Mithila Painting 2. Yves Véquaud’s cultural network between France and India 3. -

Jagdish Nandan College, Madhubani Degree I Arts Session: 2018-19

Jagdish Nandan College, Madhubani Degree I Arts Session: 2018-19 Class SL NO Roll No Stream DOB NAME FATHER'S NAME MOTHER'S NAME SIGNATURE 1 2 ARTS 16-Jul-00 SHUBHAM KUMAR SINGH RAMBIR SINGH CHANDRAKALA DEVI 2 3 ARTS 20-Feb-00 PRITI KUMARI LALAN PRASAD YADAV ASHA DEVI 3 4 ARTS 06-Mar-98 ANJLI KUMARI RAJESH MAHTO RAKHI DEVI 4 5 ARTS 04-Mar-01 SAWAN KUMAR MISHRA SHAMBHU NATH MISHRA ANJU MISHRA 5 6 ARTS 25-Apr-01 MD IRFAN MD YASIN 6 7 ARTS 10-Apr-01 DILEEP KUMAR YADAV YUGUT LAL YADAV NIRO DEVI 7 8 ARTS 12-Mar-00 MD CHHOTE HUSSAIN MD KASIM RASHIDA KHATUN 8 9 ARTS 06-Feb-01 SUJIT YADAV RAM NARAYAN YADAV SHILA DEVI 9 10 ARTS 02-Jan-00 RUPESH KUMAR SHRINARAYAN SAHU ANJU DEVI 10 11 ARTS 06-Jun-99 ANIKET CHAURASIA GANGA PRASAD PARMILA DEVI 11 12 ARTS 02-Dec-99 MD ASHAIN MD EKBAL PINKY KHATOON 12 14 ARTS 10-Aug-96 MD LAL GULAB MD BASHIR NAJBUL KHATOON 13 15 ARTS 08-May-99 SUSHIL KUMAR NARESH PASWAN 14 16 ARTS 07-Aug-00 BRAHAMDEO YADAV RAMCHHATARY YADAV KRISHNA DEVI 15 17 ARTS 05-Jul-01 SACHIN KUMAR MAHTO SHANKAR MAHTO VINA DEVI 16 18 ARTS 12-Oct-00 RAHUL KUMAR HALKHORI MAHTO RINKY DEVI 17 19 ARTS 10-Mar-99 GHANSHYAM MANDAL BUDHESHWAR MANDAL MUNNI DEVI 18 20 ARTS 16-Feb-98 BIKRAM KAMAT KAMAL KAMAT KAMANI DEVI 19 22 ARTS 03-Jan-01 RAKESH RAM MOHAN RAM CHANDRAKALA DEVI 20 23 ARTS 03-Jul-00 DEEPAK KUMAR THAKUR DILEEP THAKUR SANEETA DEVI 21 24 ARTS 10-Dec-01 ARPIT KUMAR THAKUR RAM PRAVESH THAKUR SUNITA DEVI 22 25 ARTS 23-Feb-00 MD SAMIM MD NAJIM HASRATUN BEGAM 23 26 ARTS 02-Mar-98 PRABESH KUMAR MANDAL LAKSHMAN MANDAL SITA DEVI 24 27 ARTS 20-Feb-01 GANESH -

List of Certification Fees

# LIST OF STUDENTS ELIGIBLE FOR THE CFPCM CERTIFICATION PROGRAM [INCLUDING AFP CERTIFICANTS VIZ. PATHWAY CANDIDATE'S] Registration FPSB India @ Examination(s) S.No. Name of Candidate City Date No. Passed 1 04-Jan-12 59519 Manoranjan Kumar Deoghar NIL 2 04-Jan-12 60965 Sulagna Roy Pune NIL 3 04-Jan-12 61154 Vaibhav Gupta Indore NIL 4 06-Jan-12 61470 Abhilasha Thakur Delhi NIL 5 06-Jan-12 61500 Abhishek Tonde Mumbai NIL 6 06-Jan-12 61423 Abirami Iyer Nagpur NIL 7 06-Jan-12 61160 Ankit Garg New Delhi NIL 8 06-Jan-12 60822 Arpit Mehta Rajkot E1, E2 9 06-Jan-12 61506 Ashish Apte Thane NIL 10 06-Jan-12 61484 Ashoke Mazumder Kolkata NIL 11 06-Jan-12 61357 Avani Shah Delhi E3 12 06-Jan-12 61330 Dinesh Singal Faridabad NIL 13 06-Jan-12 61437 Garima Jhawar Mumbai NIL 14 06-Jan-12 61172 Gaurav Bhardwaj Delhi NIL 15 06-Jan-12 61162 Himanshu Goel Delhi NIL 16 06-Jan-12 56559 Himanshu Puri Delhi NIL 17 06-Jan-12 61216 Ishwar Kanodia Mumbai E1 18 06-Jan-12 61358 Jinesh Shah Mumbai NIL 19 06-Jan-12 61414 Karthik Ramachandran Bengaluru NIL 20 06-Jan-12 61503 Kshitij Kaji Mumbai NIL 21 06-Jan-12 61110 Manu Kakkar Delhi NIL 22 06-Jan-12 61228 Payal Saxena Delhi E1, E2, E3 23 06-Jan-12 61508 Pranil Kamble Thane NIL 24 06-Jan-12 61501 Priyul Shah Mumbai E1, E2, E3, E4 25 06-Jan-12 61466 Prosid Adhikary Kolkata NIL 26 06-Jan-12 61471 Radhika Saraogi Kolkata NIL 27 06-Jan-12 61217 Riddhi Chauhan Mumbai NIL 28 06-Jan-12 61241 Sakshi Wig New Delhi NIL 29 06-Jan-12 61226 Shri Prakash Mishra Delhi NIL 30 06-Jan-12 61322 Shweta Someskar Mumbai NIL 31 06-Jan-12 61502 -

Madhubani Painting—Vibrant Folk Art of Mithila

Art and Design Review, 2020, 8, 61-78 https://www.scirp.org/journal/adr ISSN Online: 2332-2004 ISSN Print: 2332-1997 Madhubani Painting—Vibrant Folk Art of Mithila Soma Ghosh Librarian and Media Officer, Salar Jung Museum, Ministry of Culture, Government of India, Hyderabad, India How to cite this paper: Ghosh, S. (2020). Abstract Madhubani Painting—Vibrant Folk Art of Mithila. Art and Design Review, 8, 61-78. This article traces the historical journey of a unique art-form, that of the https://doi.org/10.4236/adr.2020.82005 painting of walls, floor-spaces and on the medium of paper, of Madhubani painting, referring to the place from where it became famous from the region Received: March 12, 2020 of Mithila in North Bihar. The land of its origin being India, the social and Accepted: April 17, 2020 Published: April 20, 2020 cultural context is also explored. The article aims to document the main art- ists in the field, who have given their lives in preserving this form of painting Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and and been applauded by the Government of India for their efforts. The paint- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. ing style has ancient origins and it has caught the eye of both Indians and for- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International eign art enthusiasts. The different sources from which the colours are derived License (CC BY 4.0). for use have also been noted. Now the art-form finds expression in walls of http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ public places like railway stations, in addition to traditional spaces and during Open Access social events. -

S-68-20180809.Pdf

WIDOW PENSIONER AC-52(TUGHLAKABAD) 2090 CASES S NO Name55 H_Name Address Contact No 1 CHANDA BIBI NISHAR AHMED RZ-235/17,TUGHALAKA BAD VISTAR ND 7838076770 2 URMILA RAJENDER KUMAR H.NO.473/B,JATAV MOHALLA TUGLAKABAD VILL ND 9654422201 3 bimlesh kumari PREM SINGH H.NO.-452 JATAV MOHALLA TUGLAKABAD VILL.ND 9868797316 4 KAMLESH KHEM CHAND RZ-245,G.NO-19,TUGHALAKA BAD VISTAR ND 9811447749 5 FARIDA BEGUM NISHAD KHAN RZ-252A/19,GALI NO-19,TUGHALAKA BAD ND 6 JALISA KHATOON MOHD. ZEERA 15/16,CHURIYA MOH. VILL. TUGHLAKABAD,ND 7 OM WATI GYAN CHAND H-98,LAL KUAN,TUGHLAKA BAD,ND 9958116833 8 VIDYA DEVI NAHAR SINGH B-71-B,LAL KUAN,TUGHLAKA BAD,ND 9650980755 9 LAXMI HANS RAVI HANS D-26,CHUNGI-3,LAL KUAN,TUGHLAKA BAD,ND 9971405530 10 SANTOSH MADAN LAL F-60,PANCH MUKHI MANDIR,TUGHLAKA BAD,ND 9910249532 11 BHURI DEVI RATAN LAL F-43,PANCHMUKHI MANDIR,TUGHLAKA BAD,ND 9871652983 12 NUSRAT IMTIYAZ AHMED RZ 519,GALI NO 24,TUGLAKABAD EXTN. 13 RAFAT KHAN MAJID KHAN 2078/27,GALI NO.27 TUGLAKABAD EXTN. 9654714876 14 KAILASH SOM NATH RZ-9/62/12, TUGHLAKABAD, NEW DELHI-19 15 KAMLSESH LAL CHAND H NORZ 32 G 19,TUGLKABAD 16 TAMESHWARI OMKAR SINGH F-67,LAL KOUN TUGLKABAD 17 SANTOSH PYARA SINGH H NO 41,TUGLKABAD 18 NEETU SHARMA HANS RAJ SHARMA H NO G/7/99, G F TUGLKABAD 19 CHAMAN KISHAN SINGH B-81,BLK C TUGLAKABAD 20 USHA SHYAM KHANDELWAL RZ-119 GALI-3 SE TUGLAKABAD EXTN.