A. Name of Multiple Property Listing B. Associated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lundberg Bakery HABS No. TX-3267 1006 Congress Avenue Austin

Lundberg Bakery HABS No. TX-3267 1006 Congress Avenue m Austin Travis County Texas 11 A Q C PHOTOGRAPHS HISTORICAL AM) DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 2021*3 >S "U-K.2Jn-A\JST, \°i- HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY LUNDBERG BAKERY RABS NO. TX-3267 Location: 1006 Congress Avenue, Austin, Travis County, Texas, USGS Austin East Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: li+.621080.331+9i+10. Present Owner: State of Texas Texas Highway Department 11th and Brazos Streets Austin, Texas Present Occupant: Vacant. Significance: The Lundberg Bakery is an important commercial and historical landmark in Austin. Built in 1875-76, it first housed the successful bakery business of Charles Lundberg, and continued to be used as a bakery until 1937» Located within one block of both the Texas State Capitol and the Governor's Mansion, the restored Victorian structure makes a significant visual contribution to the Capitol Area. PART I: HISTORICAL INFORMATION A.' Physical History: 1. Date of erection: 1875-1876. 2. Architect: Unknown. 3. Original and subsequent owners: The following is an incomplete chain of title to the land on which the structure stands. Reference is to the Clerk's Office of the County of Travis, Texas. iQfh Deed December 17, l8T^, recorded December 19, l&lh in Volume 28, pages 107-108. Ernst Raven and wife to Charles Lundberg. North half of lot 2 in block 12U. 1909 Affidavit April 20, 1909, recorded April 23, 1909, in Volume 226, page h&5* Relates that Charles Lundberg died intestate on February 7, 1895. -

Au Stin, Texas

A UN1ONN RAI LROAD S T A TION FOR AU STIN, TEXAS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER IN ARCHITECTURE at the Massa- chusette Institute of Technology, 1949 by Robert Bradford Newman B.A., University of Texas, 1938 M.A., University of Texas, 1939 2,,fptexR 19i49 William Wilson Wurster, Dean School of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts Dear Sir: In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Architecture, I respect- fully submit this report entitled, "A UNION RAILROAD STATION FOR AUSTIN, TEXAS". Yours vergy truly, Robert B. Newman Cambridge, Massachusetts 2 September 19T9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Austin - The City 3 Railroads in Austin, 1871 to Present 5 Some Proposed Solutions to the Railroad Problem 10 Specific Proposals of the Present Study 12 Program for Union Railroad Station 17 Bibliography 23 I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to the members of the staff of the School of Architecture and Planning of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for their encouragement and helpful criticism in the completion of this study. Information regarding the present operations of the Missouri Pacific, Missouri Kansas and Texas, and Southern Pacific Railroads was furnished by officials of these lines. The City Plan Commission of Austin through its former Planning Supervisor, Mr. Glenn M. Dunkle, and through Mr. Charles Granger, Consultant to the Plan Commission gave encouragement to the pursuit of the present study and provided many of the street and topographic maps, aerial photographs and other information on existing and proposed railroad facilities. Without their help and consultation this study would have been most difficult. -

November/December 2017

Page 1 of 19 Travis Audubon Board, Staff, and Committees: Officers President: Frances Cerbins Vice President: Mark Wilson Treasurer: Carol Ray Secretary: Julia Marsden Directors: Advisory Council: Karen Bartoletti J. David Bamberger Shelia Hargis Valarie Bristol Clif Ladd Victor Emanuel Suzanne Kho Sam Fason Sharon Richardson Bryan Hale Susan Rieff Karen Huber Virginia Rose Mary Kelly Eric Stager Andrew Sansom Jo Wilson Carter Smith Office Staff: Executive Director: Joan Marshall Director of Administration & Membership: Jordan Price Land Manager and Educator: Christopher Murray Chaetura Canyon Stewards: Paul & Georgean Kyle Program Assistant: Nancy Sprehn Education Manager: Erin Cord Design Director & Website Producer: Nora Chovanec Committees: Baker Core Team: Clif Ladd and Chris Murray Blair Woods Management: Mark Wilson Commons Ford: Shelia Hargis and Ed Fair Chaetura Canyon Management: Paul and Georgean Kyle Education: Cindy Cannon Field Trip: Dennis Palafox Hornsby Bend: Eric Stager Outreach/Member Meetings: Jane Tillman and Cindy Sperry Youth: Virginia Rose and Mary Kay Sexton Page 2 of 19 Avian Ink Contest Winners Announced SEPTEMBER 1, 2017 It was a packed house at Blue Owl Brewery’s tasting room last Friday as we unveiled Golden Cheeked Wild Barrel, an experimental new beer celebrating the Golden-cheeked Warbler. The crowd raised their glasses to this inspiring tiny songbird, an endangered Texas native currently fighting for continued protection under the Endangered Species Act. In honor of all the birds that inspire our lives, the crowd also toasted the winners of the Avian Ink Tattoo Contest. Five tattoos were selected for their creative depictions of birds in ink. The 1st place winner received a $100 Gift Certificate to Shanghai Kate’s Tattoo Parlor. -

Civil War & Reconstruction in Austin

AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER ASSOCIATION AustinAustin Remembers.Remembers. “THE COLLECTIVE MEMORY OF AUSTIN & TRAVIS COUNTY” WINTER 2015 NEW EXHIBIT: DIVIDED CITY CIVIL WAR & RECONSTRUCTION IN AUSTIN BY MIKE MILLER May 2015 marks 150 years since the end of America’s Civil War. To mark the occasion, the Austin History Center has prepared a new exhibit in the Grand Hallway and Lobby: “Divided City: Civil War & Reconstruction in Austin.” The exhibit explores how this water- shed moment in American history affected our local community. Hundreds of photographs and original documents are on display to help visitors learn about and understand this period of our history and the legacy it left behind, a legacy that continues to influence our community today. On April 12, 1861, Confederate artillery bombarded Fort Sumter in South Carolina, signaling the beginning of the Civil War. The war would last four long, bloody years, nearly ripping the country apart. Southern states seceded from the United States to form the Confederate States of America, with Texas being the 7th state to join the Confederacy. The fight to leave the Union was predicated largely on the continuation and expansion of the institution of slavery, thereby protecting the southern economy and way of life. And yet the traditional “north vs. south” or “slavery vs. abolition” that we are often presented may be too simplistic an explanation for the realities that gripped this country. The road to the Civil War was more complex among its individual citizens. Not all southern- PICB 07051, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library. John Scott Pickle was one of the thousands of ers were secessionists; not all secessionists supported slavery; not all unionists opposed men who joined the Confederate Army. -

Local Texas Bridges

TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Environmental Affairs Division, Historical Studies Branch Historical Studies Report No. 2004-01 A Guide to the Research and Documentation of Local Texas Bridges By Lila Knight, Knight & Associates A Guide to the Research and Documentation of Local Texas Bridges January 2004 Revised October 2013 Submitted to Texas Department of Transportation Environmental Affairs Division, Historical Studies Branch Work Authorization 572-06-SH002 (2004) Work Authorization 572-02-SH001 (2013) Prepared by Lila Knight, Principal Investigator Knight & Associates PO Box 1990 Kyle, Texas 78640 A Guide to the Research and Documentation of Local Texas Bridges Copyright© 2004, 2013 by the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) All rights reserved. TxDOT owns all rights, title, and interest in and to all data and other information developed for this project. Brief passages from this publication may be reproduced without permission provided that credit is given to TxDOT and the author. Permission to reprint an entire chapter or section, photographs, illustrations and maps must be obtained in advance from the Supervisor of the Historical Studies Branch, Environmental Affairs Division, Texas Department of Transportation, 118 East Riverside Drive, Austin, Texas, 78704. Copies of this publication have been deposited with the Texas State Library in compliance with the State Depository requirements. For further information on this and other TxDOT historical publications, please contact: Texas Department of Transportation Environmental Affairs Division Historical Studies Branch Bruce Jensen, Supervisor Historical Studies Report No. 2004-01 By Lila Knight Knight & Associates Table of Contents Introduction to the Guide. 1 A Brief History of Bridges in Texas. 2 The Importance of Research. -

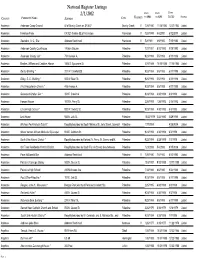

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE to SBR to NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE TO SBR TO NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY AndersonAnderson Camp Ground W of Brushy Creek on SR 837 Brushy Creek V7/25/1980 11/18/1982 12/27/1982 Listed AndersonFreeman Farm CR 323 3 miles SE of Frankston Frankston V7/24/1999 5/4/2000 6/12/2000 Listed AndersonSaunders, A. C., Site Address Restricted Frankston V5/2/1981 6/9/1982 7/15/1982 Listed AndersonAnderson County Courthouse 1 Public Square Palestine7/27/1991 8/12/1992 9/28/1992 Listed AndersonAnderson County Jail * 704 Avenue A. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonBroyles, William and Caroline, House 1305 S. Sycamore St. Palestine5/21/1988 10/10/1988 11/10/1988 Listed AndersonDenby Building * 201 W. Crawford St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonDilley, G. E., Building * 503 W. Main St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonFirst Presbyterian Church * 406 Avenue A Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonGatewood-Shelton Gin * 304 E. Crawford Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonHoward House 1011 N. Perry St. Palestine3/28/1992 1/26/1993 3/14/1993 Listed AndersonLincoln High School * 920 W. Swantz St. Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonLink House 925 N. Link St. Palestine10/23/1979 3/24/1980 5/29/1980 Listed AndersonMichaux Park Historic District * Roughly bounded by South Michaux St., Jolly Street, Crockett Palestine1/17/2004 4/28/2004 Listed AndersonMount Vernon African Methodist Episcopal 913 E. -

Historic Bridges in Texas

TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Environmental Affairs Division, Historical Studies Branch Historical Studies Report No. 2004-01 A Guide to the Research and Documentation of Historic Bridges in Texas By Lila Knight, Knight & Associates A Guide to the Research and Documentation of Historic Bridges in Texas January 2004 Prepared For Environmental Affairs Division Work Authorization 572-06-SH002 By Lila Knight Knight & Associates PO Box 1990 Kyle, Texas 78640 A Guide to the Research and Documentation of Historic Bridges in Texas Copyright © 2004 by the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) All rights reserved. TxDOT owns all rights, title, and interest in and to all data and other information developed for this project. Brief passages from this publication may be reproduced without permission provided that credit is given to TxDOT and the author. Permission to reprint an entire chapter or section, photographs, illustrations, and maps must be obtained in advance from the Supervisor of the Historical Studies Branch, Environmental Affairs Division, Texas Department of Transportation, 118 East Riverside Drive, Austin, Texas, 78704. Copies of this publication have been deposited with the Texas State Library in compliance with the State Depository requirements. For further information on this and other TxDOT historical publications, please contact: Texas Department of Transportation Environmental Affairs Division Historical Studies Branch Bruce Jensen, Supervisor Historical Studies Report No. 2004-01 By Lila Knight Knight & Associates Table of Contents Introduction Brief HI tory of Roads and Bridges In Texas Guide to Conducting R••earch on Texas Bridges Step One: Is the Bridge Listed in the National Register of Historic Places? Step Two: What is the Date of Construction? Step Three: What Type of Bridge is it? (Physical Description of the Bridge) Step Four: Why was the Bridge Constructed? (Function of the Bridge) Step Five: Why and How is this Bridge Important? (Historic Context) Step Six: Does the Bridge Retain its Historic Integrity? Overvle. -

Cover Page the Handle Holds

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/85166 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Mareite T.J.F. Title: Conditional freedom : free soil and fugitive slaves from the US South to Mexico's Northeast, 1803-1861 Issue Date: 2020-02-13 PART 2 * * * CRAFTING FREEDOM III Self-Liberated Slaves and Asylum in Northeastern Mexico, 1803-1836 Introduction During one of his several trips to Mexican Texas to promote black emigration from the US to Mexico, abolitionist Benjamin Lundy arrived at San Antonio de Bexar in August 1833 and recognized a “free black man” named Mathieu Thomas, whom he had met the previous summer in Nacogdoches. According to Lundy, the man was originally from North Carolina and had been brought to the region as a slave by his owner in the 1820s, but had been subsequently manumitted. Now employed as a blacksmith in Bexar, he appeared to be doing well for himself and he enthusiastically asserted that “the Mexicans pay him the same respect as to other laboring people”, regardless of the color of his skin. What Lundy was apparently not aware of was that Mathieu Thomas was in fact not a free black man at all, but rather a fugitive from slavery.1 His apparent success in Mexico (which neatly fit with Lundy’s goal of presenting Mexico as a racial haven), moreover, obscured a series of fierce struggles the blacksmith had had to overcome in order to secure his own freedom in the years before the Texas Revolution, as we will see. Countless fugitive slaves settled in the Mexican Northeast prior to Texan independence in 1836. -

FY 2012-13 City of Austin Approved Budget Vol II

2012 - 13 APPROVED BUDGET VOLUME II Table of Contents Department Budgets Internal Services Communications and Technology Management .................................... 1 Fleet Services ...................................................................................... 25 Support Services .................................................................................... 45 Building Services ................................................................................. 49 Communications and Public Information ............................................. 65 Contract Management ......................................................................... 79 Financial Services ................................................................................ 93 Government Relations ....................................................................... 119 Human Resources .............................................................................. 127 Law .................................................................................................... 145 Management Services ....................................................................... 163 Mayor and City Council ...................................................................... 185 Office of the City Auditor ................................................................... 189 Office of the City Clerk ....................................................................... 203 Office of Real Estate Services ........................................................... -

Street Fact Sheet FINAL

Mueller Street Legends Mueller’s dozens of new streets honor a diverse cross-section of Austin leaders and legends symbolizing the city’s great history and distinct culture. Here are the stories behind the names of Mueller’s first streets.* Aldrich Street Roy Wilkinson Aldrich Roy Aldrich served as a Texas Ranger from 1915 to 1947. His term of service at the time of his retirement was longer than that of any other Ranger. During his 32 years on the force, Mr. Aldrich became known in Texas academic circles for his interest in history and natural history. His collections of native flora and fauna and Texana found at his farm on Manor Road were famous throughout the state. The Aldrich farmland later became part of the Robert Mueller Municipal Airport and is today a part of Mueller. Antone Street Clifford Antone Clifford Antone was the founder of Antone’s, Austin’s Home of the Blues, bringing the blues and soul legends of the 1970s to what became one of the premier blues clubs in Texas. Later, Mr. Antone expanded his nightclub to establish Antone’s Records, recording both live shows and studio sets. Mr. Antone had begun working with several social and educational organizations creating the “Help Clifford Help Kids” fundraiser for American Youthworks and forming the “Neighbors in Need” benefit in response to Hurricane Katrina. He also taught music at both The University of Texas at Austin and Texas State University in San Marcos. Attra Street Tom Attra Tom Attra, state boxing legend, was named National Golden Gloves Champion in both 1942 and 1945. -

Dear Mr. Goode, Ms. Ogelsby and Mr. Rhodes, Attached Is a Letter

From: Martinez, Mike [Council Member] To: Rhodes, Willie Cc: Goode, Robert; Ott, Marc; Moore, Andrew; Garza, Bobby; Williamson, Laura Subject: FW: Code Enforcement Case, TRI Recycling, 3600 Lyons Rd. Date: Wednesday, December 30, 2009 11:08:25 AM Attachments: TRI-lttr to CoA.doc ATT2106267.htm Willie, Can we get an update on this issue ASAP. I have county Commissioner Eckhart also asking for updates as well. Thanks, Mike Mayor Pro Tem Mike Martinez 310 W. 2nd Street Austin, Texas 512.974.2264 From: nine francois [mailto: ] Sent: Tuesday, December 29, 2009 10:23 PM To: Goode, Robert; Pamela Ogelsby; Rhodes, Willie Cc: nine francois; Abe Zimmerman; Susana Almanza; Martinez, Mike [Council Member]; Morrison, Laura; corinne carson Subject: Fwd: Code Enforcement Case, TRI Recycling, 3600 Lyons Rd. Dear Mr. Goode, Ms. Ogelsby and Mr. Rhodes, Attached is a letter regarding the operation of TRI Recycling in our east Austin neighborhood. Please send me notice that you have received this e-mail. Thank you. Nine Francois, Co-Chair Govalle Neighborhood Association 512.391.1591 From: Martinez, Mike [Council Member] To: Curtis, Matt; Leffingwell, Lee; Shade, Randi; Spelman, William; Cole, Sheryl; Morrison, Laura; Riley, Chris Subject: RE: Update on Funeral Services for Mrs. Emma Barrientos Date: Tuesday, December 29, 2009 12:26:20 PM Thanks Matt Mayor Pro Tem Mike Martinez 310 W. 2nd Street Austin, Texas 512.974.2264 From: Curtis, Matt Sent: Tuesday, December 29, 2009 11:32 AM To: Martinez, Mike [Council Member]; Leffingwell, Lee; Shade, Randi; Spelman, William; Cole, Sheryl; Morrison, Laura; Riley, Chris Subject: Update on Funeral Services for Mrs. -

ETHJ Vol-39 No-1

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 39 Issue 1 Article 1 3-2001 ETHJ Vol-39 No-1 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation (2001) "ETHJ Vol-39 No-1," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 39 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol39/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME XXXIX 2001 NUMBER 1 HISTORICAL JOURNAL EAST TEXAS IDSTORICAL ASSOCIATION 2000-2001 OFFICERS Linda S. Hudson President Kenneth E. Hendrickson., Ir First Vice President 1Y ~on Second Vice President Portia L. Gordon Secretary-Treasurer DIRECTORS Janet G. Brandey Fouke. AR 2001 Kenneth Durham Longview 2001 Theresa McGintey ~ Houston 2001 Willie Earl TIndall San Augustine 2002 Donald Walker Lubbock 2002 Cary WlI1tz Houston 2002 R.G. Dean Nacogdoches 2oo3 Sarah Greene Gilmer 2003 Dan K. Utley Ptlugerville 2003 Donald Willett Galveston ex-President Patricia KeU BaylOWIl ex-President EDITORIAL BOARD ~~::o':;a:~~.~~:::~::~:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::~:~~::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::~~U:~ Garna L. Christian Houston Ouida Dean '" Nacogdocbes Patricia A. Gajda 1Yler Robert W. Glover F1int Bobby H. Johnson Nacogdochcs Patricia ](ell Baytown Max S. Late Fort Worth Chuck Parsons , Luling Fred Tarpley Commeree Archie P. McDonald EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AND EDITOR Mark D. Barringer ASSOCIATE EDITOR MEMBERSHIP INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERS pay $100 annually LIFE MEMBERS pay $300 or more BENEFAcrOR pays $100, PATRON pays $50 annually STUDENT MEMBERS pay $12 annually FAMILY MEMBERS pay $35 annually REGULAR MEMBERS pay $25 annually Journals $7.50 per copy P.O.