The Status and Distribution of Owls in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rediscovery, Biology, Vocalisations and Taxonomy of Fish Owls in Turkey

Rediscovery, biology, vocalisations and taxonomy of fish owls in Turkey Arnoud B van den Berg, Soner Bekir, Peter de Knijff & The Sound Approach n the Western Palearctic (WP) region, Brown Distribution and traditional taxonomy IFish Owl Bubo zeylonensis is one of the rarest Until recently, fish owls were grouped under the and least-known birds. The species’ range is huge, genus Ketupa. However, recent DNA research has from the Mediterranean east to Indochina, but it is shown that for reasons of paraphyly it is better to probably only in India and Sri Lanka that it is include this genus together with Scotopelia and regularly observed. In the 19th and 20th century, Nyctea in Bubo. Former Ketupa species, Brown a total of c 15 documented records became known Fish Owl, Tawny Fish Owl B flavipes and Buffy of the westernmost and palest taxon, semenowi, Fish Owl B ketupu cluster as close relatives of and no definite breeding was described for the Asian Bubo species like Spot-bellied Eagle-Owl WP. These records included just one for Turkey in B nipalensis and Barred Eagle-Owl B sumatranus the 20th century, in 1990. However, while the (König et al 1999, Sangster et al 2003, Knox 2008, species appears to be extinct in other WP coun- Wink et al 2008, Redactie Dutch Birding 2010). tries, several pairs have been found in southern Based on external morphology and geography, Turkey since 2004. New findings in 2009-10 cre- four subspecies of Brown Fish Owl are tradition- ated a rapid increase in our understanding of the ally recognized. -

Gtr Pnw343.Pdf

Abstract Marcot, Bruce G. 1995. Owls of old forests of the world. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW- GTR-343. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 64 p. A review of literature on habitat associations of owls of the world revealed that about 83 species of owls among 18 genera are known or suspected to be closely asso- ciated with old forests. Old forest is defined as old-growth or undisturbed forests, typically with dense canopies. The 83 owl species include 70 tropical and 13 tem- perate forms. Specific habitat associations have been studied for only 12 species (7 tropical and 5 temperate), whereas about 71 species (63 tropical and 8 temperate) remain mostly unstudied. Some 26 species (31 percent of all owls known or sus- pected to be associated with old forests in the tropics) are entirely or mostly restricted to tropical islands. Threats to old-forest owls, particularly the island forms, include conversion of old upland forests, use of pesticides, loss of riparian gallery forests, and loss of trees with cavities for nests or roosts. Conservation of old-forest owls should include (1) studies and inventories of habitat associations, particularly for little-studied tropical and insular species; (2) protection of specific, existing temperate and tropical old-forest tracts; and (3) studies to determine if reforestation and vege- tation manipulation can restore or maintain habitat conditions. An appendix describes vocalizations of all species of Strix and the related genus Ciccaba. Keywords: Owls, old growth, old-growth forest, late-successional forests, spotted owl, owl calls, owl conservation, tropical forests, literature review. -

Tc & Forward & Owls-I-IX

USDA Forest Service 1997 General Technical Report NC-190 Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere Second International Symposium February 5-9, 1997 Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Editors: James R. Duncan, Zoologist, Manitoba Conservation Data Centre Wildlife Branch, Manitoba Department of Natural Resources Box 24, 200 Saulteaux Crescent Winnipeg, MB CANADA R3J 3W3 <[email protected]> David H. Johnson, Wildlife Ecologist Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 600 Capitol Way North Olympia, WA, USA 98501-1091 <[email protected]> Thomas H. Nicholls, retired formerly Project Leader and Research Plant Pathologist and Wildlife Biologist USDA Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station 1992 Folwell Avenue St. Paul, MN, USA 55108-6148 <[email protected]> I 2nd Owl Symposium SPONSORS: (Listing of all symposium and publication sponsors, e.g., those donating $$) 1987 International Owl Symposium Fund; Jack Israel Schrieber Memorial Trust c/o Zoological Society of Manitoba; Lady Grayl Fund; Manitoba Hydro; Manitoba Natural Resources; Manitoba Naturalists Society; Manitoba Critical Wildlife Habitat Program; Metro Propane Ltd.; Pine Falls Paper Company; Raptor Research Foundation; Raptor Education Group, Inc.; Raptor Research Center of Boise State University, Boise, Idaho; Repap Manitoba; Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada; USDI Bureau of Land Management; USDI Fish and Wildlife Service; USDA Forest Service, including the North Central Forest Experiment Station; Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife; The Wildlife Society - Washington Chapter; Wildlife Habitat Canada; Robert Bateman; Lawrence Blus; Nancy Claflin; Richard Clark; James Duncan; Bob Gehlert; Marge Gibson; Mary Houston; Stuart Houston; Edgar Jones; Katherine McKeever; Robert Nero; Glenn Proudfoot; Catherine Rich; Spencer Sealy; Mark Sobchuk; Tom Sproat; Peter Stacey; and Catherine Thexton. -

About Owls By: AV

All About Owls By: AV 1 Contents 1. Say Hi To Owls_________________________ p. 3 2. Body Parts_____________________________ p. 4-5 3. Getting Hungry__________________________ p.6-7 4. So Many Owls__________________________ p.8-11 5. Where Are They_________________________ p. 12 6. Got To Go, Bye__________________________ p. 13 7. Quiz Zone______________________________ p. 14 8. About The Author________________________ p. 15 9. Glossary_______________________________ p. 16 10. References___________________________ p.17 2 Say Hi To Owls Swoosh! The great grey owl soares overhead seeking for some food. Then swoosh the owl spots a little mouse crawling through the grass and strikes at it. In this book I will teach you all about owls. If you don’t know what an owl is then this book will be good for you. In this book you will learn about their body parts, what they eat, and the types of owls. I hope you enjoy this book. 3 Body Parts Owls have way more body parts than you think. If you look to the right you will see a picture of all their body parts. But some of their most important body parts are their eyes witch help them see in the dark, their huge ears which help them hear very well, and their flexible necks. 4 Great Big Eyes Huge ears Owls have big eyes. For example, if you Owls have huge ears. Teacher fox says, open your mouth into an O shape that is the “if you lift up the feathers you can see the size of an owls eye. Owls can use those eyes back of their eyes through the ear.” That is to see in the dark. -

Buffy Fish Owl Ketupa Ketupu Breeding in Sundarbans Tiger Reserve, India Manoj Sharma, Soma Jha & Atul Jain

SHARMA ET. AL.: Buffy Fish Owl 27 Photos: Praveen ES 26. Short-tailed Shearwater in flight. 27. Wedge-tailed Shearwater. Though it is considered to be a vagrant in India, there are of these birds. We are grateful to Nameer P. O., College of Forestry, Kerala Agricultural reports of regular sightings of these birds off the western coasts University, for his support, and Social Forestry, Kerala Forest Department, for organising of the Malayan peninsula (Giri et al. 2013). This sighting from the trip. We wish to thank participants from the College of Forestry, Kerala Agricultural the Arabian Sea, first off the Kerala coast, together with the ones University; Sree Sankaracharya University, Kalady; Kerala Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Pookode; and Kerala Forest Research Institute, Peechi. mentioned earlier, suggests that some birds drift off from their normal course of migration, in the western Pacific, to cross the Indian Ocean during their spring migration. References On our return journey we photographed a Wedge-tailed BirdLife International. 2014. BirdLife International Species factsheet: Puffinus tenuirostris. Shearwater A. pacifica [27], which had been earlier recorded Website: http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/home. [Accessed on 10 June 2014.] from the seas off Kannur, in Kerala, in May 2011(Praveen et al. Giri, P., Dey, A., & Sen, S. K., 2013. Short-tailed Shearwater Ardenna tenuirostris from 2013). This is the second photographic record of this species Namkhana, West Bengal: A first record for India. Indian BIRDS 8 (5): 131. from India. Praveen J., Jayapal, R., Pittie, A., 2013. Notes on Indian rarities—1: Seabirds. Indian BIRDS 8 (5): 113–125. -

OWLS and COYOTES

AT HOME WITH NATURE: eLearning Resource | Suggested for: general audiences, families OWLS and COYOTES The Eastern Coyote The Eastern coyote, common to the Greater Toronto Area, is a hybrid between the Western coyote and Eastern wolf. Adults typically weigh between 10–22 kg, but thick fur makes them appear bigger. They have grey and reddish-brown fur, lighter underparts, a pointed nose with a red-brown top, a grey patch between the eyes, and a bushy, black-tipped tail. Coyote ears are more triangular than a wolf’s. Coyotes are not pack animals, but a mother will stay with her young until they are about one year old. Coyotes communicate with a range of sounds including yaps, whines, barks, and howls. Habitat Eastern coyotes are very adaptable and can survive in both rural and urban habitats. They often build their dens in old woodchuck holes, which they expand to about 30 cm in diameter and about 3 m in depth. Although less common, coyotes also build dens in hollow trees. Diet What is on the menu for coyotes? Check off each food type. Squirrels Frogs Grasshoppers Dog kibble Berries Rats Humans Food compost Garden vegetables Snakes Small birds Deer If you selected everything, except for humans, you are correct! Coyotes are opportunistic feeders that consume a variety of foods including fallen fruit, seeds, crops, and where they can find it pet food and compost. However, their diet is comprised mainly of insects, reptiles, amphibians, and small mammals. Their natural rodent control is beneficial to city dwellers and farmers alike. Preying on small mammals does mean though that our pets are on the menu, so it is important to keep them on leash close to you. -

Owls.1. Newton, I. 2002. Population Limitation in Holarctic Owls. Pp. 3-29

Owls.1. Newton, I. 2002. Population limitation in Holarctic Owls. Pp. 3-29 in ‘Ecology and conservation of owls’, ed. I. Newton, R. Kavenagh, J. Olsen & I. Taylor. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia. POPULATION LIMITATION IN HOLARCTIC OWLS IAN NEWTON Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Monks Wood, Abbots Ripton, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire PE28 2LS, United Kingdom. This paper presents an appraisal of research findings on the population dynamics, reproduction and survival of those Holarctic Owl species that feed on cyclically-fluctuating rodents or lagomorphs. In many regions, voles and lemmings fluctuate on an approximate 3–5 year cycle, but peaks occur in different years in different regions, whereas Snowshoe Hares Lepus americanus fluctuate on an approximate 10-year cycle, but peaks tend to be synchronised across the whole of boreal North America. Owls show two main responses to fluctuations in their prey supply. Resident species stay on their territories continuously, but turn to alternative prey when rodents (or lagomorphs) are scarce. They survive and breed less well in low than high rodent (or lagomorph) years. This produces a lag in response, so that years of high owl densities follow years of high prey densities (examples: Barn Owl Tyto alba, Tawny Owl Strix aluco, Ural Owl S. uralensis). In contrast, preyspecific nomadic species can breed in different areas in different years, wherever prey are plentiful. They thus respond more or less immediately by movement to change in prey-supply, so that their local densities can match the local food-supply at the time, with minimum lag (examples: Short-eared Owl: Asio flammeus, Long-eared Owl A. -

Systematics of Smaller Asian Night Birds Based on Voice

SYSTEMATICS OF SMALLER ASIAN NIGHT BIRDS BASED ON VOICE BY JOE T. MARSHALL ORNITHOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS NO. 25 PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION 1978 SYSTEMATICS OF SMALLER ASIAN NIGHT BIRDS BASED ON VOICE BY JOE T. MARSHALL ORNITHOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS NO. 25 PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION 1978 Frontispiece: Otus icterorhynchus?stresemanni of Sumatra, with apologiesto G. M. Sutton and The Birdsof Arizona. The absenceof wings,far from implyingflightlessness, emphasizes the important parts of the plumagefor speciescomparisons--the interscapulars and flanks. These "control" the more variablepatterns of head and wings,which will always be in harmonywith the basicpattern of back and flanks. ORNITHOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS This series, publishedby the American Ornithologists'Union, has been estab- lished for major papers too long for inclusionin the Union's journal, The Auk. Publication has been subsidizedby funds from the National Fish and Wildlife Laboratory, Washington, D.C. Correspondenceconcerning manuscripts for publicationin this seriesshould be addressedto the Editor-elect, Dr. Mercedes S. Foster, Department of Biology, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620. Copiesof OrnithologicalMonographs may be orderedfrom the Assistantto the Treasurer of the AOU, Glen E. Woolfenden,Department of Biology, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620. (See price list on back and inside back cover.) OrnithologicalMonographs No. 25, viii + 58 pp., separatephonodisc supple- ment. Editor, John William Hardy Special Associate Editors of this issue, Kenneth C. Parkes, Section of Birds, Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania15213, and Oliver L. Austin, Jr., Departmentof Natural Sciences,Florida State Museum, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611. Assistant Editor, June B. Gabaldon Author, Joe T. Marshall, Bird Section, National Fish and Wildlife Laboratory, National Museumof Natural History, Washington,D.C. -

SOUTHERN INDIA and SRI LANKA

Sri Lanka Woodpigeon (all photos by D.Farrow unless otherwise stated) SOUTHERN INDIA and SRI LANKA (WITH ANDAMANS ISLANDS EXTENSION) 25 OCTOBER – 19 NOVEMBER 2016 LEADER: DAVE FARROW This years’ tour to Southern India and Sri Lanka was once again a very successful and enjoyable affair. A wonderful suite of endemics were seen, beginning with our extension to the Andaman Islands where we were able to find 20 of the 21 endemics, with Andaman Scops and Walden’s Scops Owls, Andaman and Hume’s Hawk Owls leading the way, Andaman Woodpigeon and Andaman Cuckoo Dove, good looks at 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: South India and Sri Lanka 2016 www.birdquest-tours.com Andaman Crake, plus all the others with the title ‘Andaman’ (with the exception of the Barn Owl) and a rich suite of other birds such as Ruddy Kingfisher, Oriental Pratincole, Long-toed Stint, Long-tailed Parakeets and Mangrove Whistler. In Southern India we birded our way from the Nilgiri Hills to the lowland forest of Kerala finding Painted and Jungle Bush Quail, Jungle Nightjar, White-naped and Heart-spotted Woodpeckers, Malabar Flameback, Malabar Trogons, Malabar Barbet, Blue-winged Parakeet, Grey-fronted Green Pigeons, Nilgiri Woodpigeon, Indian Pitta (with ten seen on the tour overall), Jerdon's Bushlarks, Malabar Larks, Malabar Woodshrike and Malabar Whistling Thrush, Black-headed Cuckooshrike, Black-and- Orange, Nilgiri, Brown-breasted and Rusty-tailed Flycatchers, Nilgiri and White-bellied Blue Robin, Black- chinned and Kerala Laughingthrushes, Dark-fronted Babblers, Indian Rufous Babblers, Western Crowned Warbler, Indian Yellow Tit, Indian Blackbird, Hill Swallow, Nilgiri Pipit, White-bellied Minivet, the scarce Yellow-throated and Grey-headed Bulbuls, Flame-throated and Yellow-browed Bulbuls, Nilgiri Flowerpecker, Loten's Sunbird, Black-throated Munias and the stunning endemic White-bellied Treepie. -

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

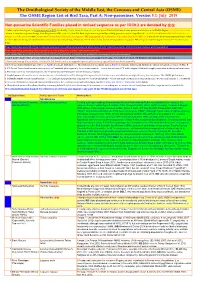

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

Journal of Threatened Taxa

PLATINUM The Journal of Threatened Taxa (JoTT) is dedicated to building evidence for conservaton globally by publishing peer-reviewed artcles OPEN ACCESS online every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All artcles published in JoTT are registered under Creatve Commons Atributon 4.0 Internatonal License unless otherwise mentoned. JoTT allows unrestricted use, reproducton, and distributon of artcles in any medium by providing adequate credit to the author(s) and the source of publicaton. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservaton globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Note Tawny Fish-owl Ketupa flavipes Hodgson, 1836 (Aves: Strigiformes: Strigidae): recent record from Arunachal Pradesh, India Malyasri Bhatacharya, Bhupendra S. Adhikari & G.V. Gopi 26 February 2021 | Vol. 13 | No. 2 | Pages: 17837–17840 DOI: 10.11609/jot.5382.13.2.17837-17840 For Focus, Scope, Aims, Policies, and Guidelines visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-0 For Artcle Submission Guidelines, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions#onlineSubmissions For Policies against Scientfc Misconduct, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-2 For reprints, contact <[email protected]> The opinions expressed by the authors do not refect the views of the Journal of Threatened Taxa, Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society, Zoo Outreach Organizaton, or any of the partners. The journal, -

Red List of Bangladesh 2015

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary Chief National Technical Expert Mohammad Ali Reza Khan Technical Coordinator Mohammad Shahad Mahabub Chowdhury IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Bangladesh Country Office 2015 i The designation of geographical entitles in this book and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature concerning the legal status of any country, territory, administration, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The biodiversity database and views expressed in this publication are not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Bangladesh Forest Department and The World Bank. This publication has been made possible because of the funding received from The World Bank through Bangladesh Forest Department to implement the subproject entitled ‘Updating Species Red List of Bangladesh’ under the ‘Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection (SRCWP)’ Project. Published by: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office Copyright: © 2015 Bangladesh Forest Department and IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holders. Citation: Of this volume IUCN Bangladesh. 2015. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, pp. xvi+122. ISBN: 978-984-34-0733-7 Publication Assistant: Sheikh Asaduzzaman Design and Printed by: Progressive Printers Pvt.