Atlanta Braves Clippings Friday, September 25, 2020 Braves.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richmond Flying Squirrels (43-44) Vs. Bowie Baysox (51-34) RHP Matt Frisbee (5-1, 1.29) Vs

Richmond Flying Squirrels | 3001 N Arthur Ashe Blvd., Richmond, VA 23230 | 804-359-3866 | SquirrelsBaseball.com | @GoSquirrels Richmond Flying Squirrels (43-44) vs. Bowie Baysox (51-34) RHP Matt Frisbee (5-1, 1.29) vs. RHP Blaine Knight (3-3, 4.07) RHP Akeel Morris (2-0, 7.45) vs. RHP Cody Sedlock (5-2, 4.01) Saturday, August 14, 2021 | Games #88/89 | Road Games #42/43 7:05 p.m. | Prince George’s Stadium | Bowie, Md. UPCOMING GAMES & PROBABLE PITCHERS Sun., August 15 at Bowie 1:35 p.m. RHP Trenton Toplikar (2-6, 4.90) vs. RHP Gray Fenter (4-2, 6.75) Mon., August 16 OFF DAY Tues., August 17 Erie 6:35 p.m. TBD vs. RHP Aaron Blair (0-2, 4.15) Wed., August 18 Erie 6:35 p.m. TBD vs. LHP Michael Plassmeyer (1-6, 4.42) THURSDAY: The Flying Squirrels fell to the Bowie Baysox, 8-6. Bowie jumped ahead, 2-0, in the first with back-to-back homers by Seth Mejias-Brean and Kyle Stowers. Richmond tied the game in the fourth with a two-run double by Jacob Heyward. In the 2021 FLYING SQUIRRELS fifth, Diego Rincones hit a two-run homer to put the Flying Squirrels ahead, 4-2. In the bottom of the fifth, Cadyn Grenier hit a Overall Record ..............................43-44 solo homer and Zach Watson gave the Baysox a 5-4 lead with a two-run double. Bowie pulled away with three runs in the sixth inning. The Flying Squirrels closed the score to 8-6 with a two-run homer by David Villar in the top of the seventh. -

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings November 21, 2012

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings November 21, 2012 CINCINNATI ENQUIRER Pitching is pricey, transactions By John Fay | 11/20/2012 12:17 PM ET Want to know why the Reds would be wise to lock up Homer Bailey and Mat Latos long-term? The Kansas City Royals agreed to a three-year deal with Jeremy Guthrie that pays him $5 million on 2013, $11 million in 2014 and $9 million in 2015. He went 8-12 with a 4.76 ERA and 1.41 WHIP. Bailey went 13-10 with a 3.68 ERA and a 1.24 WHIP. Latos went 14-4 with a 2.48 ERA and a 1.16 WHIP. It’s a bit apples and oranges: Guthrie is a free agent; Bailey is arbitration-eligible for the second time, Latos for the first. But the point is starting pitching — even mediocre starting pitching — is expensive. SIX ADDED: The Reds added right-handers Carlos Contreras, Daniel Corcino, Curtis Partch and Josh Ravin, left-hander Ismael Guillon and outfielder Yorman Rodriguez to the roster in order to protect them from the Rule 5 draft. Report: Former Red Frank Pastore badly hurt in motorcycle wreck By dclark | 11/20/2012 7:55 PM ET The Inland Valley Daily Bulletin is reporting that former Cincinnati Reds pitcher Frank Pastore, a Christian radio personality in California, was badly injured Monday night after being thrown from his motorcycle onto the highway near Duarte, Calif. From dailybulletin.com’s Juliette Funes: A 55-year-old motorcyclist from Upland was taken to a trauma center when his motorcycle was hit by a car on the 210 Freeway Monday night. -

A's News Clips, Saturday, April 21, 2012 Oakland A's Fall To

A’s News Clips, Saturday, April 21, 2012 Oakland A's fall to Cleveland Indians 4-3 By Carl Steward, Oakland Tribune Yoenis Cespedes had a major league first Friday night with his first three-hit game. Alas, according to A's starter Graham Godfrey, he also had a first -- the worst control game of his life. "That may have been the most walks I've ever given up in a game," Godfrey said after he issued five bases on balls and hit two batters in the A's 4-3 loss to the Cleveland Indians before 14,340 fans at the Oakland Coliseum. Godfrey (0-3) gave up all four Indians runs, and three of those runs were a result of batters he either walked or hit. What was particularly frustrating was that he said he had good stuff but just couldn't command it. "Everything felt great, and I made a lot of good pitches that ended up not being called a strike," he said. "I'm a control guy, and that's very uncharacteristic of me. There's something not right, but I still have a lot of confidence in my stuff and I'm looking forward to my next outing." To wit, Godfrey walked just five batters in 25 innings in 2011 with the A's (five appearances, four starts). "He got behind some guys and he's done that a little bit in the past, but he seems to be able to recover," manager Bob Melvin said. "It didn't get out of hand tonight, but it was not his best effort." Former Oakland third baseman Jack Hannahan drove in three of the Indians' runs with a second-inning sacrifice fly and a two-run double in the fourth. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Cincinnati Reds' Eugenio Suarez Celebrates After Hitting a Solo Home Run Off San Diego Padres Relief Pitcher Brad Hand in the Seventh Inning Thursday, Aug

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings August 24, 2017 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1990-The Reds release Ken Griffey, Sr. MLB.COM 'Tokki 2' belts 33rd homer as Reds fall to Cubs By Mark Sheldon and Andrew Call / MLB.com | 12:05 AM ET + 196 COMMENTS CINCINNATI -- The Cubs are playing the right teams at the right time to enable them to pull away in the National League Central division race. A 9-3 victory over the Reds on Wednesday night -- aided by a three-run first inning and five-run fourth -- was their fifth win in a row. "Collectively, we were all going through a down period [in the first half of the season]," infielder Tommy La Stella said. "The talent has always been there. It's starting to turn for us right now, and turn at the right time." With the Brewers' 4-2 loss to the Giants, the Cubs opened a season-high 3 1/2-game lead in the division. In the midst of playing 13 straight games against last-place teams -- the Blue Jays, Reds and Phillies -- Chicago has won seven of the first nine games. For the season series, the Cubs have also won 10 of 15 games vs. the Reds. "You can struggle in the second half or you can learn from your mistakes and get better," winning pitcher Mike Montgomery said after the Cubs moved 11 games over .500 for the first time this season. "Now it's all about getting into the playoffs. We're completely over last year." Reds starter Asher Wojciechowski had a wobbly outing from the get-go as he faced eight batters -- and walked three -- in a 35-pitch first inning and allowed three runs. -

2016 Topps Opening Day Baseball Checklist

BASE OD-1 Mike Trout Angels® OD-2 Noah Syndergaard New York Mets® OD-3 Carlos Santana Cleveland Indians® OD-4 Derek Norris San Diego Padres™ OD-5 Kenley Jansen Los Angeles Dodgers® OD-6 Luke Jackson Texas Rangers® Rookie OD-7 Brian Johnson Boston Red Sox® Rookie OD-8 Russell Martin Toronto Blue Jays® OD-9 Rick Porcello Boston Red Sox® OD-10 Felix Hernandez Seattle Mariners™ OD-11 Danny Salazar Cleveland Indians® OD-12 Dellin Betances New York Yankees® OD-13 Rob Refsnyder New York Yankees® Rookie OD-14 James Shields San Diego Padres™ OD-15 Brandon Crawford San Francisco Giants® OD-16 Tom Murphy Colorado Rockies™ Rookie OD-17 Kris Bryant Chicago Cubs® OD-18 Richie Shaffer Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie OD-19 Brandon Belt San Francisco Giants® OD-20 Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® OD-21 Mike Moustakas Kansas City Royals® OD-22 Roberto Osuna Toronto Blue Jays® OD-23 Jimmy Nelson Milwaukee Brewers™ OD-24 Luis Severino New York Yankees® Rookie OD-25 Justin Verlander Detroit Tigers® OD-26 Ryan Braun Milwaukee Brewers™ OD-27 Chris Tillman Baltimore Orioles® OD-28 Alex Rodriguez New York Yankees® OD-29 Ichiro Miami Marlins® OD-30 R.A. Dickey Toronto Blue Jays® OD-31 Alex Gordon Kansas City Royals® OD-32 Raul Mondesi Kansas City Royals® Rookie OD-33 Josh Reddick Oakland Athletics™ OD-34 Wilson Ramos Washington Nationals® OD-35 Julio Teheran Atlanta Braves™ OD-36 Colin Rea San Diego Padres™ Rookie OD-37 Stephen Vogt Oakland Athletics™ OD-38 Jon Gray Colorado Rockies™ Rookie OD-39 DJ LeMahieu Colorado Rockies™ OD-40 Michael Taylor Washington Nationals® OD-41 Ketel Marte Seattle Mariners™ Rookie OD-42 Albert Pujols Angels® OD-43 Max Kepler Minnesota Twins® Rookie OD-44 Lorenzo Cain Kansas City Royals® OD-45 Carlos Beltran New York Yankees® OD-46 Carl Edwards Jr. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Monday, August 21, 2017 * The Boston Globe The pick here is Andrew Benintendi over Aaron Judge Dan Shaughnessy Aaron Judge vs. Andrew Benintendi. Forget 2017 American League Rookie of the Year. I’m asking . which guy would you rather have on your team for the next 15 seasons? We love these Yankee-Red Sox mano-a-manos. It’s as old as the rivalry itself. Joe DiMagggio came to the bigs in 1936. Ted Williams burst on the scene three years later. Throughout the 1940s, it was a raging argument. We were even led to believe that the respective owners of the Sox and Yankees once made a late-night swap while in a drunken haze. The alleged trade was called off by dawn’s early light. Remember when the Sox had Carlton Fisk and the Yanks had Thurman Munson? New York’s grumpy catcher was a league MVP before his career was tragically cut short when he crashed his plane in 1979. Fisk went on to become a Hall of Famer. Don Mattingly and Wade Boggs were rivals of sorts in the 1980s and who can forget those early years of this new century when Nomar Garciaparra vs. Derek Jeter was a real debate. Now we have Judge and Benintendi. Big Poison and Little Poison. It’s 6 feet 7 inches and 282 pounds vs. 5-10 and 170. It’s not about Rookie of the Year anymore. Even though he is playing as badly as anyone can play at the moment, Judge pretty much retired the rookie trophy with his ridiculous first half. -

Chicago White Sox 2018 Game Notes and Information

CHICAGO WHITE SOX 2018 GAME NOTES AND INFORMATION Chicago White Sox Media Relations Department 333 W. 35th Street Chicago, IL 60616 Phone: 312-674-5300 Senior Director: Bob Beghtol Assistant Director: Ray Garcia Manager: Billy Russo Coordinators: Joe Roti and Hannah Sundwall © 2018 Chicago White Sox whitesox.com loswhitesox.com whitesoxpressbox.com chisoxpressbox.com @whitesox WHITE SOX 2018 BREAKDOWN CHICAGO WHITE SOX (52-79) at NEW YORK YANKEES (83-48) Sox After 131 | 132 in 2017 ..........52-79 | 52-80 Streak ......................................................Won 4 RHP James Shields (5-15, 4.59) vs. RHP Lance Lynn (8-9, 4.84) Current Trip...................................................4-1 Game #132 | Road #67 Tuesday, August 28 6:05 p.m. CT Yankee Stadium Last Homestand ...........................................3-2 Last 10 Games .............................................7-3 NBCSCH WGN 720-AM NBCSportsChicago.com MLB.TV Series Record ........................................12-24-7 Series First Game.....................................15-29 WHITE SOX AT A GLANCE WHITE SOX VS. NEW YORK-AL First | Second Half ........................33-62 | 19-17 Home | Road ................................25-40 | 27-39 The Chicago White Sox have won a season-high tying four The Yankees lead the season series, 3-1, including a three- Day | Night ....................................19-39 | 33-40 straight games, 10 of their last 13 and 15 of 24 as they continue game sweep from 8/6-8 (fi rst in Chicago since 5/27-29/02). Opp. At-Above | Below .500 .........20-40 | 32-39 a seven-game trip tonight at Yankee Stadium. The Sox are batting .197/.250/.299 (29-147) with a 4.50 ERA vs. RHS | LHS .............................. 41-58 | 11-21 RHP James Shields is scheduled to start for the White Sox, (20 ER/40.0 IP) and have been outscored, 20-12. -

Atlanta Braves Clippings Wednesday, May 6, 2020 Braves.Com

Atlanta Braves Clippings Wednesday, May 6, 2020 Braves.com Braves' Top 5 center fielders: Bowman's take By Mark Bowman No one loves a good debate quite like baseball fans, and with that in mind, we asked each of our beat reporters to rank the top five players by position in the history of their franchise, based on their career while playing for that club. These rankings are for fun and debate purposes only … if you don’t agree with the order, participate in the Twitter poll to vote for your favorite at this position. Here is Mark Bowman’s ranking of the top 5 center fielders in Braves history. Next week: Right fielders. 1. Andruw Jones, 1996-2007 Key fact: Stands with Roberto Clemente, Willie Mays and Ichiro Suzuki as the only outfielders to win 10 consecutive Gold Glove Awards The 60.9 bWAR (Baseball Reference’s WAR model) Andruw Jones produced during his 11 full seasons (1997-2007) with Atlanta ranked third in the Majors, trailing only Alex Rodriguez (85.7) and Barry Bonds (79.2). Chipper Jones was fourth at 58.9. Within this span, the Braves center fielder led all Major Leaguers with a 26.7 Defensive bWAR. Hall of Fame catcher Ivan Rodriguez ranked second with 16.5. The next closest outfielder was Mike Cameron (9.6). Along with establishing himself as one of the greatest defensive outfielders baseball has ever seen during his time with Atlanta, Jones became one of the best power hitters in Braves history. He ranks fourth in franchise history with 368 homers, and he set the club’s single-season record with 51 homers in 2005. -

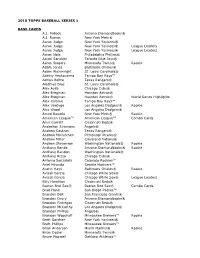

2018 Topps Series 1 Checklist Finala

2018 TOPPS BASEBALL SERIES 1 BASE CARDS A.J. Pollock Arizona Diamondbacks® A.J. Ramos New York Mets® Aaron Judge New York Yankees® Aaron Judge New York Yankees® League Leaders Aaron Judge New York Yankees® League Leaders Aaron Nola Philadelphia Phillies® Aaron Sanchez Toronto Blue Jays® Aaron Slegers Minnesota Twins® Rookie Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® Adam Wainwright St. Louis Cardinals® Adeiny Hechavarria Tampa Bay Rays™ Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® Aledmys Diaz St. Louis Cardinals® Alex Avila Chicago Cubs® Alex Bregman Houston Astros® Alex Bregman Houston Astros® World Series Highlights Alex Colome Tampa Bay Rays™ Alex Verdugo Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie Alex Wood Los Angeles Dodgers® Amed Rosario New York Mets® Rookie American League™ American League™ Combo Cards Amir Garrett Cincinnati Reds® Andrelton Simmons Angels® Andrew Cashner Texas Rangers® Andrew McCutchen Pittsburgh Pirates® Andrew Miller Cleveland Indians® Andrew Stevenson Washington Nationals® Rookie Anthony Banda Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie Anthony Rendon Washington Nationals® Anthony Rizzo Chicago Cubs® Antonio Senzatela Colorado Rockies™ Ariel Miranda Seattle Mariners™ Austin Hays Baltimore Orioles® Rookie Avisail Garcia Chicago White Sox® Avisail Garcia Chicago White Sox® League Leaders Billy Hamilton Cincinnati Reds® Boston Red Sox® Boston Red Sox® Combo Cards Brad Hand San Diego Padres™ Brandon Belt San Francisco Giants® Brandon Drury Arizona Diamondbacks® Brandon Finnegan Cincinnati Reds® Brandon McCarthy Los Angeles Dodgers® Brandon Phillips Angels® Brandon Woodruff -

Clips for 7-12-10

MEDIA CLIPS – Oct. 29, 2018 Rockies decline Parra's option for 2019 Do-Hyoung Park | MLB.com | Oct. 30th, 2018 The Rockies have declined a $12 million club option on outfielder Gerardo Parra for the 2019 season, exercising a $1.5 million buyout on Tuesday to make him a free agent. Parra appeared in 142 games in 2018 but started only 97 of them as a platoon outfielder, primarily in left field. He hit .284/.342/.372 in the final year of a three-year, $27.5 million contract inked prior to the 2016 season. The two-time National League Gold Glove Award winner lost playing time toward the end of the regular season when David Dahl returned from injury and Matt Holliday made his return to Colorado in August. The left-handed-hitting Parra, 31, struggled to live up to expectations in his first year with Colorado in 2016, hitting .253 with a .671 OPS, but he rebounded in '17 with career highs in average (.309) and RBIs (71). He spent the first five-plus seasons of his 10-year career with the D-backs before brief stints with Milwaukee and Baltimore prior to his arrival in Denver. Still, the Rockies will entertain the idea of agreeing to a less expensive deal with Parra, who showed value as a pinch- hitter this season by batting .393/.433/.536 with one homer, one double and two walks in 30 plate appearances. Franchise mainstay Carlos Gonzalez and Holliday are also free agents again for the Rockies. Colorado has two starting outfield positions locked up for 2019 between Dahl and three-time All-Star Charlie Blackmon, who in April was extended through the '21 season with player options for '22 and '23. -

2019 National Sports and Entertainment History Bee Round 2

Sports and Entertainment Bee 2018-2019 Prelims 2 Prelims 2 Regulation (Tossup 1) This man stars in an oft-parodied commercial in which he states \Ballgame" before taking a drink of Gatorade Flow. In 2017, this man's newly acquired teammate told him \they say I gotta come off the bench." This man missed nearly the entire 2014-2015 season after suffering a horrific leg injury while practicing for the US National Team. Sam Presti sent Domantas Sabonis and Victor Oladipo to the Indiana Pacers in exchange for this player, who then surprisingly didn't bolt to the Lakers in the 2018 off-season. For the point, name this player who formed an unsuccessful \Big Three" with Carmelo Anthony and Russell Westbrook on the Oklahoma City Thunder. ANSWER: Paul Clifton Anthony George (accept PG13) (Tossup 2) This series used Ratatat's \Cream on Chrome" as background music for many early episodes. Side projects of this series include a \Bedtime" version featuring literature readings and an educational \Basics" version. This series' 2019 April Fools' Day gag involved the a 4Kids dub of Pokemon claiming that Brock loved jelly donuts. This series celebrated million-subscriber benchmarks with episodes featuring the Taco Town 15-layer taco and the Every-Meat Burrito and Death Sandwich from Regular Show. For the point, name this YouTube channel starring Andrew Rea, who cooks various foods as inspired by popular culture. ANSWER: Binging with Babish (Tossup 3) The creators of this game recently announced a \Royal" edition which will add a third semester of gameplay. In April 2019, a heavily criticzed Kotaku article claimed that this game's theme song, \Wake up, Get up, Get out there," contains a slur against people with learning disabilities.